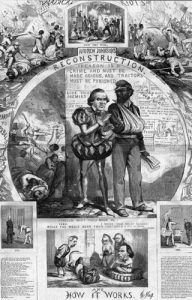

Reconstruction of the southern states followed the Civil War from 1865 to 1877, during which time attempts were made to make the newly freed slaves citizens with civil rights and transform the 11 former Confederate states so that they could be readmitted to the Union.

A few hours after President Abraham Lincoln’s death, Andrew Johnson of Tennessee took the oath of office as President of the United States on April 15, 1865. Johnson had been given the second place on the Republican ticket in 1864, partly to reward him for his fidelity to the Union cause in the seceding state of Tennessee and to save the Republican Party from the reproach of being called “sectional” in again choosing both its candidates from Northern states, as it had done in 1856 and 1860.

But, the selection of Johnson was most unfortunate. Many would say that he was coarse, violent, egotistical, obstinate, and vindictive, and of Lincoln’s splendid array of statesman-like virtues, he possessed only two: honesty and patriotism. Most would agree that he would display political ineptitude and an astonishing indifference toward the plight of the newly freed African Americans over the next few years. Unfortunately, his lack of tact, wisdom, and deference to the opinions of others were lacking at a time when they were sorely needed.

Armed resistance in the South was at an end. But the great question remained of how the North should use its victory. Except for a momentary wave of desire to avenge Lincoln’s murder by the execution of prominent “rebels,” there was no thought of inflicting the extreme punishment of traitors on the Southern leaders. Still, there was the complex problem of restoring the states of the secession to their former place in the Union.

What was their condition? Were they still states of the Union despite their four-year struggle to break away from it? Or, had they lost states’ rights and became territories of the United States, subject to such governments as the authorities at Washington might have provided? Or, was the South merely a “conquered province,” which had forfeited by its rebellion even the right of protection by the national government and which might be made to submit to such terms as the conquering North saw fit to impose?

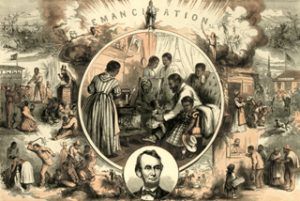

Long before the close of the war, President Abraham Lincoln had answered these questions according to the theory he had held consistently from the day of the assault on Fort Sumter, South Carolina; namely, that not the states themselves, but combinations of individuals in the states, too powerful to be dealt with by the ordinary process of the courts, had resisted the authority of the United States. Therefore, he welcomed and nursed every manifestation of loyalty in the Southern states. He had recognized the representatives of the small Unionist population of Virginia, assembled at Alexandria within the Federal lines, as the true government of the state. He immediately established a military government in Tennessee on the Union arms’ success in the spring of 1862. By a proclamation in December 1863, he had declared that as soon as 10% of the voters of any of the seceded states should form a loyal government and accept the legislation of Congress on the subject of slavery, he would recognize that government as legal. Such governments had been set up in Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana. However, Lincoln disagreed with Congress regarding the final method of restoring the Southern states to their place in the Union. That question waited until the close of the war, and the awful pity is that Abraham Lincoln was no longer alive when it came.

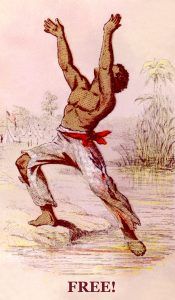

During the summer and autumn of 1865, when Congress was not in session, President Andrew Johnson applied Lincoln’s plan to the states of the South, just as if it had been settled that Congress was to have no part in their Reconstruction. He appointed military governors in North and South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas. He ordered conventions to be held in those states, which repealed the ordinances of secession and framed new constitutions. State officers were elected, and Legislatures were chosen, repudiating the debts incurred during the war (except in South Carolina) and ratifying the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery (except in Mississippi). When Congress met in December 1865, senators and representatives from the Southern states, which, but a few months before, had been in rebellion against the authority of the United States, were waiting at the doors of the Capitol for admission to their seats.

However, Congress had good reasons for not permitting these men to make laws for the Union, which they had so lately fought to destroy. In the first place, President Johnson had presumptuously assumed to himself, during the recess of Congress, the sole right to determine on what terms the seceded states should be restored to the Union. The President had the power of pardon, which he could extend to individuals as widely as he pleased. However, the pardoning power did not give him the right to determine the states’ political condition, which had made war against the Union.

Furthermore, the conduct of the Johnson administration in the autumn of 1865 was offensive to the North. Although the South accepted the 13th Amendment, they passed very harsh laws against the freed slaves, which in some cases came very near to reducing them to the condition of slavery again. For example, “vagrancy” laws imposed a fine on any blacks wandering about without a permanent home, and if a white man were to pay their fine, he could then compel him to work out his debt.

“Apprentice” laws assigned young African-Americans to “guardians,” who were often their former owners, and dictated that they should work without wages in return for their board and clothing. To the Southerners, these laws seemed to be only the necessary protection of the white population against the deeds of crime and violence to which a large, wandering, unemployed body of blacks might be tempted. Nearly 4,000,000 slaves had been suddenly liberated. Very few of them had any means for beginning a life of industrial freedom, and many thought that miraculous prosperity was to be bestowed upon them without their effort, such as the plantations of their late masters being up among them. Unfortunately, many low-minded, broken-down politicians who came from the North and posed as their guides and protectors often encouraged these ideas. They poisoned their minds against the only people who could help them begin their new life of freedom- their old masters.

The people of the North, who had little or no realization of the tremendous social problem that the liberation of 4,000,000 freed slaves brought upon the South, regarded the “black codes” of the Johnson administration of 1865, which forbade the blacks such freedom of speech, employment, assembly, and migration as they had, as a proof of the defiant purpose of the South, to thrust the blacks back into their old positions of slavery. Therefore, the North determined that the Southern states should not be restored to their place in the Union until they gave better proof of an honest purpose to carry out the Thirteenth Amendment. The war for the abolition of slavery, which had divided the Union, had been too costly in men and money to allow its results to be jeopardized by the legislation of the Southern states.

A further offense in the eyes of the North was the sort of men whom the Southern states sent up to Washington in the winter of 1865 to take their places in Congress.

They were primarily prominent secessionists. Some had served as members of the Confederate Congress at Richmond, some as brigadier generals in the Confederate Army. Alexander Stephens, who had served as vice president of the Confederate, was sent by the legislature of Georgia to serve in the United States Senate. To the Southerners, sending their best talent to Congress seemed perfectly natural. They would have searched in vain to find politicians who had not been active in the Confederate cause. But, to the North, the appearance of these men in Washington seemed a piece of defiance and bravado on the part of the South, a boast that they had nothing to repent of and that they had forfeited no privilege of leadership.

Then, finally, there was a political reason why the Republican Congress assembled in December 1865 should not admit the men sent to it. These men were almost all Democrats and as hostile to the “Black Republican” party as they had been in 1856 and 1860. Combined with the Democrats and “copperheads” of the North, who had opposed the war, they might prove numerous enough to oust the Republicans from power. The party that had saved the country must rule, it said the Republican orators.

Moved by these reasons, Congress, instead of admitting the Southern members, appointed a committee of 15 men to investigate the condition of the late seceded states and recommend on what terms they should be restored to their full privileges in the Union. Naturally, Johnson was offended that Congress should ignore or undo his work, and he immediately assumed a tone of hostility to the leaders of Congress. He was course when making a speech from the balcony of the White House in January 1866 to attack Charles Sumner, Thaddeus Stevens, and Wendell Phillips by name, accusing them of seeking to destroy the rights of the Southern states and to rob the President of his legal powers under the Constitution, and even to encourage his assassination. In the early months of 1866, when Congress passed bills to protect the blacks against the hostile legislation of the Southern states, Johnson vetoed the bills. But, Congress was strong enough to pass them over his veto. The battle was then somewhat joined between the President and Congress, boding ill for the prospects of peace and order in the South.

On April 30, 1866, the committee of 15 reported. It recommended a new amendment to the Constitution (the 14th Amendment), which should guarantee the civil rights of the black citizens of the South, reduce the representation in Congress of any state that refused to let them vote and disqualify the leaders of the Confederacy from holding federal or state office. This last provision, which deprived the Southern leaders of their political rights, assumed that these men were not reconciled to the Union. But, the rest of the Fourteenth Amendment was a fair basis for the Reconstruction of the Southern states. Congress passed the Amendment on June 13, 1866, and Secretary of State William Seward sent it to the states for ratification.

While Congress did not explicitly promise that it would admit the representatives and senators of the states that ratified the 14th Amendment, it doubtlessly would have done so. For, when Tennessee ratified it in July 1866, that state was promptly restored to its full privileges in the Union. The other states of the secession might well have followed the lead of Tennessee, but every one of them, indignant at the disqualifying clause, overwhelmingly rejected the Amendment. It thus failed to secure the votes of three-fourths of the states of the Union necessary for its ratification.

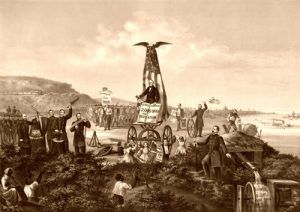

Congress, angered by this conduct on the part of the South, decided to take the Reconstruction of the states of the secession entirely into its own hands. The elections of 1866, which had taken place while the 14th Amendment was before the people, had resulted in an overwhelming victory for the congressional party of Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner over the President’s supporters. President Johnson himself had contributed to the defeat of his policies by encouraging the Southern states to reject the 14th Amendment and by making a series of outrageous speeches in the West during the autumn of 1866, vilifying the congressional leaders and exalting his patriotism and judgment.

Then, early in 1867, Congress devised a thorough plan for reconstructing the South under the leadership of Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania in the House and of Sumner and Henry Wilson of Massachusetts in the Senate.

By the Reconstruction Act of March 2, 1867, the entire area occupied by the ten states that had rejected the 14th Amendment was divided into five military districts. A prominent general of the Union Army was put in command of each district. The Johnson administration governments of 1865 were swept away, and in their place, new governments were established under the supervision of the major generals and their detachments of United States troops.

The Reconstruction Act further provided that blacks should be allowed to participate in framing the new constitutions and running the new governments. At the same time, their former masters were, in large numbers, disqualified. The act also provided that when the new state governments ratified the 14th Amendment and the Amendment became part of the Constitution of the United States, these states could be restored to their place in the Union.

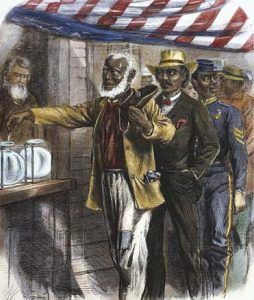

Freedmen voting in New Orleans, Louisiana, 1867.

Thus, by the Reconstruction Act of 1867, Congress literately forced African-American suffrage on the South at the point of the bayonet. It was a violent measure for Congress to adopt, even though the conduct of the states of the secession in rejecting the 14th Amendment was sorely provoking. The blacks outnumbered the whites in the states of South Carolina, Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi, and the South particularly resented the fact that blacks in the North were allowed to vote in only six states, where they counted as the tiniest fraction of the population. Ohio, in the very year Congress was forcing African-American voting in the South (1867), rejected by over 50,000 votes the proposition to give the ballot to the few blacks of that state. Conceding that Congress had the right to impose black suffrage on the South as a conqueror’s privilege, it was nevertheless a most unwise thing to do at the time. Resentment was extremely high as the people of the South felt that Congress was setting up freed slaves to be in power over their former masters, which did not ensure the protection of black rights or the stability and peace of the Southern governments.

The governments of North and South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas, formed under the military domination of the Reconstruction Acts, were very inefficient. Without education or experience, African Americans were suddenly thrust into positions of high political office. Others in office included carpetbaggers, a negative term Southerners gave to those who moved to the South during the Reconstruction era. Many relocated northerners were motivated by questionable objectives, including buying up plantations at highly reduced prices.

Other government members included southern whites who supported Reconstruction, called scalawags. Prompted by their unscrupulous carpetbagger friends and scalawag backers, the African-American members could be counted on to vote for the Republican ticket, which was enough for most of the advocates of Reconstruction. The Carpetbaggers and Scalawags were said to have politically manipulated and controlled former Confederate states for their own financial and power gains for varying periods.

But, for the exhausted Southern states, already amply “punished” by the desolation of war, the rule of these initial governments of 1868 was an indescribable state of extravagance, fraud, and incompetence, — a travesty on government. Instead of wise, conservative legislatures, which would encourage industry, keep down expenditures, and build up the shattered resources of the South, there were ignorant groups of men in the state capitals, dominated by corrupt politicians, who plunged the states further and further into debt by voting themselves enormous salaries, and by spending lavish sums of money on railroads, canals, and public buildings and works, for which they reaped hundreds of thousands of dollars in kickbacks.

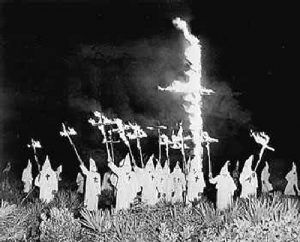

Such governments could not, of course, last unless supported by Northern bayonets, and the Republican carpetbag politicians in the South were not slow to call upon the Republican administration at Washington for detachments of troops whenever their supremacy was threatened. Deprived by force of any legal means of defense against this reprehensible government, the South resorted to intimidation and persecution of the blacks. Secret organizations called the Ku Klux Klan, made up mostly of young men, took advantage of the black man’s superstitious nature to force him back into the humble social position he held before the war. The members of the Ku Klux on horseback, with man and horse, robed in ghostly white sheets, spread terror at night through African-American quarters and posted on trees and fences horrible warnings to the carpetbaggers and scalawags to leave the country soon if they wished to live.

Inevitably, violence was done in this reign of terror inaugurated by the Ku Klux Klan. Blacks were beaten, scalawags were shot, and the Carpetbag officials greatly exaggerated these first violent events, asking for more troops for their protection. It came to actual fighting in the streets of New Orleans, Louisiana, and the trenches outside Vicksburg, Mississippi, which were used in 1863 by the Union sharpshooters, were the scene, ten years later, of a disgraceful race conflict between blacks and whites. Thus, long after the war was over, the South, which should have been well on the way to industrial and commercial recovery under the leadership of its own best genius, still presented in many parts a spectacle of anarchy, violence, and fraud, — its legislatures and offices in the grasp of low political adventurers, its resources squandered or stolen, its people divided into two bitterly hostile races.

Instead of keeping a firm military hand upon the southern states and waiting for them to comply with the terms offered in the 14th Amendment, the Republican Congress of 1867, by hastening to reconstruct them based on Black suffrage, did them an unpardonable injury. Though some bitterness would have, no doubt, existed in the South against their fellow countrymen of the North, due to the Civil War itself, it was made much worse and lasted much longer for the “crime of Reconstruction.”

Recovery of a Nation

Although the restitution of the Southern states to their place in the Union was the most pressing business of Congress in the years immediately following the Civil War, it was by no means the only problem in the Reconstruction of the nation.

During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln exercised greater power than any other President in our history up until this time. As Commander-in-Chief of the army and navy, he had the appointment of officers and the general direction of campaigns. Through his Secretaries of War and the Treasury, he had superintended the raising of men and money to prosecute the war. As measures of safety and military policy, he had suspended the clauses of the Constitution (Amendments V and VI) which guarded citizens of the United States against arbitrary arrest and punishment without a jury trial and had emancipated all the slaves of men in rebellion against the authority of the United States. Congress had generously ratified his acts, but toward the close of the war, it had begun to reassert its power, as was shown by its resistance to Lincoln in the Wade-Davis Bill, the proposed program for the Reconstruction of the South.

Under his successor, Andrew Johnson, the pendulum swung to the other extreme. Congress developed quite as absolute a control over the government as President Lincoln had exercised during the war. Congress not only overrode Johnson’s vetoes with mocking haste, but it passed acts depriving him of his constitutional powers as commander of the army and forbidding him to dismiss a member of his cabinet. Finally, it impeached him on the charge of high crimes and misdemeanors.

On the same day the Reconstruction Act was passed on March 2, 1867, Congress also instituted a law called the Tenure of Office Act, which forbade the President to remove officers of the government without the consent of the Senate and made the tenure of cabinet officers extend through the presidential term for which they were appointed. This was an invasion of the privilege which the President had always enjoyed.

removing his cabinet officers at will. The act aimed to keep Edwin Stanton, who was in thorough sympathy with the radical leaders of Congress, at the head of the Department of War.

However, President Johnson violated the Tenure of Office Act, which he believed unconstitutional, and removed Stanton. As a result, the House of Representatives impeached him on February 24, 1868, and the Senate assembled the following month under the presidency of Chief Justice Chase to try the case. To the chagrin of the radical Republicans, the Senate failed by one vote of the two-thirds majority necessary to convict the President. Johnson finished his term, openly despised and shunned by the Republican leaders, and was succeeded on March 4, 1869, by Ulysses S. Grant.

Though Grant had been known as a superb soldier, he would not earn the same reputation as a statesman. In a visit to the Southern states a few months after the close of the war, he had become convinced, as he wrote, that “the mass of thinking men of the South accepted in good faith” the outcome of the struggle. Yet, as President, he upheld the disgraceful governments of the Reconstruction Act and constantly furnished troops to keep the carpetbag and scalawag officials in power to provide Republican votes for congressmen and presidential electors. He was so simple and direct that he failed to understand the duplicity and fraud practiced under his very nose. Like all untrained men in public positions, he made his likes and dislikes the test of his political judgments, and it was only necessary to win his friendship to have his official support. Unfortunately, his early struggle with poverty and his failure in business had led him to set too high a valuation on mere monetary success, making him unduly susceptible to the influence of men who had made millions. In his treatment of the South, Grant was changed by his radical Republican associates from a generous conqueror into a narrow, partisan dictator.

Though his terms in office would be remembered for their corruptness, he implemented several policies that would increase Civil Rights and decrease violence. He created the Department of Justice and Office of Solicitor General, led by Attorney General Amos Akerman and the first Solicitor General Benjamin Bristow, who both prosecuted thousands of Klan men under the Force Acts. He also sent additional federal troops to nine South Carolina counties to suppress Klan violence in 1871. Additionally, he used military pressure to ensure that African Americans could maintain their new electoral status, endorsed the 15th Amendment, which gave African Americans the right to vote, and signed the Civil Rights Act of 1875, giving people access to public facilities regardless of race.

All of the seceding states were eventually readmitted to the Union and allowed representation in Congress on the following dates:

Tennessee – July 24, 1866

Arkansas – June 22, 1868

Florida – June 25, 1868

North Carolina – July 4, 1868

South Carolina – July 9, 1868

Louisiana – July 9, 1868

Alabama – July 13, 1868

Virginia – January 26, 1870

Mississippi – February 23, 1870

Texas – March 30, 1870

Georgia – July 15, 1870

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.

About This Article: Much of this article is part of the Cyclopedia of American Government, Volume 1, edited by Andrew C. McLaughlin and Albert Bushnell Hart, 1914. However, the article that appears here is far from the original as it has been heavily edited, truncated, and additional information added.

Also See: