This settlement will become one of the finest cities in America.

— Pierre Laclede Liguest, founder of St. Louis, in 1764

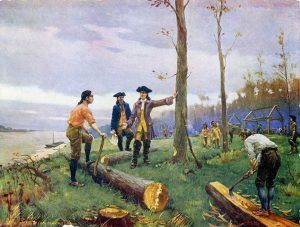

St. Louis, one of the oldest cities in Missouri, began when a man named Pierre Laclede Liguest discovered the perfect place for a trading post on a high bluff of the Mississippi River in 1763. Early the next year, Laclede sent his stepson, along with thirty men, to begin clearing the heavily forested land for a new town, of which Laclede declared, “This settlement will become one of the finest cities in America.”

The first structures included a large house for the fur company’s headquarters, along with cabins and storage sheds. A posthouse was completed in September 1764, becoming the focal point of the new village. From here, streets and buildings soon expanded as trappers and traders populated the settlement. Referred to as Laclede’s Village by its new residents, Laclede himself pronounced the settlement “St. Louis” in honor of King Louis IX of France.

By 1766, the burgeoning village had about 75 buildings built of stone, quarried along the river bluff, or timber posts, and was called home to about 300 residents. Maintaining a steady growth through the end of the century, St. Louis boasted almost 1000 citizens by 1800, mostly French, Spanish, Indians, and both black slaves and free men.

In 1804, when the Louisiana Purchase was officially transferred to the United States, the settlement included a bakery, two taverns, three blacksmiths, two mills, and a doctor. Several grocers also operated from their homes, selling merchandise at outrageous prices due to high transportation costs.

Lewis and Clark.

President Thomas Jefferson sent Lewis & Clark from St. Louis to explore the new Louisiana Territory in May 1804. Two years later, when the explorers returned in September 1806, the city became the “Gateway to the West” for the many mountain men, adventurers, and setters who followed the path of Lewis and Clark into the new frontier.

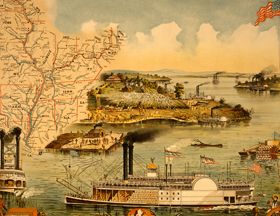

The first steamboat arrived on July 27, 1817, beginning the boomtown days of St. Louis as an important river city. Before long, it was common to see over 100 steamboats lining the cobblestone levee on any given day.

The 1830s were a decade of growth and prosperity along the burgeoning river city. Many new churches were built at this time, a public school system was started, and the city implemented a new water system. By 1840, St. Louis was called home to almost 17,000 residents.

The next decade saw many immigrants populating the city, especially those from Germany and Ireland, driven by the Old World potato famine.

Mississippi River steamboat.

In 1849, St. Louis suffered two major setbacks. The first was a raging fire that destroyed 15 city blocks and 23 steamboats along the riverfront. Later in the same year, St. Louis was to suffer from a serious epidemic of cholera, which took thousands of lives.

By 1850, river traffic had increased to such an extent that St. Louis had become the second-largest port in the country, with commercial tonnage exceeded only by New York. It had also grown to be the largest city west of Pittsburgh. On some days, as many as 170 steamboats, some of which were literally “floating palaces,” could be counted on the levee, complete with chandeliers, lush carpets, and fine furnishings.

During this time, travel to the vast west began in earnest after gold had been discovered in California the prior year. St. Louis saw additional prosperity as the gateway to the west, outfitting many a wagon train, trapper, miner, and trader.

By the time the construction of the railroads began in the early 1850s, St. Louis had a population of almost 80,000 people. The first westbound train left St. Louis in 1855, eventually leading to the death of the riverboat traffic.

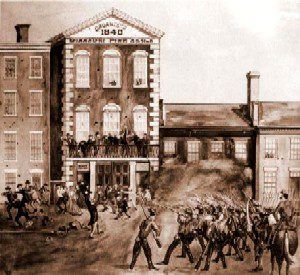

St Louis Arsenal.

When the Civil War began, St. Louis, which had grown to more than 160,000 people, became a divided city where abolitionists shared the streets with slaveholders. While Missouri was primarily in favor of slavery, the state pledged itself to the Union, creating much conflict among its citizens. Moreover, the war caused the cessation of river traffic from the south, devastatingly affecting local businesses and slowing the city’s development.

However, after the war, the city saw another period of major expansion as more and more people fled from the devastated south. St. Louis soon became a major industrial center with numerous clothing and shoe manufacturers and more than 100 breweries operating in the city. The largest brewery, Anheuser-Busch, continues to maintain its world headquarters in St. Louis to this day.

By 1890, the U.S. Census declared that the frontier had closed and America held no more unexplored and undiscovered lands. After this declaration, St. Louis grew at a more leisurely pace, having some 575,000 residents by the turn of the century.

Worlds Fair in St Louis, Missouri, 1904.

In 1904, St. Louis hosted the World’s Fair, the greatest event in its history. Covering more than 1,000 acres near West Forest Park, the fair attracted more than 20 million visitors to the glittering expanse of white palaces and lagoons. That same summer, the United States became the first English-speaking country to host the Olympic Games on the fairgrounds. Bringing worldwide attention to the city, another wave of growth continued in St. Louis, which lasted through World War I.

Though the Great Depression took its toll on St. Louis in much the same manner as other cities, the town bounced back quickly with its wealth of industry and diversification.

When Route 66 came through the city, St. Louis was already more than 150 years old, with well-established streets and neighborhoods. Due to the city’s continued growth and expansion during the life of the Mother Road, the route was changed in St. Louis multiple times. With so many alignments through the metropolis, you’ll need a few good maps to navigate St. Louis in search of vintage Route 66 icons.

Start your journey of the Mother Road through Missouri on the Old Chain of Rocks Bridge, located north of downtown. Crossing the Mississippi River from Illinois to Missouri, the bridge was constructed in 1929 as part of the original Highway 66 project. Initially financed by tolls, the bridge carried passengers over the “Mighty Mo” for the next 38 years until a new bridge was constructed in 1967.

Then, for more than three decades, the bridge sat closed and abandoned in an area that soon developed a reputation for crime and violence. However, in 1999, the bridge was renovated and reopened as a bicycle and pedestrian bridge. Today, the one-mile-long Chain of Rocks Bridge is one of the world’s longest strolling and biking bridges.

After viewing this historic viaduct, head to downtown St. Louis, where you can see the Gateway Arch National Park with the Museum of Westward Expansion and the historic Union Station.

The Eat-Rite Diner at 622 Chouteau Avenue was an icon on the Mother Road. Constructed in 1908 before Route 66 was even conceived, this long-enduring eatery first served as a coffee and donut shop for railroad crews.

In 1940, it became the “Eat-Rite Diner” and coined its motto, “Eat-Rite or don’t eat at all.” Nostalgic Route 66 travelers enjoyed this stop until December 2020, when it became another lost business due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Another “must-see” along the way is Ted Drewes Frozen Custard at 6726 Chippewa, which has been serving up frozen “concretes” to hungry travelers since 1929. In September of 2016, it won the second annual World Ice Cream Index. Not far from Ted Drewes is another old Route 66 landmark – the Donut Drive-In, which also continues to cater to Mother Road travelers today.

At the National Museum of Transportation in southwest St. Louis, you can view a unit of the Coral Court Motel. Moved brick by brick to the museum, this motel once gained a reputation in St. Louis as a “no-tell motel.” Though the historic motel is gone, the museum brings at least a piece of it back to life.

Continue to follow the Route 66 markers along Chippewa and Manchester Roads through the St. Louis suburbs to see numerous vintage motels and diners scattered between busy modern shopping areas.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Ghosts of the Bethlehem Cemetery, St. Louis

Haunted Bissell Mansion in St. Louis

Missouri Route 66 Photo Print Gallery