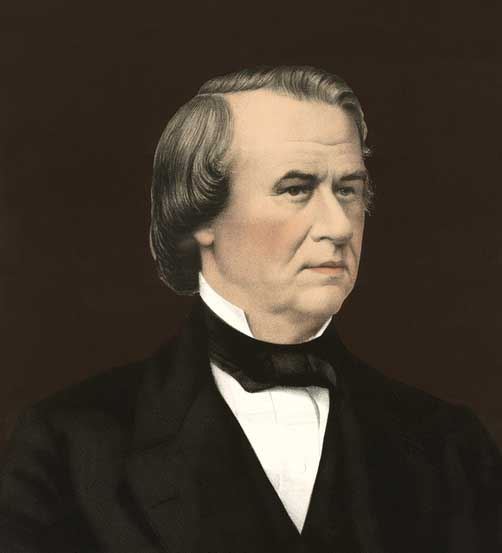

Andrew Johnson was the 17th U.S. President following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. Johnson presided over Reconstruction in the four years following the Civil War. His position favoring the white South came under heavy political attack. His vetoes of civil rights bills embroiled him in a bitter dispute with Radical Republicans, ultimately resulting in him becoming the first President to be impeached. However, he was found to be not guilty.

Born in Raleigh, North Carolina, to Jacob and Mary McDonough Johnson, his father died when he was three years old, leaving the family in poverty. His mother then took in work spinning and weaving to support the family and later remarried. He received no formal education, and when he was a young teenager, his mother bound him as an apprentice tailor in Laurens, South Carolina. Somehow, the boy taught himself how to read and write. At about the age of 16, he left the apprenticeship and ran away with his brother to Greeneville, Tennessee, where he found work as a tailor. Later, he opened his own tailor shop and married Eliza McCardle in 1827 at the age of 19, and the two would eventually have five children. His wife, Eliza, taught him arithmetic up to basic algebra and tutored him to improve his literacy and writing skills.

While in Greenville, he began participating in debates at the local academy and later organized a worker’s party that elected him as an alderman in 1829. He served in this position until he was elected Greenville Mayor in 1833. He was elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives two years later, but after serving just one term, he was defeated for re-election.

He then became a spokesman for the farmers and mountaineers against the wealthier but fewer elite planter families that had held political control in Tennessee. In 1839, he was once again elected to the Tennessee House and was elected to the Tennessee Senate in 1841. In 1843, he was elected as a U.S. Representative, advocating “a free farm for the poor” bill, in which farms would be given to landless farmers. He served as a U.S. representative for five terms until 1853, when he was elected Governor of Tennessee.

During the secession crisis, Johnson remained in the Senate even when Tennessee seceded, which made him a hero in the North and a traitor in the eyes of most Southerners. In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln appointed him Military Governor of Tennessee, and Johnson used the state as a laboratory for Reconstruction. In 1864, Johnson was given the second place on the Republican ticket, partly to reward him for his fidelity to the Union cause in the seceding state of Tennessee and to save the Republican Party from the reproach of being called “sectional” in again choosing both its candidates from Northern states, as it had done in 1856 and 1860.

With the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in April of 1865, the Presidency fell upon the old-fashioned southern Democrat, who, although he had supported abolition, was not an advocate of black rights. Arrayed against him were the Radical Republicans in Congress, brilliantly led and ruthless in their tactics. Johnson was no match for them.

Long before the close of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln had laid out a plan for Reconstruction based on the theory that not the states themselves but combinations of individuals in the states too powerful to be dealt with by the ordinary process of the courts, had resisted the authority of the United States. He had, therefore, welcomed and nursed every manifestation of loyalty in the Southern states. He had recognized the representatives of the small Unionist population of Virginia, assembled at Alexandria within the Federal lines, as the true government of the state. He had immediately established a military government in Tennessee on the success of the Union arms there in the spring of 1862. By a proclamation in December 1863, he had declared that as soon as 10% of the voters in any of the seceded states should form a loyal government and accept the legislation of Congress on the subject of slavery, he would recognize that government as legal. Such governments had been set up in Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana. However, Lincoln disagreed with Congress about the final method of restoring the Southern states to their place in the Union. That question waited till the close of the war, and the awful pity is that when it came, Abraham Lincoln was no longer alive.

During the summer and autumn of 1865, when Congress was not in session, President Andrew Johnson proceeded to apply Lincoln’s plan to the states of the South, just as if it had been settled that Congress was to have no part in their Reconstruction. He appointed military governors in North and South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas. He ordered conventions to be held in those states, which repealed the ordinances of secession and framed new constitutions. State officers were elected, and Legislatures were chosen, repudiating the debts incurred during the war (except in South Carolina) and ratifying the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery (except in Mississippi). When Congress met in December 1865, senators and representatives from the Southern states, which, but a few months before, had been in rebellion against the authority of the United States, were waiting at the doors of the Capitol for admission to their seats.

When Congress met in December 1865, most southern states were reconstructed, and slavery was being abolished; however, “black codes” to regulate the freedmen were beginning to appear. Radical Republicans in Congress moved vigorously to change Johnson’s program. They gained the support of northerners, who were dismayed to see Southerners keeping many prewar leaders and imposing many prewar restrictions upon the blacks.

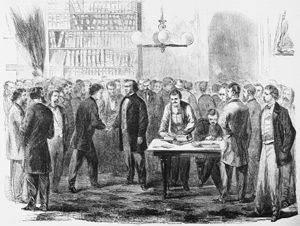

The Radicals’ first step was to refuse to seat any Senator or Representative from the old Confederacy. Next, they passed measures dealing with the former slaves, but Johnson vetoed the legislation. The Radicals mustered enough votes in Congress to pass legislation over his veto — the first time that Congress had overridden a President on an important bill. They passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, establishing African Americans as American citizens and forbidding discrimination against them. A few months later, Congress submitted the Fourteenth Amendment to the states, which specified that no state should “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

All the former Confederate States except Tennessee refused to ratify the amendment; further, there were two bloody race riots in the South. Speaking in the Middle West, Johnson faced hostile audiences. The Radical Republicans won an overwhelming victory in Congressional elections that fall.

In March 1867, the Radicals effected their own plan of Reconstruction, again placing southern states under military rule. They passed laws placing restrictions upon the President. When Johnson allegedly violated one of these, the Tenure of Office Act, by dismissing Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, the House voted eleven articles of impeachment against him on February 24, 1868. This made Johnson the first sitting U.S. President to be impeached; however, he was tried by the Senate starting on March 5, 1868, and acquitted on May 16. The final vote was 35 “guilty” and 19 “not guilty,” one vote shy of the two-thirds majority needed.

Johnson did not run for re-election as president in 1868; instead, he ran as a senate candidate from Tennessee. His bid was unsuccessful, and his bid for the House of Representatives in 1872. However, in 1874, he was elected to the U.S. Senate and served until his death of a stroke on July 31, 1875. He is buried at the Andrew Johnson National Cemetery in Greeneville, Tennessee.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2023.

Also See:

The Era of Reconstruction – How Johnson’s sympathetic policies to the South caused more significant harm and delayed civil rights and the nation’s healing.

Presidents of the United States