Adventures & Tragedies on the Overland Trail

John Butterfield & the Overland Mail Company

Canyon Station Treasure Near Kingman, Arizona

Cowboys, Trail Blazers, & Stagecoach Drivers List

Mary Fields – Lady Stagecoach Driver

Clark “Old Chieftain” Foss – Boisterous California Stage Driver

George “Baldy” Green – A Popular Stage Driver

Haunted Camp Floyd & the Stagecoach Inn

Ben Holladay – The Stagecoach King

A Journey to Denver via the Butterfield Overland Dispatch

Knights of the Lash: Old-Time Stage Drivers of the West Coast

A Midnight Adventure in Nevada

Henry “Hank” Monk – Famous Stage Driver

Overland Mail on the Santa Fe Trail

The Overland Stage and Telegraph Lines

Phantoms of Vallecito Stage Station

Portneuf Canyon, Idaho Stage Robbery

Delia Haskett Rawson – Carrying the U.S. Mail

Russell, Majors & Waddell – Transportation in the Old West

Stagecoach Kings (Lines) & Drivers

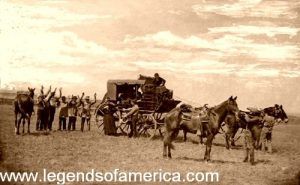

Stagecoach & Wagon Photo Gallery

Tales of the Overland Stage in Nevada

Tales of the Shotgun-Messenger Service

Riding in a Stage

Creeping through the valley, crawling o’er the hill, Splashing through the branches, rumbling o’er the mill, Putting nervous gentlemen in a towering rage. What is so provoking as riding in a stage?

Spinsters fair and forty, maids in youthful charms, Suddenly are cast into their neighbors’ arms; Children shoot like squirrels darting through a cage- Isn’t it delightful, riding in a stage?

Feet are interlacing, heads severely bumped, Friend and foe together get their noses thumped; Dresses act as carpets-listen to the sage; “Life is but a journey taken in a stage.”

— From: Six Horses by Captain William Banning & George Hugh Banning, 1928.

Numerous stagecoach lines and express services dotted the American West as entrepreneurs fought to compete for passengers, freight, and, most importantly, profitable government mail contracts.

Often braving terrible weather, pitted roads, treacherous terrain, and Indian and bandit attacks, the stagecoach lines valiantly carried on during westward expansion, despite the hazards.

Though stagecoach travel for passengers was uncomfortable, it was often the only means of travel and was safer than traveling alone. If passengers wanted to sleep, they were required to sit up, and it was considered bad etiquette to rest one’s head on another passenger. There were also numerous other rules required of passengers, including abstaining from liquor, not cursing or smoking if ladies were present, and others.

Though many types of stagecoaches were used for various purposes, the most often used for passenger service was the Concord Stagecoach, first built in 1827.

Designed by the Abbot Downing Company, the coach utilized leather strap braces underneath, giving them a swinging motion instead of a spring suspension, which jostled passengers up and down. Over the years, the New Hampshire-based company manufactured over 40 types of carriages and wagons, earning a reputation that their coaches rarely broke down; instead, they just “wore out.” The coaches weighed more than a ton and cost between $1500 and $1800. The stages had three seats, providing nine passengers with little legroom. Passengers were also allowed to ride on top. The term “stage” originally referred to the distance between stations as each coach traveled the route in “stages.”

The stage lines’ most profitable contracts were U.S. Mail contracts, which were hotly contested. Though the Pony Express is often credited with being the first fast mail service from the Missouri River to the Pacific Coast, the Overland Mail Company began a twice-weekly mail service in September 1858. Each service crossed more than 2,800 miles from San Francisco, California, to Missouri and was required to be completed in 25 days or less.

Along the many stage routes, stations were established about every 12 miles that included two types of stations — “swing” and “home.” As the stage driver neared the station, they would blow a small brass bugle or trumpet to alert the station staff of the impending arrival.

The larger stations, called “Home Stations,” generally run by a couple or family, were usually situated about 50 miles apart and provided passengers with meager meals and overnight lodging. However, “lodging” was often no more than a dirt floor.

These stations also included stables where the horses could be changed, a blacksmith and repair shop, and a telegraph station. Here, drivers were usually switched.

The more numerous “swing” stations, generally run by a few bachelor stock tenders, were smaller and usually consisted of little more than a small cabin and a barn or corral. Here, the coach would stop for about ten minutes to change the team and allow passengers to stretch before the coach was on its way again.

At one time, more than 150 stations were situated between Kansas and California.

Though there were numerous lines throughout the Old West, some figure into history more prominently than others, most notably John Butterfield’s Overland Mail Company, Wells Fargo & Co., and the Holladay Overland Mail and Express Company.

As the railroad continued to push westward, stagecoach service became less and less in demand. With the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, transcontinental stage-coaching ended.

However, this was not the end of the stagecoach, as it continued to be utilized in areas without railroad service for several more decades. In the end, the introduction of the automobile led to the end of the stagecoach in the early 1900s.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2023.