Located just south of the mid-point of South Carolina’s coastline, at the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper Rivers, the historic city of Charleston is the oldest city in the state. Founded in 1670 and first called Charles Towne, it was named for King Charles II. Charleston’s rich history includes periods of great wealth and prosperity followed by generations of great poverty; two major wars being fought within its boundaries, followed by the occupation of invading armies; numerous skirmishes with pirates and Indians; catastrophic fires that obliterated entire blocks of the city, several hurricanes; and the largest earthquake ever to rock the eastern coast of the United States. These events of the last three centuries have all combined to make Charleston an unrivaled tourist destination for history buffs.

In 1663, King Charles II granted a charter for Carolina territory to eight of his loyal friends, but it would be seven years before the first settlement was established. Charles Town was established as Carolina’s capital city on the west bank of the Ashley River. Two years later, Charles Town had about 30 buildings and 200-300 settlers. In 1680, the town moved to its present location on the main peninsula and, in 1783, adopted its present name.

The settlement was often subject to attack from sea and land by Spain, France, and pirates, and resistance from Native Americans. While the earliest settlers primarily came from England, they were followed by other immigrants, including French, Scottish, Irish, Germans, and others. These various ethnic groups brought numerous Protestant denominations, Roman Catholicism, and Judaism, which would later earn Charleston the nickname of the “Holy City” for its long tolerance for religions of all types and its many historic churches.

The deerskin trade was the primary business in Charleston during its early years, as alliances with the Cherokee and Creek ensured a steady supply of deer hides. Between 1699 and 1715, an average of 54,000 deerskins were exported annually to Europe, which were used to produce men’s fashionable and practical buckskin pantaloons, gloves, and book bindings. The deerskin market would continue to grow through the mid-18th century.

Colonial landowners experimented with various crops, including tea, silk, rice, and indigo, which would become a leading export by 1750. By this time, Charleston had become a bustling trade center and the wealthiest and largest city south of Philadelphia.

By 1770 it was the fourth-largest port in the colonies, after only Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, and boasted a population of 11,000. Several cultural and social organizations were established as the city prospered, including the first theater in America in 1736, numerous benevolent societies, and the Charleston Library Society in 1748. This group would also help establish the College of Charleston in 1770, the oldest in the state.

When the American Revolution began, Charleston would find itself and its port a target – twice being attacked by the British.

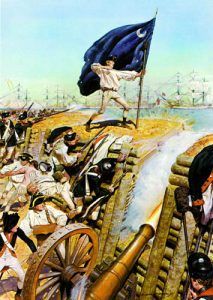

On June 28, 1776, British General Henry Clinton, with 2,000 men and a naval squadron, tried to seize Charleston, hoping for a simultaneous Loyalist uprising in South Carolina. However, their mission failed when explosives failed to penetrate Fort Moultrie’s unfinished yet thick palmetto log walls, and no local Loyalists attacked the town from within as the British had hoped.

However, General Clinton would return before the war’s end in April 1780 and attack again, this time with greater success. Marching on Charleston with 14,000 soldiers, Clinton cut off the city from relief and began the siege on April 1.

Several skirmishes took place for the next six weeks until Continental Army Major General Benjamin Lincoln was forced to surrender on May 12. The city’s loss and its surrender of 5,000 troops to the British was the most significant loss suffered by the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War. The British retained control of the city until December 1782, after which the city officially changed its name to Charleston.

Charleston lost its status as the capital in 1786 to Columbia due to its central location in the state. However, the city became even more prosperous with large plantations. In 1790, Charleston was called home to more than 16,000 people and was the fifth-largest city in North America. In 1783, the invention of the cotton gin revolutionized cotton production and quickly became South Carolina’s major export. The cotton industry and the majority of the workforce in the city relied heavily on slave labor. By 1820, Charleston’s population had grown to 23,000, and African-Americans were the majority.

In 1822, a free African-American man named Denmark Vesey planned a slave revolt that called for free blacks to assist hundreds of slaves in killing their owners and temporarily seizing the city of Charleston before sailing away to Haiti. However, the plot was leaked, and hundreds of blacks were arrested in the conspiracy. In total, 67 men were convicted and 35 hanged, including Denmark Vesey. Increased restrictions were afterward placed on slaves and free blacks, including a law that all black seaman be kept at the jail while in port.

On December 20, 1860, following the election of Abraham Lincoln, South Carolina Legislators voted to secede from the Union, and Charleston became a hotbed of skirmishes and battles during the Civil War. Citadel cadets fired the first shots of the war from Morris Island in Charleston’s Harbor on January 9, 1861, at the Union ship Star of the West, which was entering the harbor.

On April 12, 1861, General Pierre G. T. Beauregard opened fire on the Union-held Fort Sumter in the harbor. After a 34-hour bombardment, Major Robert Anderson surrendered the fort, thus starting the war and triggering a massive call for Federal troops to put down the rebellion.

Throughout the Civil War, Charleston and its surrounding fortifications were repeatedly targeted by the Union Army and Navy, causing considerable damage and keeping up a blockade that shut down most commercial traffic. However, the city did not fall to Federal forces until the last months of the war. By that time, the Union attacks had worn down the city’s defenders, and in February 1865, General William T. Sherman began his march through South Carolina.

On February 15, General Pierre Beauregard ordered the evacuation of remaining Confederate forces, and three days later, Charleston’s mayor surrendered the city to Union General Alexander Schimmelfennig.

Federal troops then moved into the city, taking control of many sites, including the United States Arsenal and the Citadel Military Academy, which the Confederate army had seized at the outbreak of the war. Afterward, Federal forces remained in Charleston during the city’s reconstruction.

With the war finally over, Charleston, like many Southern cities, were devastated. One journalist in September 1865 described it as: “a city of ruins, of desolation, of vacant houses, of widowed women, of rotten wharves, of deserted warehouses, of weed-wild gardens, of miles of grass-grown streets, of acres of pitiful and voiceful barrenness.”

With the city in ruins and the freed slaves facing poverty and discrimination, Charleston’s prosperity ended. But, the city would rebuild again, and many of its citizens returned as industries were revived. As the city’s economy improved, it worked to restore and rebuild several organizations. In 1865 the Avery Normal Institute was established as a free private school for Charleston’s African American population. Today, the building remains part of the College of Charleston and operates as the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture.

General William T. Sherman lent his support to convert the United States Arsenal into the Porter Military Academy, an educational facility for former soldiers and boys left orphaned or destitute by the war. The Academy later joined with Gaud School and continues to operate as a prep school called the Porter-Gaud School.

The elaborate Renaissance Revival style United States Post Office and Courthouse was completed in 1886 and signaled renewed life in the heart of the city. Today, it still functions as it did initially, used as the downtown branch of the post office and federal district court.

The same year the courthouse building was completed, Charleston suffered another tragedy when an earthquake nearly destroyed it on August 31, 1886. Measuring 7.5 on the Richter scale, it was the most damaging earthquake to hit the Southeastern United States. Felt as far away as Boston, Chicago, and New Orleans, it damaged 2,000 buildings in Charleston and caused $6 million worth of damage. Again Charleston rebuilt.

Charleston’s economy declined after the Civil War but would grow slowly but steadily in the 20th century. Maintaining a large military presence that supported the local economy was boosted by building a naval shipyard in WWI and with the many industries established during WWII.

Like other cities across the United States, it went through its own Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and ’60s, one of the last major events of which was the Hospital Strike of 1969. After Medical College Hospital fired 12 employees for trying to organize a union in the hospital, over 60 other employees walked out. They began a strike that lasted through the summer and brought major Civil Rights leaders to the city.

It was not until the election of Joseph P. Riley, Jr. as mayor in 1975 that the city experienced a modern-day renaissance. Under his leadership, Charleston increased its commitment to racial harmony and progress, achieved a substantial decrease in crime, and experienced a remarkable revitalization of its historic downtown business district. He has also been the major proponent of reviving Charleston’s economic and cultural heritage.

Though the city has experienced war, fires, and hurricanes, an extraordinary number of Charleston’s historic buildings remain. The city’s historic district looks much as it has throughout the centuries, boasting 73 pre-Revolutionary buildings, 136 late 18th century structures, and over 600 others built in the 1840s, making it one of the most complete historic districts in the country. In total, the city sports more than 1,400 historically significant buildings.

Today, Charleston manufactures many products, including paper and cigars, and its port is one of the leading sources of revenue, but the city thrives primarily on tourism. The County Seat of Charleston County, the city is called home to about 150,000 people today.

Numerous tours, museums, two forts, galleries, theaters, and musical venues are available for entertainment. The downtown Charleston Historic District is best experienced on foot to see the many buildings and historical sites such as the Market Hall and Sheds, the U.S. Customs House, the Old Jail, Marine Hospital, Dock Street Theatre, and more. Charleston’s nickname, “the Holy City,” speaks to the many religious sites that serve its neighborhoods, some of which are more than 250 years old.

More Information:

Charleston Area Convention and Visitor Bureau

423 King Street

Charleston, South Carolina 29403

843-853-8000

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See:

Fort Moultrie – Tracing our Coastal Defenses

Fort Sumter – Beginning the Civil War

Lavinia Fisher – First American Female Serial Killer

South Carolina – The Palmetto State

Sources: