By Eli Greenawalt Foster, 1899

Slavery and States’ Rights were the two causes of the Civil War in the United States. They came before the people in various forms, which, despite repeated compromises, only widened the sentiments between the North and South. The Missouri Compromise was the first of a series of enactments and struggles between the two sections on slavery. The election of Abraham Lincoln on a platform opposed to the extension of slavery was the last of the series, which grew more bitter and antagonistic until it culminated in the firing upon Fort Sumter, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861.

The Nullification Act of South Carolina, in 1832, was the first serious manifestation of the doctrine of States’ Rights, which finally ended in the secession ordinances of the Southern States and precipitated the great American conflict.

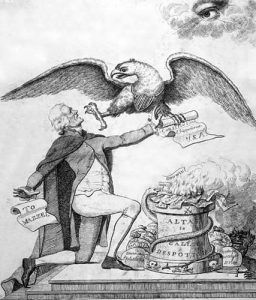

State Rights

Politicians held different views from the beginning of our national history regarding the nature of the bond that held the States together. One class of statesmen maintained that the Union was a league or confederation which might be dissolved at the will of any of the States. Under this theory, a failure by the general government to protect the rights, expressed or assumed, of any of the States entirely released these States from obligations to the Union and restored them to their former position of separate sovereign States.

Another class of statesmen held that the Federal Union constituted a nation with a strong central government and that no State could secede from the Union without the consent of all the others. These were the different constructions placed upon the U.S. Constitution, from which no severe conflict arose until specific material questions came before the people for a solution. Chief among these were those related to tariffs and slavery. The South, engaged entirely in agricultural industries, demanded free trade. The North derived much of its wealth from manufacturing industries and called for protection. When the Tariff Act of 1832 became a law, it caused intense opposition among the people of the South. It led South Carolina to declare the act null and void and threaten to secede from the Union if the Federal Government should endeavor to enforce the law. The prompt and vigorous action of President Andrew Jackson in sending troops to the rebellious state restored order, and Henry Clay’s Compromise of 1850 pacified the leaders for a time. They, however, did not abandon the principle of secession but only shifted it from the tariff issue, in which they had scored a victory, to the much compromised and yet uncompromising issue of slavery extension.

Differences Between the North and South

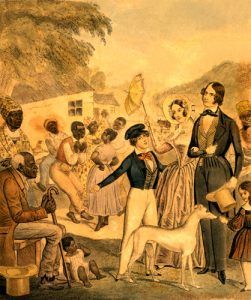

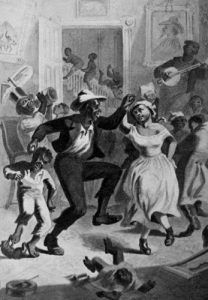

People who settled these two sections differed in thought, habit, and customs. They sprung from different classes, though most all were of English origin. The North was settled by the Puritans, who fled from England’s oppression and religious persecution in search of freedom and a purer system of faith and worship. The early settlers of the South were the Cavaliers, who were loyal to the State and their king’s religion. The Puritans belonged to the middle class — laborers and minor landowners and came to establish homes for themselves. The Cavaliers belonged mainly to the aristocracy and nobility and came searching for wealth. The representatives of these two classes of society impressed upon the respective sections’ development. They settled and molded the customs and institutions for a more varied class of settlers who followed them. The character of the settlers in the North and the nature of the soil and climate tended toward the cultivation of small estates. However, the early settlers of the South brought with them from England the idea of large estates, which climate and the introduction of African slavery aided in perpetuating. The North was strongly imbued with the love of liberty and a desire for equal opportunities. Free schools were established, manufacturing sprung up, and cities multiplied.

On the other hand, the South became agricultural, and educational advantages were confined to the wealthy. This contrast in the people’s character, the difference in the industries of the two sections, and the different climate and soil conditions made slave labor more profitable in the South than in the North. They showed how easily one section could become a slaveholding state and another a free state.

Growth Of Slavery

Slavery was introduced in the colonies in 1619 at Jamestown, Virginia. The importation of slaves continued, and at the close of the American Revolution, the slaves in the States numbered about 600,000. At the same time, only an estimated 50,000 free persons of color were distributed through the colonies. In her greed for gain, Europe had woven slavery into her colonial policy that her home revenues might be greater. No colony was without slaves, though they were more common in the South than in the North. In vain had the Virginia House of Burgesses protested against the “inhumanity of the slave trade.” The colony of South Carolina passed an act in 1760 prohibiting the importation of slaves, but the British government refused to sanction it. Other colonies also endeavored to restrict the trade but without success.

The invention of the cotton-gin by Eli Whitney in 1793 greatly stimulated the demand for blacks and increased the importation of slaves. Before the cotton gin’s invention, separating the seed from the cotton was slow, tedious, and expensive.

Using this machine, one person could accomplish the work of several hundred hands. Cotton cultivation was greatly extended, which made a demand for slave labor in the South, where cotton was grown and increased the value of slaves. The number of slaves increased rapidly even though restrictions were placed upon slave traffic, and foreign importation was prohibited by law in 1808. When the Civil War began, the number of slaves in the United States was about 4,000,000. Southern opinion, which in the early colonial days considered slavery evil, gradually changed. Many had come to regard it as a great moral, social, and political good, — an institution ordained by Providence for civilizing and educating the black race.

Movements Toward Freedom Of The Slaves

At the opening of the Civil War, there were more slaves in the United States than in all other countries combined. These were all confined to the States south of Pennsylvania and the Ohio River. All the Northern States had freed their slaves before or soon after adopting the U.S. Constitution. Vermont took the lead in 1777; Pennsylvania followed in 1780; eventually, all other Northern States followed in abolishing slavery or providing measures to effect its gradual abolition. The last to abolish it was New Jersey in 1804.

Though America is the “land of the free,” slavery clung to its soil with greater tenacity than it did to European countries. Great Britain gave freedom to the slaves in her colonies in 1838. The French government decreed the immediate emancipation of the colonies’ slaves in 1848. Other European powers followed Great Britain’s example. Many South American republics—Mexico, as early as 1829 — provided for the abolition of slavery.

George Washington, in his will, provided for the emancipation of his own slaves. John Adams believed that slavery should be abolished in the United States. Thomas Jefferson, himself a slaveholder, declared, when speaking of this institution, “I tremble for my country when I remember that God is just.” Patrick Henry, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison opposed the principle of slavery.

Most of the wisest and best men of the time, both North and South, looked forward with confidence and hope to the speedy abolition of an institution so opposed to the principles of Christianity and so dangerous to the interests of society and the state.

In 1787, the country, including Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, was organized into the Northwest Territory. Freedom was guaranteed to this region by the insertion of this famous clause: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall exist in this Territory, otherwise than in punishment of crimes.” This anti-slavery clause was submitted three years before by Thomas Jefferson for the government of the Northwest Territory and that south of the Ohio River. The slavery provision was rejected for the territory south of the Ohio River, and later, four slave States — Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi — were formed out of it. In contrast, the territory to the north of the Ohio River was permanently attached to the principles of freedom.

In 1803, the boundaries of the United States were extended to include that vast region west of the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains, known as the Louisiana Territory. Of the various states formed out of this region afterward, Missouri was the first to apply for admission to the Union. The main question concerning the admission of this state was whether it should be free or slave.

The Missouri Compromise prohibited slavery in the unorganized territory of the Great Plains (dark green) and permitted it in Missouri (yellow) and the Arkansas Territory (lower blue area).

Before abolishing slavery in the North and the admission of the free States north of the Ohio River, slavery had not become a sectional affair. Many in the South during the Revolutionary period believed in the gradual emancipation of the slaves. But, sentiment had changed; their chief concern became the perpetuation of the institution. Sectional lines were drawn on slavery as an issue. A new epoch in slavery was instituted when Missouri applied for admission to the Union as a State in 1819. The South endeavored to extend slavery to new territory, while the North opposed it. The discussion was long and acrimonious. It was the real beginning of the great political struggle, out of which came the Civil War.

The famous Missouri Compromise provided:

- That Missouri should be admitted to the Union as a slave State.

- That slavery or involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime, should be prohibited in the remaining part of the Louisiana Purchase, lying north of latitude 36 degrees 30 minutes, which formed the southern boundary of Missouri.

- No provision was made relative to the admission of the Territories south of this line, but, as slavery already existed there, they were tacitly surrendered to the slave power.

Maine was admitted as a free State on the principle that one free and one slave State should be admitted simultaneously. The compromise from which so much was expected settled nothing. The Southern people continued to feel and act as if they had been hindered in exercising their rights.

Mexico declared itself independent of Spain in 1821 and established a republic. In 1829, the President of Mexico proclaimed the abolition of slavery within the limits of his territory, but Texas refused to comply. The slave power of the United States sent money, supplies, and arms to Texas and aided in stirring up a revolution with the express purpose of annexing more slave States to the Union. Sam Houston, former Governor of Tennessee, headed the revolution, and in 1836, Texas became a Republic independent of Mexico.

The next year, she applied for admission to the Union. Still, opposition in the House and Senate, exposing the duplicity with which the Jackson administration had acted toward Mexico, for the time silenced the agitators for annexation. It was not long, however, until another effort was made to extend the slave territory. A joint resolution annexing Texas received the President’s signature on March 1, 1845. It also pledged the faith of the United States to permit new States to be formed of this territory, not exceeding four. Texas thus became a full-fledged State in the Union, and President James Polk sent troops to occupy the territory between the Nueces and the Rio Grande, which Mexico claimed as her soil. In the war that followed, the territory now comprising the States and Territories of California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming was ceded to the United States.

The Compromise Of 1850 (the Omnibus Bill)

In 1850, California applied for admission to the Union as a free State, which created a stir among the slaveholding States. The angry menace to harmony and unity again appeared. The primary objective in annexing Texas and conducting the Mexican-American War was acquiring slave territory. After a bitter discussion, the Wilmot Proviso, excluding slavery from all territory acquired due to the war, was voted down. With the admission of Arkansas in 1836 as a slave State came the admission of Michigan as a free State. With the admission of Iowa as a free State, the balance of slavery was maintained by providing in the same bill for the admission of Florida as a slave State. However, its population was not near the number required for the admission of States. The admission of free Wisconsin balanced that of a slave.

The admission of California as a free State would disturb the equilibrium between the free and slave States, give the North the most substantial benefits of the Mexican-American War, and defeat the objective for which it had been waged. A tremendous political struggle ensued. Threats of secession were rife. Fiery and passionate eloquence filled the air, in the midst of which Henry Clay came forward with his compromise bill.

The bill was stripped of provision after provision until, when passed, it provided for the territorial government of Utah and nothing more. The rejected provisions were afterward taken up one by one as a special order of business and passed with little change from the original bill. The Omnibus Bill was recreated, containing the following provisions:

- California should be admitted as a free State.

- New states not exceeding four might be formed out of Texas. The people of each state were to decide whether the state should be free or slave.

- Texas should be paid $10,000,000 for her claim on New Mexico.

- Utah and New Mexico should be organized as territories without mention of slavery.

- Slave trade should be prohibited in the District of Columbia.

- Slaves escaping from their masters into free States should be arrested and returned to them.

The last clause is called the “Fugitive Slave Law,” the passage of which caused intense opposition in the North. Personal liberty laws were passed by the Northern States, prohibiting state officers from aiding in the arrest and return of any slave. Counsel was provided for the arrested blacks, and the practical operation of the fugitive slave act was annulled.

The passage of the Omnibus Bill was the death knell of the Whig Party, and instead of pacifying the feelings of the contending elements, it contained the seeds for new and greater conflicts in its provisions.

The Kansas-Nebraska Bill, 1854

In 1854, Stephen A. Douglas introduced a bill to organize two Territories, Kansas and Nebraska. The people of these Territories were to decide whether the States should come into the Union free or slave. It virtually repealed the Missouri Compromise, which guaranteed freedom to this section, and a territory nearly as large as the 13 original States was opened to slavery. Of the two territories, Kansas was the more southerly and, therefore, the more favorably situated for planting the institution of slavery.

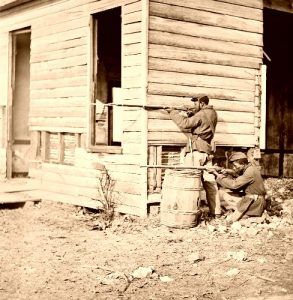

Kansas thus became the battleground for the contending elements of freedom and slavery. Great preparations were made both North and South for the state’s settlement. Pro-slavery societies, known as Blue Lodges and Social Bands, were formed in the South. Pro-slavery immigrants poured into the new Territory from Missouri. Eli Thayer of Worcester, Massachusetts, formed the Emigrant Aid Society. Utilizing it and similar societies, a stream of anti-slavery emigrants was sent to Kansas. At the elections, many Missourians crossed the border, intimidated election officers, and cast thousands of illegal votes for the pro-slavery candidates, who thus received a large majority of all votes. The anti-slavery settlers, who had cast most of the legal votes, repudiated the election and chose their own officers.

With two rival Legislatures and the opposing parties of freedom and slavery bitterly contending for supremacy, matters soon drifted into the Civil War in the new Territory. The burning of houses, sacking of towns, and the taking of life continued for several years. This bloody drama awakened many persons’ consciences to the slave power’s real intent and purposes. Although the pro-slavery party had the moral and material support of the President and cabinet, Kansas was finally won to the cause of freedom. It was admitted to the Union in 1861.

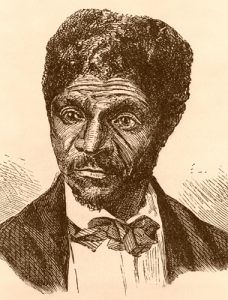

Dred Scott Decision, 1857

Dred Scott was a slave taken by his master, Dr. Emerson, from the State of Missouri to the free State of Illinois, then to Fort Snelling, near St. Paul, Minnesota. He married with his master’s consent and was taken back to Missouri in 1838, where he was sold to John P.A. Sanford with his wife and children. Dred Scott sued for the liberty of himself and his family, alleging that his residence in a free State and in a Territory from which the Missouri Compromise excluded slavery established his freedom. An action for trespass, brought in a St. Louis, Missouri court, was decided in Scott’s favor, which the Missouri Supreme Court reversed. The case was then taken to the Federal court. The case ceased to be of personal interest only and assumed national importance as a contest for constitutional principles between the slavery and anti-slavery parties. Both the Circuit and the Supreme Court of the United States decided against freedom of Scott. In the final decision, the court affirmed that “no negro, slave or free, who was of slave ancestry, was entitled to sue in the United States courts.”

After denying its own jurisdiction, the court passed upon the merits and discussed the constitutionality of the points of interest to the opposing parties. It declared the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional, that slave-owners could carry their slaves into any of the Territories, and that the people of those Territories could not lawfully hinder them; that a black person was not a citizen, and by terms of the U.S. Constitution could not become a citizen of the United States. A mandate was issued directing the suit to be dismissed for want of jurisdiction. Dred Scott soon obtained, by the grace of his master, that freedom that the courts denied him.

By this Supreme Court decision, considered the most infamous of all its decisions, slaves could be taken anywhere, and slavery made national. Instead of extending the institution, as was the judges’ intention (a majority of whom were from slave States), it united the people of the North in more determined opposition to the extension of slavery.

Anti-slavery Publications

The opinions on the slavery question separated the people of the North and South. The effort on the part of the South to extend the institution was the source of the bitterest friction between the two sections. At the time of the Missouri Compromise, a majority of the people of the North had not thought of abolishing slavery in the Southern States; in fact, this was not their intention at the beginning of the Civil War. There were some inspired souls in the North; however, they devoted their talents to the abolition of slavery at an early date. Some of the most prominent deserve mention. The press and the platform were used with great effect to arouse the public conscience to realize the great national wrong.

The Liberator, a weekly journal published by William Lloyd Garrison, then a youth of 26, appeared in Boston in 1831. His words indicated the spirit of the paper in the first issue: “I will be as harsh as truth and as uncompromising as justice. On this subject, I do not wish to speak, think, or write in moderation. No! No! I am in earnest — I will not equivocate — I will not excuse — I will not retreat a single inch — and I will be heard! ”

He was dragged through the streets of Boston with a rope around his body; he was threatened with death if he did not desist, but he continued to publish his paper and to organize abolition societies until the great wrong he assailed was eradicated.

Frederick Douglass, a runaway slave from Maryland, edited the North Star in Rochester, New York.

Reverend Elijah P. Lovejoy attempted to establish a religious and anti-slavery paper at St. Louis, Missouri, and then at Alton, Illinois, 1835-37. Three times in one year, a pro-slavery mob destroyed his press. While engaged in setting it up a fourth time, a pro-slavery mob attacked him, and he was killed.

John G. Whittier, the Quaker anti-slavery poet whose burning lyrics flew across the country and molded sentiment against slavery, narrowly escaped death at the hands of a mob at Concord, New Hampshire in 1836, while attending an anti-slavery meeting.

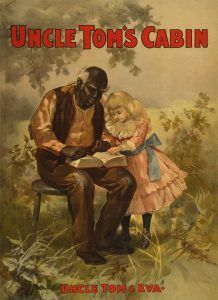

Of the literary forces that aided in directing sentiment against slavery, the weightiest was the book Uncle Tom’s Cabin, written by Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe. It first appeared as a serial in the National Era, an anti-slavery newspaper in Washington, D.C, but attracted little attention. The great bookhouses were afraid to publish it lest it should hurt their Southern trade. A new house in Boston published it in 1852. It immediately attracted great attention and became one of the most popular novels ever written. Whittier wrote to Garrison: “What a glorious work Harriet Beecher Stowe has wrought! Thanks to the Fugitive Slave Law. Better for slavery that that law had never been enacted, for it gave the occasion for Uncle Tom’s Cabin “The sale of the book was almost without limit, at home and abroad. However, its greatest success was its moral weight in unifying and antagonizing the Northern conscience to the iniquities of the slave power.

The Impending Crisis of the South argued against slavery on moral and economic grounds. Its author, Hinton Bowan Helper, was one of the South’s non-slaveholders who pleaded for his class’s rights. The book created quite a strong sensation at the time.

The constant discussion and agitation aroused fears and animosities. The mail was regularly searched in many Southern post offices, and any anti-slavery literature was burned. “Abolitionist” became the severest term of reproach in the South. The churches became violently agitated over the burning issue. Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian denominations separated, North and South, on the subject of slavery.

From the influence of platform, pulpit, society, and press arrayed against the encroaching steps of slavery upon the territory formally dedicated to freedom, a crystallized sentiment emerged, expressed in the principles of the Republican Party in its platform of 1856.

Anti-slavery Parties

In 1840, the “Liberty Party” put a national ticket in the field. James G. Birney was nominated but received only a small vote. Four years later, he received more than 62,000 votes on the same ticket.

The party favored abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia and all national territories. It also favored repealing the Fugitive Slave Law, prohibiting slavery in new Territories and new States, as opposed to the internal slave trade, and opposing the annexation of Texas. In 1848, its adherents joined fortunes with the Free-Soil Party.

The “Free-Soil Party” was organized by bolting Whigs and Democrats, who held advanced views on the slavery question. The followers of the old Liberty Party joined it. Its leaders were Charles Francis Adams, Salmon P. Chase, Charles Sumner, William H. Seward, John P. Hale, John A. Dix, and Henry Wilson.

The Presidential candidates in 1848 and 1852 received a considerable popular vote but were insufficient to carry the electors in any State. It advocated non-interference with slavery where it already existed but opposed all compromises with slavery, the formation of any more slave territory, or the admission of any slave State.

The Republican Party – The constant and resolute aggressions of the slave power called forth an equally aggressive free-soil movement in the North. Whigs, Wilmot-Proviso Democrats, and the Free Soilers united to form a new party to prevent the spread of slavery into new territory. The various elements opposed to slavery were thus skillfully and smoothly kneaded into the new Republican Party. John C. Fremont was the first candidate for President. He received 114 electoral votes; James Buchanan, 174; and Millard Fillmore, 8. This formidable vote might well have carried dismay into the pro-slavery columns. The election of Buchanan on a pro-slavery platform gave the South little ground for complaint, but, as events have shown, it allowed them to prepare for war. Through the “treachery of the Secretary of War, John B. Floyd, and the administration’s indifference at Washington, large amounts of arms, ammunition, and stores were transferred to the South.

When the time came to choose a President, the people were divided into four parties. The Republicans nominated Abraham Lincoln on the platform that there was no law for slavery in Territories, no power to enact one, and that Congress was bound to prohibit it or exclude it from all Federal territories. The Southern Democracy nominated John C. Breckinridge on a platform distinctly favoring the extension of slavery. The Northern Democracy nominated Stephen A. Douglas on a platform that would free the people to decide the slavery question for themselves in each Territory.

The Constitutional Union Party nominated John Bell of Tennessee on this platform: “The Constitution of the country, the Union of the States, and the enforcement of the laws.” The popular vote decided against the extension of slavery. Lincoln received 180 votes in the electoral college, Breckinridge 72, Bell 39, and Douglas 12.

The slavery question was the issue in the campaign.

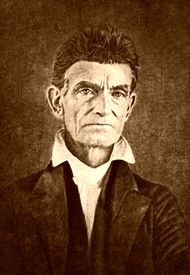

John Brown’s Raid, 1859

John Brown was an abolitionist. He moved to Kansas in 1855, in time to become a conspicuous figure in the thrilling scenes of that State. Five of his sons had settled near Osawatomie the year before, and all took up the cause of freedom. Slavery would undoubtedly have triumphed over legal and legislative skill had not the sword been thrown into the balance by such bold and resolute men as Brown.

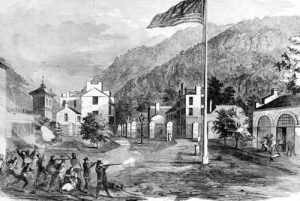

After peace had been restored in Kansas, he conceived the idea of freeing the slaves of the South. Settling on a small farm near Harper’s Ferry, he secretly collected material for executing his designs. He, with 21 associates, appeared before Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, on October 16, 1859, easily overpowered the guards, and took possession of the armory belonging to the United States. He expected to create an uprising among the slaves, arm them with the guns stored there, and liberate the blacks of the South.

Between 40 and 50 citizens were captured and confined in the armory by him, and some slaves were liberated. The people of the town, arming themselves, attacked the insurgents. The U.S. Marine, commanded by Colonel Robert E. Lee, arrived. The militia commenced to pour in. Thirteen of Brown’s men were killed, two of whom were his sons. Two of his men escaped, and the rest were captured. Brown himself was dangerously wounded.

He was speedily tried before a Virginia court and was executed on December 2, 1859. His execution for this wild and erratic scheme reflects little credit upon the elements of humanity and generosity of the officers of Virginia when we consider that Jefferson Davis and his followers suffered no such fate for conducting the stupendous campaign of the great Rebellion.

Brown died a martyr for the cause of liberating enslaved people. His spirit was present in many battles that followed, and many regiments were stirred by the words of the popular war song: “John Brown’s body lies a-moldering in the grave, But his soul is marching on.”

Secession

As soon as it became known that Abraham Lincoln was elected, South Carolina called a convention to consider an ordinance of secession, which unanimously passed on December 20, 1860. Commissioners were sent to the other cotton States to urge them to follow the same course.

President James Buchanan encouraged the Southern cause with his vacillating action. His message to Congress in December 1860, which was strongly disunion in character, contained these words: “After much serious reflection, I have arrived at the conclusion that no power has been delegated to Congress, or to any other department of the Federal Government, to coerce a State into submission which is attempting to withdraw or has withdrawn from the Union.” He might have profited from Jackson’s vigorous measures a third of a century before when South Carolina threatened to secede.

Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina withdrew from the Union in the order named. Four slave states — Delaware, Maryland, Missouri, and Kentucky — did not secede. In these, the sentiment was divided between the North and the South, with the preponderance favoring the former.

The ordinances of secession were quickly followed by the seizure of the United States forts, arsenals, and customs houses in the seceding States and the formation of a Confederate Government. The capital was located in Montgomery, Alabama. Jefferson Davis was chosen President, and Alexander H. Stephens was Vice President. Southern officers resigned from Congress, the Cabinet, the Army, and the Navy.

The constitution of the Confederate States of America was a close pattern of that from whose banner they had withdrawn, except that it made slavery the cornerstone of the new system and forbade a protective tariff.

Crittenden Compromise, December 1860

A Senate committee, composed of men of different politics and from different sections of the country, made a last effort to patch up a scheme by which slavery and freedom might work out their ambitions together. The patriotic John J. Crittenden, a Kentucky committee member, submitted the plan. It offered guarantees against arbitrary abolition of slavery by Congress in the slave States or places once within their limits, such as forts and navy yards. It restrained Federal interference with the interstate transportation of slaves. It bound the United States to pay fugitive slaves when local violence prevented their return. It advised the Northern States to repeal their personal liberty laws. But, its main feature was to establish, by constitutional amendment, the Missouri Compromise line (36° 30′), running east and west across the continent, as a permanent barrier between the free and slave States. All efforts to reconcile the conflicting opinions proved futile. The vital points were rejected by members from the North and South alike.

Inauguration Of Lincoln, March 4, 1861

Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated on March 4, 1861. From his home in Springfield, Illinois, to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, he was everywhere received with demonstrations of loyalty. He delivered addresses to the people of the capitals and other large cities of the States through which he passed. Baltimore was a slaveholding city but was infested with many people who were loud and fierce in denouncing Lincoln and the principles he represented. Frequent reports were heard that a plan had been concocted for the assassination of the new President as he passed through the city. His friends persuaded him to go to Washington on a special train before the one on which his passage had been announced.

Lincoln’s inaugural address was an able state paper. It was an admirable effort to calm the ardor of the South for disunion without compromising any of the principles of the party that had elected him. The following detached sentences will express Lincoln’s views on some of the leading issues of that hour:

“I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in any of the States where it exists.”

“The power confided in me will be used to hold, occupy, and possess the property and places belonging to the Government.”

“I shall take care, as the Constitution expressly enjoins upon me, that the laws of the Union be faithfully executed in all States.”

“No State, upon its own mere motion, can lawfully get out of the Union.”

“In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of Civil War. The Government will not assail you.”

The conspirators accepted the olive branch of peace as a challenge to war.

By Eli Greenawalt Foster, 1899. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

Also See:

African-Americans – From Slavery to Equality

Chronology of Slavery in the United States

Slavery – Cause and Catalyst of the Civil War

Civil War Photo Print Galleries

About the Author: “Causes of the Civil War” is a chapter from the book “The Civil War by Campaigns” written by Eli Greenawalt Foster, 1899, by Crane Publishing.