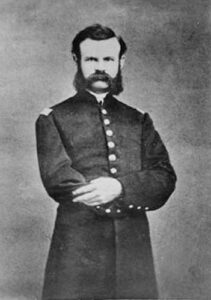

Colorado River at the Grand Canyon, Arizona, by the National Park Service.

John Wesley Powell was an American geologist, U.S. Army soldier, explorer of the American West, professor at Illinois Wesleyan University, and director of major scientific and cultural institutions. He is famous for his 1869 geographic expedition, a three-month river trip down the Green River and the upper portion of the Colorado River, including the first official U.S. government-sponsored passage through the Grand Canyon.

Powell was born in Mount Morris, New York, on March 24, 1834, the fourth child of Joseph and Mary Dean Powell. His father, a poor itinerant Methodist preacher, and his mother, a missionary, had emigrated to New York from Shrewsbury, England, in 1831. In 1838, the family moved to Jackson, Ohio, where Powell studied under George Crookham, an amateur naturalist and scholar who encouraged the young man’s interest in science, history, and literature. They moved again in 1846 to South Grove, Wisconsin, where John was responsible for the family farm while his father was away preaching. The family eventually settled in Boone County, Illinois, in 1851, and Powell became a schoolteacher there in 1852.

For brief periods throughout the 1850s when he was not teaching, Powell attended college at the Illinois Institute in Wheaton, Illinois College in Jacksonville, and Oberlin College in Ohio but did not receive a degree. Throughout the late 1850s, he undertook several self-financed expeditions along the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, collecting fossils and studying the regions’ natural history and geology.

As a young man, he undertook a series of adventures in the Mississippi River Valley. In 1855, he spent four months walking across Wisconsin. In 1856, he rowed down the Mississippi River from St. Anthony, Minnesota, to the sea. In 1857, he rowed the Ohio River from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to the Mississippi River, traveling north to reach St. Louis, Missouri. In 1858, he rowed down the Illinois River, then up the Mississippi and the Des Moines Rivers to central Iowa. In 1859, at age 25, he was elected to the Illinois Natural History Society.

Powell studied at Illinois College, Illinois Institute (later Wheaton College), and Oberlin College for over seven years while teaching but never attained a degree. During his studies, Powell acquired a knowledge of Ancient Greek and Latin. He had a restless nature and a deep interest in the natural sciences. This desire to learn about natural sciences was against his father’s wishes, yet Powell was still determined to do so. In 1861, when Powell was on a lecture tour, he decided that a civil war was inevitable; he studied military science and engineering to prepare himself for the imminent conflict.

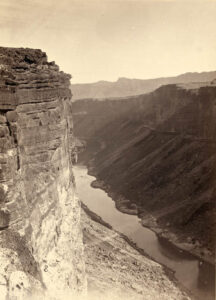

When the Civil War began, Powell’s loyalties remained with the Union and the cause of abolishing slavery. On May 8, 1861, he enlisted at Hennepin, Illinois, as a private in the 20th Illinois Infantry. He was elected sergeant-major of the regiment, and when the 20th Illinois was mustered into the Federal service a month later, he was commissioned a second lieutenant. He enlisted in the Union Army as a cartographer, typographer, and military engineer.

While stationed at Cape Girardeau, Missouri, he recruited an artillery company that became Battery F of the 2nd Illinois Light Artillery, with Powell as captain. On November 28, 1861, he took a brief leave to marry Emma Dean.

On April 6, 1862, at the Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee, he lost most of his right arm when struck by a hollow-based bullet while giving the order to fire. Field surgeons amputated the shattered part of the limb two days later. Powell convalesced and served as a recruiting officer in Illinois for the next year while living at home with his new wife. The raw nerve endings in his arm caused him pain for the rest of his life.

Despite losing an arm, Powell returned to active service in February 1863 and was later promoted to major. For the remainder of the war, while participating in actions such as the Siege of Vicksburg, the Atlanta Campaign, and the Battle of Nashville, he commanded artillery batteries under General William Tecumseh Sherman and General George Henry Thomas and served on Thomas’s staff. At the war’s end, he was made a brevet lieutenant colonel but preferred to use the title of “major.”

After leaving the Army, Powell became a professor of natural sciences at Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington. In 1866, he took a teaching post at Illinois State Normal University in Normal and became curator of the Illinois Natural History Society Museum in 1867. He declined a permanent appointment in favor of exploring the American West.

He then led a series of expeditions into the Rocky Mountains and around the Green and Colorado Rivers. One of these expeditions was with his students and wife to collect Colorado specimens and explore the Rocky Mountains Front Range. Powell, William Byers, and five others were the first white men to climb Longs Peak in 1868.

In 1868, Powell organized another expedition to explore the Colorado River from one of its tributaries in the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming southward to its union with the Gulf of California in Mexico. Powell’s ten-man party included hunters, guides, trappers, adventurers, and fellow Civil War veterans. Powell was the only scientist in the group.

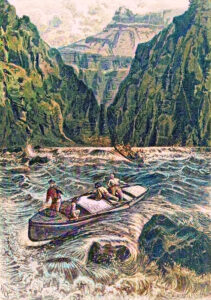

They left Green River Station, Wyoming, on May 24, 1869, in four small boats with food for ten months. Passing through dangerous rapids, the group passed down the Green River to its confluence with the Colorado River near present-day Moab, Utah, and completed the journey on August 30, 1869.

The expedition’s route traveled through the Utah canyons of the Colorado River, which Powell described in his published diary as having “wonderful features, including carved walls, royal arches, glens, alcove gulches, mounds, and monuments.” This was Glen Canyon in present-day Utah and Arizona.

After the first month, one of the boats sank in a rapid at Lodore Canyon, Utah, taking with it scientific instruments and about one-fourth of the party’s provisions. The party recovered some of the barometers used to measure cliff elevation. However, Frank Goodman, an Englishman and adventurer, was in the capsized boat after losing his personal belongings and nearly drowned. He left the expedition on July 6, 1869, near Echo Park, Colorado. He would go on to live with the Paiute Indians and later settle in Utah, where he married and had children.

The party entered the Grand Canyon on August 5, at a point that Powell named four days later, writing:

“The walls of the cañon, 2,500 feet high, are of marble of many beautiful colors, often polished below by the waves… As this great bed forms a distinctive feature of the cañon, we call it Marble Cañon.”

Powell named many other features of the Grand Canyon during the voyage, including Silver Creek, which he later renamed Bright Angel Creek.

After three summer months exploring the Colorado River’s upper canyons, the expedition passed the Paria River on August 4. They were hungry, with only musty apples, spoiled bacon, wet flour, and coffee remaining, and both physically and mentally tired as they entered the last and greatest of the canyons.

Once within the Grand Canyon, the party experienced more calamities, including losing much of its remaining food through spoilage and the near-sinking of a second boat, which was later abandoned. The scientific expedition had turned into a fight for their very survival. Powell noted in his journal that his men’s morale was dangerously low.

In the third month, Oramel G. Howland, his brother Seneca Howland, and William Dunn decided to leave the expedition on August 28, not knowing only two days remained on the trip through the Grand Canyon.

Oramel and Seneca Howland had been among the last men to sign up with Powell for the expedition. Oramel Howland had met Powell through a friend at the Rocky Mountain News, where Oramel had been a printer and editor and was the vice president of Denver, Colorado’s typographers’ union. Oramel was also a hunter. Seneca Howland, a former soldiers who had been wounded in the Battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, during the Civil War, presumably signed up at his older brother’s urging. After the war, he joined his brother, who had been in Denver since at least 1860. The brothers had been in the same boat as Frank Goodman, which had capsized just two weeks into their trip, nearly drowning them all. William H. Dunn was a hunter and trapper who met Powell in Denver in the summer of 1868.

The night before they deserted, the outfit pulled into a camp at the head of one of the worst rapids they had encountered. The Howland brothers and William Dunn believed that Powell’s plan to float the brutal rapids was suicidal.

Powell agreed, writing, “The billows are huge, and I fear our boats could not ride them… There is discontent in the camp tonight, and I fear some of the party will take to the mountains but hope not.”

The trauma of the previous three months and the imminent threat of the next morning’s rapid finally drove the three men to the end of their tolerance. Convinced they would have a better chance of surviving the desert than the raging rapids ahead, they left the expedition the next morning, hiking up what came to be known as “Separation Canyon” to the plateau above. They planned on traveling to the nearest American settlement, some 75 miles away.

In the meantime, the remaining party members steeled themselves, climbed into boats, and pushed off into the wild rapids. Two days later, on August 30, after traversing almost 930 miles, the group reached the mouth of the Virgin River.

Several weeks later, on September 15, when they reached the nearest settlement, Powell learned that the three men who left had not arrived. Though it is unknown what happened to them, they were thought to have encountered a war party of a Shivwit band of Paiute people who believed they were encroaching on their territory. The three men were killed, and their bodies were never found.

Ironically, the three murders were initially seen as more newsworthy than Powell’s successful expedition, gaining valuable publicity.

The next day, Powell halted the expedition at the confluence of the Virgin and Colorado Rivers, a site now covered by present-day Lake Mead in Nevada. Only six of the original ten men who started the expedition at Green River completed it. In addition to Powell, these included John Colton “Jack” Sumner, a hunter, trapper, and soldier in the Civil War; John’s brother Walter H. Powell, a captain in the Civil War; George Y. Bradley, a lieutenant in the Civil War and the expedition’s chronicler; W.R. Hawkins, a cook and soldier in the Civil War; and Andrew Hall, a Scotsman, and the youngest of the expedition.

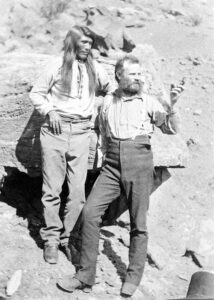

In planning his next expedition, retracing part of the route of 1869, he employed the services of Jacob Hamblin, a Mormon missionary in southern Utah who had cultivated relationships with Native Americans. Before setting out, Powell used Hamblin as a negotiator to ensure the safety of his expedition from local Indian groups.

When Powell embarked on his second trip through the Grand Canyon in 1871, the publicity from the first trip ensured that the second voyage was far better financed than the first. Backed by an appropriation from the U.S. Congress, this expedition had an 11-man crew that included several trained scientists and three photographers. The second voyage, which lasted from May 22, 1871, to September 7, 1872, produced the first reliable maps of the Colorado River, multiple photographs, and various papers. His maps included the ominous depths of the Grand Canyon in Arizona, which Powell called “The Great Unknown.” He and his crew were the first known people of European descent to make this journey by river and document the details of the route, detailing the changing landscapes and the people, plants, and animals they encountered.

Powell’s successful journey opened a vast area of the West to exploration and settlement. Many other explorers and river runners followed in his footsteps, leaving their marks on the area’s history. He also foresaw the difficulty of settling in the west, saying the land was primarily unsuitable for agricultural development, except for through careful use of scant water sources.

Powell recounted the events of both expeditions in his book Exploration of the Colorado River of the West and Its Tributaries. Powell’s book and official reports contained much information on the Native Americans of the southern Rocky Mountains and Colorado Plateau regions.

In 1877, he published Introduction to the Study of Indian Languages, with Words, Phrases, and Sentences to Be Collected.

In recognition of his contribution, Powell was appointed the first director of the U.S. Bureau of Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution in 1879. Powell held the post until his death.

Powell also served as director of the U.S. Geological Survey from 1881 to 1894. During his tenure, he touched off controversy by advocating strict conservation of water resources in the developing states and territories of the arid West.

“There is not enough water to irrigate all the lands… I tell you, gentlemen, you are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights, for there is not enough water to supply the land.”

— John Wesley Powell, remarking at a Los Angeles congress of farmers and developers in October 1893.

Subsequent interstate conflicts over the water of the Colorado and other Western rivers proved Powell’s words to be prophetic.

Powell died on September 23, 1902, at his family’s vacation cottage in Haven, Maine. He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia.

Powell Plateau, a butte in Grand Canyon National Park, is named in his honor, as is Lake Powell, the vast lake that formed on the Colorado River behind Glen Canyon Dam after its completion in 1963. Powell Mountain, in Kings Canyon National Park, California, also bears the explorer’s name.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

Also See:

Harvey Hotels & Restaurants Along the Rails

National Parks, Monuments & Historic Sites

Sources:

Arizona State University

Encyclopedia Britannica

History Channel

National Park Service – Culture-Explorers

National Park Service – Geology

National Park Service – History & Culture

VTDigger

U.S. Geological Survey

Wikipedia