El Presidio Real de San Diego is a historic fort in San Diego, California. Today, it commemorates the beginning of the mission effort and European settlement in California and on the Pacific Coast.

San Diego Presidio was established on May 14, 1769, by Gaspar de Portola, leader of the first European land exploration of Alta California — at that time an unexplored northwestern frontier area of New Spain. The Presidio was the first permanent European settlement on the Pacific Coast and was the base of operations for the Spanish colonization of California. The associated Mission San Diego de Alcala later moved a few miles away.

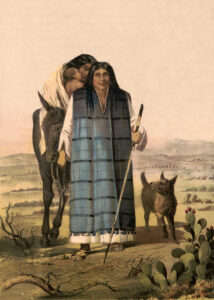

Before the Spanish occupation, the site was home to the Kumeyaay people.

The first Europeans to explore the San Diego Bay area were members of the maritime expedition led by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in 1542. Sebastian Vizcaíno visited in 1602.

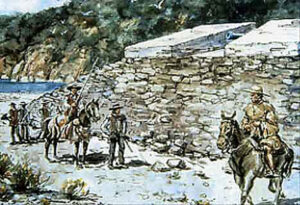

No settlement was made until the fort was begun in May 1769, after nearly 300 Spanish colonists had set out with Father Junípero Serra on an expedition to bring Christianity to the native people of Alta California. On July 1, 1769, Father Junipero Serra said mass before 126 people, survivors of the 300 who had set out initially for Upper California, and Governor Don Caspar de Portola ceremoniously took formal possession of California for Spain. On July 16, 1769, Father Serra founded the first mission in Upper California, Mission San Diego de Alcala, on Presidio Hill. The Presidio was made and constructed entirely of wood. The fenced stockade was made of rough wooden houses with tule roofs, and included two bronze cannons pointing to the bay and the nearby Indian village. It had a commanding view of San Diego Bay and the Pacific Ocean, allowing the Spanish to see potential intruders.

Native Americans vastly outnumbered the small group of colonists in the area – 5,000-some tribes-people who were not universally accepting of the new European presence on their land. In August of 1769, less than a month after the mission was established, a Kumeyaay Indian uprising occurred, in which four Spaniards were wounded, and a boy was killed. Following the Indian attack on the 40 settlers, a crude stockade was erected on Presidio Hill to protect the mission and colony. After the attack, the Spaniards built a stockade on Presidio Hill to protect the mission and colony.

While the new Presidio protected the colonists, its construction also drained the community of its resources. By January 1770, the settlement was at the point of starvation, but on March 19, when all hope seemed lost, a supply ship from Mexico sailed into the bay and saved the California venture from total ruin.

The commandant’s residence was located in the center of the Presidio. On the square’s east side were a chapel, a cemetery, and storehouses; on the south were the gate and guardhouse, and the officers’ and soldiers’ quarters were arranged around the other two sides. In the following years, San Diego Presidio was the base of operations from which expeditions were led to explore new routes and found new missions and presidios.

In 1773 and 1774, adobe structures were built to replace the temporary wood and brush huts. Later, in 1774, the mission was moved six miles northeast in Mission Valley to separate the Kumeyaay from the unwholesome influence of the presidial garrison and obtain a better water supply.

In 1778, the original wooden walls and buildings of the Presidio began to be replaced with adobe structures.

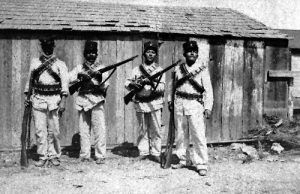

By 1783, 54 troops were stationed at the Presidio.

In 1790, its garrison comprised 51 men, of whom 28 garrisoned the fort, six guarded each of the three missions in the presidio district, and four more were stationed at the pueblo of Los Angeles. About 100 people, including the soldiers, lived within the presidio walls.

When Captain George Vancouver reached San Diego in 1793, on the first foreign ship to visit the city, he was not very impressed from a military standpoint. He reported:

“The Presidio of St. Diego seemed to be the least of the Spanish establishments. It is irregularly built on very uneven ground, which makes it liable to some inconveniences, without the obvious appearance of any object when selecting a spot. With little difficulty, it might be rendered a place of considerable strength by establishing a small force at the entrance of the port, where at this time, there were neither works, guns, houses, or other habitations nearer than the Presidio, five miles from the port, and where they have only three small pieces of brass cannon.”

His visit, along with others, stimulated the Spanish to strengthen it.

In 1795-96, the Presidio was expanded with an esplanade, powder magazine, flagpole, and several houses for soldiers. The first harbor defenses were also erected in 1797, when Fort Guijarros, which included an adobe magazine, barracks, and battery designed to mount ten cannons, was built on Point Loma.

In 1799, 31 men were added to the garrison, raising the total to about 90 soldiers.

In 1810, the force numbered about 100 men, of whom 25 were detached to protect the four missions in the district, and 20 were stationed at the Los Angeles pueblo.

By 1817, the Presidio buildings were reported to be in a “ruinous” condition and needing repair.

Spain maintained the garrison at this level until 1819 when some 50 cavalrymen were added to the force of about 100 soldiers. That year, the total white population of the San Diego District was about 450, and the Indian neophytes numbered about 5,200.

With Mexican independence in 1821, the Presidio came under Mexican control and was officially relinquished by the Spanish on April 20, 1822. From 1825 to 1829, it served as the Mexican governor’s residence. In 1826, it was noted again that the Presidio still needed repair.

Under the Mexican Government, about 120 men comprised the San Diego Presidio force in 1830, of whom 100 lived there. The total district population also included 520 Mexicans and 5,200 Christian Indians. After 1830, however, the San Diego Presidio military force \declined rapidly. By 1835, only 27 soldiers were on duty, 12 at the Presidio and 13 at two missions. The Presidio was abandoned in 1835 and fell into ruins because settlers preferred to live in Old Town, which had developed at the foot of Presidio Hill. Fort Guijarros was also in ruins by 1835; of its seven cannons, only two were serviceable.

Visiting in 1836, Richard Henry Dana, an American writer and lawyer, noted:

“The first place we went to was the old ruinous Presidio, which stands on a rising ground near the village [Old Town], which it overlooks. It is built in the form of an open square, like all the other presidios, and was in a most ruinous state, with the exception of one side, in which the commandant lived with his family. There were only two guns; one spiked, and the other had no carriage. Twelve, half-clothed, and half-starved looking fellows composed the garrison, and they, it was said, had not a musket apiece.”

The last of the Presidio troops was sent north in 1837, and the San Diego Presidio was abandoned entirely as a military post. By 1839, it was reduced to ruins, no structures were left standing, and much stone and adobe had been removed to erect houses in the new pueblo of San Diego.

At the turn of the century, weeds and ice plants covered the Presidio, which had fallen into ruin. Broken red tiles were scattered there, and the foundations of adobe walls were still visible.

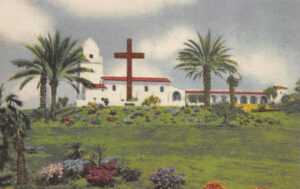

In 1907, George Marston, a wealthy department store owner, bought Presidio Hill with an interest in preserving the site. Unable to attract public funding, Marston built a private park in 1925 with the help of architect John Nolen. He donated about 37 acres to the City of San Diego for park purposes in 1929 and funded the Junípero Serra Museum, designed by William Templeton Johnson. He built the Spanish Revival style architecture in 1928-1929 to house and showcase the San Diego Historical Society collection. Serra Museum is sometimes incorrectly referred to as the Presidio, but nothing remains of the original Presidio. Marston donated the park and museum to the city in 1929.

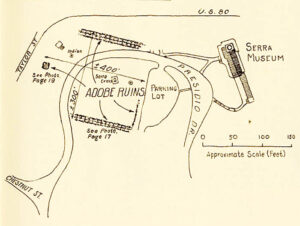

Although accurate information on the Presidio’s appearance was difficult to find, excavations were made on the west side of the church within the old ruins. It was clear that reconstructing the Presidio would be very expensive. Therefore, the ruins were indicated by an adobe wall, protected by mounds of earth placed over them, and planted with grass. A cross was made at the site from broken tiles from the Presidio. The San Diego Presidio’s former site is now in front of the Serra Museum.

Construction of the San Diego River dike and the Mission Valley Road destroyed part of the presidio site, and another section lies beneath a park road. However, some vestiges of the structures that once formed the Presidio remain in grass-covered mounds, suggesting part of the outline of former walls and buildings.

The city of San Diego still owns Presidio Park; the San Diego History Center manages the Serra Museum.

Today, the site of the original Presidio lies on a hill within present-day Presidio Park, although no historic structures remain above ground. The San Diego Presidio was declared a National Historic Landmark in October 1960.

The Serra Museum in Presidio Park marks the original site of the Presidio and Mission. The Presidio site is occasionally used for archaeological excavations.

The Presidio is located at 2811 Jackson St in San Diego, California.

Compiled Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, March 2024.

Also See:

Spanish Missions in California

Missions & Presidios of the United States

Spanish Missions & Presidios Photo Gallery

Spanish Missions Architecture and Preservation

Sources:

National Park Service – Books

National Park Service – Latino Heritage

National Park Service – Travel

National Register of Historic Places

Wikipedia