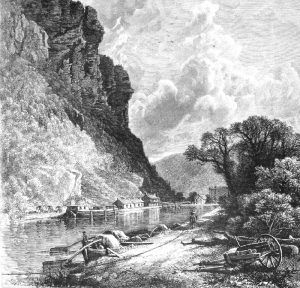

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in the lower Shenandoah Valley of Jefferson County, West Virginia. It is the easternmost town in West Virginia, situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers, where Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia meet.

Historically, Harpers Ferry is best known for John Brown’s Raid on the Armory in 1859 and its role in the Civil War. Today, the lower part of the city forms Harpers Ferry National Historical Park.

The area was first settled in 1733 when a squatter named Peter Stephens made his home near “The Point,” where the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers meet. He established a ferry from Virginia (now West Virginia) to Maryland across the Potomac River. Because of its low elevation, the place was unflatteringly referred to as the “hole.”

Fourteen years later, in 1747, a man named Robert Harper passed through the area while traveling from Maryland to Virginia and recognized the potential for industry provided by the power of the two rivers. He soon paid Stephens 30 British guinea for his squatting rights. Lord Fairfax owned the land, and in April 1751, Harper purchased 126 acres of land from him.

Though a ferry had been operating across the Potomac River for years, the Virginia General Assembly “officially” granted Harper the right to operate a ferry there in 1761. Two years later, the town of “Shenandoah Falls at Mr. Harper’s Ferry” was officially established.

Another man who purchased land from Lord Fairfax was Gersham Keyes, who settled on land about a mile west of Harper. By 1790, Keyes farmed and owned a grist mill, sawmill, blacksmith shop, and two distilleries. Other people also purchased land in the area, and before long, another community formed called Mudfort.

When Thomas Jefferson passed through Harpers Ferry in 1783, he called the site “perhaps one of the most stupendous scenes in nature.”

Two years later, George Washington, working to make improvements along the Potomac River, traveled to Harpers Ferry during the summer of 1785. Wanting the Potomac River to be an avenue of commerce to the west, the establishment of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal began. On his visit, Washington also saw the potential for a new United States armory and arsenal because of its abundant water supply and forestry for wood.

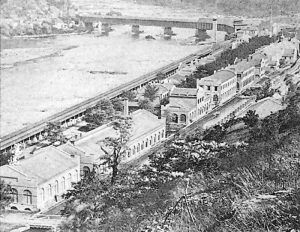

More than a decade later, in 1796, the federal government purchased 125 acres from Robert Harper’s heirs. In 1799, construction began on the United States Armory and Arsenal at Harpers Ferry. It was one of only two such facilities, with the other located in Springfield, Massachusetts. Together, they produced most of the small arms for the U.S. Army.

Harpers Ferry then became an industrial center with more factories in the area. Between 1801 and 1861, they produced more than 600,000 muskets, rifles, and pistols.

In 1803, the Lewis and Clark Expedition was outfitted with weapons for their western journey at Harpers Ferry. On March 16, 1803, Meriwether Lewis arrived with a letter from Secretary of War Henry Dearborn to the Armory superintendent Joseph Perkins to provide the necessary guns and hardware needed for the transcontinental expedition. In addition to arms, ammunition, knives, and repair tools, Lewis also needed the armory to construct a collapsible iron boat frame of his design. The difficulty in construction delayed the expedition’s departure, but it was finally completed, and Lewis departed.

The area was surveyed in 1810, and the settlement of Mudfort was described as having a good tavern, several large stores, a library, and a physician. By 1825, the town population was 270, and the same year, the citizens petitioned the Virginia Assembly to become a town. It was then named Boliver, after South American freedom fighter Simon Bolivar. The petition was granted, and the town of Bolivar came into existence 16 years before Harpers Ferry was granted a charter.

In 1833, the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal reached Harpers Ferry, linking it with Washington, D.C. A year later, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad began service through the town.

By the early 1840s, Harpers Ferry had grown to about 3,000 people, with several businesses, including hotels, saloons, and bawdy houses. In 1851, the town was officially organized with a mayor, recorder, and nine town councilmen.

While the armory in Harpers Ferry was a large part of the area’s economic development, most of the land was agricultural, with wheat and corn as primary crops. The people of Harpers Ferry were employed in manufacturing, while Bolivar was primarily called home to farmers and merchants.

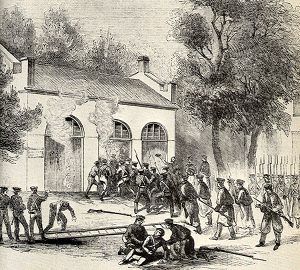

On October 16, 1859, abolitionist John Brown led 21 men on a federal armory and arsenal raid at Harpers Ferry. Brown, who called himself the “Commander in Chief” of the “Provisional Army of the United States,” along with five black and 16 white men, hoped to secure the weapons, arm the slaves, and start a revolt across the South.

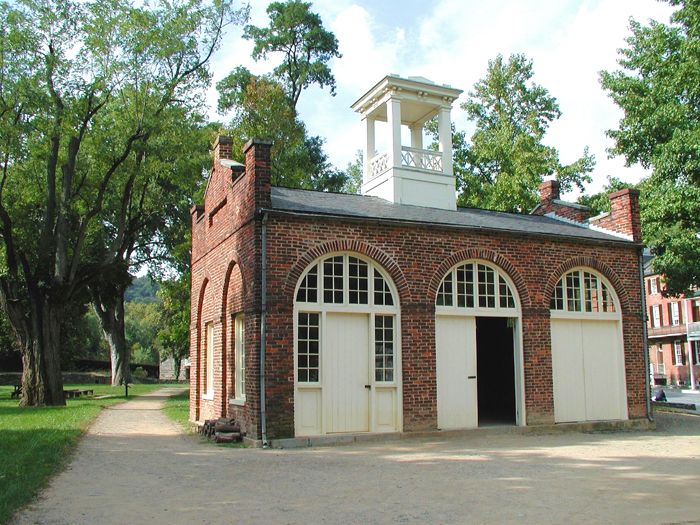

Brown and his men were able to overrun the arsenal. Still, the following day, they were surrounded by townspeople, and soon, a company of U.S. Marines, led by Colonel Robert E. Lee and Lieutenant J. E. B. Stuart, arrived. In the meantime, Brown and his men were holed up in an Armory guard and fire engine house. On the morning of October 19, the soldiers overran Brown and his followers, and in the battle, ten of Brown’s men were killed, including two of his sons. Afterward, the engine house became known as “John Brown’s Fort.”

John Brown, who had been wounded during the battle, was then tried by the state of Virginia for treason and murder. He was found guilty on November 2, 1859, and the 59-year-old abolitionist went to the gallows a month later on December 2.

Before his execution, he handed his guard a slip of paper that read:

“I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”

It was a prophetic statement. Although the raid failed, it inflamed the tensions between the North and South and brought the nation closer to the Civil War.

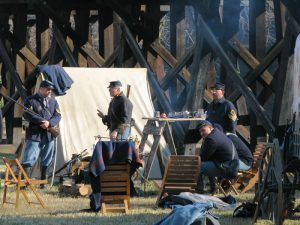

When the Civil War began, it wasn’t good for the people of Harpers Ferry. Because of its strategic location along the rivers and the railroads, the town changed hands between the North and the South several times between 1861 and 1865. Situated at the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley, both Union and Confederate troops moved through Harpers Ferry frequently.

On April 18, 1861, the Virginia Militia marched on Harpers Ferry, and the Federal soldiers torched the U.S. Armory and Arsenal, destroying over 15,000 weapons to keep them out of enemy hands. Ten days later, on April 28, Colonel Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson took command of the town. Over the next seven weeks, all machinery and tools from the armory were removed and shipped to Richmond, Virginia, and Fayetteville, North Carolina, to produce weapons for the Confederacy.

By September 1862, Harpers Ferry was in the hands of the Union, and the Battle of Harpers Ferry occurred between September 12-15, 1862, after General Robert E. Lee found that the Union soldiers had not retreated during his Maryland Campaign. He then sent his Confederate forces to take the city, which was on his supply line and could control one of his possible retreat routes. The battle between Commander Dixon S. Miles of the Union and Major General “Stonewall” Jackson resulted in a massive Confederate victory. With 12,419 Federal troops captured by Jackson, the surrender at Harpers Ferry was the largest surrender of U.S. military troops of the Civil War. It was a dramatic prelude to the great Battle at Antietam, Maryland, that ended the first Southern invasion of the North.

During the Civil War, the former armory guard and fire engine house, known as the John Brown Fort, was used as a prison, a powder magazine, and a quartermaster supply house. Though people broke off pieces of brick and wood from the fort as souvenirs, amazingly, it was never destroyed and was the only Armory building to escape destruction during the Civil War.

After the war, people began to return and rebuild. Still, Harpers Ferry would never again be the industrial center that had maintained its prosperity before the Civil War and its population dropped.

In 1865, a school for freedmen was established in the war-torn building of the former U.S. Armory Paymaster’s quarters. With the help of philanthropic Baptists from New England, the school’s initial purpose was to educate former slaves and train black teachers. Over the following years, the school developed into a black college that operated until 1955.

During the post-Civil War years, the towns of Bolivar and Harpers Ferry were united as one local governing entity. Later, in 1872, they were divided again.

In 1870, floods damaged most buildings along the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers. More floods in later years effectively ended all industrial production in the area. It then became a sleepy little town that was primarily based on farming.

In 1891, the John Brown Fort was sold, dismantled, and transported to Chicago, Illinois, where it was displayed a short distance from The World’s Columbian Exposition. However, it was dismantled again after attracting very few visitors and left on a vacant lot. Three years later, however, it was saved in 1894 by Washington, D.C., journalist Kate Field, who had a keen interest in preserving the memorabilia of John Brown. She soon spearheaded a campaign to return the fort to Harpers Ferry.

With a resident’s donation of land and the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad’s offer to ship the disassembled fort back to Harpers Ferry free of charge, it was rebuilt about three miles outside of town on a bluff overlooking the Shenandoah River.

In 1903, the Storer College began its own fundraising drive to acquire John Brown’s Fort and purchased it in 1909. It was then moved to the Storer College campus and was used as a museum.

By the 1940s, much of the lower town of Harpers Ferry was deteriorating, and in 1944, it was established as the Harpers Ferry National Monument due to its many historical events.

In 1954, a U.S. Supreme Court decision declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. Immediately after the ruling, West Virginia withdrew its financial support from Storer College. The following year, Storer College closed its doors forever.

In 1960, the National Park Service acquired John Brown’s Fort building, which was moved back to the Lower Town in 1968.

In 1963, Harpers Ferry National Monument became Harpers Ferry National Historical Park. The park was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in October 1966.

The entire town became a Historic District in 1979, providing additional protection for the town’s heritage. Since 2003, the Harpers Ferry Historic Town Foundation has tried to preserve and beautify the town.

The park, which covers almost 4,000 acres, includes the historic town of Harpers Ferry, John Brown’s Fort, a visitor center, many buildings that once belonged to Storer College, and Civil War battle sites, including Bolivar Heights, one of the most important Civil War battlefields in West Virginia and the site of the largest surrender of United States troops during the Civil War.

North of the park and across the Potomac from Harpers Ferry is the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park. The canal, which operated from 1828 to 1924, provided a vital waterway link with areas up and downstream before and during the early years after the railroad’s arrival.

Aside from the extensive historical interests of the park, recreational opportunities include fishing, boating, whitewater rafting, and hiking, with the Appalachian Trail passing right through the park. The park adjoins the Harpers Ferry Historic District and two other National Register of Historic Places locations: St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church and the B & O Railroad Potomac River Crossing.

The “town” actually encompasses the two villages of Harpers Ferry and Bolivar, where numerous museums, shops, restaurants, and local outfitters for recreational opportunities can be found.

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park is eight miles east of Charles Town, West Virginia, and 20 miles southwest of Frederick, Maryland.

More Information:

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park

171 Shoreline Drive

P.O. Box 65

Harpers Ferry, West Virginia 25425

304-535-6029

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2024.