“How d’ do?” Hobbs replied, thinking it would be better to be as polite as the Indian, though the state of the latter’s health just then was a matter of small concern.

“Texas?” inquired the Indian. The Comanche had good reasons to hate the citizens of that country, and it was a lucky thing for Hobbs that he had heard of their prejudice from the trappers and possessed the presence of mind to remember it. He replied promptly: “No, friendly; going to establish a trading post for the Comanche.”

“Friendly? Better go with us, though. Got any tobacco?”

Hobbs had some of the desired articles, and he was not long in handing them over to his newly found friend.

Both of the boys were escorted to the temporary camp of the Indians, but the original number of their captors was increased to over a thousand before they arrived there. They were supplied with some dried buffalo meat and then taken to Old Wolf’s lodge, the head chief of the tribe.

A council was called immediately to consider what disposition should be made of them, but nothing was decided upon, and the assembly of warriors adjourned until morning. Hobbs told me that it was because Old Wolf had imbibed too much brandy, a bottle of which Baptiste had brought with him from the train and which the thirsty warrior saw suspended from his saddle bow as they rode up to the chief’s lodge; the aged rascal got beastly drunk.

About noon of the next day, after the dispersion of the council, the boys were informed that if they were not Texans, would behave themselves, and not attempt to run away, they might stay with the Indians, who would not kill them; but a string of dried scalps was pointed out, hanging on a lodgepole, of some Mexicans whom they had captured and put to herding their ponies, and who had tried to get away. They succeeded in making a few miles; the Indians chased them after deciding in council that, if caught, only their scalps were to be brought back. The moral of this was that the same fate awaited the boys if they followed the foolish Mexicans’ example.

Hobbs had excellent sense and judgment, and he knew that it would be the height of folly for him and Baptiste, mere boys, to try and reach either Bent’s Fort, Colorado or the Missouri River, not having the slightest knowledge of where they were situated.

Hobbs grew to be a great favorite with the Comanche; was given the daughter of Old Wolf in marriage, became a great chief, fought many hard battles with his savage companions, and at last, four years after, was redeemed by Charles Bent, who paid Old Wolf a small ransom for him at the Fort, where the Indians had come to trade. Baptiste, whom the Indians never took a great fancy to because he did not develop into a great warrior, was also ransomed by Bent, his price being only an antiquated mule.

At Bent’s Fort, Hobbs went out trapping under Kit Carson’s leadership, and they became lifelong friends. In a short time, Hobbs earned the reputation of being an excellent mountaineer, trapper, and as an Indian fighter, he was second to none, his education among the Comanche having trained him in all the strategies of the Indians.

After going through the Mexican War with an excellent record, Hobbs wandered about the country, now engaged in mining in old Mexico, then fighting the Apache under the orders of the governor of Chihuahua, and at the end of the campaign going back to the Pacific coast, where he entered into new pursuits. Sometimes he was rich, then as poor as one can imagine. He returned to old Mexico in time to become an active partisan in the revolt which overthrew the short-lived dynasty of Maximilian and was present at the execution of that unfortunate prince. Finally, he retired to the home of his childhood in the States, where he died a few months ago, full of years and honors.

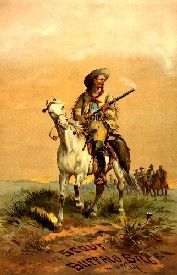

William F. Cody, “Buffalo Bill,” is one of the famous plainsmen, of later days, after Carson, Bridger, John Smith, Maxwell, and others. Perhaps, Kit Carson’s mantle fits more perfectly the shoulders of Cody than any of the great frontiersman’s successors, and he has had some experiences that surpassed anything that fell to their lot.

He was born in Iowa in 1845, and when barely seven years old, his father emigrated to Kansas, then far from civilization. When he grew old enough, he went to work as a guide and scout in an expedition against the Kiowa and Comanche, and his line of duty took him along the Santa Fe Trail. When not working as a scout, he carried dispatches between Fort Lyon, Colorado, and Fort Larned, Kansas, the most important military posts on the great highway, as well as to far-off Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, on the Missouri River, was the headquarters of the department. Fort Larned was the general rendezvous of all the scouts on the Kansas and Colorado plains, the chief of whom was a veteran interpreter and guide named Dick Curtis.

When Cody first reported there for his responsible duty, a large camp of the Kiowa and Comanche was established within sight of the fort, whose warriors had not yet put on their war paint but were evidently restless and discontented under the restraint of their chiefs. Soon those leading men, Satanta, Lone Wolf, Satank, and others of lesser note, grew rather impudent and haughty in their department, and they were watched with much concern. The post was garrisoned by only two infantry companies and one cavalry.

General Hazen, afterward chief of the signal service in Washington, was at Fort Larned at the time, endeavoring to patch up a peace with the Indians, who seemed determined to break out. Cody was a special scout to the general. One morning he was ordered to accompany him as far as Fort Zarah, Kansas, on the Arkansas River, near the mouth of Walnut Creek, in what is now Barton County, Kansas, the general intended to go on to Fort Harker, on the Smoky Hill River in Kansas. In making these inspection trips, with incidental collateral duties, the general usually traveled in an ambulance, but on this journey, he rode in a six-mule army wagon, escorted by a detachment of a score of infantry. It was a warm August day, and an early start was made, which enabled them to reach Fort Zarah, over thirty miles distant, by noon. After dinner, the general proposed going to Fort Harker, Kansas, 41 miles away, without an escort, leaving orders for Cody to return to Fort Larned the next day with the soldiers. But Cody, ever impatient of delay when there was work to do, notified the sergeant in charge of the men that he was going back that very afternoon. I tell the story of his trip as he has often told it to me and written it in his autobiography.

“I accordingly saddled up my mule and set out for Fort Larned. I proceeded uninterruptedly until I got about halfway between the two posts, when, at Pawnee Rock, I was suddenly jumped by about forty Indians, who came dashing up to me, extending their hands and saying, ‘How! How!’ They were some of the Indians who had been hanging around Fort Larned in the morning. I saw they had on their war paint and were evidently now out on the war path.

“My first impulse was to shake hands with them, as they seemed so desirous of it. I accordingly reached out my hand to one of them, who grasped it with a tight grip and jerked me violently forward; then pulled my mule by the bridle, and I was completely surrounded in a moment. Before I could do anything, they had seized my revolvers from the holsters, and I received a blow on the head from a tomahawk, which nearly rendered me senseless. My gun, which was lying across the saddle, was snatched from its place. Finally, the Indian who had hold of the bridle started toward the Arkansas River, leading the mule, which was being lashed by the other Indians who were following. The Indians were all singing, yelling, and whooping, as only Indians can do when they are having their little game all their own way. While looking toward the river, I saw an immense village moving along the bank on the opposite side, and then I became convinced that the Indians had left the post and were now starting on the war path. My captors crossed the stream with me, and as we waded through the shallow water, they continued to lash the mule and myself. Finally, they brought me before an important-looking body of Indians, who proved to be the chiefs and principal warriors. I soon recognized old Satanta among them, as well as others I knew, and supposed it was all over with me.

“The Indians were jabbering away so rapidly among themselves that I could not understand what they were saying. Satanta, at last, asked me where I had been. As good luck would have it, a happy thought struck me. I told him I had been after a herd of cattle, or ‘ whoa-haws,’ as they called them. It so happened that the Indians had been out of meat for several weeks, as the large herd of cattle that had been promised them had not yet arrived, although they expected them.

“The moment I mentioned that I had been searching for ‘whoa-haws,’ old Satanta began questioning me in a very eager manner. He asked me where the cattle were, and I replied that they were back a few miles and that General Hazen had sent me to inform him that the cattle were coming and that they were intended for his people. This seemed to please the old rascal, who also wanted to know if there were any soldiers with the herd, and my reply was that there were. Thereupon the chiefs consulted, and presently Satanta asked me if General Hazen had really said they should have the cattle. I replied in the affirmative and added that I had been directed to bring the cattle to them. I followed this up with a very dignified inquiry, asking why his young men had treated me so. The old wretch intimated that it was only a ‘ freak of the boys ‘; that the young men wanted to see if I was brave; in fact, they had only meant to test me, and the whole thing was a joke.

“The veteran liar was now beating me at my own game of lying, but I was very glad, as it was in my favor. I did not let him suspect that I doubted his veracity, but I remarked that it was a rough way to treat friends. He immediately ordered his young men to give back my arms and scolded them for their actions. Of course, the sly old dog was now playing it very fine, as he was anxious to get possession of the cattle, with which he believed there was a ‘heap’ of soldiers coming. He had concluded it was not best to fight the soldiers if he could get the cattle peaceably.

“Another council was held by the chiefs, and in a few minutes, old Satanta came and asked me if I would go to the river and bring the cattle down to the opposite side so that they could get them. I replied, ‘Of course; that’s my instruction from General Hazen.’

“Satanta said I must not feel angry at his young men, for they had only been acting in fun. He then inquired if I wished any of his men to accompany me to the cattle herd. I replied that it would be better for me to go alone, and then the soldiers could keep right on to Fort Larned while I could drive the herd down to the bottom. Then wheeling my mule around, I was soon recrossing the river, leaving old Satanta in the firm belief that I had told him a straight story and that I was going for the cattle which existed only in my imagination.

“I hardly knew what to do but thought that if I could get the river between the Indians and myself, I would have a good three-quarter of a mile the start of them and could then make a run for Fort Larned, as my mule was a good one.

“Thus far, my cattle story had panned out all right, but just as I reached the opposite bank of the river, I looked behind me and saw that ten or fifteen Indians, who had begun to suspect something crooked, were following me. The moment that my mule secured a good foothold on the bank, I urged him into a gentle lope toward the place where, according to my statement, the cattle were to be brought. Upon reaching a little ridge and riding down the other side out of view, I turned my mule and headed him westward for Fort Larned. I let him out for all he was worth, and when I came out on a little rise of ground, I looked back and saw the Indian village in plain sight. My pursuers were now on the ridge I had passed over and looking for me in every direction.

“Presently, they spied me, and seeing that I was running away, they struck out in swift pursuit, and in a few minutes, it became painfully evident they were gaining on me. They kept up the chase as far as Ash Creek, six miles from Fort Larned. I still led them half a mile, as their horses had not gained much during the last half of the race. My mule seemed to have gotten his second wind, and as I was on the old road, I played the spurs and whip on him without much cessation; the Indians likewise urged their steeds to the utmost.

“Finally, upon reaching the dividing ridge between Ash Creek and Pawnee Fork, I saw Fort Larned only four miles away. It was now sundown, and I heard the evening gun. The troops of the small garrison little dreamed a man was flying for his life and trying to reach the post. The Indians were once more gaining on me, and when I crossed the Pawnee Fork two miles from the post, two or three of them were only a quarter of a mile behind me. Just as I gained the opposite bank of the stream, I was overjoyed to see some soldiers in a government wagon only a short distance off. I yelled at the top of my voice, and riding up to them, told them that the Indians were after me.

“‘Denver Jim,’ a well-known scout, asked me how many there were, and upon my informing him that there was about a dozen, he said: ‘Let’s drive the wagon into the trees, and we’ll lay for ’em.’ The team was hurriedly driven among the trees and low box-elder bushes and there secreted.

“We did not have to wait long for the Indians, who came dashing up, lashing their ponies, which were panting and blowing. We let two of them pass by, but we opened a lively fire on the next three or four, killing two at the first crack. The others following discovered that they had run into an ambush, and whirling off into the brush, they turned and ran back in the direction whence they had come. The two who had passed by heard the firing and made their escape. We scalped the two we had killed and appropriated their arms and equipment; then, catching their ponies, we made our way into the Post.”

By Colonel Henry Inman, 1897. Compiled and Edited by Kathy Slrcsnfer/Legends of America, updated November 2022.

Also See:

Early Traders on the Santa Fe Trail

Overland Mail on the Santa Fe Trail

Santa Fe Trail – Highway to the Southwest

About the Author: Excerpted from the book, The Old Santa Fe Trail, by Colonel Henry Inman, 1897. Note: The text is not verbatim, as minor edits have been made throughout the tale. Henry Inman was well known both as an officer in the U.S. Army and an author dealing with subjects of the Western plains. During the Civil War, Inman was a Lieutenant Colonel and afterward, he won distinction as a magazine writer. He wrote several books including his Old Santa Fe Trail, Great Salt Lake Trail, The Ranch on the Ox-hide, and other similar books dealing with the subjects he knew so well. Colonel Inman left a number of unfinished manuscripts at his death in Topeka, Kansas on November 13, 1899.