World War I was a war like no other, and U.S. participation in this global conflict had a profound impact on those who fought and on the nation’s future.

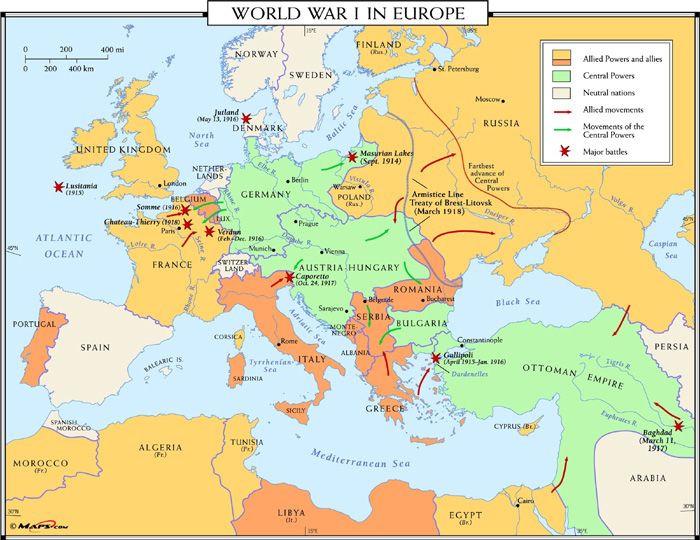

War broke out in Europe in the summer of 1914, after months of international tension. The spark that ignited open hostilities was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, and his wife Sophie in Sarajevo, Bosnia. By the end of the year, the Central Powers, led by Germany and Austria-Hungary, were battling the Allies, led by Britain, France, and Russia.

The United States initially declared itself neutral, leading to years of arguing over whether to join the conflict. The debates surrounding isolationism and interventionism took place in popular culture and the arts, as well as in the political sphere and the news.

During his tenure as President, Woodrow Wilson encouraged the country to look beyond its economic interests and to define and set foreign policy in terms of ideals, morality, and the spread of democracy abroad.

The United States continued its efforts to become an active player on the international scene. It engaged in action both in its traditional “sphere of influence” in the Western Hemisphere and Europe during the First World War. The Wilsonian vision for collective security through U.S. leadership in international organizations.

The sinking of the British ocean liner Lusitania on May 7, 1915, killed almost 1,200 people, including more than 120 U.S. citizens. Many Americans, appalled that the German submarines, or U-boats, would sink a passenger ship, saw this as a brutal attack on freedom of movement and U.S. neutrality. The Lusitania was one of dozens of ships sunk carrying American passengers and goods.

Following the sinking of an unarmed French boat, the Sussex, in the English Channel in March 1916, Wilson threatened to sever diplomatic relations with Germany unless the German Government refrained from attacking all passenger ships and allowed the crews of enemy merchant vessels to abandon their ships before any attack. On May 4, 1916, the German Government accepted these terms and conditions in what came to be known as the “Sussex Pledge.”

By January 1917, however, the situation in Germany had changed. During a wartime conference that month, representatives from the German Navy convinced the military leadership and Kaiser Wilhelm II that a resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare could help defeat Great Britain within five months. German policymakers argued that they could violate the “Sussex Pledge” since the United States could no longer be considered a neutral party after supplying munitions and financial assistance to the Allies. Germany also believed that the United States had jeopardized its neutrality by acquiescing to the Allied blockade of Germany.

German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg protested this decision, believing that resuming submarine warfare would draw the United States into the war on behalf of the Allies. This, he argued, would lead to the defeat of Germany. Despite these warnings, the German Government decided to resume unrestricted submarine attacks on all Allied and neutral shipping within prescribed war zones, reckoning that German submarines would end the war long before the first U.S. troopships landed in Europe. Accordingly, on January 31, 1917, the German Ambassador to the United States, Count Johann von Bernstorff, presented U.S. Secretary of State Robert Lansing with a note declaring Germany’s intention to restart unrestricted submarine warfare the following day.

Germany’s resumption of submarine attacks on passenger and merchant ships in 1917 became the primary motivation behind Wilson’s decision to lead the United States into World War. While Wilson weighed his options regarding the submarine issue, he also had to address the question of Germany’s attempts to cement a secret alliance with Mexico. On January 19, 1917, British naval intelligence intercepted and decrypted a telegram sent by German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann to the German Ambassador in Mexico City. The “Zimmermann Telegram” promised the Mexican Government that Germany would help Mexico recover the territory it had ceded to the United States following the Mexican-American War. In return for this assistance, Germany asked for Mexican support in the war.

President Wilson went before Congress on February 3 to announce that he had severed diplomatic relations with Germany. However, he refrained from asking for a declaration of war because he doubted that the U.S. public would support him unless he provided ample proof that Germany intended to attack U.S. ships without warning. Wilson left open the possibility of negotiating with Germany if its submarines refrained from attacking U.S. shipping. Nevertheless, throughout February and March 1917, German submarines targeted and sank several U.S. ships, resulting in the deaths of numerous U.S. seamen and citizens.

On February 26, Wilson asked Congress for the authority to arm U.S. merchant ships with U.S. naval personnel and equipment. While the measure would probably have passed in a vote, several anti-war Senators led a successful filibuster that consumed the remainder of the congressional session. As a result of this setback, President Wilson decided to arm U.S. merchant ships by executive order, citing an old anti-piracy law that gave him the authority to do so.

The continued submarine attacks on U.S. merchant and passenger ships and the “Zimmermann Telegram’s” implied threat of a German attack on the United States swayed U.S. public opinion in support of a declaration of war. Furthermore, international law stipulated that the placing of U.S. naval personnel on civilian ships to protect them from German submarines already constituted an act of war against Germany. Finally, by their actions, the Germans had demonstrated that they had no interest in seeking a peaceful end to the conflict. These reasons all contributed to President Wilson’s decision to ask Congress for a declaration of war against Germany.

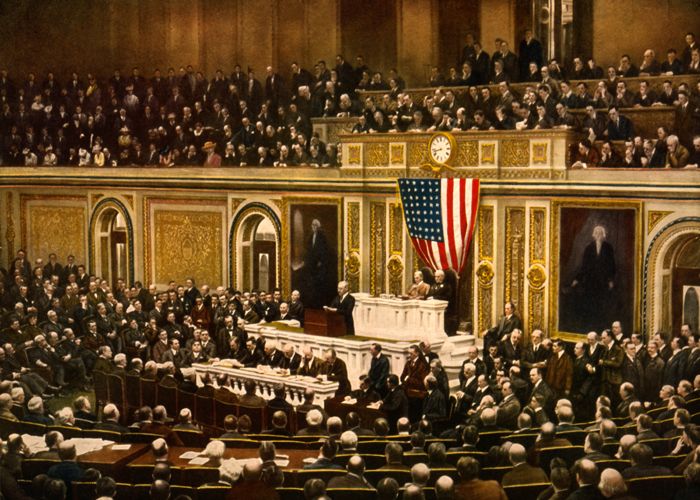

On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson went before a joint session of Congress to request a declaration of war against Germany. On April 4, 1917, the U.S. Senate voted to support the measure to declare war on Germany. The House concurred two days later. Later, the United States declared war on German ally Austria-Hungary on December 7, 1917.

Faced with mobilizing a sufficient fighting force, Congress passed the Selective Service Act on May 18, 1917. By the end of the war, the Selective Service Act had conscripted over 2.8 million American men. The hundreds of thousands of men who enlisted or were conscripted early in the war faced months of intensive training before departing for Europe.

The U.S. Congress passed the Espionage Act on June 15, 1917. The Act prohibited individuals from interfering with draft or military processes expanded the punishment for insubordination in the military and barred Americans from supporting enemies in war. Supporters saw it as a necessary precaution to promote domestic and military security. At the same time, critics viewed it as an attack on freedom of speech and argued that this law unfairly targeted immigrants and ideological dissenters.

To finance the extensive military operations of the war and help curb inflation by removing large amounts of money from circulation, the United States government issued Liberty Bonds. Bond drives, parades, advertisements, and community pressure fueled the purchase of bonds, which played a crucial role in financing the U.S. war effort.

When U.S. troops arrived overseas, they found themselves amid a war waged on the ground, in the air, and under the sea, using new weapons on an unprecedented scale. Combatants suffered casualties in quantities never before seen. Many U.S. soldiers recorded the experience of participating in such an overwhelming and sometimes disorienting conflict in diaries and letters home and poems and songs.

It was often regarded as the world’s first modern war; it used military technology, including tanks, airplanes, modern machine guns, and poison gas. Technological innovations extended beyond the military. The medical field also experienced new technologies, including blood transfusions, x-ray machines, and prosthetics. Communication systems drastically changed during the war, as the telephone was adapted to meet wartime conditions, and the wireless telegraph, a precursor to radio technology, became more widely used.

On November 11, 1918, an Armistice agreement effectively ended the fighting. The Central Powers’ surrender conditions were agreed upon when the Treaty of Versailles was signed on June 28, 1919. The Treaty assigned responsibility for the war to the Central Powers and required that they pay reparations for war damages. However, the burden fell mainly on Germany due to economic difficulties and Germany being the only defeated power with an intact economy.

In addition to drafting the Treaty, the Paris Peace Conference also formed the League of Nations, an organization intended to prevent aggressive conflict by uniting the world’s foremost military powers into one body. The U.S. Senate ratified neither the Versailles Treaty nor U.S. entry into the League of Nations, primarily out of opposition to mandatory U.S. military involvement in foreign conflicts.

Four empires disappeared in the aftermath of the war: the German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian. Numerous nations regained their former independence, and new ones were created. Austria-Hungary was partitioned into several successor states, including Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia. The Russian Empire lost much of its western frontier as the newly independent nations of Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland were carved from it.

World War I took the lives of more than nine million soldiers, and 21 million more were wounded. Civilian casualties caused indirectly by the war numbered close to 10 million. The two nations most affected were Germany and France, each of which sent some 80 percent of their male populations between the ages of 15 and 49 into battle.

World War I saw unprecedented participation by African American troops, with over 350,000 African American soldiers serving. However, African American troops were only able to serve in segregated units, and many were excluded from combat, allowed only to provide support services. The return of African American soldiers to their home communities after the war was followed by both a series of bloody racial conflicts and a wave of civil rights activism.

World War I led to dramatic changes in the United States. American women served in many capacities, including agriculture, factory and munitions work, the medical field, and non-combat roles in the Army, Navy, and Marines. The expanded role of women in the American workforce during the war was an important factor in the growing support for women’s suffrage and the eventual passing of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

Some hopeful participants Called World War I “the War to End All Wars.” But the Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919, would not achieve that lofty goal.

As the years passed, hatred of the Versailles Treaty and its authors settled into a smoldering resentment in Germany that would, two decades later, be counted among the causes of World War II. The harsh punishments of the Treaty and the ineffectiveness of the League of Nations led to the rise of Nazism and Fascism, which included the revival of the nationalist spirit, the rejection of many post-war changes, and the German populace to see themselves as victims.

Woman operating a punch press, at the Frankford Arsenal, Frankford, Pennsylvania during World War I.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2022.

Also See:

Learning Opportunities From Legends of America

Sources:

History.com

Library of Congress

Office of the Historian

Wikipedia