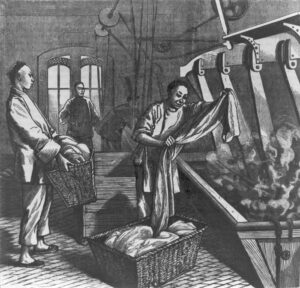

In the 1850s, Chinese workers migrated to the United States, first to work in the gold mines and take agricultural jobs and factory work, especially in the garment industry. Chinese immigrants were particularly instrumental in building railroads in the American West. As Chinese laborers grew successful in the United States, many became entrepreneurs in their own right. As the number of Chinese laborers increased, so did the strength of anti-Chinese sentiment among other workers in the American economy. This finally resulted in legislation that aimed to limit the future immigration of Chinese workers to the United States and threatened to sour diplomatic relations between the United States and China.

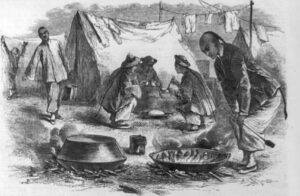

Harper’s Weekly – Chinese Immigrants 1876.

American objections to Chinese immigration took many forms and stemmed from economic and cultural tensions and ethnic discrimination. Most Chinese laborers who came to the United States did so to send money back to China to support their families. At the same time, they also had to repay loans to the Chinese merchants who paid for their passage to America. These financial pressures left them little choice but to work for whatever wages they could. Non-Chinese laborers often required much higher wages to support their wives and children in the United States. They also generally had a stronger political standing to bargain for higher wages. Therefore many non-Chinese workers in the United States came to resent the Chinese laborers, who might squeeze them out of their jobs.

As with most immigrant communities, many Chinese settled in their neighborhoods, and tales spread of Chinatowns where many Chinese men congregated to visit prostitutes, smoke opium, or gamble. Some anti-Chinese legislation advocates argued that admitting Chinese into the United States lowered American society’s cultural and moral standards. Others used a more overtly racist argument for limiting immigration from East Asia and expressed concern about the integrity of American racial composition.

Even as they struggled to find work, Chinese immigrants also fought for their lives. During their first few decades in the United States, they endured an epidemic of violent racist attacks, a campaign of persecution and murder that today seems shocking. From Seattle to Los Angeles, from Wyoming to the small towns of California, immigrants from China were forced out of business, run out of town, beaten, tortured, lynched, and massacred, usually with little hope of help from the law. Racial hatred, an uncertain economy, and a weak government in the new territories all contributed to this climate of terror and bloodshed. The perpetrators of these crimes, which included Americans from many segments of society, largely went unpunished. Exact statistics for this period are difficult to come by, but a case can be made that Chinese immigrants suffered worse treatment than any other group that came voluntarily to the U.S.

To address these rising social tensions, from the 1850s through the 1870s, the California state government passed a series of measures aimed at Chinese residents, ranging from requiring special licenses for Chinese businesses or workers to preventing naturalization. Because anti-Chinese discrimination and efforts to stop Chinese immigration violated the 1868 Burlingame-Seward Treaty with China, the federal government negated much of this legislation.

In 1879, advocates of immigration restriction succeeded in introducing and passing legislation in Congress to limit the number of Chinese arriving to 15 per ship or vessel. Republican President Rutherford B. Hayes vetoed the bill because it violated U.S. treaty agreements with China. Nevertheless, it was still a significant victory for advocates of exclusion. Democrats, led by supporters in the West, advocated for the all-out exclusion of Chinese immigrants. Although Republicans were mainly sympathetic to western concerns, they were committed to a platform of unrestricted immigration. To appease the western states without offending China, President Hayes sought a revision of the Burlingame-Seward Treaty in which China agreed to limit immigration to the United States.

In 1880, the Hayes Administration appointed U.S. diplomat James B. Angell to negotiate a new treaty with China. The resulting Angell Treaty permitted the United States to restrict, but not entirely prohibit, Chinese immigration. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which, per the terms of the Angell Treaty, suspended the immigration of Chinese laborers (skilled or unskilled) for ten years. This act was the first significant restriction on free immigration in U.S. history, and it excluded Chinese laborers from the country under penalty of imprisonment and deportation. It also made Chinese immigrants permanent aliens by excluding them from U.S. citizenship. Chinese immigrants in the U.S. now had little chance of ever reuniting with their families or of starting families in their new home. The Act also required every Chinese person traveling in or out of the country to carry a certificate identifying their status as a laborer, scholar, diplomat, or merchant.

For American presidents and Congressmen addressing the question of Chinese exclusion, the challenge was balancing domestic attitudes and politics, which dictated an anti-Chinese policy, while maintaining good diplomatic relations with China, where exclusion would be seen as an affront, a violation of treaty promises. The domestic factors ultimately trumped international concerns. In 1888, Congress took exclusion even further and passed the Scott Act, which made reentry to the United States after a visit to China impossible, even for long-term legal residents. The Chinese Government considered this act a direct insult but could not prevent its passage. In 1892, Congress voted to renew exclusion for ten years in the Geary Act. In 1902, the prohibition was expanded to cover Hawaii and the Philippines, all over strong objections from the Chinese Government and people. Congress later extended the Exclusion Act indefinitely.

In China, merchants responded to the humiliation of the exclusion acts by organizing an anti-American boycott in 1905. Though the Chinese government did not sanction the movement, it received unofficial support in the early months. President Theodore Roosevelt recognized the boycott as a direct response to the unfair American treatment of Chinese immigrants. Still, with American prestige at stake, he called for the Chinese government to suppress it. After five difficult months, Chinese merchants lost the impetus for the movement, and the boycott ended quietly.

In the first decades of the 20th century, Chinese immigrants continued to work toward greater inclusion in American life. Although the Exclusion Act was still in effect, the law did permit Chinese merchants, diplomats, and students to enter the country. For a time, these immigrants were even allowed to bring their wives and families. To take advantage of this loophole, young people often came into the U.S. by posing as family members of those with merchant status; these counterfeit family members became known as “paper sons” and “paper daughters.”

Despite all the legal and practical obstacles, between 1910 and 1940, some 175,000 Chinese immigrants passed through Angel Island Immigration Station near San Francisco. At the same time, the growing number of children born to Chinese Americans helped add to the community’s sense of permanence and stability. Since any child born in America automatically became a U.S. citizen, many parents bought property in their children’s names and were thus able to start businesses and make investments that would otherwise not have been available to them.

As more immigrants found professional work and achieved financial success, they began to move out of urban Chinatowns, often to new suburbs or other outlying neighborhoods. Despite continuing restrictions on immigration, the Chinese population of the U.S., which had dropped from about 107,000 in 1890 to a low of 61,000 in 1920, began to rise again.

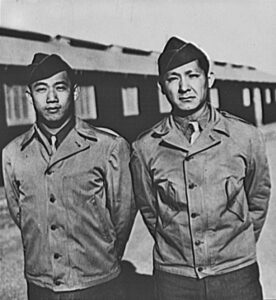

The outbreak of World War II brought Chinese immigrants and their descendants even further into the mainstream of U.S. society. Japan’s brutal invasion of China led to greater public sympathy for the Chinese people. It prompted Chinese Americans to register for the draft, join war industries, and enlist in record numbers. San Francisco’s Chinatown even built and funded its own pilot-training school to prepare Chinese American pilots to fight the Japanese air force. Almost half of the 13,000 Chinese American soldiers who served during the war were not U.S. citizens, still barred by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

In 1943, the Exclusion Act was finally repealed, brought down by the pressures of wartime labor shortages and popular sentiment. Under the new legislation, Chinese immigrants were finally made eligible for citizenship, and new quotas were set for immigration. Even greater changes came two years later when the War Bride Act and the G.I. Fiancées Act permitted Chinese Americans to bring their wives into the country. Family life, for centuries one of the most cherished aspects of Chinese culture, was finally possible for the Chinese community in the United States.

By the end of the 1960s, the Chinese American community had been transformed. After long decades of slow growth under tight constraints, Chinese immigration expanded and changed dramatically.

A new immigration law passed in the mid-60s changed how the U.S. counted its immigrant population. This law, the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, allowed far more skilled workers and family members to enter the country than ever before and eliminated the old quota system that gave preference to western Europeans. As a result, the Chinese American population in the U.S. almost doubled within ten years.

With the new surge of growth, the community changed. This new group of immigrants did not come from the same rural provinces of China as the immigrants of the 1800s and early 1900s. Instead, many came from urban Hong Kong and Taiwan. They had a different outlook on life than the earlier immigrants, who had created slow-paced, close-knit communities. The Hong Kong and Taiwan immigrants had more exposure to urban fashion and music and had greater expectations of social mobility. In the 1980s, many more people from China, including university students, joined the migration to the U.S. As immigration from Taiwan, China, and Hong Kong continue, the Chinese American communities in both large cities and suburbs continue to adapt to the challenges of a growing and diverse culture.

Compiled & edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023. Source: Office of the Historian