The Ku Klux Klan, commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is the name of several historical and current American white supremacist, far-right terrorist organizations and hate groups. Their primary targets are African Americans, Hispanics, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, Italian Americans, Irish Americans, Catholics, immigrants, leftists, homosexuals, Muslims, atheists, and abortion providers.

The Ku Klux Klan comprised three distinct U.S. hate organizations that employed terror to pursue their white supremacist agenda. One group was founded immediately after the Civil War and lasted until the 1870s. The second Klan group began in 1915 and continued to the 1940s. During the 1960s, as civil rights workers attempted to force Southern communities’ compliance with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Klan was revived.

The 19th-century Klan was initially organized as a social club by six Confederate veterans in Pulaski, Tennessee, shortly after the Civil War in December 1865. They derived the name from the Greek word kyklos, which means circle, with clan, and the Ku Klux Klan emerged. The Klan was a vigilante group mobilizing a campaign of violence and terror against the African American people who benefited from the progress of Reconstruction. As the group gained members from all classes of Southern white society, they used violent intimidation to prevent Black Americans — and any white people who supported Reconstruction — from voting and holding political office. They burned houses and attacked and killed Black people, leaving their bodies on the roads. The organization quickly became a vehicle for Southern white underground resistance to Radical Reconstruction.

While racism was a core belief of the Klan, antisemitism was not. Many prominent Southern Jews identified wholly with Southern culture, resulting in examples of Jewish participation in the Klan.

The first leader or “grand wizard” of the Ku Klux Klan was Nathan Bedford Forrest, a well-known Confederate general. Within the structure of the Klan, he directed a hierarchy of members with outlandish titles, such as “imperial wizard” and “exalted cyclops.” Hooded costumes, violent “night rides,” and the notion that the group made up an “invisible empire” conferred a mystique that only added to the Klan’s infamy.

Historians generally classify the KKK as part of the post-Civil War insurgent violence related to the high number of veterans in the population and their effort to control the dramatically changed social situation by using extrajudicial means to restore white supremacy. In 1866, Mississippi Governor William L. Sharkey reported widespread disorder, lack of control, and lawlessness; in some states, armed bands of Confederate soldiers roamed at will.

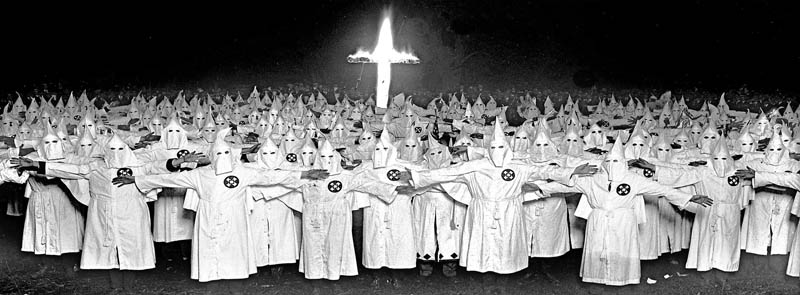

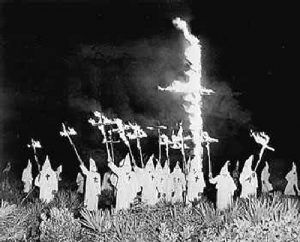

In the summer of 1867, a Klan convention was held in Nashville, Tennessee, that was attended by delegates from former Confederate states. The group was presided over by the grand wizard, Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, and a descending hierarchy of grand dragons, grand titans, and grand cyclopses. Dressed in robes and sheets designed to frighten superstitious Blacks and to prevent identification by the occupying federal troops, Klansmen whipped and killed freedmen and their white supporters in nighttime raids.

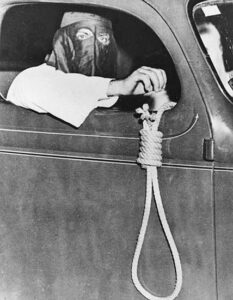

In 1868, the Klan, joined by other white Southerners, engaged in a violent campaign of deadly voter intimidation during the presidential election to maintain white government control. From Arkansas to Georgia, thousands of Black people were killed. Similar campaigns of lynchings, tar-and-featherings, rapes, and other violent attacks on those challenging white supremacy became a hallmark of the Klan.

The 19th-century Klan reached its peak between 1868 and 1870. A potent force, it was primarily responsible for restoring white rule in North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia. However, General Nathan Forrest ordered it disbanded in 1869, primarily due to the group’s excessive violence. Local branches remained active for a time, prompting Congress to pass the Force Act in 1870 and the Ku Klux Klan Act in 1871.

The first Klan had mixed results in terms of achieving its objectives. It seriously weakened the Black political leadership by using assassinations and threats of violence, and it drove some people out of politics. On the other hand, it caused a sharp backlash with the passage of federal laws.

The bills authorized the president to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, suppress disturbances by force, and impose heavy penalties upon terrorist organizations. President Ulysses S. Grant was lax in utilizing this authority. However, he did send federal troops to some areas, suspended habeas corpus in nine South Carolina counties, and appointed commissioners who arrested hundreds of Southerners for conspiracy. A grand jury convened in Columbia, South Carolina, in 1871 to investigate the activities of the Klan concluded, in part:

“During the whole session, we have been engaged in investigations of the most grave and extraordinary character — investigations of the crimes committed by the organization known as the Ku Klux Klan. The evidence elicited has been voluminous, gathered from the victims and their families and those who belong to the Klan and participated in its crimes. The jury has been shocked beyond measure at the developments made in their presence of the number and character of the atrocities committed, producing a state of terror and a sense of utter insecurity among a large portion of the people, especially the colored population.”

In United States v. Harris in 1882, the Supreme Court declared the Ku Klux Klan Act unconstitutional, but by then, the Klan had practically disappeared.

In 1915, the Ku Klux Klan was revived near Atlanta, Georgia, by Colonel William J. Simmons, a preacher and promoter of fraternal orders who had been inspired by Thomas Dixon’s book The Clansman in 1905 and D.W. Griffith’s film The Birth of a Nation, which mythologized the founding of the first Klan, in 1915. The new organization remained small until Edward Y. Clarke and Elizabeth Tyler brought to it their talents as publicity agents and fundraisers. The revived Klan was fueled partly by patriotism and a romantic nostalgia for the old South. It also expressed the defensive reaction of white Protestants in rural America who felt threatened by the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and the large-scale immigration of the previous decades that had changed the ethnic character of American society.

In addition to the group’s anti-Black ideological core, this second iteration of the Klan also opposed Catholic and Jewish religions, foreigners, and organized labor. It often took a pro-prohibition and pro-compulsory public education stance. Flourishing in the southern and northern states, a growing fear of communism and immigration broadened the Klan’s base, with a particular stronghold in Indiana. This group was the first to use cross burnings and white hooded robes, participating in marches and parades.

As the Klan grew, it attracted the attention of the young Federal Bureau of Investigation. Created just a few years earlier — in July 1908 — the FBI had few federal laws to combat the KKK. However, under its general domestic security responsibilities, the Bureau was able to start gathering information and intelligence on the Klan and its activities. Wherever possible, it looked for federal violations and shared information with state and local law enforcement for its cases.

The 1920s was a lawless decade — an age of highly violent and well-heeled gangsters and racketeers who fueled a growing underworld of crime and corruption. Al Capone and his archrival Bugs Moran had formed powerful, warring criminal enterprises that ruled the streets of Chicago, Illinois, while the early Mafia was crystallizing in New York and other cities, running various gambling, bootlegging, and other illegal operations.

Beginning in 1921, the Klan adopted a modern business system of using full-time, paid recruiters, and it appealed to new members as a fraternal organization, of which many examples were flourishing at the time. Within the first six months of the Association’s national recruitment campaign, Klan membership increased by 85,000. At its peak in the mid-1920s, the organization’s membership ranged from three to eight million.

The national headquarters profited through a monopoly on costume sales, while the organizers were paid through initiation fees. It grew rapidly nationwide at a time of prosperity. Reflecting the social tensions pitting urban versus rural America, it spread to every state and was prominent in many cities.

The crimes committed in the name of its bigoted beliefs were despicable — hangings, floggings, mutilations, tarring and featherings, kidnappings, brandings by acid, and a new intimidation tactic, cross-burnings. The Klan had become a clear threat to public safety and order.

By 1925, when its followers staged a march in Washington, D.C., the Klan had as many as four million members and, in some states, considerable political power. However, sex scandals, internal battles over power, and newspaper exposés quickly reduced the group’s influence.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the Klan’s membership dropped drastically, and the last remnants of the organization temporarily disbanded in 1944. For the next 20 years, the Klan was dormant.

During the 1950s and 1960s, it had a resurgence in some Southern states, especially as civil rights workers attempted to force Southern communities’ compliance with the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Klan often forged alliances with Southern police departments, as in Birmingham, Alabama, or with governor’s offices, as with George Wallace of Alabama. Several members of Klan groups were convicted of murder in the deaths of civil rights workers in Mississippi in 1964 and of children in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham in 1963.

There were numerous instances of bombings, whippings, and murders in Southern communities, carried out in secret but the work of Klansmen. These included four young African American girls killed in 1963 while preparing for Sunday services at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, and the 1964 murder of civil rights workers Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner in Mississippi.

Congress launched an investigation into the KKK in early 1964 following the assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dallas, Texas. According to an FBI report published in May 1965, the KKK was divided into 14 different organizations, with a total membership of approximately 9,000.

President Lyndon B. Johnson publicly denounced the organization in a nationwide television address announcing the arrest of four Klansmen in connection with the slaying of a white female civil rights worker in Alabama.

Throughout the second and third eras of the Klan, many Black Americans left Southern states in the Great Migration. While those who moved North were seeking economic prosperity and social opportunities, they also hoped to escape the racial terror centered around the Klan’s ideological stronghold in the South. With over six million Black Americans participating in this migration, the country’s demographics shifted dramatically.

With the conclusion of the Vietnam War in 1975 and the subsequent return of American soldiers, several key figures arose within the Klan. Upon returning from Vietnam, Louis Beam joined the Alabama-based United Klans of America. His teachings on “leaderless resistance” and early adaptation to technological advances helped bridge neo-Nazi and Klan groups into the organized white power movement. Similarly, David Duke — founder of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in 1975 — maintained a distinctly antisemitic hatred that closed ideological gaps with neo-Nazis.

In 1991, former Ku Klux Klan grand wizard David Duke ran for governor of Louisiana. He finished ahead of incumbent Governor Buddy Roemer in the gubernatorial primary election, a stunning upset that garnered international attention. The possibility that a former grand wizard might be elected governor created a media firestorm and made the 1991 Louisiana gubernatorial election the most closely watched in the country. Duke’s campaign lost steam when advocacy groups such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and major corporations threatened to respond to a Duke victory by mounting an economic boycott of Louisiana, whose economy depended on tourism. As a result, former governor Edwin Edwards defeated Duke by a margin of 61% to 39%, though Duke won slightly over 50% of the white vote.

Despite the persistence of racism, the Klan largely failed to stem the growth of racial tolerance in the South in the late 20th century. Though the organization continued some of its covert activities into the early 21st century, cases of Klan violence became more isolated, and its membership declined to a few thousand. The Klan became a chronically fragmented mixture of several separate and competing groups, some of which occasionally entered into alliances with neo-Nazi and other right-wing extremist groups, as was the case at a demonstration in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017 that erupted in violence resulting in the death of a counterdemonstrator.

In April 1997, FBI agents arrested four members of the True Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in Dallas, Texas, for conspiracy to commit robbery and for conspiring to blow up a natural gas processing plant.

In 1999, Charleston, South Carolina’s city council passed a resolution declaring the Klan a terrorist organization.

Through a series of court cases aimed at bankrupting the Klan and closing the group’s paramilitary training camps, the organization was significantly weakened. Internal fighting and government infiltrations led to a seemingly endless series of splits, resulting in smaller, less organized Klan chapters. Given the Klan’s insistence on remaining an “invisible empire,” it is nearly impossible to estimate how many active members there are today. However, it is fair to assume that the infighting, rigid traditions, and uncouth image of the Klan are not attracting significant new membership.

The Southern Poverty Law Center reported that between 2016 and 2019, the number of Klan groups in America dropped from 130 to just 51.

On July 9, 2020, Tennessee’s State Capitol Commission voted to remove the bust of Nathan Bedford Forrest from the state capitol building. It was subsequently removed on July 23, 2021, and placed in the Tennessee State Museum.

The United States government still considers the Klan a “subversive terrorist organization.”

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

African Americans – From Slavery to Equality

African American History in the United States

The Battle of Athens: An Obscure American Revolution

Terrorism in the United States

Sources:

Encyclopedia Britannica

Federal Bureau of Investigation

SPLC

Wikipedia