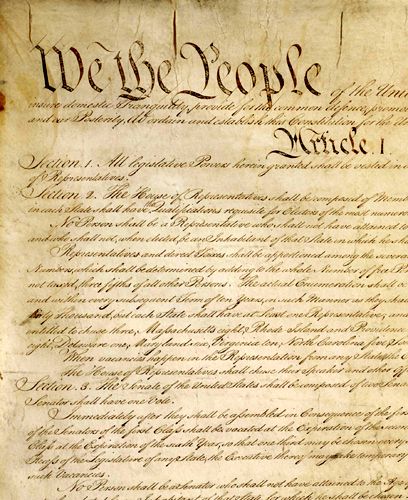

We, the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, ensure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

— Preamble to the Constitution

The Constitution of the United States of America is the supreme law of the nation. Empowered with the sovereign authority of the people by the framers and the consent of the legislatures of the states, it is the source of all government powers, and also provides essential limitations on the government that protect the fundamental rights of United States citizens.

Why a Constitution?

The need for the Constitution grew from problems with the Articles of Confederation, which established a “firm league of friendship” between the states and vested most power in a Congress of the Confederation. This power was, however, extremely limited — the central government conducted diplomacy and made war, set weights and measures, and was the final arbiter of disputes between the states. Crucially, however, it could not raise any funds and depended entirely on the states for the money necessary to operate. Each state sent a delegation of between two and seven members to the Congress, and they voted as a group with each state getting one vote. But, any decision of consequence required a unanimous vote, which led to a paralyzed and ineffectual government.

A movement to reform the Articles began and in September 1786, commissioners from five states met in the Annapolis Convention to discuss adjustments to the Articles of Confederation. After the debate, the Congress of the Confederation endorsed the plan to revise the Articles of Confederation on February 21, 1787. Invitations to attend a convention in Philadelphia to discuss changes to the Articles were then sent to the state legislatures.

In May 1787, delegates from 12 of the 13 states (Rhode Island sent no representatives) convened in Philadelphia to begin the work of redesigning the government. The delegates to the Constitutional Convention quickly began work on drafting a new Constitution for the United States.

The Constitutional Convention

A chief aim of the Constitution, as drafted by the Convention, was to create a government with enough power to act on a national level but without so much power that fundamental rights would be at risk. One way this was accomplished was to separate the power of government into three branches and then to include checks and balances on those powers to ensure that no one branch of government gained supremacy. This concern arose primarily out of the experience that the delegates had with the King of England and his powerful Parliament. Three main branches of government were defined: the Congressional Legislature, the Senate, and a judicial branch headed by the Supreme Court, and the powers and duties of each branch specified within the Constitution. All powers not assigned were reserved for the respective states and the people, thereby establishing the federal system of government.

Much of the debate, conducted in secret to ensure that delegates spoke their minds, focused on the form the new legislature would take. Two plans competed to become the new government: the Virginia Plan, which apportioned representation based on the population of each state, and the New Jersey plan, which gave each state an equal vote in Congress. The larger states supported the Virginia Plan, and the smaller preferred the New Jersey plan. Ultimately, they settled on the Great Compromise (sometimes called the Connecticut Compromise), in which the House of Representatives would represent the people as apportioned by population, the Senate would represent the states apportioned equally, the Electoral College would elect the President. The plan also called for an independent judiciary.

The founders also took pains to establish the relationship between the states. States are required to give “full faith and credit” to the laws, records, contracts, and judicial proceedings of the other states, although Congress may regulate the manner in which the states share records, and define the scope of this clause. States are barred from discriminating against citizens of other states in any way and cannot enact tariffs against one another. States must also extradite those accused of crimes to other states for trial.

The founders also specified a process by which the Constitution could be amended, and since its ratification, it has been amended 27 times. To prevent arbitrary changes, the process of making amendments is quite arduous. An amendment may be proposed by a two-thirds vote of both Houses of Congress or, if two-thirds of the states request one, by a convention called for that purpose. The amendment must then be ratified by three-fourths of the state legislatures or three-fourths of conventions called in each state for ratification. In modern times, amendments have traditionally specified a timeframe in which this must be accomplished, usually several years. Additionally, the Constitution specifies that no amendment can deny a state equal representation in the Senate without that state’s consent.

With the details and language of the Constitution decided, the Convention got down to the work of actually setting the Constitution to paper. It is written in the hand of a delegate from Pennsylvania, Gouverneur Morris, whose job allowed him some reign over the actual punctuation of a few clauses in the Constitution. He is also credited with the famous preamble, quoted at the top of this page. On September 17, 1787, 39 of the 55 delegates signed the new document, with many who refused to sign objecting to the lack of a bill of rights. At least one delegate refused to sign because the Constitution codified and protected slavery and the slave trade.

Ratification

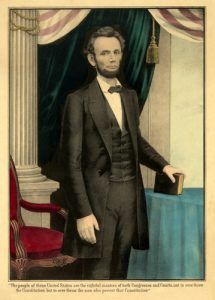

Lincoln’s Constitution quote by E.B. and E.C. Kellogg, 1864.

“The people of these United States are the rightful masters of both congresses and courts, not to overthrow the Constitution, but to over-throw the men who pervert that Constitution.”

The process set out in the Constitution for its ratification provided for much widespread debate in the states. The Constitution would take effect once it had been ratified by nine of the thirteen state legislatures — unanimity was not required. Two factions emerged during the debate over the Constitution: the Federalists, who supported adoption, and the Anti-Federalists, who opposed it.

James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay set out an eloquent defense of the new Constitution in what came to be called the Federalist Papers. Published anonymously in the newspapers The Independent Journal and The New York Packet under the name Publius between October 1787 and August 1788, the 85 articles comprising the Federalist Papers remain an invaluable resource for this day for understanding some of the framers’ intentions for the Constitution. The most famous of the articles are No. 10, which warns of the dangers of factions and advocates a large republic, and No. 51, which explains the structure of the Constitution, its checks and balances, and how it protects the rights of the people.

The states proceeded to begin ratification, with some debating more intensely than others. Delaware was the first state to ratify on December 7, 1787. After New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify on June 21, 1788, the Confederation Congress established March 9, 1789, as the date to begin operating under the Constitution. By this time, all the states except North Carolina and Rhode Island had ratified, but they too followed, with Rhode Island being the last to ratify on May 29, 1790.

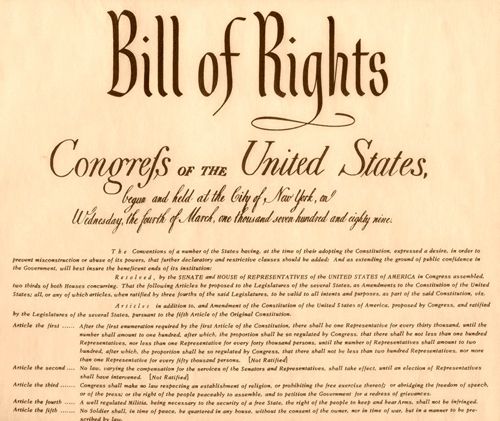

The Bill of Rights

One principal contention between the Federalists and Anti-Federalists was the Constitution’s lack of an enumeration of fundamental civil rights. Many Federalists argued that the people surrendered no rights in adopting the Constitution. In several states, however, the ratification debate hinged on adopting a bill of rights. The solution was known as the Massachusetts Compromise, in which four states ratified the Constitution but, at the same time, sent recommendations for amendments to the Congress.

James Madison introduced 12 amendments to the First Congress in 1789 which were soon to the states for ratification. Designed to protect the civil rights of the people, the bill guaranteed the freedom of speech, press, assembly, the exercise of religion, the right to fair legal procedure, to bear arms, and that powers not delegated to the federal government would be reserved for the states and the people. The Bill of Rights was ratified on December 15, 1791, except for one proposal which dealt with Congressional salaries, which was not ratified until 1992.

The Amendments

The First Amendment provides that Congress make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting its free exercise. It protects freedom of speech, the press, assembly, and the right to petition the government to redress grievances.

The Second Amendment gives citizens the right to bear arms.

The Third Amendment prohibits the government from quartering troops in private homes, a major grievance during the American Revolution.

The Fourth Amendment protects citizens from unreasonable search and seizure. The government may not conduct any searches without a warrant, which must be issued by a judge based on probable cause.

The Fourth Amendment protects citizens from unreasonable search and seizure. The government may not conduct any searches without a warrant, which must be issued by a judge based on probable cause.

The Fifth Amendment provides that citizens not be subject to criminal prosecution and punishment without due process. Citizens may not be tried twice on the same set of facts and are protected from self-incrimination (the right to remain silent). The amendment also establishes the power of eminent domain, ensuring that private property is not seized for public use without just compensation.

The Sixth Amendment assures the right to a speedy trial by a jury of one’s peers, to be informed of the crimes with which they are charged, and to confront the witnesses brought by the government. The amendment also provides the accused the right to compel testimony from witnesses and to legal representation.

The Seventh Amendment provides that civil cases also be tried by a jury.

The Eighth Amendment prohibits excessive bail, excessive fines, and cruel and unusual punishments.

The Ninth Amendment states that the list of rights enumerated in the Constitution is not exhaustive and that the people retain all rights not enumerated.

The Tenth Amendment assigns all powers not delegated to the United States, or prohibited to the states, to either the states or to the people.

In 2004, Senator Robert Byrd introduced an amendment to a spending bill that established September 17 as Constitution Day and Citizenship Day. This federal observance recognizes the adoption of the U.S. Constitution and those who have become U.S. Citizens. Before this law was enacted, September 17 was known as Citizenship Day. Congress mandated through the act that all publicly-funded educational institutions provide education about the Constitution on that day.

The United States Constitution is the shortest and oldest written national Constitution still in use by any nation in the world today.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2023.

Also See:

Source: The White House