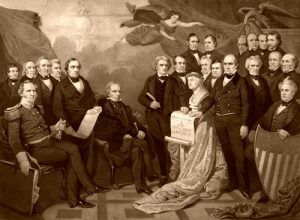

The Union, a symbolic group portrait eulogizing legislative efforts, including the Compromise of 1850, to preserve the Union, by Tompkins H. Matteson.

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 was an effort by Congress to defuse political rivalries and maintain the balance of power between the North and South.

In the years leading up to the Missouri Compromise, tensions had been building between pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions across the country and within the U.S. Congress. When Missouri requested admission to the Union as a slave state in 1819, it threatened to upset the delicate balance between slave and free states. At the time, the United States contained 22 states, evenly divided between slave and free.

At about the same time, the state of Maine was also requesting admission to the Union. The Missouri Compromise was reached to keep the peace, which granted Missouri’s request and admitted Maine as a free state. The compromise also drew an imaginary line across the former Louisiana Territory, which prohibited slavery north of the 36°30′ parallel, excluding Missouri. The Missouri Compromise remained the law of the land until it was negated by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854.

Though the compromise had been made, the bitter disputes in gaining the agreement led to intense competition between the southern and northern states for power in Congress and control over future territories. The changes of the next 30 years gradually increased and intensified the antagonism of sentiment between the North and South.

With the simultaneous admission of Michigan and Arkansas in 1836 and Iowa and Florida in 1845, the numerical equality of the free and slave states continued. But, the request for annexation of Texas brought the embers of Northern discontent, which had smoldered since the days of the Missouri contest, again to a white heat. Texas claimed a country over which she had never established jurisdiction, and its boundaries were still disputed with the Mexican Republic. It was well understood that to annex Texas, with her boundaries in dispute, war with Mexico was inevitable. Further, it was no secret that the whole project was in the interest of slavery. Nevertheless, the annexation was completed on March 2, 1845.

The only redeeming feature for the Northerners was in recognition of the compromise line of 36° 30′, north of which slavery was prohibited, and the possibility of new territories in the region. During the Mexican-American War, the North was subjected to the deeper humiliation of fighting to win territory from Mexico to increase the domain of slaveholding Texas.

Tension remained during a series of bills aimed at resolving the territorial and slavery controversies, including the drafting of several laws that balanced the interests of the slave states of the South and the free states of the North. Subsequently, California was admitted as a free state. Texas received financial compensation for relinquishing its claim to lands west of the Rio Grande in what would become New Mexico Territory, which was organized without any specific prohibition of slavery.

At the inauguration of President Franklin Pierce on March 4, 1853, all visible indications were favorable for a period of political calm and national prosperity. Despite the continued denunciations of, and occasional resistance to, the fugitive slave law in the North and the secret plottings of Southern secessionists, the great majority in both the North and South were hopeful that, based on the compromises of 1850, the Union, at last, rested on a firm foundation.

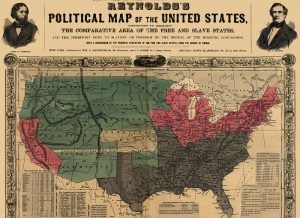

1856 map showing slave states in gray, free states in pink, U.S. territories in green, and Kansas in white.

However, that would change when petitions were presented at the first session of the 32nd Congress for a territorial organization of the region lying west of Missouri and Iowa. The initial purpose of the Kansas-Nebraska Act was to create opportunities for a transcontinental railroad. However, the proposed bill once again brought the tensions to a head when it was met by an unexpected and formidable opposition from the Southern members, who recommended it be rejected. The uncompromising opposition from Southern members refused the organization of any “free-state” territories until a division of the slave State of Texas or other means might present an equal plan.

On January 23, 1854, Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois submitted a substitute bill, providing for two territories instead of one—the northern territory to be called “Nebraska” and the southern one “Kansas.” Douglas hoped to gain Southerners’ support by assuming that the more northern territory would oppose slavery while the southern one would permit it.

After a long and bitter discussion, the Kansas-Nebraska Act repealed the Missouri Compromise, opened up Kansas and Nebraska territories, and allowed the settlers to determine by vote whether the states would be free or slaveholding. President Pierce signed the act on May 30, 1854.

Southerners and pro-slavery men, mainly from Missouri, soon flooded Kansas, intending to vote for slavery. Alternatively, abolitionists and Emigrant Aid Societies came from the North to ensure the state would reject slavery. For the next seven years, an internal civil war would be fought in Kansas over the issue, resulting in the territory earning the nickname “Bleeding Kansas” as the death toll rose. Eventually, the anti-slavery settlers outnumbered pro-slavery settlers, and on January 29, 1861, just before the Civil War, Kansas was admitted to the Union as a free state.

Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated April 2024.

Also See:

Photo Galleries of the Civil War

Sources:

Blackmar, Frank W., Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912

History.com

Kansas-Nebraska Act

Wikipedia