John Brown Mural

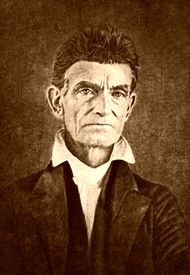

Frequently referred to as “Osawatomie Brown,” the famed abolitionist was born in Torrington, Connecticut, on May 9, 1800, a son of Owen and Ruth Mills Brown. His earliest American ancestor was Peter Brown, who came over on the Mayflower in 1620, and his grandfather, John Brown, was a captain in the Connecticut Militia during the American Revolution. His maternal grandfather, Gideon Mills, was also a soldier in the American Revolution.

In 1805 Owen Brown moved with his family to Ohio, where John grew to manhood, working on the farm and as a currier in his father’s tannery, part of the time as foreman. When he was about 20, he took up the study of surveying and followed that occupation for a few years. He then went to Crawford County, Pennsylvania, where he lived until 1835, before moving to Portage County, Ohio.

In 1846 he went to Springfield, Massachusetts, and bought and sold wool on commission. No sooner had he established himself in this business than he tried to force up the price of wool, but the New England manufacturers combined against him, and he was compelled to ship some 200,000 pounds to Europe, where he sold it at a loss, bankrupting him.

Gerrit Smith then gave him a piece of land near North Elba, New York, in the bleak, desolate region of the Adirondacks, and here Brown lived until 1851. He returned to Ohio and again engaged in the wool business, this time with better success.

John’s father, Owen was one of the early abolitionists, a disciple of Hopkins and Edwards, and from his earliest childhood, John breathed an atmosphere antagonistic to the institution of slavery. He was twice married — first to Dianthe Lusk, a widow who bore him seven children, and second to Mary Ann Day, by whom he had 13 children. Eight of his 20 children died young, and all those who grew to maturity were abolitionists. Five of his sons moved from Ohio to Kansas in 1854 and selected claims some 8 to 10 miles from Osawatomie, where their father joined them on October 5, 1855.

Father and sons were mustered in as militia by the Free-State party and turned out to aid in defense of Lawrence. Two of Brown’s sons were captured by the United States Cavalry, which was used to aid in enforcing the territorial laws passed by a pro-slavery legislature, and John Brown, Jr., with his hands fastened behind his back, was driven by a cavalry company nine miles on a trot to Osawatomie. Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography says: “This state of things must be fully remembered in connection with the so-called ‘Pottawatomie Massacre,’ which furnishes, in the opinion of both friends and foes, the most questionable incident in Brown’s career.”

In January 1859, Brown left Kansas with several slaves taken from Missouri owners and went to Canada, where he arranged the details for his raid on Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia. Through the National Kansas Committee, he secured 200 rifles, and on June 3, 1859, he left Boston with $500 in gold and permission to keep the rifles. Late that month, Brown and his associates rented a small farm near Harper’s Ferry, where they were to complete the preparations for their raid. Brown’s daughter, Anne, and a daughter-in-law were installed as housekeepers. Here, Brown was visited in August by Frederick Douglass, to whom he imparted his plan to seize the United States arsenal at Harper’s Ferry and, if necessary, to carry out his purpose, to capture the town itself.

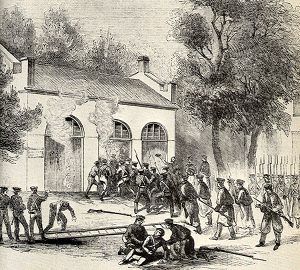

Douglass did not look favorably on the scheme, but Brown, having consecrated his life to the abolition of slavery, was not to be dissuaded. Accordingly, on Sunday evening, October 16, 1859, Brown mustered 18 men and moved on to the arsenal. At half-past ten, the gates were broken in with a crowbar, the diminutive guard was easily overpowered, and the raiders patrolled the town by midnight. Six men were sent to bring in some planters living in the vicinity with their slaves, it being Brown’s idea to free and arm the negroes to aid in bringing about a general uprising. Unhappily for the scheme, a train got through Harper’s Ferry and carried the news to Washington.

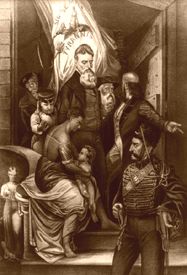

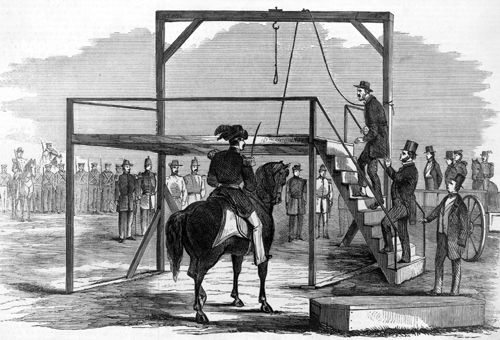

Captain Robert E. Lee, who afterward won distinction as a Confederate general, hurried from Washington with a company of Marines. The citizens armed themselves to aid the troops in capturing the raiders. Brown and six of his men barricaded themselves in the engine room and held out against great odds until two of his sons were killed, and he was wounded. He was tried before a Virginia court, convicted of treason, and sentenced to be hanged. His execution took place on December 2, 1859, and it is said that no man ever met his fate with greater fortitude. His body was buried at North Elba, Essex County, New York, near the farm given to him by Gerrit Smith.

John Brown has been called a fanatic, and some have even gone so far as to adjudge him insane, though there is no positive evidence to show that he was mentally unbalanced. From boyhood, the doctrines of abolition had been drilled into him until the idea that all men ought to be free became an obsession with him.

His methods were not always of the best character, but he had the courage of his convictions and was willing to lay down his life for a principle. His Black Jack and Osawatomie battles were insignificant compared to Gettysburg or Chickamauga. Still, they began the conflict annihilating chattel slavery in the United States.

On August 30, 1877, a monument was unveiled at Osawatomie, “In memory of the heroes who fell in defense of freedom.” The John Brown Memorial Association erected the monument. Some years later, the Women’s Relief Corps of Kansas started a movement to have the battlefield of Osawatomie set apart as a public park. The field was purchased on May 13, 1909, and on August 31, 1910, the park was dedicated to imposing ceremonies, ex-President Roosevelt being the orator of the occasion. Besides these recognitions of Brown’s bravery, the Kansas legislature of 1895 passed a resolution requesting the authorities in charge of the United States statuary hall at Washington to permit the Lincoln Soldiers’ and Sailors’ National Monument association to place a statue of John Brown in the hall, but nothing farther came of the movement.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2023.

Also See:

Bleeding Kansas & the Missouri Border War

Slavery – Cause and Catalyst of the Civil War

African-Americans – From Slavery to Equality

The Underground Railroad – Flight to Freedom

About the Article: This above text is based on information in the book Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Volume I, edited by Frank W. Blackmar, A.M. Ph. D.; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912. The text is not verbatim and has been edited for readability, errors, and updates.