The Civil Rights Movement was a struggle for social justice that took place primarily during the 1950s and 1960s for African Americans seeking constitutional equality at the national level. It was the most significant mass movement in modern American history as black demonstrations swept the country. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was rooted in the struggle of African Americans to obtain the fundamental rights of citizenship.

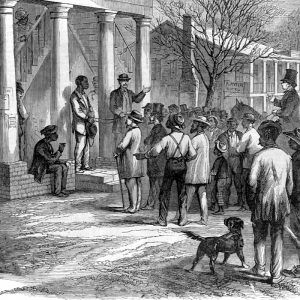

More than a century before, antislavery initiatives had gradually abolished slavery in the Northern states by the 1830s, but free blacks were not accorded full citizenship rights. Slaveholders’ slaveholders’ economic dominance in the South hindered any abolition discussion. Discord between the North and South ultimately led to the Civil War and, finally, to the emancipation of slaves. However, this didn’t end discrimination against blacks — they continued to endure the devastating effects of racism, especially in the South.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Northern Congressional Republicans proposed the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution that granted newly freed slaves freedom, citizenship, and the right to vote. Several civil rights acts were also passed to protect the freedom of former slaves. During Reconstruction, African American men participated in electoral politics as voters and public officials. However, the three constitutional amendments that granted legal status to African Americans were poorly enforced, and members of white supremacist groups, such as the Ku Klux Klan, terrorized black citizens for exercising their right to vote, running for public office, and serving on juries. Congress passed a series of Enforcement Acts in 1870 and 1871 to end such violence, including military force to protect African Americans, but this, too, was a failure.

In 1870, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts introduced a new civil rights bill to give African Americans equal access to such public accommodations as churches, theaters, trains, ships, jury boxes, and public schools. The bill died in committee in 1870 and again in 1871, but Sumner persevered despite failing health. Sumner died on March 11, 1874, and after years of delay, the Civil Rights Bill was finally signed into law in March of 1875. However, the bill was a mere shadow of Sumner’s vision of protection of the rights of blacks and was dealt a major defeat with the Compromise of 1877 when Southern Democrats conceded the closely contested 1876 presidential election to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes in exchange for the withdrawal of federal troops from the South. Blacks, however, continued to attend schools and churches, participate in politics, and exert their rights as citizens as much as possible in the face of growing white resistance and violence.

Despite the legislation and constitutional amendments passed during the era of Reconstruction that extended federal protections to African Americans, many states adopted various methods to disenfranchise black voters. They instituted “Jim Crow” segregation laws mandating the separation of the races in practically every aspect of life. Debt peonage (involuntary servitude of laborers), sharecropping, and tenant farming often reduced blacks to generational poverty.

The Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist organizations engaged in lynchings, beatings, and burnings to enforce the new racial order and to keep African American voters away from the polls or any political activity. Beginning in the 1870s, blacks migrated in increasing numbers from the South to northern and western regions, a phenomenon that would ultimately transform the racial geography of the country.

The U.S. Supreme Court was inclined to agree with these segregation policies and set the stage for even more Jim Crow Laws with several of its decisions. In 1883, the Supreme Court declared the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional and ruled that the 14th Amendment did not prohibit individuals and private organizations from discriminating based on race. In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court’s decision to separate but “equal” accommodations in the Plessy v. Ferguson case, ruling that racial segregation was constitutional. This paved the way for more racial segregation, which continued well into the 20th century.

Afterward, more Jim Crow laws were established. Blacks couldn’t use public facilities as whites, couldn’t live in neighborhoods, or go to the same schools. Interracial marriage was illegal, and most blacks couldn’t vote; they could not pass voter literacy tests. Jim Crow laws weren’t adopted in other states; however, blacks still experienced discrimination at their jobs or when they tried to buy a house or get an education. To make matters worse, laws were passed in some states to limit black voting rights.

In the meantime, violence towards black people continued throughout the nation despite legislation such as the Enforcement Acts. The issue of lynching became particularly explosive in the early 20th century. Senator Robert Wagner of New York and his allies repeatedly attempted to confront such violence through anti-lynching legislation. Still, opponents successfully blocked all such measures, often through the filibuster.

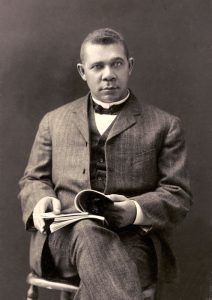

Popular black leader Booker T. Washington advised African Americans to focus on education and economic self-improvement, strategies he deemed necessary to acquire on the road to civil rights in the face of racism. However, as segregation tightened and racial oppression escalated across the United States, some leaders of the African American community began to reject Washington’s approach. W.E.B. Du Bois and other black leaders channeled their activism by founding the Niagara Movement in 1905. Later, they joined white reformers in 1909 to form the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which used the federal courts to challenge disenfranchisement and residential segregation. Job opportunities were the primary focus of the National Urban League, which was established in 1910.

During the Great Migration of 1910-1920, African Americans by the thousands poured into industrial cities in the North to find work and later to fill labor shortages created by World War I. Though they continued to face exclusion and discrimination in employment, as well as some segregation in schools and public accommodations, Northern black men faced fewer barriers to voting. As their numbers increased, their vote became a crucial factor in elections. The war and migration bolstered a heightened self-confidence in African Americans that manifested in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. The NAACP lobbied aggressively for a federal anti-lynching law.

In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt provided more federal support to African Americans than ever since Reconstruction. Even so, New Deal legislation and policies continued to allow considerable discrimination. During the mid-1930s, the NAACP launched a legal campaign against segregation, focusing on inequalities in public education. By 1936, the majority of black voters had abandoned their historic allegiance to the Republican Party and joined with labor unions, farmers, progressives, and other ethnic minorities in assuring President Roosevelt’s laRoosevelt’selection. The election significantly shifted the balance of power in the Democratic Party from its Southern block of white conservatives towards this new coalition.

In the spring of 1941, hundreds of thousands of whites were employed in industries mobilizing for the possible entry of the United States into World War II. At this time, most blacks were low-wage farmers, factory workers, domestics, or servants and were discouraged from joining the military. Black labor leader A. Philip Randolph threatened a mass march on Washington unless blacks were hired equally for those jobs, stating: “It is time to “wake up Washington as it has never been shocked before.” To prevent the march, which many feared would result in race riots and international embarrassment, President Franklin Roosevelt issued an executive order in June 1941 that opened national defense jobs and other government jobs to all Americans regardless of race, creed, color, or national origin. This order also established the Committee on Fair Employment Practices to receive and investigate discrimination complaints and take appropriate steps to redress valid grievances.

Black men and women served heroically in World War II despite suffering segregation and discrimination during their deployment. Yet many were met with prejudice and scorn upon returning home. The fight against fascism during World War II brought to the forefront the contradictions between America’s idealAmerica’scracy and equality, its treatment of racial minorities, and dramatically altered opinions and expectations. African American veterans led a “double victory” campaign, declaring that those who fought to end fascism abroad would not tolerate discrimination at home.

President Harry Truman appointed a special committee to investigate racial conditions that detailed a civil rights agenda in its report. In 1948, Truman issued an executive order that abolished racial discrimination in the military. The NAACP won important Supreme Court victories and mobilized a mass lobby of organizations to press Congress to pass civil rights legislation. These events helped set the stage for grass-roots initiatives to enact racial equality legislation and incite the civil rights movement.

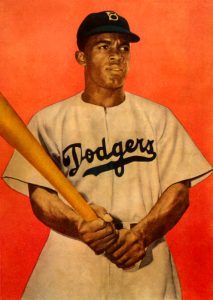

During this time, African Americans achieved notable firsts — Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in major league baseball, and civil rights activists Bayard Rustin and George Houser led black and white riders on a “Journey of Reconciliation” to challenge “racial segregation on interstate buses.

The NAACP’s legal stance against segregated education culminated in the 1954 Supreme Court’s landmaCourt’sn v. Board of Education decision, in which African Americans gained the right to study alongside their white peers in primary and secondary schools. The decision fueled an unwilling and violent resistance in the Southern states, which used various tactics to evade the law.

In the summer of 1955, a surge of violence against blacks included the kidnapping and brutal murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till. This crime provoked widespread and assertive protests from black and white Americans. By December 1955, the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott led by Martin Luther King, Jr. began a protracted campaign of nonviolent civil disobedience to protest segregation that attracted national and international attention. In 1956, a group of Southern senators and congressmen signed the “Southern Manifesto,” vowing resistance to racial integration by all “lawful means.”

Resistance heightened in 1957-1958 during the crisis over the integration at Little Rock, Arkansas’ Central School. In the meantime, President Dwight D. Eisenhower sought to strengthen enforcement mechanisms and sent a civil rights bill to Congress in 1957. The House passed the measure on June 18; later, the Senate approved a scaled-down bill with amendments. Although not as strong as initially proposed, this law created a Commission on Civil Rights, established a civil rights division within the Department of Justice, provided for jury trials in the case of criminal civil rights violations, allowed federal prosecution of anyone who tried to prevent someone from voting and created a commission to investigate voter fraud.

Despite making some gains, blacks still experienced blatant prejudice daily. In February 1960, North Carolina college students staged a sit-in at a Woolworth’s luWoolworth’s in a Greensboro department store that refused to serve them because of their race. Over the next several days, hundreds of people joined their cause. After some were arrested and charged with trespassing, protestors launched a boycott of all segregated lunch counters until the owners caved. The original four students were finally served at the Woolworth’s, where they’d first stood their ground.

Their efforts spearheaded peaceful demonstrations in dozens of cities nationwide as civil rights organizers led demonstrations to protest segregation, discrimination, and voting restrictions. Though these efforts were nonviolent, these protests frequently faced fierce opposition.

Nonviolent direct action increased during the presidency of John F. Kennedy, beginning with the 1961 Freedom Rides, where civil rights activists rode interstate buses into the segregated southern United States.

Hundreds of demonstrations erupted in cities and towns across the nation. National and international media coverage of using fire hoses and attack dogs against child protesters precipitated a crisis in the Kennedy administration, which it could not ignore. The bombings and riots in Birmingham, Alabama, on May 11, 1963, compelled Kennedy to call in federal troops. On June 19, 1963, the president sent Congress a comprehensive civil rights bill.

In August 1963, a coordinated March in Washington, D.C., brought more than 200,000 black and white people to demand “Jobs and Freedom.” The highlight of the march was Martin Luther King’s speech, where he continually stated, “I have a dream”…”

Congress and President John Kennedy responded by introducing legislation in 1963 to deliver on the long-awaited promises of civil and legal protections for all Americans. After the president’s speech on November 22, the fate of Kennedy’s bill was in the hands of his vice president and successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, and the United States Congress.

President Lyndon Johnson made the passage of Kennedy’s civiKennedy’sbill his top priority during the first year of his administration. He enlisted the help of the NAACP, the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, and key members of Congress to secure the bill’s passage on July 2, 1964, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law, which prohibited discrimination in the workplace, public accommodations, public facilities, and agencies receiving federal funds and strengthened prohibitions on school segregation and discrimination in voter registration. It also granted the federal government strong enforcement powers in civil rights, continued the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, and established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

On March 7, 1965, the civil rights movement in Alabama took an especially violent turn as 600 peaceful demonstrators participated in the Selma to Montgomery march to protest the killing of a black civil rights activist by a white police officer and encourage legislation to enforce the 15th Amendment. As they neared the Edmund Pettus Bridge, they were blocked by Alabama state and local police. Refusing to stand down, protestors moved forward and were viciously beaten and teargassed by police, and dozens of protestors were hospitalized. The entire incident was televised and became known as “Bloody Sunday.” Some activists wanted to retaliate violently, but Dr. Martin Luther King pushed for nonviolent protests and eventually gained federal protection for another march.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act of 1968 expanded protections to voting and housing and provided new protections against racially motivated violence. The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 complemented these civil rights milestones by attacking the economic inequalities that had long accompanied racial discrimination and exclusion.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which barred employment discrimination based on sex, race, color, religion, and national origins, energized the women’s movement to the founding of the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966. Activists also convinced Congress to protect such groups as older Americans, people with disabilities, and pregnant women so that they could participate fully in public and private life.

On April 4, 1968, civil rights leader and Nobel Peace Prize recipient Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated on his hotel room’s balcony. Legally charged looting and riots followed, putting even more pressure on the President Johnson administration to push through additional civil rights laws.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Martin Luther King, Jr. – Civil Rights Activist & Hero

The Battle of Athens: An Obscure American Revolution

Sources:

History.com

Jim Crow Laws

Library of Congress

Office of the Historian

U.S. Senate