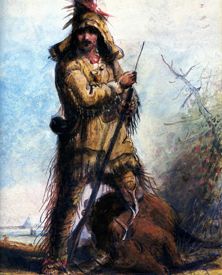

Old Bill Williams by Alfred Jacob Miller, 1839

Old Bill Williams was another character of the early days of the Santa Fe Trail and was called so when Carson, Uncle Dick Wooten, and Maxwell were comparatively young in the mountains. At the time of their advent in the remote West, he was one of the best-known men there and had been famous for years as a hunter and trapper. Williams was better acquainted with every pass in the Rockies than any other man of his time and only surpassed by Jim Bridger later. He was with General John C. Fremont on his exploring expedition across the continent, but the statement of the old trappers, and that of General Fremont, in relation to his services then, differ widely. Fremont admits Williams’ knowledge of the country over which he had wandered to have been very extensive, but when put to the test on the expedition, he came very near, sacrificing the lives of all. This was probably owing to Williams’ failing intellect, for when he joined the great explorer, he was past the meridian of life. Now the old mountaineers contend that if Fremont had profited by the old man’s advice, he would never have run into the deathtrap which cost him three men, and in which he lost all his valuable papers, his instruments, and the animals which he and his party were riding. The expedition had followed the Arkansas River to its source, and the general had selected a route that he desired to pursue in crossing the mountains. It was winter, and Williams explained to him that it was perfectly impracticable to get over at that season. However, the general ignored the statement and listened to another of his party, a man who had no experience but said he could pilot the expedition. Before they had fairly started, they were caught in one of the most terrible snowstorms the region had ever witnessed, in which all their horses and mules were literally frozen to death. Then, when it was too late, they turned back, abandoning their instruments and able only to carry along a very limited stock of food. The storm continued to rage so that even Williams failed to prevent them from getting lost. They wandered about aimlessly for many days before they luckily arrived at Taos, New Mexico, suffering seriously from exhaustion and hunger. Three of the men were frozen to death on the return trip, and the remaining 15 were little better than dead when Uncle Dick Wooten happened to run across them and piloted them into the village. Immediately after this disaster, the three most noted men in the mountains — Carson, Maxwell, and Dick Owens — became the guides of the pathfinder, with whom he had no trouble, and to whom he owed more of his success than history has given them credit for.

At one period of his eventful career, while he lived in Missouri before he wandered to the mountains, Old Bill Williams was a Methodist preacher, of which fact he frequently boasted while he trapped and hunted with other pioneers. Whenever he related that portion of his early life, he declared that he “was so well known in his circuit, that the chickens recognized him as he came riding by the scattered farmhouses, and the old roosters would crow ‘Here comes Parson Williams! One of us must be made ready for dinner.'”

Upon leaving the States, he traveled extensively among the various tribes of Indians who roamed the Great Plains and in the mountains. When sojourning with a certain band, he would invariably adopt their manners and customs. Whenever he grew tired of that nation, he would seek another and live as they lived. He had been so long among the Indians that he looked and talked like one and had imbibed many of their strange notions and curious superstitions.

To the missionaries, he was very useful. He possessed the faculty of easily acquiring languages that other white men failed to learn and could readily translate the Bible into several Indian dialects. However, his own conduct was in strange contrast with the precepts of the Holy Book with which he was so familiar.

To the native Mexicans, he was a holy terror and an unsolvable riddle. They thought him possessed of an evil spirit. He, at one time, took up his residence among them and commenced to trade. Shortly after he had established himself and gathered a stock of goods, he became involved in a dispute with some of his customers about his prices. Upon this, he apparently took an intense dislike to the people whom he had begun to traffic with and, in his disgust, tossed his whole mass of goods into the street and, taking up his rifle, left at once for the mountains.

Among the many wild ideas he had imbibed from his long association with the Indians was faith in their belief in souls’ transmigration. He used so to worry his brain for hours cogitating upon this intricate problem concerning a future state that he pretended to know exactly the animal whose place he was destined to fill in the world after he had shaken off this mortal human coil.

Uncle Dick Wootton told how once, when he, Old Bill Williams, and many other trappers, were lying around the camp-fire one night, the strange fellow, in a preaching style of delivery, related to them all how he was to be changed into a buck elk and intended to make his pasture in the very region where they then were. He described certain peculiarities which would distinguish him from the common run of elk and was very careful to caution all those present never to shoot such an animal, should they ever run across him.

Williams was regarded as a warm-hearted, brave, and generous man. He was at last killed by the Indians while trading with them but has left his name to many mountain peaks, rivers, and passes discovered by him.

Tom Tobin, frontiersman

Tom Tobin, one of the last of the famous trappers, hunters, and Indian fighters to cross the dark river, flourished in the early days when the Rocky Mountains were a veritable terra incognita to nearly all excepting the hardy employees of the several fur companies and the limited number of United States troops stationed in their remote wilds.

Tom was an Irishman, quick-tempered, and a dead shot with either rifle, revolver, or the formidable bowie-knife. He would fight at the drop of a hat, but no man ever went away from his cabin hungry, if he had a crust to divide, or penniless if anything was remaining in his purse. Like Carson, he was rather under the average stature, red-faced, and lacking much of being an Adonis but whole-souled and as quick in his movements as an antelope.

Tobin played an important role in avenging the death of the Americans killed in the Taos Massacre at the storming of the Indian pueblo, but his greatest achievement was the ending of the noted bandit Espinosa’s life, who, at the height of his career of blood, was the terror of the whole mountain region.

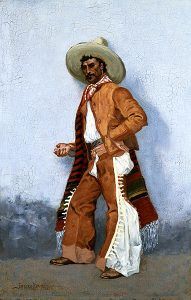

At the time of the acquisition of New Mexico by the United States, Espinosa, who was a Mexican owning vast herds of cattle and sheep, resided in his ancestral hacienda in a sort of barbaric luxury, with a host of semi-serfs known as Peons, to do his bidding, as did the other “Muy Ricos,” the ” Dons,” so-called, of his class of natives. These self-styled aristocrats of the wild country all boasted of their Castilian blue blood, claiming descent from the nobles of Cortez’ army, but the fact is, however, with rare exceptions, that their male ancestors, the rank, and file of that army, intermarried with the Aztec women, and they were really only a mixture of Indian and Spanish.

It so happened that Espinosa met an adventurous American, who, with hundreds of others, had been attached to the “Army of Occupation” in the Mexican War, or had emigrated from the States to seek their fortunes in the newly acquired and much over-rated territory. The Mexican Don and the American became fast friends, the latter making his home with his newly found acquaintance at the beautiful ranch in the mountains, where they played the role of a modern Damon and Pythias. With Don Espinosa lived his sister, a dark-eyed, bewitchingly beautiful girl about s17 years-old, with whom the susceptible American fell deeply in love, and his affection was reciprocated by the maiden, with a fervor of which only the women of the race from which she sprang are capable. The fascinating American had brought with him from his home in one of the New England States a large amount of money, for his parents were rich and spared no indulgence to their only son. He very soon unwisely made Espinosa his confidant and told him of his wealth. One night after the American had retired to his chamber, adjoining that of his host, he was surprised, shortly after he had gone to bed, by discovering a man standing over him, whose hand had already grasped the buckskin bag under his pillow which contained a considerable portion of his gold and silver. He sprang from his couch and fired his pistol randomly in the darkness at the would-be robber.

Felipe Espinosa

Espinosa, for it was he, was wounded slightly, and, being either enraged or frightened, he stabbed with his keen-pointed stiletto, which all Mexicans then carried, the young man whom he had invited to become his guest, and the blade entered the American’s heart, killing him instantly. The pistol-shot report awakened the other household members, who came rushing into the room just as the victim was breathing his last. Among them was the sister of the murderer, who, throwing herself on the body of her dead lover, poured forth the most bitter curses upon her brother. Espinosa realizing the terrible position in which he had placed himself, then and there determined to become an outlaw as he could frame no excuse for his wicked deed. Therefore, he hid at once in the mountains, carrying with him, of course, the sack containing the murdered American’s money.

Some time necessarily passed before he could get together a sufficient number of cut-throats and renegades from justice to enable him wholly to defy the authorities; but at last, he succeeded in rallying a strong force to his standard of blood and became the terror of the whole region, equaling in boldness and audacity the terrible Joaquin, of California notoriety in after years.

His headquarters were in the almost impregnable fastnesses of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, from which he made his invariably successful raids into the rich valleys below. There was nothing too bloody for him to shrink from; he robbed indiscriminately the overland coaches to Santa Fe, the freight caravans of the traders and government, the Mexicans’ ranches, or stole from the poorer classes without any compunction. He ran off horses, cattle, sheep— anything that he could utilize. If murder was necessary to the completion of his work, he never for a moment hesitated. Kidnapping, too, was a favorite pastime; but he rarely carried away to his rendezvous any other than the most beautiful of the New Mexican young girls, whom he held in his mountain den until they were ransomed or subjected to a fate more terrible.

In 1864 the bandit, after nearly ten years of unparalleled outlawry, was killed by Tobin. Tom had been on his trail for some time and at last tracked him to a temporary camp in the foothills, which he accidentally discovered in a grove of cottonwoods, by the smoke of the little camp-fire as it curled in light wreaths above the trees.

Tobin knew that there was but one of Espinosa’s followers with him at the time, as he had watched them both for some days, waiting for an opportunity to get the drop on them. To capture the pair of outlaws alive never entered his thoughts; he was as cautious as brave, and to get them dead was much safer and easier; so he crept up to the grove on his belly, Indian fashion, and lying behind the cover of a friendly log, waited until the noted desperado stood up when he pulled the trigger of his never-erring rifle, and Espinosa fell dead. A second shot quickly disposed of his companion, and the old trapper’s mission was accomplished.

To claim the reward offered by the authorities, Tom had to prove, beyond the possibility of doubt, that those whom he had killed were the dreaded bandit and one of his gang. He thought it best to cut off their heads, which he deliberately did, and packing them on his mule in a gunny-sack, he brought them into old Fort Massachusetts, afterward Fort Garland, Colorado, where they were speedily recognized; but whether Tom ever received the reward, I have my doubts, as he never claimed that he did. Tobin died in 1904, gray, grizzled, and venerable, his memory respected by all who had ever met him.

James Hobbs

Among all the men I have presented a hurried sketch, James Hobbs had perhaps a more varied experience than any of his colleagues. During his long life on the frontier, he was, in turn, a prisoner among the Indians and held for years by them; an excellent soldier in the war with Mexico; an efficient officer in the revolt against Maximilian when the attempt of Napoleon to establish an empire on this continent, with that unfortunate prince at its head, was defeated; an Indian fighter; a miner; a trapper; a trader, and a hunter.

Hobbs was born in the Shawnee nation, on the Big Blue River, about 23 miles from Independence, Missouri. His early childhood was entrusted to one of his father’s slaves. Reared on the eastern limit of the border, he very soon became familiar with the use of the rifle and shotgun; in fact, he was the principal provider of all the meat which the family consumed.

In 1835, when only 16 years old, he joined a fur-trading expedition under Charles Bent, destined for Bent’s Fort, Colorado, on the Santa Fe Trail over Pawnee Fork without special adventure, but there they had the usual tussle with the Indians, and Hobbs killed his first Indian. Two of the traders were pierced with arrows but not seriously hurt. The Pawnees — the tribe that had attacked the outfit — were driven away discomfited, not successfully stampeding a single animal.

When the party readied the Caches, on the Upper Arkansas River in Kansas, a smoke rising on the distant horizon, beyond the sandhills south of the river, made them proceed cautiously; for to the old plainsmen, that far-off wreath indicated either the presence of the Indians or a signal to others at a greater distance of the approach of the trappers.

The next morning, nothing had occurred to delay the march, buffalo began to appear, and Hobbs killed three of them. A cow, which he had wounded, ran across the Trail in front of the train, and Hobbs dashed after her, wounding her with his pistol, and then she started to swim the river. Hobbs, mad at the jeers which greeted him from the men at his missing the animal, started for the last wagon, in which was his rifle, determined to kill the brute that had enraged him. As he was riding along rapidly, Bent cried out to him, — “Don’t try to follow that cow; she is going straight for that smoke, and it means Injuns, and no good in ’em either.”

“But I’ll get her,” answered Hobbs, and he called to his closest comrade, John Baptiste, a boy of about his own age, to go and get his pack-mule and come along. “All right,” responded John, and together the two inexperienced youngsters crossed the river against the protests of the veteran leader of the party.

After a chase of about three miles, the boys came up with the cow, but she turned and showed fight. Finally, Hobbs, by riding around her, got in a good shot, which killed her. Jumping off their animals, both boys busied themselves to cut out the choice pieces for their supper, packed them on the mule, and started for the train. But it had suddenly become very dark, and they were in doubt about the direction of the Trail. Soon night came on so rapidly that neither could they see their own tracks by which they had come, nor the thin fringe of cottonwoods that lined the bank of the stream. Then they disagreed as to which was the right way. John succeeded in persuading Hobbs that he was correct, and the latter gave in, very much against his own belief on the subject.

They traveled all night and when morning came, were bewilderingly lost. Then Hobbs resolved to retrace the tracks by which, now that the sun was up, he saw that they had been going south, right away from the Arkansas River. Suddenly an immense herd of buffalo, containing at least two thousand, dashed by the boys, filling the air with the dust raised by their clattering hoofs, and right behind them rode a hundred Indians, shooting at the stampeded animals with their arrows.

“Get into that ravine !” shouted Hobbs to his companion. “Throw away that meat, and run for your life!”

It was too late; just as they arrived at the brink of the hollow, they looked back, and close behind them were a dozen Comanche.

The Indians rode up, and one of the party said in very good English, “How d’ do?”