Cooke County and the city of Gainesville, Texas, became an area of building tension before and during the Civil War. Geographically located closer to “Free-State” Kansas than to the capitol of Austin, they were a diverse set of people. Having extremely mixed origins, about half the emigrants came from the Deep South and wanted to continue their traditions of an Old South planter lifestyle, though very few of them were wealthy enough to own slaves. The other half came primarily from the Upper South and principally made their livings as ranchers. In September 1858, when the Butterfield Stage Line made its way to the area, it brought with it an even more diverse group from all areas of the nation.

Over the next several years, tensions began to mount between slave owners and abolitionists. In the summer of 1860, several slaves and a northern Methodist minister were lynched in North Texas. The following year, the statewide vote on Secession was held in February 1861. Cooke County’s population was comprised of only about 11% slaves, and by a margin of 61%, the county, along with others in North Texas, voted it down.

However, with only 19 of the 122 counties voting against succession, they were resoundingly defeated. Almost immediately, the editor of the Sherman Patriot, E. Junius Foster, called for North Texas to secede from Texas and stay in the Union as a free state. This, along with rumors of Unionist alliances with Kansas Jayhawkers and Indians along the Red River, brought the tension to a fever pitch. Despite the protests of the Unionists, secession soon became a reality, and many of those who had opposed secession, realizing that their opinions put them in danger, fled to Kansas or California. Others, however, chose to stay, which placed them in a vulnerable position.

After Texas seceded, the Confederacy promised that the citizens living in Texas would be of the greatest value by defending the state from within its borders, and no one would be drafted to fight the United States outside of the state. However, the Conscription Act of 1862 changed this, making only landholders with large numbers of slaves exempt from the draft.

This upset several men who did not “fit” within the exemption status, and 30 of them responded with a signed Petition of Protest, which was sent to the Confederate Congress in Richmond, Virginia. Brigadier General William R. Hudson, who commanded the militia district in the area, responded by exiling newspaper editor and leader of the petition, E. Junius Foster, from the area. However, a few months later, the remaining petitioners began enlisting people into a group called the Union League in Cooke and nearby counties. Before long, Gainesville became the focal point of protests.

This early “Union League” was loosely organized, and though some were Unionists, others joined to resist the draft. Others joined to provide a common defense against roving Indians and renegades. However, rumors began circulating that the group had grown to about 1,700 men who had plans to assault the militia arsenals at Gainesville and Sherman. The Confederates soon got worried that the rumors were true. In late September 1862, Brigadier General William R. Hudson ordered the arrest of all able-bodied men who had not reported for duty.

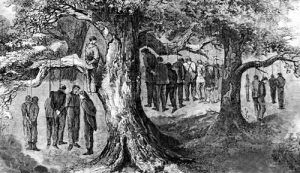

On the morning of October 1, 1862, Hudson sent Colonel James G. Bourland, who was one of the largest slaveholders in a county, to arrest those who had not reported for duty. Bourland, along with the Texas state troops, soon rounded up more than 150 men who were accused of insurrection or treason. Bourland and Colonel William C. Young of the Eleventh Texas Cavalry then handpicked 12 jurors to serve on a “citizen’s court.” Seven of the jurors were slaveholders, and Bourland mandated that a conviction did not require a unanimous vote, only a majority vote. Seven of those accused men were sentenced to hang, but before the “court” was finished, 14 more were lynched by an angry mob.

The very next week, Colonel William C. Young was assassinated. This enraged the Confederates, and several previous defendants were tried again. This time, 19 more were condemned to be hanged, taking the death toll to 40 in Gainesville. Two others were shot as they tried to escape. However, the man suspected of killing William C. Young was not among these men, and the Colonel’s son, Captain Jim Young, personally tracked him down and ordered his slaves to hang him. Jim Young also killed E. Junius Foster, the editor of the Sherman Patriot, who had applauded the assassination of Colonel William Young. Five more men were killed in Decatur, and one in Denton before the madness ran its course.

The mass executions became known as the Great Hanging at Gainesville. They were generally applauded by the Texas newspapers, insisting that the Unionists were terrorists, common thieves, and conspiring with Kansas abolitionists. The state government also condoned the actions. However, when Confederate President Jefferson Davis learned of the affair, he dismissed General Paul Octave Hebert as military commander of Texas for his improper use of martial law.

The unrest continued when Confederate Brigadier General Albert Pike, who was in charge of Indian Territory, was implicated as a Unionist and arrested. Although he was later released, he continued to be regarded with suspicion and served the rest of the war in civilian offices.

In Arkansas, a North Texas company of Confederates almost mutinied when they heard about the mass hangings. Though Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby calmed the situation down, several men later deserted.

Powerless to exact revenge, many members of the Union League fled the state.

Once the Civil War had ended, there was a half-hearted prosecution of those who were responsible for the mass execution; however, it resulted in the conviction of only one man.

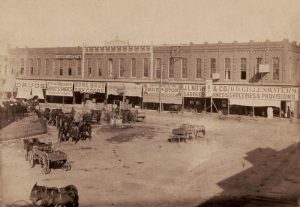

The Great Hanging of Gainesville is commemorated only by a small monument just west of the intersection of California Street and U.S. Highway I-35 in Gainesville, Texas.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2024.

Also See: