By Emerson Hough in 1905

The world will never see another California. Great gold stampedes there may be but under conditions far different from those of 1849. Transportation has been so developed; travel has become so swift and easy that no section can now long remain segregated from the rest of the world. No corner of the earth may not now be reached with a swiftness impossible in the days of the great rush to the Pacific Coast. The whole structure of civilization, itself based upon transportation, goes swiftly forward with that transportation, and the tent of the miner or adventurer finds immediately erected by its side the temple of the law.

It was not thus in those early days of our Western history. The law was left far behind by geography and wilderness travel. Thousands of honest men pressed on across the plains and mountains inflamed, it is true, by the madness of the lust for gold, but carrying at the outset no wish to escape from the watchfulness of the law. With them went equal numbers of those eager to escape all restraints of society and law, men intending never to aid in the uprearing of the social system in new wildlands.

Both these elements, the law-loving, and the law-hating, as they advanced farther and farther from the staid world, they had known, noticed the development of a strange phenomenon: that law they had left behind them waned in importance with each passing day. The standards of the old home changed, even as customs changed. A week’s journey from the settlements showed the argonaut a new world. A month hedged it about to itself, alone, with ideas and values of its own and independent of all others. A year sufficed to leave that world as distinct as though it occupied its own planet. For that world, the divine fire of the law must be re-discovered, evolved, nay, evoked fresh from chaos even as the savage calls forth fire from the dry and sapless twigs of the wilderness.

All ideas and principles were based upon new conditions in the gold country. Precedents did not exist. Man had gone savage again, and it was the beginning. Yet this savage, willing to live like a savage in a land which was one vast encampment, was the Anglo-Saxon savage and therefore carried with him that chief trait of the American character, the principle that what a man earns—not what he steals, but what he earns — is his and his alone. This principle sowed in the ground forbidding, and unpromising was the seed of the law, out of which has sprung the growth of a mighty civilization fit to be called an empire of its own. Under such conditions, the growth and development of law offered phenomena not recorded in the history of any other land or time.

In the first place, and even while in transit, men organized for self-protection, and in this necessary act, law-abiding and criminal elements united. After arriving at the scenes of the goldfields, such organization was forgotten; even the parties that had banded together in the Eastern states as partners rarely kept together for a month after reaching the region where luck, hazard, and opportunity, inextricably blended, appealed to each man to act for himself and with small reference to others. The first organizations of the mining camps were those of the criminal element. The organization of the law and order men presently met them. Hard upon the miners’ law came the regularly organized legal machinery of the older states, modified by local conditions and irretrievably blended with a politics more corrupt than any known before or since. Men were busy picking up raw gold from the earth and paid little attention to courts and government. The law became an unbridled instrument of evil. Judges of the courts openly confiscated the property of their enemies or sentenced them with no reference to the principles of justice, with as great disregard for life and liberty as was ever known in the Revolutionary days of France. Against this manner of government presently arose the law-abiding and the justice-loving organizations, and these took the law into their own stern hands. The executive officers of the law, the sheriffs and constables, were in league to kill and confiscate. Against these, the new agency of the existing law made war, constituting themselves into an arm of essential government, and openly called themselves vigilantes.

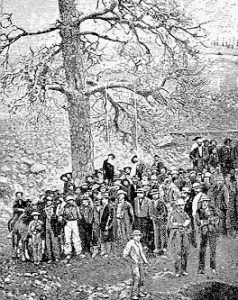

In turn, criminals used the cloak of the vigilantes to cover their deeds of lawlessness and violence. The vigilantes purged themselves of the false members and carried their title of shameful conduct, the “stranglers,” with unconcern or pride. They grew in numbers, the love of justice their lodestone, until at one time, they numbered more than five thousand in the city of San Francisco alone and held that community in the grip of lawlessness, or law, as you shall choose to term it. They set at defiance the state’s chief executive, erected an armed castle of their own, seized upon the arms of the militia, and defied the government of the United States and even the United States Army. As you shall choose to call them, they were criminals or great and noble men. Seek as you may today, you will never know the full roster of their names, although they made no concealment of their identity, and no one, to this day, has ever been able to determine who took the first step in their organization.

They began their labors in California at a time when there had been more than 2,000 murders — 500 in one year — and not five legal executions. Their task included the erection of a fit structure of the law and, incidentally, the destruction of a corrupt and unworthy structure claiming the title of the law.

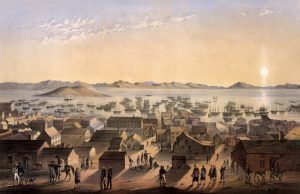

In this strange, swift panorama, there is all the story of the social system, all the picture of the building of that temple of the law which, as Americans, we now revere or, at times, still despise and desecrate. At first, the average gold seeker concerned himself little with the law because he intended to make his fortune quickly and then hasten back East to his former home; yet, as early as the winter of 1849, there was elected a legislature that met at San Jose, a Senate of 16 members and an Assembly of 36. In this election, the new American vote was in evidence.

The miners had already tired of the semi-military phase of their government and had met and adopted a state constitution. The legislature enacted 140 new laws in two months and abolished all former laws; then, satisfied with its labors, it left the enforcement of the laws, in the good old American fashion, to whomsoever might take an interest in the matter. This is our custom even today. Our great cities of the East are practically all governed, so far as they are governed at all, by civic leagues, civic federations, citizens’ leagues, businessmen’s associations—all protests at non-enforcement of the law. This protest in ’49 and on the Pacific Coast took a sterner form.

At one time, the city of San Francisco had three separate and distinct city councils, each claiming to be the only legal one. Despite the new state organization, the law was much a matter of going as you please. Under such conditions, it was no wonder that outlawry began to show its head in bold and well-organized forms. A party of ruffians, who called themselves the “Hounds,” banded together to run all foreigners out of the rich camps and take their diggings over for themselves. Several Chileans were beaten or shot, and their property was confiscated or destroyed. This was not in accordance with the saving grace of American justice, which was devoted to a man that he had earned. A counter organization was promptly formed, and the “Hounds” were confronted with 200 “special constables,” each with a good rifle. A mass meeting sat as a court, and 20 of the “Hounds” were tried; 10 received sentences that were never enforced but had the desired effect. So now, while far to the east, Congress was hotly arguing the question of the admission of California as a state, she was beginning to show an interest in law and justice when aroused thereto.

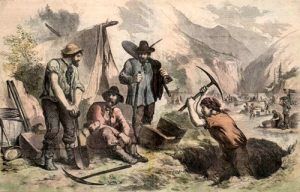

It was difficult material to build a civilized community. The hardest population of the entire world was there; men savage or civilized by tradition, heathen or Christian once at least, but now all Californian. Wealth was the one common thing. The average daily return in mining work ranged from $20 to $30, and no man might tell when a blow might make his fortune of a pick. Some nuggets of gold weighing 25 pounds were discovered. Men picked pure gold from the rock crevices with a spoon or knifepoint in certain diggings. As to values, they were guessed at, the only currency being gold dust or nuggets. Prodigality was universal. All the gamblers of the world met in the vulture concourse. There was little in the way of home; of women, almost none. Life was as cheap as gold dust. Let those who liked to bother about statehood, government, and politics; the average man was too busy digging and spending gold to trouble over such matters. The most shameless men were those found in public office.

Wealth and commerce waxed great, but law and civilization languished. The times were ripening for the growth of some system of law that would offer proper protection for life and property. The measure of this need may be seen from the gold production figures. From 1848 to 1856, California produced between 500-600 million dollars in pure gold. What wonder the courts were weak, and the Vigilantes became strong! There were in California three distinct Vigilante movements, those of 1849, the San Francisco Vigilantes of 1851, and the San Francisco Vigilantes of 1856, the earliest applying instead to the outlying mining camps than to the city of San Francisco. In 1851, seeing that the courts did not attempt to punish criminals, a committee was formed that enforced respect for the principles of justice, if not of law. On June 11, they hanged John Jenkins for robbing a store. A month later, they hanged James Stuart for murdering a sheriff. In August of the same summer, they took out of jail and hanged Whittaker and McKenzie, Australian ex-convicts, whom they had tried and sentenced but who had been rescued by the law officers. Two weeks later, this committee disbanded. They paid no attention to the many killings going on over land titles and the like but confined themselves to punishing men who had committed intolerable crimes. Theft was as serious as murder, perhaps more so, in the creed of the time and place. The list of murders reached appalling dimensions. The times were sadly out of joint. The legislature was corrupt, graft was rampant — though unknown by that name — and the entire social body was restless, discontented, and uneasy. Politics had become a fine art. The judiciary, lazy and corrupt, was held in contempt. The courts’ dockets were full, and little was done to clear them effectively. Criminals did as they liked and went un-whipped of justice. It was indeed a day of violence and license.

Once more, California’s sober and law-loving men sent word abroad, and again the vigilantes assembled. In 1853, they hanged two Mexicans for horse stealing and a bartender who had shot a citizen near Shasta. At Jackson, they hanged another Mexican for horse stealing, and at Volcano, in 1854, they hanged a man named Macy for stabbing an old and helpless man. Vengeance was very swift in this instance, for the murderer was executed within half an hour after his deed. The haste caused certain criticism when, in the same month, one Johnson was hanged for stabbing a man named Montgomery at Iowa Hill, who later recovered. In Los Angeles, three men were sentenced to death by the local court, but the Supreme Court issued a stay for two of them, Brown and Lee. The people asserted that all must die together, and the mayor agreed. The third man, Alvitre, was hanged legally on January 12, 1855. On that day, the mayor resigned his office to join the vigilantes. Brown was taken out of jail and hanged despite the decision of the Supreme Court. The people were out-running the law. That same month, they hanged another murderer for killing the treasurer of Tuolumne County. They hanged three more cattle thieves in Contra Costa County in the following month and followed this by hanging a horse thief in Oakland. A more significant affair threatened the following summer when 36 Mexicans were arrested for killing a party of Americans. For a time, it was proposed to hang all 36, but sober counsel prevailed, and only three were hanged; this after a formal jury trial. Unknown bandits were waylaid and killed Isaac B. Wall and T. S. Williamson of Monterey, and, that same month, U.S. Marshal William H. Richardson was shot by Charles Cora in the streets of San Francisco. The people grumbled. There was no certainty that justice would ever reach these offenders. The state’s reputation was ruined, not by the acts of the vigilantes but by those of unscrupulous and unprincipled men in the office and upon the bench. Gamblers, ruffians, and thugs ran the government. The good men of the state began to prepare for a general movement of purification and the installation of actual law. The great Vigilante movement of 1856 was the result.

The immediate cause of this last organization was the murder of James King, editor of the Bulletin, by James P. Casey. Casey, after shooting King, was hurried off to jail by his friends and was protected by a display of military force. King lingered for six days after he was shot, and the state of public opinion was ominous. Cora, who had killed Marshal Richardson, had never been punished, and there seemed no likelihood that Casey would be. The local press was divided. The religious papers, the Pacific and the Christian Advocate, both openly declared that Casey ought to be hanged. The clergy took up the matter sternly, and one minister of the Gospel, Reverend J. A. Benton of Sacramento, gave utterance to this remarkable but well-grounded statement: “A people can be justified in recalling delegated power and resuming its exercise.” Before we hasten to criticize sweepingly under the term “mob law” such work as this of the vigilantes, it will be well for us to weigh that utterance and to apply it to conditions of our times; today is almost as dangerous to American liberties as were the wilder days of California.

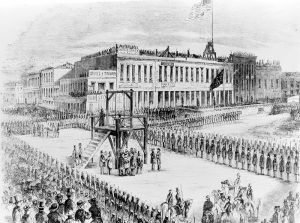

Now, summoned by some unknown command, armed men appeared in the streets of San Francisco, twenty-four companies in all, with perhaps fifty men in each company. The vigilantes had organized again. They brought a cannon and placed it against the jail gate and demanded that Casey be surrendered to them. There was no help for it, and Casey went away handcuffed to face a court where political influence would mean nothing. An hour later, the murderer Cora was taken from his cell and was hastened away to join Casey in the headquarters building of the vigilantes. A company of armed and silent men marched on each side of the prisoner’s carriage. The two men were tried in a formal session of the Committee, each having counsel and all evidence being carefully weighed.

King died on May 20, 1856, and was buried with popular honors on May 22. A long procession of citizens followed the body to the cemetery. A popular subscription was started, and over $30,000 was raised for the benefit of his widow and children in a brief time. When the long procession filed back into the city, it was to witness the bodies of Casey and Cora swinging from a beam projecting from a window of Committee headquarters.

The Vigilante Committee now arrested two more men, not for a capital crime, but for one which lay back of a long series of capital crimes — the stuffing of ballot boxes and other election frauds. These men were Billy Mulligan and the prize-fighter known as Yankee Sullivan. Although advised that he would have a fair trial and that the death penalty would not be passed upon him, Yankee Sullivan committed suicide in his cell. Naturally enough, the entire party of lawyers and judges was arrayed against the Committee. Judge Terry of the Supreme Court issued a writ of habeas corpus for Mulligan. The Committee ignored the sheriff who was sent to serve the writ. They cleared the streets in front of headquarters, established six cannons in front of their rooms, put loaded swivels on top of the roof, and mounted a guard of 100 riflemen. They brought bedding and provisions to their quarters, mounted a huge triangle on the roof for a signal to their men all over the city, arranged the interior of their rooms in the form of a court, and, in short, set themselves up as the law, openly defying their own Supreme Court of the state. So far from being afraid of the vengeance of the law, they arrested two more men for election fraud, Charles P. Duane and “Woolly” Kearney. All their prisoners were guarded in cells within the headquarters building.

The opposition to the Committee now organized in turn under the name of the “Law and Order Men” and held a public meeting. This was numerously attended by members of the Vigilante Committee, whose books were now open for enrollment. Not even the criticism of their friends stayed these men in their resolution. They went even further. Governor Johnson proclaimed to them to disband and disperse. They paid no more attention to this than they had to Judge Terry’s writ of habeas corpus. The governor threatened them with the militia, but it was not enough to frighten them. General Sherman resigned his command in the state militia and counseled moderation at a dangerous time. Many militia turned in their rifles to the Committee, which got other arms from harbor vessels and carelessly guarded armories. Halting at no responsibility, a band of the Committee even boarded a schooner carrying down a cargo of rifles from the governor to General Howard at San Francisco and seized the entire lot.

Shortly after this, they confiscated a second shipment that the governor was sending down from Sacramento in the same way, thus seizing the federal government’s property. If there was such a crime as high treason, they committed it openly and without hesitation. Governor Johnson contented himself with drawing up a statement of the situation, which was sent down to President Pierce at Washington, requesting that he instruct naval officers on the Pacific station to supply arms to the State of California, which had been despoiled by certain of its citizens. President Pierce turned over the matter to his attorney-general, Caleb Gushing, who rendered an opinion saying that Governor Johnson had not yet exhausted the state remedies and that the United States government could not interfere.

Little remained for the Committee to show its resolution to act as the State Pro tempore. That little it now proceeded to do by practically suspending the Supreme Court of California. In arresting a witness wanted by the Committee, Sterling A. Hopkins, one of the policemen retained for work by the Committee, was stabbed in the throat by Judge Terry of the Supreme Bench, who was very bitter against all members of the Committee. It was supposed that the wound would prove fatal, and at once, the Committee sounded the call for a general assembly. The city went into two hostile camps, Terry and his friend, Dr. Ashe, taking refuge in the armory where the “Law and Order” faction kept their arms. The members of the Vigilante Committee besieged this place and presently took charge of Terry and Ashe as prisoners. Then, the scouts of the Committee went out after the arms of all the armories belonging to the governor and the “Law and Order” men who supported him, the lawyers and politicians who felt that their functions were being usurped. Two thousand rifles were taken, leaving the opposing party without arms. The entire state was now in the hands of the “Committee of Vigilance,” a body of men, quiet, law-loving, law-enforcing, but technically traitors and criminals. The parallel of this situation has never existed elsewhere in American history.

Had Hopkins died, the probability is that The Committee would have hung Judge Terry, but fortunately, he did not die. Terry lay a prisoner in the cell assigned him at the Committee’s rooms for seven weeks, by which time Hopkins had recovered from the wound given to him by Terry. The case became one of national interest, and tirades against “the Stranglers” were not lacking, but the Committee went on enrolling men. It did not open its doors for its prisoners, although the appeal was made to Congress on Terry’s behalf- an appeal which was referred to the Committee on Judiciary and so buried. Terry was finally released, much to the regret of many of the Committee, who thought he should have been punished. The executive committee called together the board of delegates and issued a statement showing that death and banishment were the only optional penalties.

Death they could not inflict because Hopkins had recovered, and banishment they thought impractical, as it might prolong discussion indefinitely and enforce a longer term in service than the Committee cared for. It was the earnest wish of all to disband at the first moment when they considered their state and city fit to take care of themselves, and the sacredness of the ballot box was again insured. They had arrayed themselves against the federal government to assure this latter fact, as certainly, they had against the state government.

The Committee now hanged two more murderers — Hetherington and Brace — the former a gambler from St. Louis, the latter a youth of New York parentage, 21 years of age, but hardened enough to curse volubly upon the scaffold. By the middle of August 1856, they had no more prisoners in charge and were ready to turn the city over to its system of government. Their report, published in the following fall, showed they had hanged four men and banished many others, besides frightening out of the country a large criminal population that did not tarry for arrest and trial.

If the opinion was divided to some extent in San Francisco, where those stirring deeds occurred, the sentiment of the outlying communities of California was almost a unit in favor of the Vigilantes, and their action received the sincere flattery of imitation as half a score of criminals learned to their sorrow on impromptu scaffolds. There was no large general organization in any other community, however. After a time, some of the banished men came back, and many damage suits were argued later in the courts, but small satisfaction came to those claimants, and few men who knew of the deeds of the “Committee of Vigilance” ever cared to discuss them. Indeed, it was certain that any man who served on a Western vigilance committee finished his life with sealed lips. He would have met contempt or something harsher if he had ventured to talk of what he knew.

Political capital was made out of the situation in San Francisco. The “Committee of Vigilance” felt it had concluded its work and was ready to return to civil life. On August 18, 1856, the Committee marched openly in review through the city’s streets, 5,237 men in line, with three artillery companies, 18 cannons, a company of dragoons, and a medical staff of forty-odd physicians. In this body, 150 men served in the old Committee in 1851. After the parade, the men halted, and the assemblage broke up into companies, the companies into groups; and thus, quietly, with no vaunting of themselves and no concealment of their acts, there passed away one of the most singular and significant organizations of American citizens ever known. They did this with the quiet assertion that they would again assemble if their services were needed. They printed a statement covering their actions in detail, showing to any fair-minded man that what they had done was indeed for the good of the whole community, which had been wronged by those whom it had elected to power, those who had set themselves up as masters where they had been chosen as servants.

The “Committee of Vigilance” of San Francisco comprised men from all walks of life and political parties. It had any amount of money it required at its command, for its members were the best and most influential citizens. It maintained quarters unique in their way during its existence, serving as an arms room, a trial court, a fortress, and a prison. It was not a mob but a grave and orderly band of men, and its deliberations were formal and exact, its labors being divided among proper sub-committees and boards. The quarters were kept open day and night, always ready for swift action if necessary. It had an executive committee, which, upon occasion, conferred with a board of delegates composed of three men from each subdivision of the general body. The executive committee consisted of thirty-three members, and its decision was final, but it could not enforce a death penalty except on a two-thirds vote of those present. It had a prosecuting attorney and tried no prisoner without assigning competent counsel to him. It also had a police force with a police chief and a sheriff with several deputies. In short, it took over the government and was indeed the government, municipal and state in one. Recent as was its life, its deeds today are almost forgotten. Though opinion may still be divided in certain quarters, California must not be ashamed of this “Committee of Vigilance.” She should be proud of it, for it was mainly through its un-thanked and dangerous safeguarding of the public interests that California gained her social system of today.

In all the history of American desperadoism and the movements that have checked it, there is no page more worth studying than this from the story of the great Golden State. The moral is a sane, clean, and strong one. The “Committee of Vigilance” creed is one we might well learn today. Its practice would leave us with more dignity of character than we can claim, so long as we content ourselves merely with outcry and criticism, with the sweeping accusation of our unfaithful public servants, and without seeing that they are punished. There is nothing but manhood, freedom, and justice in the covenant of the Committee. That covenant all American citizens should be ready to sign and live up to: “We do bind ourselves each unto the other by a solemn oath to do and perform every just and lawful act for the maintenance of law and order and to sustain the laws when faithfully and properly administered. But we are determined that no thief, burglar, incendiary, assassin, ballot-box stuffer, or another disturber of the peace shall escape punishment, either by quibbles of the law, the carelessness of the police, or a laxity of those who pretend to administer justice.”

What a man earns, that is his—such was the lesson of California. Self-government is our right as a people—that is what the vigilantes said. When the laws failed in execution, then it was the people’s right to resume the power that they had delegated or which had been usurped from them—that is their statement as quoted by one of the ablest of many historians of this movement. The people might withdraw authority when faithless servants used it to thwart justice—that was what the Vigilantes preached. It is a sound doctrine today.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

Go To Next Chapter – The Outlaw Of The Mountains

About the Author: Excerpted from the book The Story of the Outlaw; A Study of the Western Desperado, by Emerson Hough; Outing Publishing Company, New York, 1907. This story is not verbatim as it has been edited for clerical errors and updated for the modern reader. Emerson Hough (1857–1923).was an author and journalist who wrote factional accounts and historical novels of life in the American West. His works helped establish the Western as a popular genre in literature and motion pictures. For years, Hough wrote the feature “Out-of-Doors” for the Saturday Evening Post and contributed to other major magazines.

Other Works by Hough:

The Story of the Outlaw – A Study of the Western Desperado – Entire Text