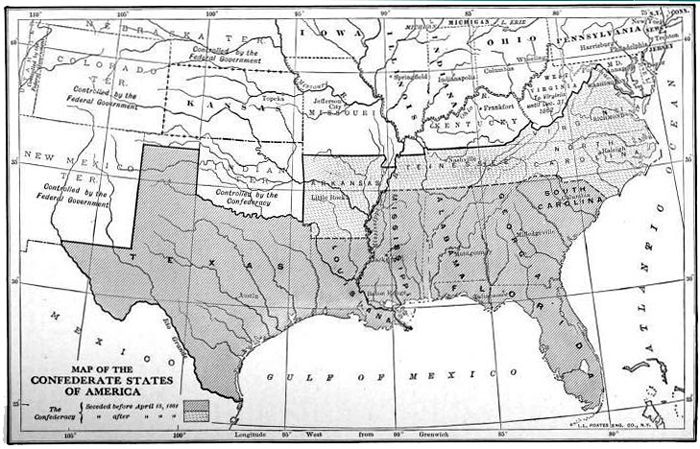

The Confederate States States of America also referred to as the Confederacy and the CSA, was an unrecognized power established in early 1861 by eleven southern slave states that seceded from the United States of America.

Torn apart primarily by the issue of slavery, these states also had issues with the Federal Government that included states’ rights, policies favoring Northern over Southern economic interests, expansionism, modernization, and taxes.

Though many disagreements between the North and South had been brewing since the American Revolution ended in 1782, the crisis began to come to a head in the 1850s as the nation grew westward.

As new territories such as Kansas and Nebraska were added, the Southern factions felt that slavery should be allowed in these new territories, while the “Free Soilers” were set against it. This led to open warfare between Kansas and Missouri, generally referred to in history as “Bleeding Kansas.” One of the many precursors to the Civil War, these battles pitted neighbor against neighbor.

This dispute over the expansion of slavery into new territories and the election of Abraham Lincoln as president on November 6, 1860, finally led to the secession of eleven Southern states. Though Lincoln did not propose federal laws making slavery unlawful where it already existed, his sentiments regarding a “divided nation” were well known.

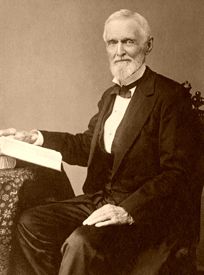

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina was the first state to secede from the Union, and within two months, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas followed. On February 4, 1861, the Confederate States of America was organized, and a few days later, on February 9, a provisional government was formed with President Jefferson Davis at its helm.

After the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861, and Lincoln’s subsequent call for troops on April 15, 1861, four more states declared their secession, including Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina.

Kentucky and Missouri border states declared neutrality early in the war, as their citizens were divided in their loyalties. Kentucky gradually came to side with the North, but Missouri remained divided for the duration of the Civil War.

The southern parts of New Mexico and Arizona allied with the Confederacy. When the Union abandoned federal forts and installations in Indian Territory (Oklahoma), the South claimed this territory.

Breaking away from Virginia during the Civil War, Union loyalists would form a new state called West Virginia, officially admitted to the Union in June 1863. Like other border states, its population had mixed loyalties.

Organization of the Confederacy

The Confederate States of America was organized at a congress of delegates from South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, which met at Montgomery, Alabama, on February 4, 1861. A provisional government was established within a few days, and on February 9th, Jefferson Davis was made president and Alexander H. Stephens vice-president. This temporary government was to continue for only one year, and its constitution was not submitted to the states or the people of the states for ratification. However, a “permanent” constitution was drawn during the weeks immediately following, approved by Congress on March 11th, and submitted to the conventions of the seceded states. It was promptly adopted, though it would not become effective until February 22, 1862.

In the meantime, the provisional government assumed, with unanimous consent, all the common and general functions which the states could not exercise. In so far as the South was concerned, all the initiatory steps of the Civil War were taken by this government. Texas joined the Confederacy in March; Virginia in April; North Carolina in May; Tennessee and Arkansas in June; while large portions of Kentucky and Missouri also cast in their lots with the South and sent delegates to the Confederate Congresses. Thus, the area embraced about 800,000 square miles, exclusive of what was held in the Indian Territory and New Mexico. The population of these states and parts of states was about 10,000.000, of which fully 4,000,000 were African-Americans.

With this organization accomplished, the Confederate authorities appointed commissioners to Europe and the Federal Government to recognize it as an independent power. The commissioners appeared in Washington, D.C., and demanded jurisdiction over the forts and other property of the older government within the bounds of the seceded states.

Meanwhile, the Confederate Government assumed the jurisdiction in question, hastened the organization of an army and a navy, and made appropriations and loans for these and other purposes, all in the most orderly manner and without any opposition on the part of the people of the southern states. However, there was grave dissatisfaction in the mountain districts where slavery and its influence had not penetrated. The Federal authorities refused to recognize the Confederate agents or to concede any rights concerning the forts or other property. But, the European powers acknowledged the new nation’s existence by granting it the standing of a belligerent in international law, an important concession, especially in commercial matters and applying the rules of war. It was generally expected that formal diplomatic recognition would soon follow. In the North, there was a strong party, supported by the great financial interests of New York, which advised that the southern states be allowed to “depart in peace.” Even President Abraham Lincoln thought seriously of such a solution to the problem, and William H. Seward, the Secretary of State, gave the southern commissioners, A.B. Roman, John Forsyth, and Martin Crawford, assurance that the forts and other property of the Federal Government would be surrendered without a struggle.

The War Begins

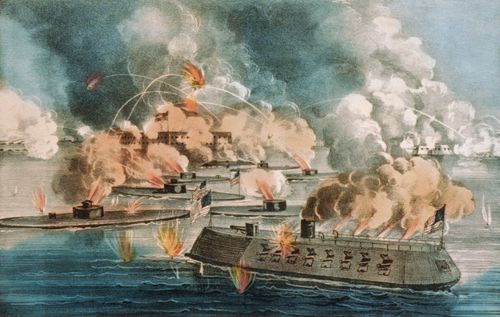

The great fight at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, April 7, 1863, by Courier & Ives.

However, the meaning of separation, the injury to northern commerce and manufactures, the probable difficulties about boundaries, and the equally probable future conflicts wrought a change in sentiment. President Abraham Lincoln, always a true interpreter of public opinion, finally decided not to negotiate with the southern representatives, especially not to surrender Fort Sumter. This decision was reached between April 9th and 12th, 1861.

At the same time, the southern leaders began to fear a restoration of the Union on some such basis as the proposed Crittenden Compromise; and the Confederate Government found it necessary to hold its own ardent supporters together to hasten a decision. The firing upon Fort Sumter on the night of April 12, 1861, aroused the latent military spirit of the North and South people, and war soon followed.

The immediate outcome of President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers on April 15 was the official loss to the Federal Government of the Border States. The accession of so much territory north of the lower southern states added greatly to the enthusiasm of the South. It caused the removal of the Confederate capital from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond, Virginia. In the early summer, the armies of the two sections of the United States prepared for actual conflict on the soil of northern Virginia.

Troubles in the Government

In the meantime, the new Confederate Government was showing early troubles as the first Cabinet was composed of men who had either opposed the secession movement or had been rivals of Jefferson Davis for years. Vice-President Alexander Stephens had never been on friendly terms with Davis and had been the most powerful opponent of secession in the South as late as January 1861. The first Secretary of State, Robert Toombs, was hostile to Davis. Within months of his appointment, he stepped down to join the Confederate States Army as a brigadier general in July 1861. Christopher Memminger, the first Secretary of the Treasury, had consistently fought the separatist movement since 1832; L. Pope Walker, the first Secretary of War, had been a leader of the unionist forces of North Alabama, and even Davis himself had advised South Carolina not to secede as late as November 10, 1860.

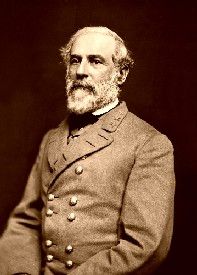

Of the great generals whom the president of the Confederacy called to the leadership of the armies, only Albert Sidney Johnston believed in the propriety and necessity of the movement. Robert E. Lee had never been a state rights man, and late in April 1861, he lamented the “revolution” that the lower South had precipitated. Joseph E. Johnston agreed, though his political antecedents were less strongly national than Lee’s. In the Senate and House, a large minority — sometimes a majority — of the leaders was made up of men who had never believed in the wisdom of secession, though most of them acknowledged the right of a state to withdraw from the Union.

Recognition of the Confederate States

Despite the persistent efforts of Confederate agents from 1861 to 1865 to secure recognition, it failed. The U.S. Federal Government refused al to hold any official communication that could be interpreted as recognition of the existence of the Confederacy as a separate power. In addition, the U.S. Federal Courts held that the Confederate States were “an unlawful assemblage without corporate power.”

In the meantime, the Confederacy pinned its hopes for survival on military intervention from Europe. The South based their expectations on Europe, especially England, could not endure the lack of cotton. These expectations would prove mistaken. When the U.S. Federal Government clarified that any diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy meant war with the United States, no nation was willing to go to war and would not assist or recognize the Confederacy.

Early Reverses

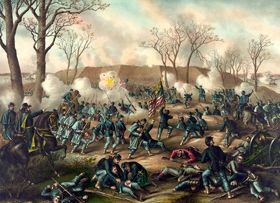

Battle of Fort Donelson, Tennessee

The frontier of the Confederacy extending from Norfolk, Virginia, through the southwestern counties of Virginia and Kentucky to western Missouri was broken at Forts Donelson and Henry, Tennessee, in February 1862, and again at Pittsburg Landing in western Tennessee in the following April. In May 1863, New Orleans fell into the hands of the Federals, and with the fall of Murfreesborough, Tennessee, and Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1863, the western part of the Confederacy was cut off from the main group of states.

From the autumn of 1862, the seafront from Chesapeake Bay to Galveston was guarded by an ever-tightening cordon of armed warships. This blockade effectually closed the ports of the South against all foreign trade. Only along the northern boundary of Virginia did the armies of the Confederacy make any inroads upon the North, which ceased after General Lee’s defeat at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in July 1863. This was followed by General William T. Sherman’s march to the sea, which, in the autumn of 1864, cut through the heart of the Confederacy.

Under these discouraging conditions, petty personal jealousies arose among the army officers, not unlike those between the civil authorities of the Confederate and state governments. Joseph E. Johnston, who was connected with many of the most powerful families of the South, became intensely hostile toward President Davis and was jealous of the growing fame of General Lee, who was the very personification of the “first family” influence. The Confederate Congress generally sided with Johnston against the President but feared openly antagonizing Lee.

Confederate Generals

In the beginning, the South had a great advantage in the character of the higher officers who resigned their commissions in the United States Army to accept commands in the army established by the Confederacy. The chief of these were Robert E. Lee, Joseph E. Johnston, Albert Sidney Johnston, and Pierre G. T. Beauregard, all leaders of great ability and long experience in actual warfare. The prestige these names carried and the confidence they inspired in the success of the cause had much to do with the rapid formation and successful organization of the armies with which the Confederacy began operations. During the first year of the struggle, the “new nation” put more than 400,000 men into the field and began building many warships in English and French docks. During the four years of the war, almost 900,000 soldiers were enlisted and equipped. Whether he had originally favored the movement, everyone in the South counted it a disgrace not to have a part in the fighting. For years, no one in the older southern states would admit that he or any of his family shirked a military duty or sent a substitute to the front.

Economic Conditions

Enthusiasm for the cause and early victories in the field led to the belief that success was only a matter of time. In this confident expectation, the Confederate Government contracted a debt of $1,500,000,000, and the states, counties, and municipalities must have spent almost as much. Ultimately, the Federal Government repudiated almost all of this debt during Reconstruction in 1865-66. A small portion of this huge debt was due to European creditors, not more than $10,000,000, but all the rest was a total loss to the people of the South, mainly to those who had been slave owners. The loss in cotton production and export decreased from four million to less than one million bales between 1860 and 1865 and would not again reach its former state of profitability until 1870. The corporate wealth of railroads and manufacturers was almost wholly lost during the war. At the beginning of the war, the South had three main lines of railroad, some of which were extended to deal with the wartime traffic. Cut off from the steel and iron mills of the North and England, the railroad soon ran down and, in the end, became almost worthless.

End of the Confederacy

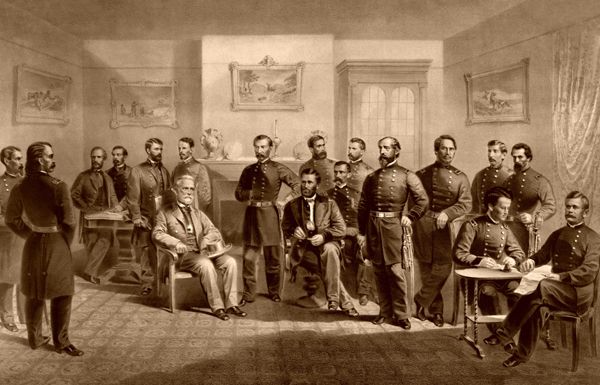

Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrenders to Union General Ulysses S. Grant, by Major and Knapp.

Throughout the war, troubles in the Confederate Government continued. From November 1864 to February 1865, a strong party in the Confederate Congress, led by Alexander H. Stephens and supported by Governors Zebulon B. Vance of North Carolina and Joseph E. Brown of Georgia, urged the impeachment of Jefferson Davis and the establishment of a military dictatorship with General Robert E. Lee at the head. Their refusal of Lee to support the plan prevented a practical attempt at its realization.

The Confederate States of America effectively collapsed after Ulysses S. Grant captured its capitol of Richmond, Virginia, and Robert E. Lee’s army in April 1865. The remaining Confederate forces surrendered by the end of June as the U.S. Army took control of the South.

After the war, a decade-long process known as Reconstruction began, which expelled ex-Confederate leaders from office, enacted civil rights legislation, and imposed conditions on the state’s readmission to Congress. The war and subsequent Reconstruction left the South economically weak, and it would be years before they would regain prosperity.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2023.

About This Article: Much of this article is part of the Cyclopedia of American Government, Volume 1, edited by Andrew C. McLaughlin and Albert Bushnell Hart, 1914. However, the article that appears here is far from the original text as it has been heavily edited, truncated, and additional information added.

Also See:

Bleeding Kansas & the Missouri Border War

Civil War (main page)