The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was a law passed by the 31st United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers. The Act was one of the most controversial elements of the 1850 compromise and heightened Northern fears of a slave power conspiracy.

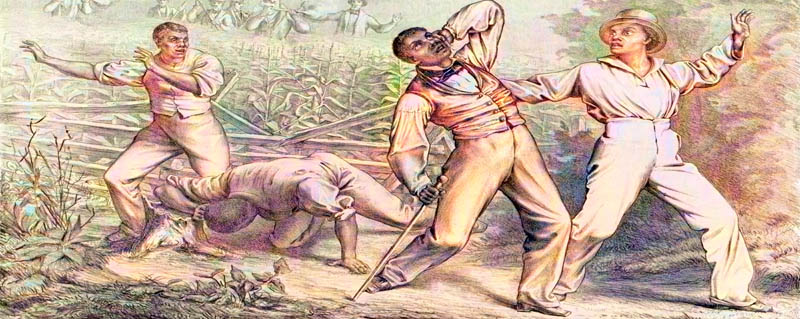

The law provided for the appointment of federal commissioners empowered to issue warrants for the arrest of alleged fugitive slaves and to enlist the aid of posses and even civilian bystanders in their apprehension. Increasing the federal and free-state responsibility for recovering fugitive slaves, the controversial law allowed slave hunters to seize alleged fugitive slaves without due process of law. It prohibited anyone from aiding escaped fugitives or obstructing their recovery. The law threatened the safety of all blacks, slave and free, and forced many Northerners to become more defiant in their support of fugitives.

It required that all escaped slaves, upon capture, be returned to the enslaver and that officials and citizens of free states had to cooperate. The Act contributed to the growing polarization of the country over the issue of slavery. It was one of the factors that led to the Civil War.

Sectional tensions over slavery in America escalated with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, inspiring stiff and sometimes violent resistance from antislavery groups in the North. Opposition to the law took many forms early. For abolitionists, the law provided an opportunity to put slavery at the center of national politics by committing influential and controversial acts of resistance to its enforcement. Their efforts not only helped to drive forward sectional divisions and pave the way for civil war but also helped to secure the freedom of numerous freedom seekers threatened by enslavement.

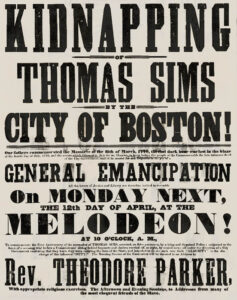

With the passage of the law alongside the Compromise of 1850, freedom seekers were faced with renewed threats of returning to slavery. In response, many fled north, while others evaded capture and remained free. Yet for freedom seekers such as Thomas Sims and Anthony Burns, who were ultimately returned to slavery, their stories ignited tense debates over the constitutionality of the law and the morality of slavery in general.

A year after the passage of the 1850 Act, Thomas Sims escaped from slavery in Chatham County, Georgia, where he was enslaved to James Potter. He traveled north aboard a ship as a stowaway, remaining undetected by the crew for some time. As the ship neared the city of Boston, Massachusetts, a crewmember discovered Sims and informed the captain. Sims escaped from the ship by taking one of its additional boats and went to Boston, where he found refuge for several months.

However, James Potter soon became aware that Sims was in Boston and enlisted a federal marshal’s assistance and several local authorities to capture Sims. They eventually found him on the night of April 3. Upon being captured, Sims raised the cry of ‘kidnappers’ and stoutly resisted being carried into the courthouse to await trial.

Boston had long been a center of abolitionist sentiments, with prominent antislavery residents such as William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips. Abolitionists in Boston, hearing of Sims’ arrest and deeply opposed to the 1850 Act, were eager to secure his escape. Despite devising several attempts to rescue Sims, including a plan for him to jump onto a mattress situated beneath the window of his third-story cell, they were unsuccessful in helping him escape before trial. During the trial, his defense provided a powerful and passionate case against his return to slavery. However, he was ultimately convicted and remanded to Potter.

The return of Sims to slavery witnessed an astonishing spectacle of protest in Boston. Authorities decided to escort Sims to a brig heading for Savannah, Georgia, on the early morning of April 12, during which they hoped few protestors would be present. To prevent Sims from escaping, over 300 local authorities were assigned to help escort him to the ship. Despite the presence of nearly 100 spectators, “the whole affair passed off very quietly” with only “a little hissing.” After reaching the ship successfully, Sims was returned to Georgia, where he remained enslaved for over a decade.

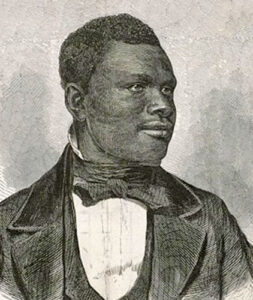

In March 1854, an enslaved man from Virginia, Anthony Burns, escaped slavery and fled to Boston aboard a ship. For two months, Burns found freedom in Boston, but on May 24, he was arrested by a federal marshal while walking in the city. Authorities were made aware of his location after he wrote to his brother from Boston, who was also enslaved in Virginia. The letter was reportedly “dated in ‘Boston,’ but sent to Canada,” revealing his location to his owner, who obtained a warrant for his arrest. He was subsequently imprisoned in the local courthouse to await trial.

Abolitionists in Boston seemed determined to prevent a similar situation to Sims’ from occurring again and quickly devised plans to free him. A meeting of militant abolitionists resolved to free him by force, and on the night of May 26, they attacked the courthouse. There, they proceeded with a long plank, which they used as a battering ram, and two axes to break in and force an entrance. Soon, “pistols were heard in the crowd,” and “rioters fired some thirty shots.” Their attempt was ultimately unsuccessful, however, with the event ending in the death of a federal marshal and the arrests of 13 people.

Burns was brought to trial the following day and convicted, cementing his return to slavery. Anxious over a recurrence of violence, authorities took additional measures to prevent his escape. President Franklin Pierce had earlier approved a detachment of United States troops and others to Boston to prevent further violence and murder. On June 2, Burns was escorted to a ship by hundreds of armed federal soldiers. Outraged protesters lined the streets as the procession slowly marched toward the harbor. “Passing down State Street, the procession was greeted the whole route with mingled groans, cheers, and hisses,” while Burns “appeared as indifferent as the most uninterested spectator.” He was taken aboard the ship and forced back into slavery in Virginia, where he was eventually sold to another enslaver.

Neither Anthony Burns nor Thomas Sims’s story ended after returning to slavery. For Burns, freedom came early. Only a year after the events in Boston, a Baptist preacher in the city led an effort to purchase his freedom, purchasing Burns on February 22, 1855, for $1200. Burns returned to Massachusetts and eventually enrolled at Oberlin College in Ohio “‘ to study for the ministry.'” Oberlin had a vibrant antislavery community; in 1858, abolitionists helped freedom seeker John Price escape slavery and flee to Canada in what became known as the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue. Upon graduating from college, Burns became a pastor at the African American Baptist church in Indianapolis, Indiana, and later moved to Canada to continue his work in the ministry. Burns died in 1862 at the age of only 28, and his story made a lasting mark on American politics and opposition to slavery.

Thomas Sims remained enslaved until 1863, when, during the Civil War, he escaped from Vicksburg, Mississippi, in a dugout, having on board his wife, child, and four men, into the Union lines of General Ulysses S. Grant. He provided details of Confederate positions and fortifications after returning to Boston. In 1877, U.S. Attorney General Charles Devens appointed Sims as a messenger in the U.S. Department of Justice. Devens previously crossed paths with Sims as a U.S. Marshal when he assisted in his arrest in 1851, an event Devens reportedly recalled “with pain.” Sims later died in 1902. Like Anthony Burns before him, he left a legacy as an important figure in the resistance to the 1850 Act and opposition to slavery in general.

Many abolitionists openly defied the law. Reverend Luther Lee, pastor of the Wesleyan Methodist Church of Syracuse, New York, wrote in 1855:

“I never would obey it. I had assisted thirty slaves to escape to Canada during the last month. If the authorities wanted anything of me, my residence was at 39 Onondaga Street. I would admit that, and they could take me and lock me up in the Penitentiary on the hill, but if they did such a foolish thing as that, I had friends enough in Onondaga County to level it to the ground before the next morning.”

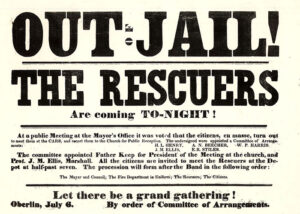

Among the most famous cases of resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act was the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue of 1858. Inspired by the Christiana Riot of 1851 seven years earlier, an incident in Ohio further tore apart the already delicate sectional fabric between North and South. What was later referred to as the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue began when John Price, enslaved to Kentucky slaveholder John G. Bacon, escaped to Oberlin, Ohio, in 1856, which the New York Herald described as “a well-known antislavery town.” For two years, Price found refuge in Oberlin until he was arrested on September 13, 1858, by a federal marshal. After being captured, Price was taken by train south of Oberlin to Wellington, Ohio, where the marshal encamped in a local hotel before planning to enter Kentucky.

Abolitionists and other antislavery advocates in Oberlin rallied to Price’s defense. After hearing that “someone had been kidnapped,” abolitionists resolved to journey to Wellington and secure his freedom. “We will have the man,” said one person defiantly, “law or no law.” After reaching the hotel in Wellington, the antislavery crowd attempted to peacefully negotiate Price’s return before resorting to force. The marshal inside the hotel refused their pleas. Just then, there was a rush; the window was broken, and several men swept into the room where Price was being held, helping him escape and return to Oberlin. Once in Oberlin, those involved in his rescue acted quickly to secure Price’s escape to Canada, where he successfully found freedom.

While the citizens of Wellington resolved that they would “resist, for the future, any and every attempt to arrest a negro at Oberlin,” authorities moved to convict those involved with the rescue. Of the people involved with Price’s escape, 37 were indicted by a federal grand jury for having violated the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Authorities in Ohio, sympathetic to the rescuers and opposed to many provisions of the Act, reacted by arresting the federal marshal and other officers who captured Price, charging them with kidnapping. By April of 1859, federal and state authorities negotiated the release of both parties, with only two antislavery men being convicted and the remaining 35 released without charges. In return, Ohio authorities dropped the charges of kidnapping.

Defiant and determined to push back against federal enforcement of the 1850 Act, the convicted men, Simon Bushnell and Charles Langston, filed a writ of habeas corpus with the Ohio Supreme Court while claiming the Act was itself unconstitutional. The Ohio Court refused their application for writs of habeas corpus, upholding the constitutionality of the Act. That same year, the Supreme Court struck down a similar case in Wisconsin, where the state supreme court declared the 1850 Act unconstitutional and attempted to nullify its enforcement.

Occurring at a time in which the country was fiercely divided over the issue of slavery, the events in Oberlin and Wellington became another major flashpoint of political conflict. For many involved with the abolitionist movement, the incident was a cause for celebration. Frederick Douglass described Oberlin in religious oratory as a “Gibraltar of Freedom,” a haven where the “infamous” Fugitive Slave Act could not be enforced. Others portrayed the trial against the antislavery group as evidence that “the general government is under the control of slaveholders.” At once commended by abolitionists and condemned by enslavers, the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue exposed the irreconcilable divisions between North and South that, within three years, erupted into civil war.

Other famous examples included Shadrach Minkins in 1851 and Lucy Bagby in 1861, whose forcible return historians have cited as necessary and “allegorical.” Pittsburgh abolitionists organized groups whose purpose was the seizure and release of any enslaved person passing through the city, as in the case of a free Black servant of the Slaymaker family, erroneously the subject of a rescue by Black waiters in a hotel dining room. If fugitives from slavery were captured and put on trial, abolitionists worked to defend them in trial. If, by chance, the recaptured person had their freedom put up for a price, abolitionists worked to pay to free them. Other opponents, such as African American leader Harriet Tubman, treated the law as another complication in their activities.

In April 1859, a putative freeman named Daniel Webster was arrested in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, alleged to be Daniel Dangerfield, an escaped slave from Loudoun County, Virginia. At a hearing in Philadelphia, federal commissioner J. Cooke Longstreth ordered Webster’s release, arguing the claimants had not proved that he was Dangerfield. Webster promptly left for Canada.

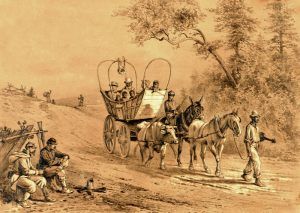

In the early stages of the Civil War, the Union had no established policy on people escaping from slavery. Many enslaved people left their plantations, heading for Union lines. Still, in the early stages of the war, fugitives from slavery were often returned by Union forces to their enslavers. General Benjamin Butler and some other Union generals, however, refused to recapture fugitives under the law because the Union and the Confederacy were at war. He confiscated enslaved people as contraband of war and set them free, with the justification that the loss of labor would also damage the Confederacy. President Abraham Lincoln allowed Butler to continue his policy but countermanded broader directives issued by other Union commanders that freed all enslaved people in places under their control.

In August 1861, the U.S. Congress enacted the Confiscation Act of 1861, which barred enslavers from re-enslaving captured fugitives who were forced to aid or abet the insurrection. The legislation, sponsored by Lyman Trumbull, was passed on a near-unanimous vote and established military emancipation as official Union policy, but applied only to enslaved people used by rebel enslavers to support the Confederate cause, creating a limited exception to the Fugitive Slave Act.

Union Army forces sometimes returned fugitives from slavery to enslavers until March 1862, when Congress enacted the Confiscation Act of 1862, which barred Union officers from returning slaves to their owners on pain of dismissal from the service. James Mitchell Ashley proposed legislation to repeal the Fugitive Slave Act, but the bill did not make it out of committee in 1863. Although the Union policy of confiscation and military emancipation had effectively superseded the operation of the Fugitive Slave Act, the Fugitive Slave Act was only formally repealed in June 1864. The New York Tribune hailed the repeal:

“The blood-red stain that has blotted the statute book of the Republic is wiped out forever.”

Finally, the 13th Amendment to the Constitution declared that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” The amendment formally abolished slavery in the United States. It was passed by Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified by the states on December 6, 1865.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, March 2024.

Also See:

African Americans – From Slavery to Equality

Sources:

González, Jennifer; Escaping Slavery: The Consequences of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Library of Congress

González, Jennifer; Law or No Law: Abolitionist Resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Library of Congress

Wikipedia