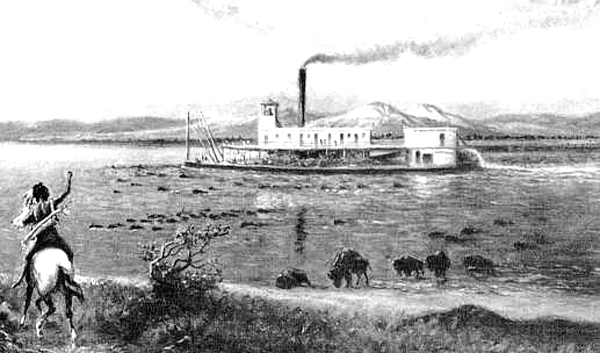

Tulsa, Oklahoma, amid Indian Territory, was first settled by Native Americans in 1836 when they were forcibly made to relocate along the infamous Trail of Tears. The Creek, Seminole, Cherokee, Quapaw, Seneca, Shawnee, and other tribes were all made to surrender their lands east of the Mississippi River after the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830.

Each of the larger tribes was given extensive land holdings, and the Indians began new lives as farmers, trappers, and ranchers. For many, the journey ended beneath the branches of the Council Oak Tree, located on the east side of the Arkansas River.

Some called their settlement Tallahassee, while others used the Creek Indian word “Tulsy,” which meant “old town.” For the next 25 years, they would lead a peaceful life in a primarily untamed wilderness with only a few white settlers.

In 1846, Lewis Perryman, who was part Creek Indian, built a log cabin trading post near what is now 33rd Street and South Rockford Avenue. Perryman’s business was quite successful in the rugged frontier until the Civil War, when many residents fled the area.

When the war broke out, the United States abandoned Indian Territory, sending its troops to war against the Confederate forces. The Creek Indians were torn as to which side to support. Many believed they should move north to Kansas, where they could seek protection. However, when they gathered their families and possessions, a force of Texas Cavalry and Confederate Indians attacked them. The Battle of Round Mountain was fought northwest of Tulsa, where the Cimarron River flows into the Arkansas River. Two other battles were fought north of Tulsa, including the Chustenahlah and Chursto-Talasah. The surviving Union Indians moved into Kansas near the Fort Scott area.

Eventually, the Creek Indians enlisted 1,575 men in the Confederate armies and 1,675 men in the Union forces. After the end of the Civil War, the Creek Indians returned to their homes in the Tulsa area. A United States census taken in 1867 showed that the Tulsa area had a population of 264 Creek.

After the Civil War, numerous outlaws began to take refuge in Indian Territory, which was not yet subject to any white man’s jurisdiction. Wrecking the relative peace of the civilized tribes in the area, Indian Territory soon became known as a very bad place, where desperadoes thought the laws did not apply to them, and terror reigned.

Attempting to tame the wild frontier, President Grant appointed Judge Isaac Parker to rule over the federal district court for the Western District of Arkansas in Fort Smith. This district had jurisdiction over the Indian Territory, and when Parker’s tenure began in 1875, he quickly enforced the law against the many criminals who had taken over Oklahoma. Before long, his efforts would earn him the nickname of “The Hanging Judge” as order was restored to the area.

As more and more white settlers began to move into Indian Territory, the government would break its “permanent” arrangement with the Native Americans. The tribes were forced to accept several new treaties, which further limited the land each held.

In the fall of 1878, the Post Office Department extended its service from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to the Sac and Fox agency in Indian Territory, where a post office was located inside the Perryman Ranch.

Another post office was officially established on March 25, 1879, near what would later become 41st Street and Trenton Avenue in Tulsa. Josiah Perryman became the first postmaster to the town’s 200 residents.

White settlers continued to push into the territory, and in 1882, the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad extended its line to Tulsa to serve the cattle business. A stockyard, with cattle-loading pens and chutes, was built near the tracks, and cattle were driven from the Indian Nations and Texas to be shipped to Northern and Eastern markets.

In no time, the railroad surveyor began to lay out several streets near the railroad tracks. In the beginning, because Tulsa was located in the Creek Nation, it had no legal government or taxes, no public schools, water systems, or street regulations. Tulsa was considered a wide-open town.

Tulsa, Oklahoma, 1896

In the spring of 1883, the post office was moved from the Perryman ranch to the Perryman store, located on what would later become the southwest corner of First and Main Streets. Later, when J.M. Hall was appointed to succeed Josiah Perryman as Postmaster in December 1885, Mr. Hall moved the office to the Hall Brothers’ Store on the west side of Main Street just south of the Frisco tracks.

In 1889, the unassigned lands in Indian Territory were opened to white settlers, and the flood of people was soon nicknamed the “boomers.”

In 1895, a Federal Judge of the first United States court in Indian Territory ruled that Tulsa had the right to incorporate. Tulsa’s business leaders immediately got together to draw a petition for incorporation. Though it took some time, Tulsa, with its population of 1,100 residents, was incorporated on January 18, 1898.

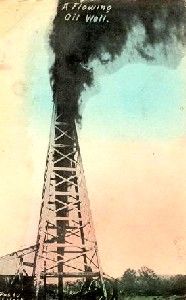

Tulsa Oil Well Postcard-1910

With the discovery of oil in 1901, Tulsa changed from a cow town to a boomtown. At the nearby community of Red Fork, a giant oil deposit was found, and wildcatters and investors began to flood the city of Tulsa, bringing along their families and settling in. New neighborhoods were soon established on the north side of the Arkansas River, and the town began to spread out in all directions from downtown.

Four years later, in 1905, a new, even larger oil discovery was made in nearby Glenn Pool that would later lead to Tulsa’s golden age of the 1920s and its title as the “Oil Capital of the World.” Many early oil companies chose Tulsa for their home base.

By 1920, Tulsa was called home to almost 100,000 people and 400 different oil companies. The booming town boasted two daily newspapers, four telegraph companies, more than 10,000 telephones, seven banks, 200 attorneys, more than 150 doctors, and numerous other businesses.

Though the 1920s looked promising for the burgeoning city, it would soon see one of the most gruesome and devastating race riots in U.S. history.

Tulsa Race Riot

The whole thing began on May 30, 1921, when Dick Rowland, a black shoe-shine boy, was accused of assaulting Sarah Page, an elevator operator in the Drexel Building at Third and Main. Page claimed that Rowland grabbed her arm, causing her to flee in panic. A clerk at a nearby store insisted that Rowland had tried to rape Page. Accounts of the incident circulated among the city’s white community during the day and became more exaggerated with each telling.

Street by street, block by block, the white invaders moved northward across Tulsa’s African-American district, looting homes and setting them on fire. Photo courtesy Department of Special Collections, McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa.

Tulsa police arrested Rowland the following day and began an investigation. Following Rowland’s arrest on May 31, 1921, the Tulsa Tribune printed a story that Rowland had attacked her, scratching her hands and face and tearing her clothes. In the same newspaper, that day was an editorial that stated that a hanging was planned for that night.

Tightly in the grip of the Ku Klux Klan, Tulsa wasted no time in forming a lynch mob that evening around the courthouse intent upon the execution of Dick Rowland. To stave off the lynch mob, the sheriff and his men were forced to barricade the top floor to protect their prisoner.

A group of blacks also converged around the courthouse in an attempt to defend Rowland. When a white man in the crowd confronted an armed black man attempting to wrest the gun from him, a scuffle ensued, and the white man was killed. Immediately, a riot began.

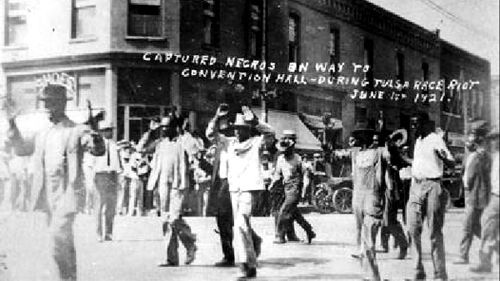

While the authorities detained a handful of white rioters, most black Tulsa

soon found themselves led away at gunpoint and held under guard. Photo courtesy Department of Special Collections, McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa.

The outnumbered blacks began retreating to the Greenwood Avenue business district while truckloads of whites set fires and shot them on sight. Black Tulsa was looted and burned by white rioters in the next day’s early morning. The Greenwood District, known nationally as “Black Wall Street” for its economic success, was a particular target.

Twenty-four hours after the violence erupted, it ceased. In the wake of the violence, 35 city blocks lay in charred ruins, over 800 people were treated for injuries, and almost 1,400 homes were destroyed. The losses of businesses included two theaters, three hotels, more than a dozen restaurants, several churches, and a hospital. Estimates of the dead range up to 300.

After the governor declared martial law, the National Guard troops arrived in Tulsa. They began to round up more than 6,000 black people, placing them in various internment centers such as the baseball stadium, the Convention Hall, and the Fairgrounds. Though the violence had ceased by the next day, many interred were kept for up to eight days.

After this terrible tragedy, dozens of black families left for more peaceful cities. Only a single block of the original buildings remains in the area today.

In the meantime, Tulsa continued to grow as more and more oil fields were found. As automobiles arrived, the mud-filled streets turned to brick, and electric trolleys followed the neighborhoods as they developed further and further from downtown.

The lack of a good water supply was Tulsa’s greatest domestic problem, which was solved when construction on the Spavinaw Dam began in 1922. The Dam and Lake Spavinaw State Park continue to provide water to the Tulsa area today and boating, fishing, picnicking, and camping.

Tulsa at the Center of the Creation of America’s Mother Road

This picture of the Meadow Gold Sign in Tulsa, Oklahoma, was taken on June 13, 2004, just three days before it was taken down. It was later moved down the street and is part of a city park. Photo by David Alexander.

Spawned by the rapidly changing demands of America, entrepreneurs Cyrus Avery of Tulsa, Oklahoma, and John Woodruff of Springfield, Missouri, conceived of the grand idea of linking Chicago to Los Angeles and began lobbying efforts to promote a new highway. The federal government finally pledged to link small town U.S.A. with metropolitan capitals in the summer of 1926 and designated the road as Highway 66.

Aviation also became an important part of the city’s economy, with a municipal airport and the Spartan Aircraft Company established in 1928. During this year, the Oklahoma City Oil Field was discovered and began to produce enormous quantities of oil. This field, combined with the plentiful supply of petroleum from eastern Oklahoma, overwhelmed demand during the early years of the Depression.

During the early 1930s, growth in Tulsa, like many places across the United States, came almost to a complete halt. Few projects were built, and construction stopped on Route 66.

However, in 1933, thousands of unemployed men were put back to work, and road gangs paved the final stretches of the Mother Road. By the mid-1930s, construction picked up, and small houses were built at the city limits’ edge. Soon, the streetcar lines were replaced by the automobile and bus lines.

By 1938, the 2,300-mile super-highway Route 66 was continuously paved from Chicago to Los Angeles, and Tulsa saw the beginnings of numerous cafes, service stations, and motels springing up along the road.

When World War II broke out, Tulsa’s oil industries were converted to defense purposes, and the 1940s brought another period of growth for Tulsa. Many aviation industries converted their factories to accommodate the war effort, and defense workers poured into the city.

After World War II, an increase in offshore drilling operations affected the petroleum industry in Tulsa. Fortunately, the aircraft and aerospace industry was beginning to blossom, and today, there are more than 300 aviation-related companies in the city.

After World War II, an increase in offshore drilling operations affected the petroleum industry in Tulsa. Fortunately, the aircraft and aerospace industry was beginning to blossom, and today, there are more than 300 aviation-related companies in the city.

On April 13, 1949, Tulsa hosted one of its biggest events when the Movie “Tulsa” premiered in the town that carried its name. The celebration featured a parade, which attracted over 100,000 people and featured Susan Hayward, Robert Preston, and Chill Wills. The movie was directed by Stuart Heisler and starred Susan Hayward, Robert Preston, Pedro Armendariz, Chill Wills, Ed Begly, Harry Shannon, Jimmy Conlin, and Paul E. Burns. The movie was about a rancher’s daughter who fought a one-woman war in an oil field country. Ultimately, the heroine won the struggle and built an oil empire. The movie was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Special Effects.

Another means of transportation came to Tulsa in 1970 when the Port of Catoosa opened. This linked Tulsa with the rest of the world via navigation to the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. The Tulsa Port of Catoosa is one of the largest, most inland river ports in the United States!

Today, Tulsa is the second-largest city in Oklahoma, with a population of nearly 400,000. Threads of its Native American heritage, oil boom days, and icons of Route 66 are still visible throughout the modern city.

Many sites are still along the old route if you’re traveling the Mother Road through Tulsa. Old motels dot the streets of 10th, 11th, and Southwest Boulevard. The downtown area has many art deco buildings, including the Warehouse Market at 925 South Elgin Avenue. The Warehouse Market was built in 1929, with bright colored terra cotta tiles enticing people to the farmer’s market. The depression closed it down, but later, it was reopened as the Club Lido during the Big Band Era. Beginning in 1938, it operated as a grocery store until the late 1970s, when it was abandoned and eventually boarded up. In the mid-1990s, the property was sold and was slated to be torn down until the Tulsa Preservation Commission stepped in and saved the face and tower of the original building.

Check out the Art Deco 11th Street Bridge and the magnificent new “East Meets West” statue nearby. In downtown, numerous Art Deco buildings date from the 1920-30s. The first oil well in Tulsa County sits behind Ollies’ Restaurant at 4070 Southwest Boulevard. You can also see many museums, icons, and attractions as you travel the Mother Road through this fine city.

Route 66 leaves Tulsa just south of the I-44 turnpike along Southwest Boulevard. Between Tulsa and Depew, old Route 66 snakes back and forth along I-44 for 40 miles as you pass by several small towns, abandoned motor courts, and old cafes, many of which were built of native stone.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023, with additional edits by Ron Warnick, Route 66 News.

See our Oklahoma Route 66 Photo Gallery HERE

Also See:

Oklahoma Route 66 Photo Gallery