Baltimore, Maryland, is the most populous city in the state, with 585,708 people at the 2020 census. It is the 30th-most populous city in the United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the Baltimore metropolitan area was estimated to be 2,838,327, making it the 20th-largest metropolitan area in the country.

Baltimore is in north-central Maryland on the Patapsco River, close to where it empties into the Chesapeake Bay. It has a total area of 92.1 square miles, of which 80.9 square miles is land and 11.1 square miles is water. Baltimore County almost surrounds Baltimore, but it is politically independent of it. Anne Arundel County borders it to the South.

Paleo-Indians used this area as a hunting ground since at least the 10th millennium B.C. During the Late Woodland period, the archaeological culture known as the Potomac Creek complex resided from Baltimore south to the Rappahannock River in present-day Virginia. In the early 1600s, the Susquehannock tribe began to hunt there.

Iroquoian-speaking people controlled all of the upper tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay but refrained from much contact with Powhatan in the Potomac region and south into Virginia. Pressured by the Susquehannock, the Algonquian-speaking Piscataway tribe stayed well south of the Baltimore area, primarily inhabiting the Potomac River’s north bank.

European colonization of Maryland began with the arrival of the merchant ship The Ark carrying 140 colonists at St. Clement’s Island in the Potomac River on March 25, 1634. Europeans then settled the area further north, in Baltimore County. The original county seat, known today as Old Baltimore, was located on Bush River within the present-day Aberdeen Proving Ground. The colonists engaged in sporadic warfare with the Susquehannock, whose numbers dwindled primarily from new infectious diseases, such as smallpox, endemic among the Europeans.

Baltimore was designated an independent city by the Constitution of Maryland in 1651. It was named after Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore, an Anglo-Irish Irish House of Lords member and founding proprietor of the Province of Maryland. The Calverts took the title Barons Baltimore from Baltimore Manor, an English Plantation estate they were granted in Ireland.

When Baltimore County was laid out in 1659, embracing a much larger area than the present county, the uninhabited land was partly meadow and partly marsh at the foot of irregular wooded bluffs divided by a creek later called Jones Falls. Below the bluff, the Falls meandered sharply westward, then eastward before turning south to the broad cove later named the North West Branch of the Patapsco River. Patapsco Falls came in from the west, emptying into the cove later named the Middle Branch. Between the two bodies of water lay a low peninsula called Whetstone Neck.

In June 1661, land on the west side of Jones Falls near the water was surveyed for David Jones, who soon settled here. In the following decades, numerous tracts were patented, producing many settlements such as Haphazard, Hale’s Folly, Luns Lot, Ridgeley’s Delight, Fell’s Prospect, Gallow Bar, David’s Fancy, and The Choice.

In 1696, Charles and Daniel Carroll resurveyed and patented 1,000 acres on the west side of Jones Falls, including part of an earlier patent called Cole’s Harbor.

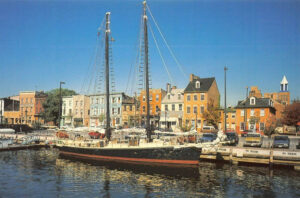

The Colonial General Assembly of Maryland created the Port of Baltimore at Locust Point in 1706 to support the tobacco trade with Europe. Fells Point, the deepest point in the natural harbor, soon became the colony’s main shipbuilding center, later becoming a leader in constructing clipper ships.

By 1726, there was a gristmill on the east bank of the Falls, and near it were three dwellings, a store, and some tobacco houses.

Tobacco growers desired a customhouse to ship their tobacco to a port. Local landholders, therefore, united, with Daniel and Charles Carroll in the lead, to try to establish a town on the north side of the Patapsco River, but its owner refused to sell. However, another site was selected for the new town, which Governor Benedict Leonard Calvert approved on August 8, 1729.

Surveyors began laying out the town on January 12, 1730. It was laid out roughly in the shape of an arrowhead with the tip near the present intersection of Hopkins Place and Redwood Street. This original townsite of 60 acres, for which the Carrolls were paid the equivalent of about £600. Soon after the first lots were taken up, a causeway across Harrison’s Marsh and a bridge across Jones Falls were constructed to link the new town with Jones Town, the older settlement east of the Falls.

After Baltimore’s founding, mills were built behind the wharves. The California Gold Rush led to many orders for fast vessels; many overland pioneers also relied upon canned goods from Baltimore.

Baltimore grew swiftly in the 18th century. Its plantations produced grain and tobacco for sugar-producing colonies in the Caribbean.

By 1752, the town had just 27 homes, including a church and two taverns, with a population of about 200. Jonestown and Fells Point had been settled to the east. The three settlements, covering 60 acres, became a commercial hub.

In 1755, a boatload of French Acadian exiles from Nova Scotia arrived and were received with great hospitality, even though England had expelled them from their homeland because of their unwillingness to give up their French allegiance. In time, the Acadians would construct small houses along South Charles Street; this section of Baltimore was called French Town for a century.

The port grew slowly but steadily. In 1756, a Baltimore bottom cleared for the British West Indies with a diversity of cargo consisting of Indian corn, flour– ground in mills along the Patapsco and Jones Falls — beans, hams, bread, iron, staves, and heading, peas, and of course tobacco. The vessel returned with the usual sugar, rum, and slaves. This event marked the end of Baltimore Town’s dependence on tobacco and the beginning of an era of diversified shipping. Two years later a cargo of wheat from upland farms was shipped to New York.

In a few years, Baltimore had a pottery and a distillery. An educator from London taught young men writing, arithmetic, merchants’ accounts, geometry, etc., taught young ladies the ‘Italian hand,’ and sold choice West India rum by the hogshead, loaf-sugar, coffee, chocolate, Madeira wine, and cedar desks.

In July 1762, a visitor, Benjamin Mifflin, noted in his diary that the town had about 150 houses, mostly of brick, and 30 or 40 under construction. At that time, there were two bridges over the creek.

Baltimore established its public market system in 1763.

In 1765, Nicholas Hasselbach and William Goddard introduced the first printing press and newspapers to Baltimore.

Baltimore played a part in the American Revolution. City leaders such as Jonathan Plowman Jr. led many residents to resist British taxes, and merchants signed agreements refusing to trade with Britain.

Baltimore had been made the county seat in 1768, and a courthouse was built near the site of the Battle Monument on a bluff that was then some 30 or 40 feet above the present street level. By this time, the town had three or 4,000 inhabitants, but catching crabs with a stick was still possible.

When, in 1770, two sloops with contraband arrived, they were forced to leave the port, and Baltimoreans passed a resolution not to trade with Rhode Island when the New England colony violated the intercolonial nonimportation agreement.

The Maryland Journal and The Baltimore Advertiser were first published by William Goddard in 1773.

In 1774, Baltimore established the first post office system in the United States. That year, a Committee of Correspondence was appointed, and resolutions were passed recommending that all trade with Great Britain and the West Indies cease — even though the trade with the West Indies was then the most profitable carried on by Baltimore citizens. Only four days after the Virginia House of Burgesses made a similar recommendation and before the news had been brought up the Bay, Baltimore citizens in a general meeting went on record as favoring a convention of representatives from all the colonies. A militia company was formed in December, and Mordecai Gist was elected captain. Six months later, after the news of Lexington and Concord had reached the town, seven companies were drilling in Baltimore.

Baltimore, however, had made her most significant contribution on the sea. In October 1775, the Continental Congress passed an act to form a navy. In the same month, the Continental Marine Committee at Baltimore had fitted out two of the first cruisers of the American Navy. A new flag had been sent down from Philadelphia to be used on one of these vessels, the Hornet, and Joshua Barney, the recruiting officer of the ship, had unfurled this flag to the music of fifes and drums. ‘The heart-stirring sounds of the Martial instruments, then a novel incident in Baltimore,’ wrote Barney’s wife, ‘and the still more novel sight of the Rebel colors gracefully waving in the breeze attracted crowds of all ranks and eyes to the gay scene of the rendezvous, and before the setting of the same day’s sun, the young recruiting-officer had enlisted a full crew of jolly “rebels” or the Hornet.

A Maryland navy also did good service in keeping down plunderers in the bay and, at times, suppressing Tory uprisings. Many of these vessels were built and equipped in Baltimore. They ranged in size from tiny barges carrying six or a dozen ‘jolly rebels’ with perhaps as many muskets to cruisers of twenty-two guns. The larger vessels might have such mild names as Defense^ Friendship or Amelia, but the barges carried such mighty names as Revenge, Terrible, Intrepid, or Feamaught.

In 1776, the town had some 6,700 inhabitants.

During the American Revolution, the Second Continental Congress, fleeing Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, before the city fell to British troops, moved their deliberations to Henry Fite House on West Baltimore Street from December 20, 1776, to February 27, 1777. This permitted Baltimore to serve briefly as the nation’s capital before it returned to Independence Hall in Philadelphia on March 5, 1777.

Between April 1, 1777, and March 14, 1783, 248 vessels, most of them owned by Baltimoreans, sailed from the Patapsco to capture what they could from the British, and they succeeded so well that British merchants for more than 30 years referred to Baltimore as a *nest of pirates.’ When a prize was captured, it might be manned by a skeleton crew and sent to the nearest American port, or if this was impossible, it was burned or sunk. The damage to English shipping during this period has been estimated at £1,000,000.

Baltimore Town had contributed perhaps more than its share of the money needed to carry on the war and, like all other American towns of the period, had suffered from business disruption. However, Baltimoreans had learned to build fast ships and were to profit greatly from this knowledge during the succeeding period of privateering and slave running.

Lexington Market, founded in 1782, is one of the oldest continuously operating public markets in the United States today. It was also a center of slave trading. Black people were also sold at numerous sites throughout the downtown area, with sales advertised in The Baltimore Sun. Both tobacco and sugar cane were labor-intensive crops.

Baltimore was excited by the approach of British soldiers in 1780, prompting General Greene to report that Baltimore was in ‘so defenseless a state that a twenty-gun ship might lay the town under contribution.’

In July 1783, the veterans returned from the war, ‘penniless and in rags,’ under the command of Mordecai Gist, then a brigadier general.

The Baltimore Water Company, the first water company chartered in the newly independent nation, was established in 1792.

Baltimore, Jonestown, and Fells Point were incorporated as the City of Baltimore in 1796-1797.

In 1797, the newly elected mayor approved an ordinance to prepare a lottery scheme to raise a sum of money for the use of the city of Baltimore. For many years, Baltimore enjoyed lotteries. They were held to raise money for churches, schools, colleges, and civic improvements, including the Washington Monument. One winter, a lottery was held for its own sake, and the money would be used for any suitable enterprise in the spring.

In 1808, after the passage of the Embargo Act, in a huge ceremony attended by all citizens, 1,200 of them on horseback, the city burned 720 gallons of gin because the master of a vessel had paid duty on it in an English port.

The Federal census of 1810 showed a population of 45,000.

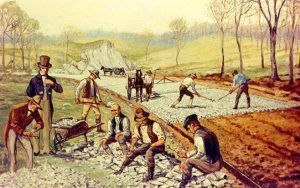

Cutting an approximately 820-mile-long path through Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, the National Road was built between 1811 and 1834 and was the first federally funded road in U.S. history. Presidents George Washington and Thomas Jefferson believed a trans-Appalachian road was necessary to unify the young country. On March 29, 1806, Congress authorized the construction of the road, and President Thomas Jefferson signed the act establishing what was first called the Cumberland Road that would connect Cumberland, Maryland, to the Ohio River. Soon, Conestoga wagons brought wheat, corn, and pork, leaving with manufactured wares for the Ohio Valley. The road promoted westward expansion, encouraged commerce between the Atlantic colonies and the West, and paved the way for an interstate highway system. The National Road later became part of U.S. Route 40.

After the declaration of the War of 1812, patriotism ran so high that the office of a Federalist newspaper, which opposed the war, was raided. During the ensuing riot, there was loss of life on both sides. The editor and his friends were tortured. One of the latter. General James M. Lingan, died. Another, General Tight-Horse Harry ‘ Lee, father of Robert E. Lee, remained crippled for life.

Besides contributing to the Federal Navy, Baltimore enthusiastically resumed its old privateering business. Four months after the declaration of war, 42 privateers, carrying 330 guns and about 3,000 men, had left Baltimore, and some of them preyed on English shipping within a few miles of the British coast.

A British statesman called Baltimore the great depository of the hostile spirit of the United States against England.’ A British admiral said, ‘Baltimore is a doomed town,’ a London paper declared that ‘the truculent inhabitants of Baltimore must be tamed.’

Citizens were worried. Fort McHenry had been neglected, and big guns were scarce. The Federal Government had sent many of Baltimore’s fighting men on the disastrous Canadian expedition and could not aid the city. Baltimore would have to fight its own battle. Fort McHenry was repaired as soon as possible, and the guns of an abandoned French frigate were borrowed from the consul. Furnaces were built to make the 42-pound balls. Forty pieces of artillery were stationed on elevated ground east of the city, and every man and boy was assigned to the military duty. A Baltimore seamstress made a big flag for Fort McHenry.

Then, the news came that Washington, D.C., had been captured and partly burned on August 24, 1813. The British army landed on North Point under the command of General Ross, and the British fleet came up the Patapsco River.

The Battle of Baltimore on September 12-15, 1814, was a pivotal engagement during the war, culminating in the failed British bombardment of Fort McHenry. Fort McHenry guarded Baltimore, and the city would also go if the fort fell. All day, the English ships fired shots and shells at the fort. During the night, the attack continued. During this engagement, Francis Scott Key, a prisoner of a British man-of-war, wrote a poem that would become The Star-Spangled Banner, which was eventually designated as the American national anthem in 1931.

The Treaty of Ghent in 1814 ended privateering, and the Baltimore vessels became once more the carriers of vigorous foreign trade. The principal export was flour. With abundant water power and easy access to large wheat-growing areas, Baltimore became one of the largest milling centers in the country.

Baltimore pioneered gas lighting in 1816, and its population increased in the following decades with the simultaneous development of culture and infrastructure.

By 1820, Baltimore’s population had reached 60,000, and its economy had shifted from its base in tobacco plantations to sawmilling, shipbuilding, and textile production.

By 1825, Baltimore’s population had grown to about 72,000; there were some 60 mills within a few miles of the city.

The soft flour produced was found exceptionally well suited to tropical conditions; this advantage, combined with its advantageous position, made Baltimore the largest exporter of flour to Antillean and South American ports. Returning vessels brought coffee from Brazil and guano from Peru.

Baltimore acquired its moniker “The Monumental City” after President John Quincy Adams visited the city in 1827. This was due to the distinctive local culture and a unique skyline with churches and monuments.

Baltimore, in the 1820s and 1830s, was a center for the domestic slave trade. Slaves were brought across the Atlantic in the fast Baltimore clippers and transshipped to Southern ports. Significant numbers of escaped slaves captured in Pennsylvania and New York were returned to their owners by way of Baltimore.

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the nation’s oldest railroad, was built in 1830 and cemented Baltimore’s status as a major transportation hub. It gave producers in the Midwest and Appalachia access to the city’s port. Baltimore’s Inner Harbor was once the second leading port of entry for immigrants to the United States. In addition, Baltimore was a significant manufacturing center. After a decline in major manufacturing and heavy industry and restructuring of the rail industry, Baltimore shifted to a service-oriented economy.

Baltimore had one of the worst riots of the antebellum South in 1835 when bad investments led to the Baltimore Bank Riot, which led to the city being nicknamed “Mobtown.” The streets of Baltimore had seen violence at long intervals since the Revolutionary days, but about the middle of the century, violence and fraud became a part of various groups’ regular political techniques and, finally, the sole means of winning an election. Famous author and poet Edgar Allan Poe was accidentally and tragically involved in one of Baltimore’s roughhouse elections.

The city created the world’s first dental college, the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery, in 1840.

Baltimore shared the world’s first telegraph line between Baltimore and Washington, D.C., in 1844.

The city remained a part of surrounding Baltimore County and continued to serve as its county seat from 1768 to 1851, after which it became an independent city.

During the presidential election of 1856, there was a street battle between Know-Nothings and the Democrats, with each side using a brass cannon. Reform was finally accomplished by the more responsible citizens of the town, aided by voters of the State; an assembly was elected, which in 1860 made the needed changes in the election laws and put the police under direct State control.

The outbreak of the Civil War found Baltimore citizens divided in their sympathies, and the people of the State had the opportunity to vote on the question of secession. Maryland, a slave state with limited popular support for secession, remained part of the Union during the Civil War following the 55-12 vote by the Maryland General Assembly against secession.

On April 19, 1861, four soldiers and eleven citizens were killed in a riot that occurred as the Sixth Massachusetts Regiment was marching across town from one railroad station to another. News of this event moved the Baltimore resident James Ryder Randall, then in New Orleans, Louisiana, to write the stirring song, Maryland, My Maryland.

This and other events brought military rule to the State, and throughout the war, the city was subject to strict supervision. Some of its officials were deprived of office, and their constitutional rights were suspended. A ring of forts encircled the city, with guns trained not outward but toward its heart.

In July 1864, after the defeat of General Lew Wallace on the Monocacy River, a Confederate force under General Bradley T. Johnson, composed mainly of Baltimore residents and other Marylanders, passed close to the city. Bridges were burned, and trains were captured. Northern sympathizers in Baltimore were in terror while Southern sympathizers prepared to greet an “army of deliverance.” However, Baltimore was not the movement’s objective, and the Confederates moved on toward Washington, D.C.

The war disrupted the city’s everyday commerce and deprived it of its extensive market in the South. However, as the nearest large city to the scene of operations, it became an important military depot and profited from the traffic in army supplies. When demobilization at the end of the war put an end to this business, Baltimore was faced with a problem of reconstruction almost as significant as that of any city of the Confederacy; among newcomers of this period were many members of leading Southern families seeking to recoup their fortunes.

After several years of stagnation, the city began to recover. New industries were established, new markets were found in Europe and elsewhere, and significant improvements were made in port and railroad facilities.

Baltimore’s population was surpassed by St. Louis, Missouri, and Chicago, Illinois , in 1870.

Amid the long depression that followed the Panic of 1873, an attempt to lower workers’ wages led to strikes and riots. Strikers clashed with the National Guard, leaving ten dead and 25 wounded.

Throughout the remainder of the 19th century, Baltimore continued to grow as a trade center, and the manufacture of clothing, chemical fertilizer, and iron and steel products gained importance. Flour milling declined because of competition from the Middle West. Oyster packing was always prominent in the city’s economy, and in 1880, Baltimore was the world’s chief packing center. Afterward, however, the industry steadily declined due to the depletion of oyster beds in Chesapeake Bay.

At the end of the 19th century, European ship lines had erected terminals for immigrants, and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad made the port a major transshipment point.

Around the turn of the 20th century, Baltimore was the leading U.S. rye whiskey and straw hat manufacturer. It soon began refining crude oil brought to the city by pipeline from Pennsylvania.

On February 7-8, 1904, a fire in a warehouse near the corner of Liberty and Redwood Streets began, and it was soon out of control. Embers were blown from block to block by a robust southwest wind until the buildings of the civic center were endangered. Fire companies came from as far as New York City, New York, and Richmond, Virginia, and though buildings were dynamited, the flames were not checked until the wind shifted and drove them to the waterfront. The fire destroyed over 1,500 buildings in 30 hours, leaving more than 70 blocks of the downtown area burned to the ground. Damages were estimated at $125 million in 1904 dollars.

While the ruins were still smoldering, the city began to plan a bigger and better Baltimore. The narrow downtown streets were widened and paved, and new and better buildings replaced the burned ones. Most of these new buildings were three or four stories high, though a few tall ones ranged from ten to 16 stories. Fortunately, three of Baltimore’s oldest and most imposing buildings escaped the fire — the post office, city hall, and the courthouse. As the city rebuilt, lessons learned from the fire improved firefighting equipment standards.

Before 1904, the city owned little important wharf property, but the fire made it possible to buy all the burned districts fronting the harbor. The city purchased this and laid out an excellent system of public wharves and docks open to the world’s commerce.

Baltimore lawyer Milton Dashiell advocated an ordinance to bar African Americans from moving into the Eutaw Place neighborhood in northwest Baltimore. He proposed to recognize majority-white residential blocks and majority-black residential blocks and to prevent people from moving into housing on such blocks where they would be a minority. The Baltimore Council passed the ordinance, which became law on December 20, 1910. The Baltimore segregation ordinance was the first of its kind in the United States. Many other southern cities followed with their segregation ordinances, but the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against them in Buchanan v. Warley in 1917.

By 1913, Baltimore averaged 40,000 immigrants yearly, but World War I closed off the flow.

The city grew in area by annexing new suburbs from the surrounding counties until 1918 when it acquired portions of Baltimore County and Anne Arundel County.

By the 1920s, Baltimore was the eighth-largest city in the United States. Because of her importance as a Southern railroad center and her excellent harbor on the largest bay of the Atlantic coast, Baltimore was called “The Gateway to the South.” Great ships from around the world unloaded their cargoes at her docks and took in return products from nearly every section of the United States. The railroads brought vast quantities of iron, coal, and grain to Baltimore, and ships and trains arrived with raw sugar, tobacco, fruits, and vegetables. Here, the oysters, fish, and crabs from the Chesapeake Bay and the products of the rich farmlands of Maryland and Virginia found a ready market. At that time, Baltimore led the world in the canning of vegetables and fruits, is one of the country’s largest banana markets, and more corn was exported from this city than from anywhere else in America.

After World War II, Baltimore’s population approached one million until it began to fall after the 1950 census. Baltimore reached its peak population of 949,708 that year.

A state constitutional amendment, approved in 1948, required a special vote of the citizens in any proposed annexation area, effectively preventing any future expansion of the city’s boundaries. Streetcars enabled the development of distant neighborhood areas such as Edmonson Village, whose residents could easily commute to work downtown.

Driven by migration from the Deep South and white suburbanization, the relative size of the city’s black population grew from 23.8% in 1950 to 46.4% in 1970. Encouraged by real estate blockbusting techniques, recently settled white areas rapidly became all-black neighborhoods, a process that was nearly total by 1970.

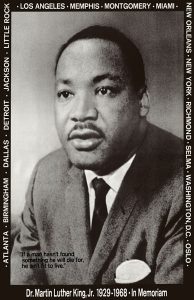

The Baltimore Riot of 1968, coinciding with uprisings in other cities, followed the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4, 1968. A total of 12,000 Maryland National Guard and federal troops were ordered into the city, but public order was not restored until April 12, 1968. The Baltimore uprising cost the city an estimated $10 million.

The city experienced challenges again in 1974 when teachers, municipal workers, and police officers conducted strikes.

By the beginning of the 1970s, Baltimore’s downtown area, known as the Inner Harbor, had been neglected and was occupied by a collection of abandoned warehouses. The nickname “Charm City” came from a 1975 meeting of advertisers seeking to improve the city’s reputation. Efforts to redevelop the area started with the construction of the Maryland Science Center, which opened in 1976, the Baltimore World Trade Center in 1977, and the Baltimore Convention Center in 1979. Harborplace, an urban retail and restaurant complex, opened on the waterfront in 1980, followed by the National Aquarium, Maryland’s largest tourist destination, and the Baltimore Museum of Industry in 1981.

Baltimore was among the top ten cities in population in the United States in every census up through the 1980 census.

In 1992, the Baltimore Orioles baseball team moved from Memorial Stadium to Oriole Park at Camden Yards, located downtown near the harbor.

The city opened the American Visionary Art Museum on Federal Hill in 1995.

The worst years for crime in Baltimore were from 1993 to 1996, with 96,243 crimes reported in 1995.

Baltimore saw the reopening of the Hippodrome Theatre in 2004, the opening of the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture in 2005, and the establishment of the National Slavic Museum in 2012. On April 12, 2012, Johns Hopkins held a dedication ceremony to mark the completion of one of the United States’ largest medical complexes – the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore – which featured the Sheikh Zayed Cardiovascular and Critical Care Tower and the Charlotte R. Bloomberg Children’s Center.

Unfortunately, Baltimore had a high homicide rate for several decades, peaking in 1993 and again in 2015. Baltimore’s 344 homicides in 2015 represented the highest homicide rate in the city’s recorded history — 52.5 per 100,000 people, surpassing the record ratio set in 1993 — and the second-highest for U.S. cities behind St. Louis, Missouri, and ahead of Detroit, Michigan. Of Baltimore’s 344 homicides in 2015, 321 (93.3%) of the victims were African-American. Following the death of Freddie Gray in April 2015, the city experienced major protests and international media attention, as well as a clash between local youth and police that resulted in a state of emergency declaration and a curfew.

On September 19, 2016, the Baltimore City Council approved a $660 million bond deal for the $5.5 billion Port Covington redevelopment project championed by Under Armour founder Kevin Plank and his real estate company Sagamore Development. Port Covington surpassed the Harbor Point development as the largest tax-increment financing deal in Baltimore’s history and among the country’s most significant urban redevelopment projects. The waterfront development that included the new headquarters for Under Armour, as well as shops, housing, offices, and manufacturing spaces, was projected to create 26,500 permanent jobs with a $4.3 billion annual economic impact. Goldman Sachs invested $233 million into the redevelopment project.

Once a predominantly industrial town with an economic base focused on steel processing, shipping, auto manufacturing, and transportation, the city experienced deindustrialization, which cost residents tens of thousands of low-skill, high-wage jobs. The city now relies on a low-wage service economy, which accounts for 31% of its jobs. In March 2018, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics calculated Baltimore’s unemployment rate at 5.8%, while one-quarter of Baltimore residents lived in poverty.

Continued population loss in prior decades led to its 2020 population of 585,708.

Unfortunately, Baltimore is also considered to be one of the most dangerous cities in the U.S. Experts say an emerging gang presence and heavy recruitment of adolescent boys into these gangs, who are statistically more likely to get serious charges reduced or dropped, are significant reasons for the sustained crime crises in the city. Overall reported crime dropped by 60% from the mid-1990s to the mid-2010s, but homicides and gun violence remain high and far exceed the national average.

Drug use and deaths by drug use are related problems that have impaired Baltimore for decades. Among cities greater than 400,000, Baltimore ranked second in its opiate drug death rate in the United States. The Drug Enforcement Administration reported that 10% of Baltimore’s population – about 64,000 people – are addicted to heroin, most of which is trafficked into the city from New York.

Today, the city’s top two employers are Johns Hopkins Hospital and Johns Hopkins University. Baltimore and its surrounding region are home to the headquarters of several other major organizations and government agencies, including the NAACP, ABET, the National Federation of the Blind, Catholic Relief Services, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, World Relief, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and the Social Security Administration.

Baltimore’s Port is the center of international commerce for the region and its World Trade Center. It houses the Maryland Port Administration and U.S. headquarters for major shipping lines. Baltimore is ranked 9th for total dollar value of cargo and 13th for cargo tonnage for all U.S. ports. It serves over 50 ocean carriers, making nearly 1,800 annual visits. Among all U.S. ports, Baltimore is first in handling automobiles, light trucks, farm and construction machinery, and imported forest products, aluminum, and sugar. The port is second in coal exports. The Port of Baltimore’s cruise industry, which offers year-round trips on several lines, supports over 500 jobs and brings over $90 million to Maryland’s economy annually. In the early morning hours of March 26, 2024, a cargo ship leaving the Baltimore Harbor struck a support column on the Francis Scott Key Bridge, causing a catastrophic collapse of the 1.6-mile bridge.

Baltimore is sometimes dubbed a “city of neighborhoods” since it comprises 72 designated historic districts traditionally occupied by distinct ethnic groups. Many of Baltimore’s neighborhoods have rich histories. Most notable today are three downtown areas along the port: the Inner Harbor, frequented by tourists because of its hotels, shops, and museums. It has some of the nation’s earliest National Register Historic Districts, including Fell’s Point, Federal Hill, and Mount Vernon. It also has more public statues and monuments per capita than any other city in the country. Nearly one-third of the city’s buildings are designated as historic in the National Register, which is more than any other U.S. city. The city has 66 National Register Historic Districts and 33 local historic districts.

The City of Baltimore is also home to the Baltimore Orioles of Major League Baseball and the Baltimore Ravens of the National Football League.

More Information:

Baltimore, Maryland

400 East Pratt Street, 10th Floor

Baltimore, Maryland 21202

1-877-Baltimore

Also See:

Great Cities Across the Nation

Sources:

Van Duyn Southworth, Gertrude, and Kramer, Stephen Elliott; Great Cities of the United States, Iroquois Publishing Company, 1922.

Visit Baltimore

Wikipedia

Writer’s Program of the Work Projects Administration; Maryland: A Guide To The Old Line State, Oxford University Press, 1940.