“Hanging one scoundrel, it appears, does not deter the next. Well, what of it? The first one is at least disposed of.”

— H.L. Mencken (1880-1956)

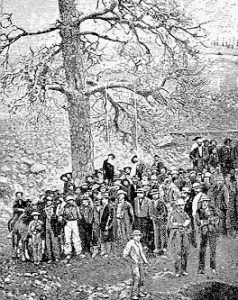

Execution by hanging was the most popular legal and extralegal form of putting criminals to death in the United States. Brought over to the States from our English ancestors, the method originated in Persia (now Iran) about 2,500 years ago. Hanging soon became the method of choice for most countries, as it produced an obvious deterrent by a simple method. It also made a good public spectacle, considered necessary during those times, as viewers looked above them to the gallows or trees to watch the punishment. Legal hangings, practiced by the early American colonists, were readily accepted by the public as a proper punishment for serious crimes like theft, rape, and murder. It was also readily practiced for activities not considered crimes today, such as witchcraft, sodomy, and concealing a birth.

For centuries, most hangings were carried out by the sheriff or legal entity of the town or county where the death sentence had been passed. Prisoner’s deaths were usually painful as most executioners were not proficient enough to calculate the correct “drop” of the hangman’s noose to ensure breaking the neck. Thus, the victim usually dies by strangulation. Using gallows with a trap door did not become common until the 1870s. Before that, most were hanged from a tree branch, turned off the back of a cart, or from a horse.

Hangings began in the U.S. when settlements started to be formed in the “New World.” One of the first was John Billington, who arrived with the original band of pilgrims at Plymouth Rock on the Mayflower in 1620. Allegedly, Billington was prone to profane language. During the journey over the ocean, the ship’s captain, Miles Standish, had Billington’s feet and neck tied together as an example of a sin-struck man possessed of a Devil’s tongue. But that’s not what got him hanged; it was an unpleasant experience for the blasphemer. However, ten years later, Billington became the prime suspect in the murder of another settler named John Newcomen. Soon, the man was summarily hanged by an angry mob of pilgrims in 1630.

The earliest recorded female hanged in America was Jane Champion in 1632 in Virginia for an unknown offense. Up until the late 1640s, hangings of men during these early pilgrim times were usually caused by sexual offenses such as sodomy or beastiality, and women were most often hanged for concealing a birth. However, this all began to change in 1647 when many began to be hanged for practicing witchcraft.

Guilty of “flapping his hands and arms” and “behaving in a peculiar manner,” Thomas Hellier, a 14-year-old white boy, became a suspect in a rash of thefts and was sentenced to a life of bondage on a Virginia plantation. Never agreeable to his humble status, Hellier was sold several years later to a harsh taskmaster named Cutbeard Williamson. After Williamson, Williamson’s wife, and a maid were murdered with an ax while they slept one night, Hellier was assumed to be the murderer and hanged by a mob on August 5, 1678. His body was lashed with chains to a tall tree overlooking the James River, where it remained for several years until it rotted away.

Culminating in 1692, men and women were hanged after the notorious witchcraft trials in Salem, Massachusetts. One of these notorious cases was four-year-old Dorcas Good, convicted of witchcraft and sent to prison in 1692. She was the daughter of Sarah Good, who was one of the first three people accused of witchcraft. Little Dorcas was taken to prison with her mother, and she confessed to practicing witchcraft at one point. Her mother certainly told her to do that to save her life. As it turned out, Sarah Goode was hanged on July 19, 1692, and her little daughter stayed in prison for several more months. When she was finally released, she had lost her mind. Later, her father petitioned the authorities for help in taking care of her.

During the American Revolution, the term ‘lynch law’ originated with Colonel Charles Lynch, a Virginia planter, and his associates, who began to make their own vigilante rules for confronting the British Tories, loyalists to England, and other criminal elements.

This type of rough justice was also used regularly by whites against their African American slaves. Those white men who protested were often in danger of being lynched themselves. One such man was Elijah Lovejoy, editor of the Alton [Illinois] Observer, who was shot by a white mob after publishing articles criticizing lynching and advocating the abolition of slavery.

After the revolution, the most common hangings of white men were due to war-related crimes such as spying, espionage, treason, or desertion. Blacks were summarily hanged at the will of their owners, most often for the “official” reason of revolt. However, it could have been for any cause and merely “labeled” as such. Whites who sympathized with the slaves were also often hanged.

During this time, vigilantism arose without formal criminal justice systems. Most often called vigilance committees, these groups got together to blacklist, harass, banish, “tar and feather,” flog, mutilate, torture, or kill people perceived as threats to their communities or families. By the late 1700s, these committees became known as lynch mobs because almost all the time, the punishment handed out was a summary execution by hanging.

In the first part of the 19th century, opponents of slavery, cattle rustlers, horse thieves, gamblers, and other “desperadoes” in the South and the Old West were the most common targets of those not of African American descent. Meanwhile, hangings, burnings, and whippings continued to kill slaves with common regularity.

Montana holds the record for the bloodiest vigilante movement from 1863 to 1865, when hundreds of suspected horse thieves were rounded up and killed in massive mob actions. Texas, Montana, California, and the Deep South, especially the city of New Orleans, Louisiana, were hotbeds of vigilante activity in American history.

“Lynching” was easily accepted as the nation expanded west to the frontier, where raw conditions encouraged swift punishment for real or imagined criminal behavior. Vigilance committees, consisting of several dozens to several hundred men, formed quickly and summarily decided to execute to repress crime. Even where official law enforcement did exist, prisoners were sometimes dragged from jail by a lynch mob and executed.

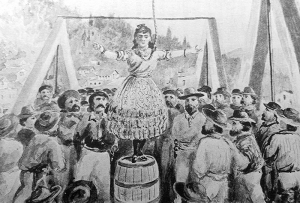

One of the first recorded hangings in the West of a woman was in 1849 when miners pioneered the boomtowns of California, where gambling, drinking, violence, and vigilante justice were common. One woman, “Pretty Juanita,” was convicted of murder after stabbing a man who had tried to rape her. Before she was hung, she laughed and saluted as the rope pulled tight around her neck. She was the first person hanged in the California mining camps.

On June 2, 1850, five Cayuse Indians were hanged in Oregon City, Washington, for the Whitman Massacre. All five had turned themselves in to spare their people from persecution. Before the execution, one of the condemned, Tiloukait, said: “Did not your missionaries teach us that Christ died to save his people? So we die to save our people.”

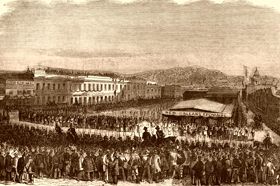

In June 1851, an Australian with a bad reputation became the first victim of San Francisco’s vigilance committee. Caught in stealing a safe, Jenkins, along with three other Australians from Sydney, were subjected to a mock trial, then marched to San Francisco’s Custom House, where they all had nooses put around their necks and were hanged on the spot. A second San Francisco “vigilance” committee was formed in 1856 and lynched two men, James P. Casey and Charles Cora. Casey had shot and killed a newspaper editor named James King, who had been bolding assaulting evildoers in his newspaper. Charles Cora, an Italian gambler, had shot and killed a U.S. marshal named Richardson in November 1855.

A mob of about 6,000 persons either helped to perpetrate or witnessed the lynching of the two men. Casey and Cora were seized and hanged from projecting beams rigged on the roof of a building on Sacramento Street. Before the mob dissipated, two more unidentified men were hung from the beams for unknown reasons.

Other non-vigilante lynchings were also occurring with regularity, such as the hanging of two slaves on July 11, 1856, in South Carolina for aiding a runaway slave, and the hanging of four black male slaves on December 5 of the same year, allegedly for “revolting” against the state of Tennessee.

Though lynchings were always more prone to blacks, two white criminals were in Iowa in 1857, one for murder and the other for counterfeiting and theft.

April 9, 1859, saw Colorado’s first execution in Denver. John Stoefel was hanged for shooting his brother-in-law. Both men were gold prospectors, and Stoefel wanted his brother-in-law’s gold dust. Because the nearest official court was in Leavenworth, Kansas, a “people’s court” was assembled, where Stoefel was convicted and hanged within 48 hours of the murder. Though Denver consisted of only 150 buildings then, about 1,000 spectators attended the Stoefel hanging.

Meanwhile, trouble has been brewing along the Kansas/Missouri border over the issue of slavery for several years. The fanatical activist John Brown had primarily participated in what became known as “Bleeding Kansas.” John Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859, at Charles Town, West Virginia. Two weeks later, on December 16, Shields Green and John Anthony Copeland, two of five African-American conspirators, were hanged for participating in John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry. Copeland was led to the gallows shouting, “I am dying for freedom. I could not die for a better cause. I had rather die than be a slave.”

In the Antebellum days of Texas between 1846 and 1861, vigilantes instigated most lynchings. Often, these vigilantes imitated legal court procedures, trying the offender before a vigilante judge and jury.

Though convictions most often resulted in whipping, 140 offenders were lynched during this time frame. Vigilante groups increased in frequency with the approach of the Civil War when mobs frequently sought out suspected slave rebels and white abolitionists.

The tension came to a head on September 13, 1860, when abolitionist Methodist minister Anthony Bewley was lynched in Fort Worth, Texas. Bewley, born in Tennessee in 1804, had established a mission 16 miles south of Fort Worth by 1858. When vigilance committees alleged in the summer of 1860 that there was a widespread abolitionist plot to burn Texas towns and murder their citizens, suspicion immediately fell upon Bewley and other outspoken critics of slavery.

Recognizing the danger, Bewley left for Kansas in mid-July with part of his family. A Texas posse caught up with him near Cassville, Missouri, and returned him to Fort Worth on September 13. Late that night, vigilantes seized Bewley and delivered him into the hands of a waiting lynch mob. His body was allowed to hang until the next day, when he was buried in a shallow grave. Three weeks later, his bones were unearthed, stripped of their remaining flesh, and placed on top of Ephraim Daggett’s storehouse, where children made a habit of playing with them.

But the violence in Texas did not end with Bewley. As rumors continued of a slave insurrection, it led to the lynching of an estimated 30 to 50 slaves and possibly more than 20 whites over the next two years. The entire affair culminated in the greatest mass lynching in the state’s history, in what is now called “The Great Hanging at Gainesville.” During 13 days in October 1862, vigilantes hanged 41 suspected Unionists.

During the same year, the Sioux Uprising in Minnesota resulted in more than 500 dead white settlers on August 17th. Reacting to broken government promises and corrupt Indian agents and going hungry when promised food was not distributed, the uprising began when four young Sioux murdered five white settlers in Acton, Minnesota. A military court sentenced 303 Santee Sioux to die, but President Abraham Lincoln reduced the list to 38. Outraged, several hundred white civilians tried to lynch the 303 Santee Sioux on December 4, 1862. The soldiers, protecting the prisoners at a camp on the Minnesota River, were able to stop the angry crowd. However, on December 16, 1862, the 38 condemned Indian prisoners were hanged in Mankato, Minnesota, an event known as the largest mass hanging in United States history. Afterward, the government nullified the 1951 treaty with the Santee Sioux.

Active Civil War tensions were brewing everywhere, and on January 23, 1863, Confederate soldiers hanged a Fort Smith, Arkansas attorney. Martin Hart had previously served in the Texas legislature, where he spoke out against succession. However, when Texas became a part of the Confederacy, Martin resigned from his government post. Soon, he organized the Greenville Guards, pledging the company’s services “in defense of Texas” against invasion. Though he was under a Confederate commission, he spied against the Confederacy. In Arkansas, he led a series of rear-guard actions against Confederate forces and is alleged to have murdered at least two prominent secessionists. He was captured on January 18 by Confederate forces and hanged five days later.

More tension was brewing in New York City when its male population was called to war. On July 13, 1863, three days of massive anti-draft protests began. In the nation’s bloodiest riot in history, 50,000 Civil War draft protesters burned buildings, stores, and draft offices and actively attacked the police. Protestors clubbed, lynched, and shot large numbers of blacks, whom they blamed for the government’s position. When troops returning from Gettysburg finally restored order, 1,200 were dead.

While the rest of the nation was busy fighting the Civil War, American history’s deadliest vigilante justice campaign erupted in the Rocky Mountains.

The Montana Vigilantes were fighting violent crime in a remote corner beyond the reach of the government. Sweeping through the gold-mining towns of southwest Montana, the armed horseman hanged 21 troublemakers in the first two months of 1864 alone. One of these so-called troublemakers was elected Sheriff Henry Plummer, who was said to be the leader of a band of Road Agents called the Innocents.

After hanging Plummer, his two main deputies were also hanged on January 10, 1864. The Vigilantes hung more bandits in Sellgate (Missoula), Cottonwood (Deer Lodge), Fort Owen, and Virginia City. Though some of these Montana Vigilantes are still revered in Montana as founding fathers, historians have provided evidence that the whole thing regarding Sheriff Plummer and his Road Agents may very well have been a fraud.

Evidence suggests that many of the early stories on which the outlaw tales were based were written by the Virginia City Newspaper’s editor, a member of the vigilantes. The story was fabricated to cover up the real lawlessness in the Montana Territory – the vigilantes themselves. Furthermore, the robberies in Montana did not cease after the twenty-one men were hanged in January and February of 1864. In fact, after the “Plummer Gang” hangings, the robberies showed more evidence of organized criminal activity, and the number of thefts increased.

Random lynchings continued in Montana Territory throughout the 1860s, even though territorial courts were in place. Over six years, they lynched more than 50 men without trials until a backlash against extralegal justice finally took hold around 1870. However, by the decade’s end, Montana was again stirring with new settlements as railroad construction pushed westward. The vigilantes again became active by threatening “undesirables” to leave the territory. Reliance on mob rule in Montana became so ingrained that in 1883, a Helena newspaper editor advocated a return to “decent, orderly lynching” as a legitimate tool of social control.

Meanwhile, back on the Civil War battlegrounds, soldiers were being hanged by the dozens for crimes such as guerrilla activity, espionage, and treason, but most often for desertion. One such major spectacle was between February 5th and February 22nd, 1864, when 22 deserters were executed by hanging at Kinston, North Carolina.

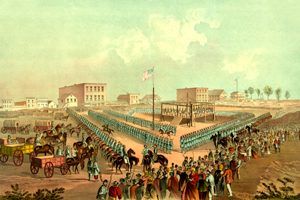

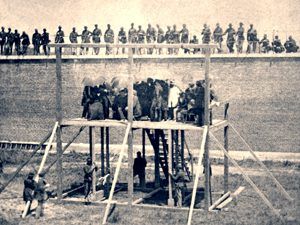

Legal hangings were performed regularly, the most public of which was the execution of the conspirators who were found guilty of killing Abraham Lincoln in 1865, just days after the close of the long and bloody Civil War. Mortally wounded by John Wilkes Booth’s bullet, Booth escaped but was shot down 12 days later in his hiding place.

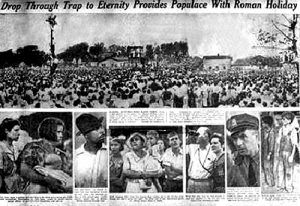

Execution of Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt on July 7, 1865, at Fort McNair in Washington City. Photo by Alexander Gardner.

Mourning the loss of Lincoln, the government began a full-scale investigation, identifying eight members of a conspiracy team, including one woman named Mary Surratt. Four of these conspirators were hanged before hundreds of spectators on July 7, 1865, in the courtyard of the Old Arsenal Penitentiary in Washington, D.C. Mary Surratt was the first woman ever legally executed by the federal government of the United States.

These public spectacles of death for legal hangings and lynchings often took on a festival-type atmosphere. Families attended with picnic baskets in hand, vendors sold souvenirs, and photographers took multiple photographs of the event, many of which wound up on penny postcards. It wasn’t until many decades later that public executions in the U.S. ceased in 1936.

From the ashes of the ruthless and costly Civil War, a violent stage was set for outlaws, vigilante justice, and mob violence that killed thousands of black men, women, and children. Upon the founding of the Ku Klux Klan in Tennessee, the lynching of African Americans grew to epidemic proportions. “Lynching” took on a new meaning as illegal hangings were soon attributed primarily to racist activities. From this time onward, mob violence was increasingly reflected in America’s contempt for racial, ethnic, and cultural groups – especially those of the black population.

But it didn’t stop there. These racial prejudices also extended to Native Americans, Mexicans, Asian immigrants, and European newcomers.

Ku Klux Klan Rally.

Youth was no bar to execution by these vicious people, as on February 7, 1868, a 13-year-old African-American girl named Susan was hanged in Henry County, Kentucky, for murder. Susan, a babysitter, was accused of killing one of her charges.

The newspapers helped to make these hangings more public by reporting items such as this one that appeared: “She writhed and twisted and jerked many times.” After her death, many purportedly “solid citizens” asked for a piece of her hanging rope as a souvenir.

Lynchings during this time also targeted white men and women who were known to interfere with “Judge Lynch justice” against the blacks, those who had aided runaways, Union activists, and abolitionists.

Lynching in the Wild West also increased after the Civil War as it experienced its most brazen period of extralegal hangings. Though often focused as either a deterrent to crime or a resolution to political disputes, waves of indiscriminate terror were waged against Mexicans, Chinese immigrants, and Native Americans. In many western territories, no legal authority existed, so the vigilantes took it upon themselves to dispense justice. In others, these Old West pioneers were too enraged or impatient to await the legal decisions.

However, not all of the hangings in the Wild West were performed by vigilantes. One such instance was the hanging of John Millan in Virginia City, Nevada, on April 24, 1868. Millan was accused of killing a popular prostitute named Julia Bulette. Bulette, who began her one-woman operation in 1861, was so popular among the locals that she rode in the Fourth of July Parade and was made an honorary member of the local fire department. On January 20, 1867, Julia was found strangled in her home with her jewels and furs missing. On the day of her funeral, every mine in the area shut down, and 16 carriages filled with the town’s leading men followed the hearse to the cemetery. Several weeks later, John Millan was arrested for her murder. While awaiting trial, Virginia City’s wives treated him like a hero, bringing him cakes and wine in jail. Found guilty, he was sentenced to hang. On April 24, 1868, crowds gathered from all over the state to watch Millan die on the gallows constructed one mile outside town.

Back in the turbulent South, Wyatt Outlaw, a town commissioner in Graham, North Carolina, was lynched by the Ku Klux Klan on February 26, 1870. Outlaw, the president of the Alamance County Union League of America (an anti-Ku Klux Klan group), helped establish the Republican party in North Carolina and advocated establishing a school for African Americans. The Klan hanged him from an oak tree near the Alamance County Courthouse. Dozens of Klansmen were arrested for the murders of Outlaw and other African Americans in Alamance and Caswell Counties. Many of the arrested men confessed, but despite protests by Governor William W. Holden, a federal judge in Salisbury ordered them released.

Later the same year, on the raw frontier of the West, gunfighter Clay Allison sat brooding about a locally convicted murderer by the name of Charles Kennedy. While drinking in an Elizabethtown, New Mexico saloon on October 7th, he soon stirred up sentiment against Kennedy. He led a lynch mob across the street to the jail in no time, where they dragged Kennedy screaming from his cell. He was then taken to a local slaughterhouse, where he was hanged, and his body was mutilated with huge knives used for butchering cattle. Allison cut the body down and, using an ax, chopped Kennedy’s head off and jammed it onto a pole. Then, Allison rode his horse to Cimarron, New Mexico, where he displayed the head on the bar of Henry Lambert’s saloon. Later, someone stuck it on the corral fence at the St. James Hotel, where it remained for months and was eventually mummified.

During this time, former slaves and free black men continued to be executed, such as ten black men on October 19, 1870, in Clinton, South Carolina. In November, four black men were lynched in Coosa County, Alabama; four were lynched in Noxubee County, Mississippi, and a federal revenue agent was hanged in White County, Georgia.

Lynchings continued earnestly in the South and the Old West over the next few years. In 1873, Klansman laid siege to Colfax, Louisiana, which black Union army veterans defended. On Easter Sunday, April 13, armed with a small cannon, the whites overpowered the defenders and slaughtered 50 blacks and two whites after surrendering under a white flag.

While hangings were taking place all over the South and the Wild West, one of the most famous was that of Jack “Broken Nose” McCall on March 1, 1877. Having gone to Deadwood, South Dakota, in 1876, using the name of Bill Sutherland, he sat in on a poker game with Wild Bill Hickok. Despite losing all his money, Wild Bill generously gave him enough money to buy breakfast but advised him not to play again until he could cover his losses. Humiliated, McCall shot Hickok in the back of the head the next day. He left Deadwood after killing Hickok but was later arrested in Laramie, Wyoming, brought back to Yankton, and put on trial for Hickok’s death. Found guilty, he was sentenced to hang. On March 1, 1877, he stood trembling on the scaffold, begging for someone to save him. He was buried in Yankton in an unmarked grave with the rope still around his neck.

James Miller, a 23-year-old man described as a “mulatto,” was the first man to be sent to the gallows after Colorado achieved statehood in 1876. Miller, a former soldier, was convicted of shooting and killing a man who had earlier forced him, at gunpoint, to leave a dance hall reserved for whites. When Miller was hanged in West Las Animas on February 2, 1877, the trap door would initially not open.

When it eventually fell, the trap door detached and came to rest on the ground. Miller dropped, but the hanging rope was too long, and Miller’s feet came to rest on the trap door below. The trap door was then removed so that Miller could swing freely. He then strangled for 25 minutes before expiring. The local sheriff, reportedly distraught over the botched execution, resigned and left town.

In what has become known as “Pennsylvania’s Day With the Rope,” the state hung eleven “Molly Maguire” coal miners in the East for murder and conspiracy. Their real crime was attempting to organize the mine workers. On June 21, 1877, all of them were hanged for their “obstinacy.”

The “ethnic cleansing” of Chinese from the American West was another dark chapter in our nation’s history. Writes John Higham in Strangers in the Land, “No variety of anti-European sentiment has ever approached the violent extremes to which anti-Chinese agitation went in the 1870s and 1880s.” Many of the estimated 200 American lynchings victimizing people of Asian descent occurred during this time.

In 1880, many Chinese lived in Hop Alley, Denver, Colorado’s Chinatown. In October of that year, an anti-Chinese riot resulted in the lynching of a Chinese man and injuring many others. A mob of approximately 3000 people had gathered in Hop Alley, consisting of “illegal voters, Irishmen and some Negroes.” Only eight Policemen were on duty at the outbreak of the riot. Firemen, brought in to disperse the crowd, hosed them with water, making them angrier. The mob began to destroy Chinese businesses, loot their homes, and injure many. According to the Rocky Mountain News, the Chinese quarter was “gutted as completely as though a cyclone had come in one door and passed out the rear. There was nothing left…whole.”

It is difficult to identify the youngest person legally executed in American history, but records indicate that a ten-year-old Cherokee Indian boy was hanged for murder in 1885.

On October 28, 1889, Katsu Goto was a merchant, interpreter, and lynching victim. He spoke fluent English and was a contract laborer who took over a store in Honokaa, Hawaii, a plantation village. His customers were not only Japanese, as he was, but also Hawaiian and Haole (white). White plantation owners disliked him, and his popularity in the community created competition with shopkeepers loyal to the white Protestant overseers.

Nine days before he was lynched, on October 19th, a fire broke out at the nearby Overend Camp, and Goto and seven other workers were accused of arson. Though he never had a trial, four men ambushed and killed Goto. His body was found swinging from a telephone pole the next day. After a lengthy investigation, the perpetrators were arrested, tried, and sentenced to O’ahu Prison.

After a black rape suspect was forcibly taken from a county jail and lynched in front of a crowd of 9,000 people in Ohio, the Cleveland Leader published this editorial on June 19, 1897, which echoed the sentiments of many of the American people.

“The people of Ohio have seen murderers tried and convicted of murder in the 1st degree two or three times over and finally set free. They have known many desperate and dangerous criminals to be sent to the penitentiary for long terms and released soon enough to make the whole costly process of the courts seem little better than a farce… That is the real reason why, once in a while, the passion and indignation of the masses break through all restraints, and some particularly wicked crime is avenged… “

In 1891, several Italian Americans were accused and arrested for the murder of the local police chief. At the news of the not guilty verdict, hysteria took hold of a crowd of several thousand citizens, who stormed the jail where the former suspects were held. On March 14, 1891, eleven Italian Americans were dragged into the streets, beaten, and hanged. “Public opinion around America generally endorsed the mob’s action, applauding the citizens’ efforts to stop the mafia. As a result, President Benjamin Harrison was the first resident to request a federal law against Lynching later that year. An incident in New Orleans and the recurring violence against African Americans was becoming an international human rights embarrassment.

Despite its reputation for violence, Tombstone, Arizona, saw only one lynching during its history, and miners conducted that from nearby Bisbee, Arizona. When six men held up the Goldwater and Castenada Store in Bisbee in December 1883, three men and a pregnant woman were shot and killed. While five robbers were sentenced to be hanged, one named John Heath was found guilty of second-degree murder and given life imprisonment. This so enraged the people of Bisbee that a group went to Tombstone on February 22, 1884, removed Heath from the sheriff’s custody, and lynched him from a telegraph pole at the corner of First and Toughnut Streets. The other five men were legally hanged at Tombstone, March 6, 1884.”

Back in the south, Ida Wells, an editor for a small newspaper in Memphis, Tennessee called the Free Speech, investigated the many lynchings in 1884. She discovered that white mobs had hung 728 black men and women in just a short period. Of these deaths, two-thirds were for minor offenses such as public drunkenness and shoplifting.

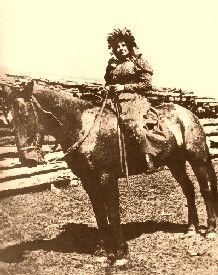

Ellen Watson, aka “Cattle Kate.”

There were occasions when people were lynched for political reasons or greed. For example, on July 20, 1889, James Averell and Kate Watson, aka “Cattle Kate,” were lynched on the orders of Albert J. Bothwell, a powerful cattleman in Wyoming. Unfortunately, Averell and Watson had become involved in a dispute with Bothwell during the Johnson County range war. Bothwell responded by organizing a vigilante mob, perpetuating a story of how the pair had been involved in cattle rustling and they were lynched.

A couple of days later, on July 23, 1989, in Fayette, Missouri, 19-year-old Frank Embree was accused of raping a fourteen-year-old white girl. Embree maintained his innocence but confessed after having been whipped over 100 times, crying, “he would ‘own-up’ if they would ‘hang me or shoot me, instead of torturing me.”‘ Frank Embree died at the end of a rope without a trial.

By the 1890s, lynchers had become particularly sadistic when blacks were the prime targets. Burning, torture, and dismemberment were increasingly used to prolong the suffering. Sadly, these tactics were also utilized to create a more “festive atmosphere” among the onlookers. Public spectacles became more common as newspapers carried advance notices and railroad agents sold excursion tickets announcing lynching sites. As families brought their children to these “recreational” events, executioners cut off black victims’ fingers, toes, ears, and genitalia as souvenirs. Often, these racially motivated lynchings were not spontaneous mob reactions but were carried out with the assistance of law enforcement.

Though many at the time were under the false impression that these multiple lynchings were taking place for violations against women and were rightly justified, this was rarely the case. More often, their alleged crimes included such offenses as using offensive language, having a bad reputation, refusing to give up a farm, throwing stones, unpopularity, slapping a child, and stealing hogs, to name a few. In East Texas, a black man and his three sons were lynched for the grand crime of “harvesting the first cotton of the season.” Only 19% of those lynched were ever charged with rape. Fewer were ever proven.

On March 9, 1892, a cold-blooded lynching occurred in Memphis, Tennessee. Three young men of color, in an altercation at their place of business, fired on white men in self-defense. They were imprisoned for three days, taken out by a mob, shot, and lynched. Thomas Moss, William Stewart, and Calvin McDowell were energetic businessmen who had built a flourishing grocery business.

Their business had prospered, and that of a rival white grocer named Barrett had declined. Barrett led the attack on their grocery, which resulted in the wounding of three white men. No effort was made to punish the murderers of these three men.

Ida Wells was exiled from her home in 1892 under penalty of death for writing articles about lynching in her small newspaper.

When Ida Wells, editor of Free Speech, wrote an article condemning the lynchers, a white mob destroyed her printing press. They declared that they intended to lynch her, but fortunately, she was visiting Philadelphia then. This led Ida to write more on the topic and begin the Anti-lynching Campaign, a movement to end mob violence against African-Americans that would last through the 1940s.

However, her property was soon destroyed, and she was exiled from her home under the penalty of death for writing the following editorial, printed in her paper.

The Free Speech, in Memphis, Tennessee, on May 21, 1892:

“Eight Negroes lynched since last issue of the ‘Free Speech’ one at Little Rock, Ark., last Saturday morning where the citizens broke (?) into the penitentiary and got their man; three near Anniston, Ala., one near New Orleans; and three at Clarksville, Ga., the last three for killing a white man, and five on the same old racket—the new alarm about raping white women. The same program of hanging and then shooting bullets into the lifeless bodies was carried out to the letter. Nobody in this section of the country believes the old threadbare lie that Negro men rape white women. If Southern white men are not careful, they will over-reach themselves, and public sentiment will have a reaction; a conclusion will then be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.”

The Memphis Daily Commercial Appeal called her a “Black scoundrel,” White businessmen threatened to lynch the owners of her newspaper, and creditors commandeered the newspaper’s offices and sold the equipment.

1892 ended up being the worst year for lynchings in America, with 69 whites hanged and 161 blacks killed at the hands of lynch mobs.

By the turn of the century, the Old West had instituted official legal entities throughout the states, and most vigilante groups had disappeared. From there on out, almost all of the lynchings that occurred in the 20th century were either racially or politically motivated.

The international response, condemning the U.S. for lynching foreign citizens residing in the U.S., resulted in the State Department having to pay out hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages to foreign governments. Between 1887 and 1903, a total of $480,000 was paid to the governments of China, Italy, Great Britain, and Mexico alone. During this time, Americans traveling abroad routinely encountered critical commentaries in foreign newspapers and magazines condemning the common practice of lynching in the United States.

How could America, these foreign critics asked, champion human rights abroad when it failed to prevent and punish the most brutal human rights violations at home?

Between 1880 and 1905, not one person was ever convicted of any crime associated with these killings. Lynchings are, in effect, the most extensive series of unsolved murders in American history.

In 1901, George Henry White, the last former slave to serve in Congress, proposed a bill to make anyone involved in lynching a federal crime. He pointed out that white mobs primarily used lynching in the South to terrorize African Americans. He supported his proposal by showing statistics that of the 109 people lynched in 1899, 87 were African Americans. However, the bill was defeated.

On October 8, 1902, a town mob of 500 in Newbern, Tennessee, lynched two black men named Garfield Burley and Curtis Brown. Burley had confessed to killing a well-known young farmer near Dyersburg, Tennessee, named D. Fiatt over a horse trade. Later, when Burley demanded that the trade be declared off, Fiatt refused, and Burley shot him down when Fiatt was on his way home.

When a posse apprehended Burley, he implicated Curtis Brown as an accomplice. When the mob appeared and demanded possession of the prisoners, Criminal Court Judge Maiden pleaded to the group to allow the law to deal with the case, stating that the two men would be placed on trial the very next day. However, the mob would not listen. The prisoners were taken to a telephone pole, where they were securely tied face to face and strung up.

On August 3, 1906, the mob numbered into the thousands when five black men — Nease, John Gillespie, Jack Dillingham, Henry Lee, and George Irwin– were lynched in Salisbury, North Carolina. Accused of murdering members of a local family named Lyerly, the victims were tortured with knives before being hanged and then riddled with bullets. The authorities in North Carolina, alarmed at one of the largest multiple lynchings of the 20th century, took unusual steps to punish the mob’s leaders. After the Governor ordered the National Guard to restore order, local officials arrested more than two dozen suspected leaders. One of the killers, George Hall, was convicted and sentenced to 15 years of hard labor in the state penitentiary. The New York Times predicted that, by taking these measures, North Carolina’s Governor Glenn was not improving his political prospects.

On January 9, 1907, an atypical lynching victim was taken from the Floyd County Jail in Charles City, Iowa. James Cullen, a wealthy, white, 62-year-old contractor, had murdered his wife and 15-year-old stepson, Roy Eastman, the day before. Young men orchestrated the mob, perhaps acquainted with the ill-fated Eastman. When the group of several hundred men rammed down the jail doors with a rail iron, the sheriff and several deputies offered only feeble resistance. Seizing Cullen, they hanged him from the local Main Street Bridge. By 11:30 p.m., a crowd of at least 500 residents, including women and children, had gathered to view the swaying body of James Cullen hanging from the bridge.

In 1908, eight black men were lynched on June 24th near Hemphill, Texas. The trouble began when a local man named Dean was shot, and six black men were arrested in connection with the crime. Soon, a mob stormed the jail, taking the six men and hanged them on the same tree. Later the same evening, another black man was shot; the next morning, two more African American corpses were found hanging from trees near the town.

On August 1st of the same year, four men were hanged simultaneously in Logan County, Kentucky. Joseph Riley, Virgil, Robert, and Thomas Jones were discontented sharecroppers in Russellville, Kentucky, with whom a man named Rufus Browder was a friend and lodge brother. When Browder and James Cuningham, the farmer for whom he worked, had an argument, Browder turned away when Cunningham cursed him and struck him with a whip. Cunningham then drew his pistol and shot Browder in the chest. Browder, in self-defense, returned the fire and killed Cunningham. After having his wounds tended to, Browder was arrested and sent to Louisville for his own protection.

Subsequently, the three Jones men and Riley were conducting a lodge meeting in a private home when police entered and arrested them for disturbing the peace. In fact, they were arrested for having expressed approval of Browder’s actions and discontentment with their employers. On August 1, 1908, 108 men entered the jail and demanded the prisoners. The jailer complied, and the four men were hanged from the same tree. A note pinned to one of the men read, “Let this be a warning to you ni**ers to let white people alone, or you will go the same way.”

Another vigilante mob killed a notorious killer named Jim Miller, also known as Killin’ Jim. Miller, sometimes known as “Deacon Jim” for his Sunday preachings, killed more than 30 men in Texas and Oklahoma as one of the first known “killers for hire.” When the law finally caught up with him, he was sentenced to death, but Miller only laughed. The finest criminal lawyers in the West were on his payroll, and he soon bragged that he would be released after his attorney filed their appeals. However, a crowd of vigilantes did not wait for these legal procedures. They knew Miller, who had often bragged of his many killings, might cheat justice through his highly paid lawyers.

On the night of April 19, 1909, a lynch mob broke into the jail in Ada, Oklahoma, and dragged Miller and three others out to a livery stable. Though the other men begged for their lives, Jim “The Killer” Miller showed no signs of fear. He only asked that his diamond ring be given to his wife and that he be permitted to wear his black Stetson while he was being hanged. The vigilantes granted these wishes. Then Miller, standing on a box, displayed his last act of bravado, shouting, “Let ‘er rip!” He then voluntarily stepped off the box to be jerked by the rope around his neck, which was tied to a rafter in the stable. He dangled as the other three were strung up. The bodies were left hanging for some hours to allow a local photographer to take enough photos of the lynchings — these photos were sold for many years in Ada, Oklahoma, to tourists. The only surviving photo shows Miller hanging with the others, his black hat on his tilted head.

In Texas, the publicity of the lynching provoked even more attacks on Mexicans. Because Mexicans “displayed an impudent attitude,” they were attacked in Galveston. In construction camps and ranches in Webb, Duval, LaSalle, Dimmit, and Starr Counties, Anglos attacked Mexicans who were reportedly “sullen and threatening since the burning of Rodriquez at Rock Springs.”

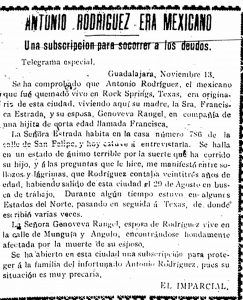

In the American Southwest, people of Mexican descent were also prey to ‘mob’ violence, as evidenced by the lynching of Antonio Rodriquez on November 3, 1910, in Rock Springs, Texas. Allegedly, Rodriquez killed a white woman named Mrs. Clem Hernderson after the two had an argument. Rumors circulated that he had committed the murder in front of Mrs. Henderson’s five-year-old daughter.

In the American Southwest, people of Mexican descent were also prey to ‘mob’ violence, as evidenced by the lynching of Antonio Rodriquez on November 3, 1910, in Rock Springs, Texas. Allegedly, Rodriquez killed a white woman named Mrs. Clem Hernderson after the two had an argument. Rumors circulated that he had committed the murder in front of Mrs. Henderson’s five-year-old daughter.

His guilt was based solely upon her husband’s third-hand description of the suspect delivered over the telephone. Most likely, Rodriquez was the victim of a tragic case of mistaken identity. The young cowboy was captured, taken a mile outside of town, tied to a mesquite tree, doused in kerosene, and burned alive.

Widely publicized in the Mexican press, the lynching in Texas led to large anti-American demonstrations in Mexico City and Guadalajara. Coverage of the lynching and the reaction to it was wildly sensationalized. The newspapers at the capitol of Mexico demanded, ‘Where is the boasted Yankee civilization?'”

In late April 1911, a posse visited the Nelson cabin in Oklahoma, suspecting Mr. Nelson of stealing cattle. While they were looking for meat, Nelson’s 14-year-old son, L.W., shot and killed Deputy George Loney, who was in charge of the posse. Laura Nelson, the boy’s mother, claimed to have shot the deputy to protect her son. Both mother and son were taken to the Okemah County jail. Days later, Mr. Nelson pled guilty to stealing cattle and was sent to prison.

While Laura and her son awaited their trials, Laura was determined to be innocent of the crime. However, on May 25, forty men stormed the sheriff’s office. The jailer, named Payne, lied that the two prisoners had been moved elsewhere, but when a revolver was “pressed into his temple,” he led them to the prisoners. Mother and son were then hauled by wagon six miles west of town to a steel bridge crossing the Canadian River and hanged.

The following day, a black boy taking his cow to water discovered the two bodies swaying under the bridge. Before long, the scene had attracted hundreds of viewers before the bodies were cut down. No one was ever arrested for the crime.

One local newspaper said of the lynching: “While the general sentiment is adverse to the method, it is generally thought that the Negroes got what would have been due them under the process of law.”

Amazingly, even the black folks got wrapped up in the lynching craze when they lynched three of their own people on September 12, 1911, in Wickliffe, Kentucky. Three black men, by the names of Ernest Harrison, Sam Reed, and Frank Howard, confessed to the murder of Washington Thomas, an older and much respected black man. When Thomas, employed in a tobacco factory, was walking home from work, the three men waylaid him along the railroad tracks, robbing him of his salary and killing him. The offenders were quickly apprehended and placed in jail. However, a mob of blacks invaded the jail during the night, took the prisoners, and hanged them to a cross beam in a mill near the river.

Bennie Simmons, or Dennis Simmons, accused of the murder of 16-year-old Susie Church, was taken from prison guards in Anadarko, Oklahoma, on June 13, 1913. His killers led him to a nearby bridge and hanged him from the limb of a cottonwood tree flourishing by a stream.

The Eufaula Democrat would report the following on the lynching:

“The Negro prayed and shrieked in agony as the flames reached his flesh,” reported a local newspaper, “but his cries were drowned out by yells and jeers of the mob.” As Simmons began to lose consciousness, the mob fired at the body, cutting it to pieces. “The mobsters made no attempt to conceal their identity, but there were no prosecutions.”

On August 17, 1915, a Jewish-American factory manager, Leo Frank, was hanged from a tree in Marietta, Georgia, by a mob of 25 men. Frank had been convicted of murdering Mary Phagan, a 13-year-old employee of the Atlanta pencil factory that Frank had managed two years earlier. His trial attracted international attention, turning the spotlight on anti-Semitism in the United States and leading to the founding of the Anti-Defamation League. Though he was sentenced to death, his sentence was later commuted by Georgia’s governor.

On August 17, 1915, a Jewish-American factory manager, Leo Frank, was hanged from a tree in Marietta, Georgia, by a mob of 25 men. Frank had been convicted of murdering Mary Phagan, a 13-year-old employee of the Atlanta pencil factory that Frank had managed two years earlier. His trial attracted international attention, turning the spotlight on anti-Semitism in the United States and leading to the founding of the Anti-Defamation League. Though he was sentenced to death, his sentence was later commuted by Georgia’s governor.

Soon after the commutation, on August 16, 1915, a group of 25 men stormed the Milledgeville Prison hospital where Leo Frank was recovering from having his throat slashed by a fellow inmate. They kidnapped Frank, drove him more than 100 miles to Mary Phagan’s hometown of Marietta, Georgia, and hanged him from a tree. Frank conducted himself with dignity, calmly proclaiming his innocence.

People came from all over to celebrate by digging their heels into the face of the dead man, and, like the vultures, they carved up Frank’s clothing to take home as “souvenirs.” Before the body was cut down, photographers took snapshots of the scene, which were sold in rural Southern drugstores for years.

The mob included two former Superior Court justices, one ex-sheriff, and at least one clergyman. After his extrajudicial death, evidence emerged that he was innocent of the murder charge brought against him. Leo Frank represents one of only four cases of a Jewish American being lynched in United States history. (There was a case of a double lynching of a Negro and a Jew in Tennessee in 1868; there were two other cases of American Jews lynched in the 1890s.)

The tragedies continued. One such terrible ordeal was the killing of Jesse Washington, a 17-year-old black youth who worked on a farm belonging to George and Lucy Fryer in Robinson, Texas.

In nearby Waco, Washington, he was convicted and confessed to raping and killing Mrs. Fryer on May 15, 1916. Sentenced to death by hanging, residents were in an uproar over the crime and were unwilling to wait for justice to follow its course. They hurried him down the stairs at the rear of the courthouse, where a crowd of about 400 persons waited in the alley. A chain was thrown around Washington’s neck, and he was dragged toward the City Hall, where another group of vigilantes had gathered to build a bonfire underneath a large tree.

He was stripped naked and beaten with clubs, shovels, and bricks. Before a crowd of some 15,000 people, including the Police Chief, Waco’s Mayor, and police officers, Washington was immersed in coal oil, hoisted onto the tree, and slowly lowered into the fire. After his death, many spectators cut off fingers and toes to keep as souvenirs. Two hours later, several men placed the burned corpse in a cloth bag and pulled the bundle behind an automobile to Robinson, Texas, some seven miles south of Waco, where they hung the corpse from a pole in front of a blacksmith’s shop for public viewing.

The “Waco Horror” stood as a vivid reminder that though the frequency of lynchings had begun to decline in the United States after 1900, those incidents that still occurred were often characterized by extreme barbarity.

The lynching mania continued, resulting in one of the most bizarre hangings in history – that of an elephant on September 13, 1916, in Erwin, Tennessee. According to circus posters of the day, Big Mary, at 5 tons, was said to be the biggest elephant in captivity and was one of the stars of Sparks World Famous Shows. Though the details of her crimes have gotten lost in history, Ripley’s Believe It Or Not reported in 1938 that Mary was responsible for killing three people, while rumors said as many as eight. What is known for certain is that the elephant killed her trainer, Walter “Red” Eldridge, on September 12th. Attempts to shoot her to death failed, so it was decided to hang her from a railroad derrick car until she died. A crowd of between 2,500 and 5,000 witnessed the vigilante justice.

Though not as often hanged as black men, women were also the targets of vicious lynchings, such as Mary Turner in Valdosta, Georgia, in May 1918. Turner, whose husband had been killed at the hands of a mob, made the mistake of making “unwise” remarks after he was killed. Mr. Turner had not committed any offense; however, another black man killed a white farmer. In retaliation, many of the white citizens of Valdosta lynched eleven black men before they shot and killed the man they were after. Mr. Turner was one of those men in the wrong place at the wrong time during the mob’s frenzied vendetta.

After her husband’s murder, Mary, who was eight months pregnant, vowed to avenge those who killed her husband. For her remarks, a mob of several hundred white men and women determined they would “teach her a lesson.” Turner’s ankles were tied together, and she was hanged upside down from a tree, doused with gasoline, and burned. After her clothes burned off and while she was still alive, a man sliced open her abdomen with a hog-splitting knife. Her unborn infant fell from her womb, gave two screams, and then had its head crushed by mob members who stomped on it.

Mary Turner’s body was then riddled with bullets. Turner and her child were hastily buried about ten feet from the execution site. An empty whiskey bottle and a cigar marked their graves. After the lynchings, more than 500 African Americans left the vicinity of Valdosta, leaving hundreds of acres of untilled land behind them.

Walter White, who later investigated the lynching for the NAACP, was told by one eyewitness, “Mister, you ought to’ve heard that n***er wench howl.” The lynching was recounted in numerous articles and editorials and discussed in Congress. It became a rallying point to obtain federal anti-lynching legislation. A month later, on July 26, 1918, President Woodrow Wilson issued a national appeal to stop lynching, stating:

“There have been lynchings, and every one of them has been a blow at the heart of ordered law and human justice. No man who loves America, no man who really cares for her fame and honor and character, or who is truly loyal to her institutions can justify mob action. At the same time, the courts of justice are open, and the Government of the United States and the nation are ready and able to do their duty.

“I therefore very earnestly and solemnly beg that the governors of all the States, the law officers of every community, and above all, the men and women of every community in the United States, all who revere America and wish to keep her name without stain or reproach, will cooperate, not passively merely, but actively and watchfully to make an end to this disgraceful evil.”

During World War I, lynching declined, but the year it ended in 1918, it started up again, as evidenced by this statement in the Charleston newspaper: “There is scarcely a day that passes that newspapers don’t tell about a Negro soldier lynched in his uniform.” The following year, more than seventy black men were lynched, including ten black soldiers still in uniform. The “Red Scare” of 1919 was overshadowed by the racial violence and lynching fever that was termed, by James Weldon Johnson, as “the Red Summer.” During that summer, there were twenty-six race riots in such cities as Chicago, Illinois; Elaine, Arkansas; Charleston, South Carolina; Knoxville and Nashville, Tennessee; Longview, Texas; and Omaha, Nebraska. Over 100 black people were killed in these riots, and thousands were wounded and homeless.

Racial tensions were at an extreme in Omaha, Nebraska; the influx of African Americans from the South and a perceived epidemic of crime created an atmosphere of mistrust and fear that led to the lynching of William Brown.

Brown had been accused of assaulting a white woman. When police arrested him on September 28, 1919, a mob quickly formed, ignoring orders from authorities to disperse. When Mayor Edward P. Smith appeared to plead for calm, he was kidnapped by the mob, hung to a trolley pole, and nearly killed before police could cut him down.

The rampaging mob set the courthouse prison on fire and seized Brown. He was hung from a lamppost, mutilated, and his body riddled with bullets, then burned. Four other people were killed and fifty wounded before troops could restore order.

Between 1919 and 1922, statistics show that another 239 were lynched. What is unknown is the number killed by individual acts of violence and unrecorded lynchings. No one was ever punished for these crimes.

On June 1, 1921, one of the worst race riots in history occurred in Tulsa, Oklahoma. “Black Wall Street,” the name fittingly given to one of the most affluent black communities in America, was bombed from the air and burned to the ground by mobs of envious whites. In a period spanning fewer than 12 hours, the thriving black business district in north Tulsa lay smoldering; 3,000 black Americans were dead, and over 600 successful businesses were lost.

Behind the destruction was the Ku Klux Klan, working in consort with ranking city officials and many other sympathizers. It cost the black community everything, and not a single dime of restitution nor insurance claims were ever awarded to the victims. Many of the dead were buried in mass graves around the city; some were thrown into the river, and others were thrown into a coal mine.

In 1922, another anti-lynching bill was drafted and passed in the House of Representatives but was defeated in the Senate, and again, the tragedies continued to occur. In the 1930s, the depression fueled the hunt for racial and political scapegoats.

Souvenir photos and postcards of lynching became a lost genre of American photography when the Postmaster General finally banned such postcards from going through the mail in the mid-1920s. Small-town photographers, who had made large profits from the thousands of penny postcards, were disappointed to lose a large part of their business. Though lynching photography continued, they at least stopped going through the mail.

In 1925, Price, Utah, saw the last lynching of a black man in the American West. Robert Marshall, an itinerant miner, was hanged after two white boys said they had seen him near the scene where a white man was murdered. A thousand people watched the hanging, but not one person testified before a grand jury who carried out the lynching.

The drama of these horrible spectacles seemed to increase over time, with the lynch leader often dressed in a garish costume and bandying about numerous objects, such as lynch ropes, the American flag, guns, and gasoline, in or to create an atmosphere of even higher excitement. Further, the sadistic nature of the crowds also increased. Such was the case when James Irwin was lynched on January 31, 1930. Accused of the murder of a white girl in Ocilla, Georgia, Irwin was taken by a rampaging mob. As people cheered and children played during the festivities, his fingers and toes were cut off, his teeth pulled out by pliers, and then he was castrated. He was then burned alive in front of hundreds of onlookers. Afterward, onlookers fired rifles and handguns hundreds of times into the corpse, and pieces of the body were taken as souvenirs of the event. No one was ever punished for this barbaric killing.

On the night of August 7, 1930, three young African Americans — Thomas Shipp, age nineteen; Abram Smith, age eighteen; and sixteen-year-old James Cameron, faced the hideous wrath of a lynch mob in the Ku Klux Klan-dominated town of Marion, Indiana. Only Cameron survived. The black youths had been involved in the robbery-inspired murder of Claude Deeter, 23, a white factory worker from nearby Fairmount, Indiana. They were accused of sexually assaulting Deeter’s white girlfriend, nineteen-year-old Marion resident Mary Ball. While the latter charge was never proven, such charges, however groundless, were easily assumed by racist whites and frequently served to incite lynch mobs to commit even greater atrocities.

Both Shipp and Smith were snatched from a jail cell only a block and a half from the giant oak tree, where their bodies were soon to hang lifeless, beaten, and hanged to death by the furious mob. Cameron was badly beaten and nearly suffered an identical demise but was saved at the last moment by the intervention of a “voice” from the crowd. “That boy didn’t have anything to do with killing or raping!” shouted the voice. Cameron’s mysterious benefactor was never identified. Later, James Cameron would write a book entitled A Time of Terror, from which the following account was taken.

Both Shipp and Smith were snatched from a jail cell only a block and a half from the giant oak tree, where their bodies were soon to hang lifeless, beaten, and hanged to death by the furious mob. Cameron was badly beaten and nearly suffered an identical demise but was saved at the last moment by the intervention of a “voice” from the crowd. “That boy didn’t have anything to do with killing or raping!” shouted the voice. Cameron’s mysterious benefactor was never identified. Later, James Cameron would write a book entitled A Time of Terror, from which the following account was taken.

“Thousands of Indianans carrying picks, bats, ax handles, crowbars, torches, and firearms attacked the Grant County Courthouse, determined to “get those goddamn N***ers.” A barrage of rocks shattered the jailhouse windows, sending dozens of frantic inmates searching for cover. A sixteen-year-old boy, James Cameron, one of the three intended victims, paralyzed by fear and incomprehension, recognized familiar faces in the crowd — schoolmates and customers whose lawns he had mowed and whose shoes he had polished — as they tried to break down the jailhouse door with sledgehammers. Many police officers milled outside with the crowd, joking. Inside, fifty guards with guns waited downstairs.

The door was ripped from the wall, and a mob of fifty men beat Thomas Shipp senselessly and dragged him into the street. The waiting crowd ‘came to life.’ It seemed to Cameron that ‘all of those ten to fifteen thousand people were trying to hit him all at once.’ The dead Shipp was dragged with a rope up to the window bars of the second victim, Abram Smith. For twenty minutes, citizens pushed and shoved for a closer look at the ‘dead n***er.’ By the time Abe Smith was hauled out, he was equally mutilated. ‘Those who were not close enough to hit him threw rocks and bricks. Somebody rammed a crowbar through his chest several times in great satisfaction.’ Smith was dead when the mob dragged him ‘like a horse‘ to the courthouse square and hung him from a tree. The lynchers posed for photos under the limb that held the bodies of the two dead men.

Then the mob headed back for James Cameron and ‘mauled him all the way to the courthouse square,’ shoving and kicking him to the tree, where the lynchers put a hanging rope around his neck. Cameron credited an unidentified woman’s voice with silencing the mob and opening a path for his retreat to the county jail and, ultimately, for saving his life. Mr. Cameron has committed his life to retelling the horrors of his experience and ‘the Black Holocaust‘ in his capacity as director and founder of the museum with the same name in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Under magnification, one can see the girls in this photo clutching ragged swatches of dark cloth.

“After souvenir hunters divvied up the bloodied pants of Abram Smith, his naked lower body was clothed in a Klansman’s robe — not unlike the loincloth in traditional depictions of Christ on the cross. Lawrence Beitler, a studio photographer, took this photo. For ten days and nights, he printed thousands of copies, which sold for fifty cents apiece.”

In its sporadic occurrences over the following decades, lynching continued to be a vehicle of terror and a last resort in opposition to the drive for political and civil rights through the 1950s, 1960s, and beyond.

The NAACP hoped that the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 would finally end lynching. A new bill was drafted in 1935 to punish sheriffs who failed to protect their prisoners from lynch mobs. However, Roosevelt would not speak out in favor of the bill, arguing that white voters in the South would never forgive him and he would lose the next election.

When the corpse of Brooke Hart, a San Jose youth, was discovered in San Francisco Bay on November 26, 1933, a mob materialized to punish the alleged kidnappers and murderers, Thomas H. Thurmond and John “Jack” Holmes. The lynchers rammed open the jail door, assaulted the guards, and dragged Holmes and Thurmond to St. James Park, beating them into near unconsciousness. Holmes’s clothes were sheared from his body, and Thurmond’s pants were drawn down to his ankles. A gathering of some six thousand spectators witnessed the hanging.

Governor James Rolph’s doublespeak was typical of many lynching-era politicians: “While the law should have been permitted to take its course, the people by their action have given notice to the entire world that in California, kidnapping will not be tolerated.”

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black body swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant South,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of magnolias sweet and fresh,

And the sudden smell of burning flesh.

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for a tree to drop,

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

From Billie Holiday’s 1938 song Strange Fruit.

On December 6, 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt used one of his first national radio addresses to call lynch law “collective murder” and condemn those “in high places or in low who condone lynch law.” Alluding to the growing number of federal anti-lynching legislation supporters, he stated that a new generation of Americans “seeks action… and is not content with preaching against that vile form of collective murder — lynch law — which has broken out in our midst anew.” Though Roosevelt spoke out against lynching, he still would not support the anti-lynching proposed laws.

On October 26, 1934, Claude Neal was lynched in Marianna, Florida. This lynching had a traumatic effect on the nation’s approval of lynching. The young black man was lynched after confessing to the murder of Lola Cannidy. The methods used to extract the confession cast doubt on its validity. Ms. Cannidy, a young white neighbor, was supposedly having an affair with Neal. To ensure Claude’s safety, he was kept in an Alabama jail. The lynch mob took him from the authorities and subjected him to ten hours of excruciating torture and mutilation before he was murdered.

Neal’s body was tied to a rope at the rear of an automobile and dragged over the highway to the Cannidy home. Here, a mob estimated to number somewhere between 3000 and 7000 from eleven southern states was excitedly awaiting his arrival. It was then taken back to Marianna, where it was hung to a tree on the northeast corner of the courthouse square. Pictures were taken of the mutilated form, and hundreds of photographs were sold for fifty cents each. Neal’s fingers were sold as souvenirs to the bloodthirsty crowd who arrived too late to witness the gory festivities.

This situation was even more deplorable because the Florida press had advance notice of the lynching and reported it in their newspapers. However, no local, state, or federal officials tried to prevent the lynching. A race riot followed Neal’s lynching in Marianna, where white rioters attempted to drive all blacks out of the city.

While the Neal lynching may have been the last “spectacle” lynching in the nation, many other lynchings of a less publicized nature would follow. Marianna would be the site of another lynching less than ten years later.

On July 19, 1935, a woman named Marion Jones in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, complained about a black man who had appeared at her door.

In no time, Rubin Stacy was picked up by authorities, and while he was being escorted to the Dade County jail in Miami, Florida, he was forcibly taken by a white mob. The mob returned the 32-year-old man to Fort Lauderdale and hanged him outside Jones’ home. However, the investigation revealed that Stacy was nothing more than a homeless tenant farmer who had gone to the Jones home, asking for food. When Marion Jones saw him, she became frightened and screamed. The white mob had never even given Stacy the chance to discover the facts before he died at the end of a rope.

Even the appearance in the newspapers of these lynchings failed to change Roosevelt’s mind on speaking out for another anti-lynching bill proposed after Stacey’s murder. Though the proposed bill received more support than it had in the past, it was defeated. However, the national debate taking place over the issue helped bring attention to the crime of lynching to the American public.

Be it lynchings or legal hangings, the spectacle of death was most often a public event until 1936. The last legal execution made public occurred in the early morning of August 14, 1936, when a crowd of 20,000 gathered to watch the public hanging of Rainey Bethea in Owensboro, Kentucky. Bethea, a 22-year-old black man, had been convicted of the rape and murder of a seventy-year-old white woman. Hundreds of reporters and photographers, some from as far away as New York and Chicago, were sent to Owensboro to cover what was supposed to be the country’s first hanging conducted by a woman.

The county sheriff was a woman named Florence Thompson, a widow and mother of four, who deliberately had the scaffold erected so that thousands could witness the execution. The execution was widely publicized, as much for the execution itself, like the fact that the executioner was to be the first female to ever act as such. So many people invaded Owensboro for the spectacle that terrified local blacks who fled the town, especially after receiving lynching threats from many drunken white revelers. As the crowd waited all night to witness the execution at dawn, parties developed among the anxious crowd as the many children hawked snacks in the festive atmosphere.

The large crowd included over 200 sheriffs and deputies from various parts of the U.S., and other than just six black people, the throbbing mass was made up of completely whites. Except for those elbowing for a better position, the crowd remained well-behaved.

Before Bethea’s arrival, the hangman tested the knot, and when it snapped open, a loud cheer went up from the onlookers. But, of Sheriff Florence Thompson, there was no sign.

Shortly after sunrise, Bethea walked out of jail, accompanied by a Catholic priest, Father Lemmons, and two deputies. When he arrived at the top of the gallows, he was given the chance to give his last words, but instead, he stood silent as Father Lemmons raised his hand to hush the crowd. Phil Hanna, who’d supervised 70 Southern hangings, pulled a long black hood over Bethea’s head and the noose around his neck.

One wire service dispatch read: “Cheering, booing, eating and joking, 20,000 persons witnessed the public execution of Rainey Bethea, 22, frightened Negro boy, at Owensboro, Ky., yesterday. In callous, carnival spirit, the mob charged the gallows after the trap was sprung, tore the executioner’s hood from the corpse, and chipped the gallows for souvenirs. Mothers attended with babes in arms, hot dog vendors hawked their wares, and a woman across the street held a necktie breakfast for relatives. At the last minute, the woman sheriff decided not to spring the trap.”

An embarrassed Kentucky General Assembly quickly abolished public executions; before long, those states still sanctioning public executions followed suit. Rainey Bethea was the last man publicly executed in the United States.

Falling eight feet, the rope tightened and broke Bethea’s neck. The still-warm body was then attacked by souvenir hunters, tearing off pieces of clothing and some even attempting to cut pieces of flesh from the poor man’s body. The spectators were backed away so that two physicians could examine the body, and when a pulse was found, a large groan went up from the crowd. From when the trapdoor fell to when Bethea was pronounced dead at 5:45 a.m., 14 minutes had passed. When the final determination was made that the man was officially a corpse, several people began fighting over the hood that covered his head. Only 37 days had elapsed between his arrest and his execution.

After Bethea’s body was hauled away in a pauper’s basket, Sheriff Florence Thompson told reporters that she had decided against flipping the lever herself because “I did not want people pointing to my children and saying their mother was the one who hanged a Negro at Owensboro.”

Afterward, the reporters, who had paid dearly to get to the “boonies,” rushed off to write their stories. Many people contend that in their disappointment to see the first woman in U.S. history perform an execution, they took their anger out against the spectators and the town of Owensboro. Exaggerating an event that needed no further embellishment, the headlines cried: “The Center of Barbarism,” “Children Picnic as Killer Pays,” and “They Ate Hot Dogs While a Man Died on the Gallows.”

In 1937 and again in 1940, two more anti-lynching bills passed through the House of Representatives but were defeated in the Senate. Although the NAACP failed to pass a federal law, lynchings had almost disappeared by 1950. The NAACP’s 30-year struggle to publicize the barbarity of lynch mobs had penetrated even the most backward and racist regions of the country.

Not one single event alone spurred the people to action when the Civil Rights Movement was finally born. Instead, the Movement developed out of the post-World War II society in the mid-1950s and early 1960s. Instead, each struggle and its subsequent achievement altered the tone of society and the expectations of present and future generations.

As a reaction to the Civil Rights Movement, southerners revived the ever-effective lynching, which had been in decline, to combat the movement’s achievements. The violent deaths were inflicted both on locals who attempted to work within their own community and on “outside agitators” from such Civil Rights organizations as the Congress of Racial Equality, who attempted to maintain the status quo of Southern society through the implicit threat of the lynch mob. Lynching, however, had the opposite of its intended effect. Instead of silencing the black population and dissuading them from organizing, several well-publicized lynchings galvanized the Civil Rights movement, introduced a national audience to the violence inflicted by an archaic social order, and even forced the federal government to become involved in what had been a state government concern.

Even after the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, lynchings persisted in the Deep South, the most significant of which was the illegal execution of 19-year-old Michael Donald.

In 1981, a black man charged with the murder of a white policeman stood trial in Mobile, Alabama. When his trial took place, the jury could not reach a verdict. Upset Ku Klux Klan members believed that some black jury members had affected this outcome. At a meeting after the trial, Bennie Hays, the second-highest-ranking official in the Alabama Klan, said: “If a black man can get away with killing a white man, we ought to be able to get away with killing a black man.”

On Saturday, March 21, 1981, Bennie Hays’ son, Henry Hays, and James Knowles decided they would get revenge for the failure of the courts to convict the African American for killing a policeman.

Traveling around Mobile in their car, they soon found Michael Donald walking home. Donald had nothing to do with the murder of the police officer and was in no way involved in the trial. He was just an innocent man whom the Ku Klux Klan chose randomly to exact revenge for the acquittal of the other man during the trial. When the pair spotted Michael Donald, they forced him into their car, drove to the next county, and lynched him.

An investigation resulted in the local police finding that Donald had been murdered over a bad drug deal. However, Beulah Mae Donald knew her son was not involved in drugs and resolved to obtain justice. Soon, Jessie Jackson and the FBI were involved, and it was not long before FBI agent James Bodman could obtain a confession from James Knowles.

In June 1983, Knowles was found guilty of violating Donald’s civil rights and was sentenced to life imprisonment. Six months later, when Henry Hays was tried for murder, Knowles appeared as the chief prosecution witness. Hays was found guilty and sentenced to death.

But Beaulah Mae Donald was not yet done with her determination to obtain justice. She soon filed a civil suit against the United Klans of America. In February 1987, an all-white jury found the Klan responsible for the lynching of Michael Donald and ordered it to pay 7 million dollars. This resulted in the Klan handing over all its assets, including its national headquarters in Tuscaloosa.

After a long-drawn-out legal struggle, Henry Hayes was executed on June 6, 1997. It was the first time a white man had been executed for a crime against an African American since 1913.

Through the years, other forms of capital punishment, such as the electric chair and, more recently, lethal injection, have largely replaced hanging in the U.S. today. The most recent hanging in the United States occurred on January 25, 1996, when Delaware hanged Billy Bailey; Delaware has since abolished the method. Hanging remains legal only in Washington State, which last used it to execute Charles Campbell on May 27, 1994. In 1996, the State legislature amended the law to make lethal injection the default death penalty unless the convicted person chooses to hang. Today, the gallows and firing squads are anything but public and are rarely used in the United. States.

However, hanging remains the second most widely used method of execution in the world today (the first is shooting), and in some places, they remain public. In 2002, at least 115 men and five women were hanged in ten countries; in 2002, at least 99 men and one woman; and in 2004, at least 150 men and seven women suffered this fate.

Lynchings: By State and Race, 1882-1968 (Statistics provided by the Archives at Tuskegee Institute)

| State | White | Black | Total |

| Alabama | 48 | 299 | 347 |

| Arizona | 31 | 0 | 31 |

| Arkansas | 58 | 226 | 284 |

| California | 41 | 2 | 43 |

| Colorado | 65 | 3 | 68 |

| Delaware | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Florida | 25 | 257 | 282 |

| Georgia | 39 | 492 | 531 |

| Idaho | 20 | 0 | 20 |

| Illinois | 15 | 19 | 34 |

| Indiana | 33 | 14 | 47 |

| Iowa | 17 | 2 | 19 |

| Kansas | 35 | 19 | 54 |

| Kentucky | 63 | 142 | 205 |

| Louisiana | 56 | 335 | 391 |

| Maine | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Maryland | 2 | 27 | 29 |

| Michigan | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| Minnesota | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| Mississippi | 42 | 539 | 581 |

| Missouri | 53 | 69 | 122 |

| Montana | 82 | 2 | 84 |

| Nebraska | 52 | 5 | 57 |

| Nevada | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| New Jersy | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| New Mexico | 33 | 3 | 36 |

| New York | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| North Carolina | 15 | 86 | 101 |

| North Dakota | 13 | 3 | 16 |

| Ohio | 10 | 16 | 26 |

| Oklahoma | 82 | 40 | 122 |

| Oregon | 20 | 1 | 21 |

| Pennsylvania | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| South Carolina | 4 | 156 | 160 |

| South Dakota | 27 | 0 | 27 |

| Tennessee | 47 | 204 | 251 |

| Texas | 141 | 352 | 493 |

| Utah | 6 | 2 | 8 |

| Vermont | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Virginia | 17 | 83 | 100 |

| Washington | 25 | 1 | 26 |

| West Virginia | 20 | 28 | 48 |

| Wisconsin | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Wyoming | 30 | 5 | 35 |

| TOTAL | 1,297 | 3,446 | 4,743 |

Statistics provided by the Archives at Tuskegee Institute.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.

Also See: