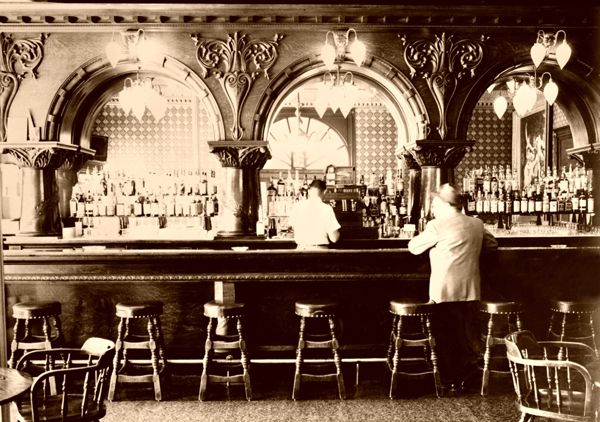

Meeker, Colorado Saloon in 1899

Mammoth Saloon, Goldfield, Arizona by Kathy Alexander

Saloons, Women & Gambling Photo Gallery

“Sometimes too much drink is barely enough.” — Mark Twain

Well, there just ain’t no talkin’ about the Old West, without mentioning the dozens, no hundreds – er, thousands of saloons of the American West. The very term “saloon” itself conjures up a picture within our minds of an Old West icon, complete with a wooden false front, a wide boardwalk flanking the dusty street, a couple of hitchin’ posts, and the always present swinging doors brushing against the cowboy as he made his way to the long polished bar in search of a whiskey to wet his parched throat.

When America began its movement into the vast West, the saloon was right behind, or more likely, ever-present. Though places like Taos and Santa Fe, New Mexico, already held a few Mexican cantinas, they were far and few between until the many saloons of the West began to sprout up wherever the pioneers established a settlement or where trails crossed.

The first place that was actually called a “saloon” was at Brown’s Hole near the Wyoming–Colorado–Utah border. Established in 1822, Brown’s Saloon catered to the many trappers during the heavy fur trading days.

Desert John’s Saloon in Deerlodge, Montana

Saloons were ever popular in a place filled with soldiers, which included one of the West’s first saloons at Bent’s Fort, Colorado, in the late 1820s; or with cowboys, such as Dodge City, Kansas; and wherever miners scrabbled along rocks or canyons in search of their fortunes. When gold was discovered near Santa Barbara, California, in 1848, the settlement had but one cantina. However, just a few short years later, the town boasted more than 30 saloons. In 1883, Livingston, Montana, though it had only 3,000 residents, had 33 saloons.

The first western saloons really didn’t fit our classic idea of what a saloon looks like, but rather, were hastily thrown together tents or lean-to’s where a lonesome traveler might strike up a conversation, where a cowman might make a deal, or a miner or a soldier might while away their off-hours. However, as the settlement became more populated, the saloon would inevitably prosper, taking on the traditional trimmings of the Old West.

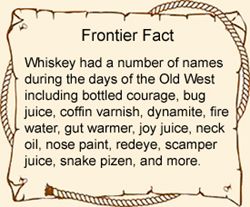

In those hardscrabble days, the whiskey served in many saloons was some pretty wicked stuff made with raw alcohol, burnt sugar, and a little chewing tobacco. No wonder it took on such names as Tanglefoot, Forty-Rod, Tarantula Juice, Taos Lightning, Red Eye, and Coffin Varnish.

Also popular was Cactus Wine, made from a mix of tequila and peyote tea, and Mule Skinner made with whiskey and blackberry liquor. The house rotgut was often 100 proof, though it was sometimes cut by the barkeep with turpentine, ammonia, gunpowder, or cayenne.

The most popular term for the libation served in saloons was Firewater, which originated when early traders were selling whiskey to the Indians. To convince the Indians of the high alcohol content, the peddlers would pour some of the liquor on the fire as the Indians watched the fire begin to blaze.

The most popular term for the libation served in saloons was Firewater, which originated when early traders were selling whiskey to the Indians. To convince the Indians of the high alcohol content, the peddlers would pour some of the liquor on the fire as the Indians watched the fire begin to blaze.

But most western saloon regulars drank straight liquor — rye or bourbon. If a man ordered a “fancy” cocktail or “sipped” at his drink, he was often ridiculed unless he was “known” or already had a proven reputation as a “tough guy.” Unknowns, especially foreigners who often nursed their drinks, were sometimes forced to swallow a fifth of 100 proof at gunpoint “for his own good.”

Saloons also served up volumes of beer, but in those days, the beer was never ice-cold, usually served at 55 to 65 degrees. Though the beer had a head, it wasn’t sudsy as it is today. Patrons had to knock back the beer in a hurry before it got too warm or flat.

It wasn’t until the 1880’s that Adolphus Busch introduced artificial refrigeration and pasteurization to the U.S. brewing process, launching Budweiser as a national brand. Before then, folks in the Old West didn’t expect their beer to be cold, accustomed to the European tradition of beer served at room temperature.

In virtually every mining camp and prairie town, a poker table could be found in each saloon, surrounded by prospectors, lawmen, cowboys, railroad workers, soldiers, and outlaws for a chance to tempt fortune and fate.

Faro was the most popular and prolific game played in Old West saloons, followed by Brag, Three-card-monte, and dice games such as High-low, Chuck-a-luck, and Grand Hazard. Before long many of the Old West mining camps such as Deadwood, Leadville, and Tombstone, became as well known for gunfights over card games as they did for their wealth of gold and silver ore.

Professional gamblers such as Doc Holliday and Wild Bill Hickok learned early to hone their six-shooter skills at the same pace as their gambling abilities. Taking swift action upon the green cloth became part of the gamblers’ code – shoot first and ask questions later.

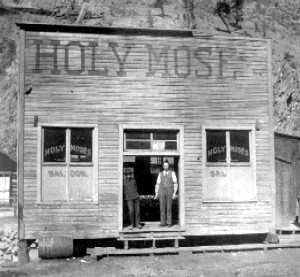

Eventually, there was every type of saloon that one could imagine. There were gambling saloons, restaurant saloons, billiard saloons, dancehall saloons, bowling saloons, and, of course, the ever-present, plain ole’ fashioned, “just drinking” saloons. They took on names such as the First Chance Saloon in Miles City, Montana, the Bull’s Head in Abilene, Kansas, and the Holy Moses in Creede, Colorado. In many of the more populated settlements, these saloons never closed, catering to their ever-present patrons 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Some didn’t even bother to have a front door that would close.

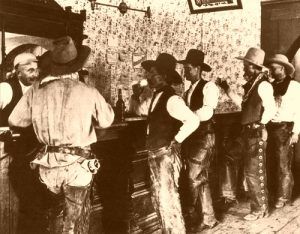

In almost every saloon, one could depend on seeing the long paneled bar, usually made of oak or mahogany and polished to a splendid shine. Encircling the base of the bar would be a gleaming brass foot rail with a row of spittoons spaced along the floor next to the bar. Along the ledge, the saloon patron would find towels hanging so that they might wipe the beer suds from their mustaches. Most saloons included some kind of gambling, including such games as Chuck-A-Luck, Three-Card-Monte, Faro, and usually an ongoing game of poker.

Decorations at these many saloons varied from place to place but most often reflected the customers’ ideals. In the cowtowns of the prairies, one might see steer horns, spurs, and saddles adorning the walls, while in the mountains, a customer would be met by the glazing eyes of taxidermied deer or elk. Often, there was the infamous nude painting of a woman hanging behind the bar.

Holy Moses Saloon, Creede, Colorado, 1890

One question many people ask is whether saloons were really adorned with swinging-style doors. These types of doors called cafe doors, and sometimes referred to as “batwing” doors, were found in many saloons, but not nearly as often as they are depicted in popular movies. In film, there’s just no better door than the swinging door for the hero to burst into and for the bad guys to be tossed out through.

Cafe doors are designed to allow easy passage between two rooms, or from the outside to the inside, by using bidirectional hinges. Shorter than full height, they are situated in the middle of the frame. They were practical because they provided easy access, cut down the dust from the outside, allowed people to see who was coming in and provided some ventilation. Most importantly, it shielded the goings-on in the saloon from the “proper ladies” who might be passing by.

Most saloons, however, had actual doors. Even those with swinging doors often had another set on the outside, so the business could be locked up when closed and to shield the interior from bad weather. On the other hand, some crude saloons didn’t have doors, as they were open 24 hours a day.

The regulars at saloons often acquired calluses on their elbows by prolonged and heavy leaning on the bar. Men of the West usually did not drink alone, nor did they drink at home, and needing each other’s company, there were a lot of regulars at the many saloons. The patrons were a varied lot – from miners to outlaws to gamblers and honest workmen. What they were not — were minorities. Saloons of the West did not welcome other races. Indians were excluded by law. An occasional black man might begrudgingly be accepted, or at least ignored if he happened to be a noted gambler or outlaw. If a Chinese man entered a saloon, he risked his life.

Montana Hotel Saloon, Anaconda, Montana

However, there was one type of “white man” that was also generally not welcome. That was the soldier. There were several reasons for this. Given the makeup of the many men of the West — adventurers, people who “didn’t fit in” in the East, outlaws, and Civil War deserters, they had no respect for the men who “policed the West.” Nor could these independent-minded men respect anyone who was made to “stand at attention” and obey all orders. Finally, for some unknown reason, they blamed the soldier for infecting the parlor house girls with diseases.

Due to the culture at the time, respectable women were also excluded. Unless they were a saloon girl or a “shady lady,” women did not enter saloons, a tradition that lasted until World War I. In retaliation, the ladies were primarily behind the prohibition movement.

These private men of the West were also accustomed to inquiring of another man’s first name only. With their varied and often shady backgrounds, curiosity was considered impolite. Both men’s and women’s pasts were respected and were not inquired about. If and when it was, it could be very unhealthy for the inquirer, who might end up dead in the street in front of the saloon. For instance, one would never ask a rancher the size of his herd, which would be tantamount to asking a man to see their income tax return today.

Another custom was the expected offer to treat the man standing next to you to a drink. If a stranger arrived and didn’t make the offer, he would often be asked why he hadn’t done so. Even worse was refusing a drink, which was considered a terrible insult, regardless of the vile liquor that might be served. On one such occasion at a Tucson, Arizona saloon, a man who refused the offer was taken from bar to bar at gunpoint until “he learned some manners.”

However, if a man came in and confessed that he was broke and needed a drink, few men would refuse him. On the other hand, if he ordered a drink, knowing he couldn’t pay for it, he might find himself beaten up or worse.

Because the saloon was usually one of the first and bigger buildings within many new settlements, it was common that it was also utilized as a public meeting place. Judge Roy Bean and his combination saloon and courtroom were a prime example of this practice. Another saloon in Downieville, California, was not only the most popular saloon in town but also the office of the local Justice of the Peace. In Hays City, Kansas, the first church services were held in Tommy Drum’s Saloon.

Several noted gunmen of the west owned saloons, tended bar, or dealt cards at one time or another. These included such notable characters as Wild Bill Hickok, Bill Tilghman, Ben Daniels, Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, Ben Thompson, Doc Holliday, and many others.

But, most notable among the many saloons of the West was the ever-present violence that was instigated or occurred within these establishments. In 1876, Bob Younger said, “We are rough men and used to rough ways.” Couple that with the public access, flow of potent whiskey, and the general lawlessness of the times, and the saloon was an inevitable powder keg.

There were numerous killings inside of these Old West saloons. Just a few of these included Wild Bill Hickok, who was killed by Jack McCall while playing poker in the No. 10 Saloon in Deadwood, South Dakota.

Bob Ford, Jesse James’ killer, was shot down in his own tent saloon in Creede, Colorado; and John Wesley Hardin was shot and killed from behind on August 19, 1895, in an El Paso, Texas saloon.

Many other acts of violence were instigated in saloons, which wound up with shoot-outs in the street or public hangings after vigilante groups had formed within a saloon.

Dance Hall Girl, 1885

And lest we not forget the saloon or dance-hall girl, whose job was to brighten the evenings of lonely men starved for female companionship. Contrary to what many might think, the saloon girl was very rarely a prostitute – this tended to occur only in the very shabbiest class of saloons. Though the “respectable” ladies considered the saloon girls “fallen,” most of the girls wouldn’t be caught dead associating with an actual prostitute. Their job was to entertain the guests, sing for them, dance with them, talk to them and perhaps flirt with them a bit – inducing them to others in the bar, buying drinks, and patronizing the games.

Not all saloons employed saloon girls, such as in Dodge City’s north side of Front Street, which was the “respectable” side, where guns, saloon girls, and gambling were barred. Instead, music and billiards were featured as the chief amusements to accompany drinking.

Most girls were refugees from farms or mills, lured by posters and handbills advertising high wages, easy work, and fine clothing. Many were widows or needy women of good morals, forced to earn a living in an era that offered few means for women to do so.

Earning as much as $10 per week, most saloon girls also made a commission from the drinks they sold. Whiskey sold to the customer was marked up 30-60% over its wholesale price. Commonly drinks bought for the girls would only be cold tea or colored sugar water served in a shot glass; however, the customer was charged the full price of whiskey, which could range from ten to seventy-five cents a shot.

In most places, the proprieties of treating the saloon girls as ladies were strictly observed, as much because Western men tended to revere all women and because the women or the saloon keeper demanded it. Any man who mistreated these women would quickly become a social outcast, and if he insulted one he would very likely be killed.

While the “proper” ladies might have scorned them, the saloon girl could count on respect from the males. And as for the “respectable women”, the saloon girls were rarely interested in the opinions of the drab, hard-working women who set themselves up to judge them. In fact, they were hard-pressed to understand why those women didn’t have enough sense to avoid working themselves to death by having babies, tending animals, and helping their husbands try to bring in a crop or tend the cattle.

In the early California Gold Rush of 1849, dance halls began to appear and spread throughout the boomtowns. While these saloons usually offered games of chance, their chief attraction was dancing. The customer generally paid 75¢ to $1.00 for a ticket to dance, with the proceeds being split between the dance hall girl and the saloon owner. After the dance, the girl would steer the gentleman to the bar, where she would make an additional commission from selling a drink.

Even today, don’t we still see the vestige remains of the Old West Saloon as the professional woman may peer down upon the bar waitress, who may peer down upon today’s prostitute? And though the gaming tables and spittoons may be long gone, the tavern or bar remains an establishment that is apparently free from the effects of the economy and will, no doubt, always remain a place where business people continue to make deals and people frequent to chase away their cares.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See:

Another fun video from our friends at Arizona Ghost Riders: Old West Saloons