Apache is a collective name given to several culturally related tribes that speak variations of the Athapascan language and are of the Southwest cultural area. The Apache separated from the Athapascan in western Canada centuries ago, migrating to the southwestern United States. Although there is some evidence Southern Athapascan peoples may have visited the Southwest as early as the 13th century AD, most scientists believe they arrived permanently only a few decades before the Spanish.

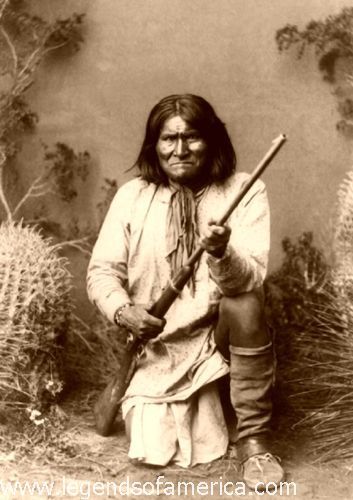

While living I want to live well.

— Geronimo

The Zuni, a Pueblo people, gave them the name Apachu, meaning “enemy.” In their dialects, the Apache call themselves Tinneh, Tinde, Dini, or one of several other variations, all meaning “the people.”

Early Apache were a nomadic people, ranging over a wide area of the United States, with the Mescalero Apache roaming as far south as Mexico. They were primarily hunter-gatherers, with some bands hunting buffalo and some practicing limited farming.

Men participated in hunting and raiding activities, while women gathered food, wood, and water. Western Apache tribes were matrilineal, tracing descent through the mother; other groups traced their descent through both parents. Polygamy was practiced when economic circumstances permitted, and marriage could be terminated easily by either party. Their dwellings were shelters of brush called wickiups, which were easily erected by the women and were well adapted to their arid environment and the constant shifting of the tribes. Some families lived in buffalo-hide teepees, especially among the Kiowa-Apache and Jicarilla. The Apache made little pottery and were known instead for their fine basketwork. In traditional Apache culture, each band consisted of extended families with a headman chosen for leadership abilities and exploits in war. For centuries they were fierce warriors, adept in wilderness survival, who carried out raids on those who encroached on their territory.

Religion was a fundamental part of Apache life. Their pantheon of supernatural beings included Ussen (or Yusn), the Giver of Life, and the ga’ns, or mountain spirits, who were represented in religious rites such as healing and puberty ceremonies. Men dressed elaborately to impersonate the ga’ns, wearing kilts, black masks, tall wooden-slat headdresses, body paint, and carrying wooden swords.

Trade was established between the long-established Pueblo peoples and the Southern Athabaskans by the mid-16th century, exchanging maize and woven goods for bison meat, hides, and material for stone tools.

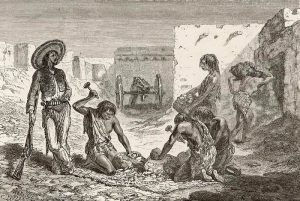

The Apache and the Pueblo managed to maintain generally peaceful relations; however, this changed with the appearance of the Spaniards. Arriving in the mid-1500s, the Spanish intruders drove northward into Apache territory, disrupting the Apache trade connections with neighboring tribes.

In April 1541, while traveling on the plains east of the Pueblo region, Francisco Coronado wrote:

“After seventeen days of travel, I came upon a rancheria of the Indians who follow these cattle [bison.] These natives are called Querechos. They do not cultivate the land but eat raw meat and drink the blood of the cattle they kill. They dress in the skins of the cattle, with which all the people in this land clothe themselves, and they have very well-constructed tents, made with tanned and greased cowhides, in which they live and which they take along as they follow the cattle. They have dogs which they load to carry their tents, poles, and belongings.”

When New Mexico became a Spanish colony in 1598, hostilities increased between the Spaniards and Apache. One source of the friction with the Spaniards was with the slave traders, who hunted down captives to serve as laborers in the silver mines of Chihuahua in northern Mexico. The Apache, in turn, raided Spanish settlements to seize cattle, horses, firearms, and captives of their own. Before long, the prowess of the Apache in battle became legend. The Apache were not so numerous at the beginning of the 17th century; however, their numbers were increased by captives from other tribes, particularly the Pueblo, Pima, Papago, other peaceful Indians, and white and Spanish peoples. Extending their depredations as far southward as Jalisco, Mexico, the Apache quickly became known for their warlike disposition.

An influx of Comanche into traditional Apache territory in the early 1700s forced the Lipan and other Apache to move south of their main food source, the buffalo. These displaced Apache then increased their raiding on the Pueblo Indians and non-Indian settlers for food and livestock.

Apache raids on settlers and migrants crossing their lands continued into the period of American westward expansion and the United States’ acquisition of New Mexico in 1848. Some Apache bands and the United States military authorities engaged in fierce wars until the Apache were pacified and moved to reservations.

The Mescalero were subdued by 1868, and a reservation was established for them in 1873. The Western Apache and their Yavapai allies were subdued in the U.S. military’s Tonto Basin Campaign of 1872-1873.

The Chiricahua Chief Cochise signed a treaty with the U.S. government in 1872 and moved with his band to an Apache reservation in Arizona. But Apache resistance continued under the Mimbreno Chief Victorio from 1877 to 1880.

The last band of Apache raiders, active in ensuing years under the Chiricahua Warrior Geronimo, was hunted down in 1886 and sent first to Florida, then to Alabama, and finally to the Oklahoma Territory, where they settled among the Kiowa-Apache.

The major Apache groups, each speaking a different dialect, include the Jicarilla and Mescalero of New Mexico, the Chiricahua of the Arizona-New Mexico border area, and the Western Apache of Arizona. The Yavapai-Apache Nation Reservation is southwest of Flagstaff, Arizona. Other groups were the Lipan Apache of southwestern Texas and the Plains Apache of Oklahoma.

The White Mountain Apache Tribe is located in the east-central region of Arizona, 194 miles northeast of Phoenix. This group manages the popular Sunrise Park Ski Resort and Fort Apache Timber Company. The Tonto Apache Reservation was created in 1972 near Payson in eastern Arizona. Within the Tonto National Forest, northeast of Phoenix, the reservation consists of 85 acres, serves about 100 tribal members, and operates a casino.

Noted leaders included Cochise, Mangas Coloradas, Chief Victorio, and Geronimo, who the U.S. Army found to be fierce warriors and skillful strategists.

Apache Bands:

Chiricahau:

The Chiricahua “great mountain” Apache were called such for their former mountain home in Southeast Arizona. They, however, called themselves Aiaha. The most warlike of the Arizona Indians, their raids extended into New Mexico, southern Arizona, and northern Sonora, Mexico. Some of their most noted leaders were Cochise, Victorio, Loco, Chato, Naiche, Bonito, Mangas Coloradas, and Geronimo.

The nomadic Chiricahua lived primarily in wickiups, with frame huts covered with matting, bark, and brush. When they moved on, they burned them. They were hunters and gatherers, surviving on berries, nuts, fruits, and game. They considered horse and mule flesh as delicacies. During the summer, they also did limited farming of corn and melon.

The Chiricahua formed clans, and chiefs were chosen for their ability and courage. However, there is evidence that chiefship was sometimes hereditary, as in the case of Cochise and his sons, Taza and Naiche.

In 1872 the Chiricahua were visited by a special commissioner, who concluded an agreement with Cochise, their chief, to cease hostilities and use his influence with the other Apache. By Fall, more than 1,000 of the tribe were settled on the newly established Chiricahua Reservation in southeast Arizona. Cochise died in 1874 and was succeeded as chief by his son Taza, who remained friendly to the Government. Still, the killing of some settlers who had sold whiskey to the Indians caused an intertribal broil, which, in connection with the proximity of the Chiricahua to the international boundary, resulted in abolishing the reservation against their will. The Camp Apache agency was established in 1872, and the year following, 1,675 Indians were placed there. But, in 1875, this agency was discontinued, and the Indians, much to their discontent, were transferred to San Carlos, where their enemies, the Yavapai, had also been removed.

The members of Geronimo’s band were the last to resist U.S. government control of the southwest. They finally surrendered in 1886 and were exiled to Florida, Alabama, and Oklahoma. The tribe was then released to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and the Mescalero Reservation in New Mexico, where most of the tribe live today.

Geronimo’s last stronghold was the Chiricahua Mountains in southeastern Arizona, part of which is now inside the Chiricahua National Monument.

Jicarilla:

The Jicarilla Apache were just one of six southern Athapascan groups that migrated out of Canada sometime around 1300 to 1500 A.D. Moving their way south; they settled in the southwest where their traditional homeland covered more than 50 million acres across northern New Mexico, southern Colorado and western Oklahoma.

The region’s geography shaped two bands of the Jicarilla – the Llaneros, or plains people, and the Olleros, or mountain-valley people. The name Jicarilla pronounced hek-a-REH-ya, means “little basket maker” in Spanish.

When Francisco Vásquez de Coronado’s expedition journeyed through the northeastern plains of New Mexico in search of gold, the Jicarilla lived a nomadic lifestyle and were generally indifferent to the intruders. That was until the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 triggered the re-conquest of New Mexico.

Before that time, there were approximately 10,000 Jicarilla Apache, but by 1897, their population had plummeted to just a little more than 300 souls, lost to disease, war, and famine.

In 1887, a reservation in northern New Mexico was established for the Jicarilla, who before that time were considered squatters on their own lands, denied citizenship and the right to own land.

Today, the Jicarilla Nation, of more than 3,000 members, is self-sufficient with a strong economy of sheep herding, oil and gas wells, and casinos. They continue to be acclaimed for the beauty and excellent craftsmanship of their traditional basket-making, beadwork, and clay pottery.

Mescalero:

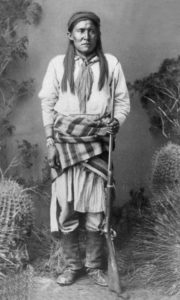

Mescalero Warriors, 1898

The Mescalero Apache were one of the fiercest of the Apache groups in the southwest when defending their homelands. Nomadic hunters and warriors moved from place to place, setting up their wickiups in Texas, Arizona, and Mexico. Between 1700 and 1750, the enemy Comanche displaced many Mescalero bands from the Southern Plains in northern and central Texas. At this time, they took refuge in the mountains of New Mexico, western Texas, Coahuila, and Chihuahua, Mexico.

A reservation was established for them in 1873, first located near Fort Stanton, New Mexico. Ten years later, another reservation was established, situated almost entirely in Otero County. Later, they opened their doors to other Apache bands, the Chiricahua, who were imprisoned at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and the Lipan Apache.

The tribe is federally recognized as the Mescalero Apache Tribe of the Mescalero Apache Reservation in south-central New Mexico. They are comprised of three sub-tribes — the Mescalero, Lipan, and Chiricahua, and have more than 3,000 members. Many live on the 720 square mile reservation that was once the heartland of their original territory.

Ranching and tourism are major sources of income.

In the 2000 U.S. census, about 57,000 people identified themselves as Apache only; an additional 40,000 people reported being part Apache. Many Apache live on reservations in Arizona and New Mexico. Farming, cattle herding, and tourist-related businesses are important economic activities. The modern Apache way of life combines traditional beliefs and rituals, such as mountain spirit dances and contemporary American culture.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2022.

Also See: