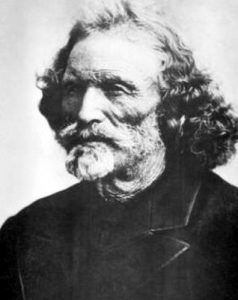

Jim Baker was another noted mountaineer and hunter of the same era as Kit Carson. He was born in Illinois and lived at home until he was 18, when he enlisted in the American Fur Company’s service, went immediately to the Rocky Mountains, and remained there until his death. According to the Indian custom, he married a wife from the Snake tribe, living with her relatives for many years and cultivating many of their habits, ideas, and superstitions. He firmly believed in the efficacy of the charms and incantations of the medicine men in curing diseases, divining where their enemy was to be found, forecasting the result of war expeditions, and other such ridiculous matters. Unfortunately, too. Baker sometimes took a little more whiskey than he could conveniently carry and often made a fool of himself, but he was a generous, noble-hearted fellow who would risk his life for a friend at any time or divide his last morsel of food.

Like mountaineers generally, Baker was liberal to a fault and eminently improvident. He made a fortune by his work, but at the annual rendezvous of the traders, at Bent’s Fort or the old Pueblo, he would throw away months’ earnings in a few days’ jollification.

He told General Marcy, who was a warm friend of his, that after one season in which he had been unusually successful in accumulating a large number of valuable furs, from the sale of which he had realized the handsome sum of $9,000 he resolved to abandon his mountain life, return to the settlements, buy a farm, and live comfortably during the remainder of his days. Accordingly, he was ready to leave and was on the eve of starting when a friend invited him to visit a monte-bank that had been organized at the rendezvous. He was easily led away, determined to take a little social amusement with his old comrade, whom he might never see again, and followed him; the result of which was that the whiskey circulated freely, and the next morning found Baker without a cent of money; he had lost everything. Thus, his entire plans were frustrated, and he returned to the mountains, hunting with the Indians until he died.

Jim Baker’s opinions of the wild Indians of the Great Plains and the mountains were very decided: “That they are the most onsartinist varmints in all creation, an’ I reckon thar not more’n half-human; for you never seed a human, arter you’d fed an’ treated him to the best fixin’s in your lodge, jis turn round and steal all your horses, or ary other thing he could lay his hands on. No, not adzactly. He would feel kind o’ grateful and ask you to spread a blanket in his lodge ef you ever came his way. But the Injin don’t care shucks for you, and is ready to do you a lot of mischief as soon as he quits your feed. No, Cap.,” he said to Marcy when relating this, “it’s not the right way to make ’em gifts to buy a peace; but ef I war gov’nor of these United States, I’ll tell what I’d do. I’d invite ’em all to a big feast, and make ’em think I wanted to have a talk; and as soon as I got ’em together, I’d light in and raise the har of half of ’em, and then t’other half would be mighty glad to make terms that would stick. That’s the way I’d make a treaty with the dog’oned red-bellied varmints, and as sure as you’re born, Cap., that’s the only way.”

When he first met Baker, the general asked if he had traveled much over the United States settlements before he came to the mountains, to which he said: “Right smart, right smart, Cap.” He then asked whether he had visited New York or New Orleans. “No, I hasn’t, Cap., but I’ll tell you whar I have been. I’ve been mighty nigh all over four counties in the State of Illinois!”

He was very fond of his Indian wife and children and usually treated them kindly; only when he was in liquor did he maltreat them.

Once, he came over to New Mexico, where General Marcy was stationed at the time, and determined that for the time being, he would cast aside his leggings, moccasins, and other mountain dress and wear a civilized wardrobe. Accordingly, he fitted himself out with one. When Marcy met him shortly after he had donned the strange clothes, he had undergone such an entire change that the general remarked he should hardly have known him. He did not take kindly to this and said: “Consarn these store boots, Cap.; they choke my feet like h—l.” It was the first time in 20 years that he had worn anything on his feet, but moccasins and they were not ready for the torture inflicted by breaking in a new pair of absurdly fitting boots. He soon threw them away and resumed the softer foot-gear of the mountains.

Baker was a famous bear hunter and had been at the death of many a grizzly. On one occasion, he set his traps with a comrade on the Arkansas River’s headwaters when they suddenly met two young grizzly bears about the size of full-grown dogs. Baker remarked to his friend that if they could “light in and kill the varmints ” with their knives, it would be a big thing to boast of. They both accordingly laid aside their rifles and “lit in,” Baker attacking one and his comrade the other. The bears immediately raised themselves on their haunches and were ready for the encounter. Baker ran around, endeavoring to get in a blow from behind with his long knife, but the young brute he had tackled was too quick for him and turned as he went around so, as always, to confront him face to face. He knew if he came within reach of his claws, although young, he could inflict a formidable wound; moreover, he feared that the howls of the cubs would bring the infuriated mother to their rescue when the hunters’ chances of getting away would be slim. These thoughts floated hurriedly through his mind and made him desirous to end the fight as soon as possible. He made many vicious lunges at the bear, but the animal invariably warded them off with his strong forelegs like a boxer. However, this tactic cost the lively beast several severe cuts on his shoulders, making him more furious. At length, he took the offensive and with his mouth frothing with rage, bounded toward Baker, who caught and wrestled with him, succeeding in giving him a death wound under the ribs.

While all this was going on, his comrade had been furiously engaged with the other bear and, by this time, had become greatly exhausted, with the odds decidedly against him. He entreated Baker to come to his assistance at once, which he did, but much to his astonishment, as soon as he entered the second contest, his comrade ran off, leaving him to fight the battle alone. He was, however, again victorious and soon had the satisfaction of seeing his two antagonists stretched out in front of him. Still, as he expressed it, ” I made my mind up I’d never fight nary nother grizzly without a good shootin’-iron in my paws.”

He established a little store at the crossing of Green River and had for some time been doing a fair business in trafficking with the emigrants and trading with the Indians; but shortly a Frenchman came to the same locality and set up a rival establishment, which, of course, divided the limited trade, and naturally reduced the income of Baker’s business.

This engendered a bitter feeling of hostility, which soon culminated in a cessation of all social intercourse between them. About this time, General Marcy arrived there on his way to California, and he described the situation of affairs:

“I found Baker standing in his door, with a revolver loaded and cocked in each hand, very drunk and immensely excited. I dismounted and asked him the cause of all this disturbance. He answered: ‘That thar yaller-bellied, toad-eatin’ Parly Voo, over thar, an’ me, we’ve been havin’ a small chance of a scrimmage today. The sneakin’ polecat, I’ll raise his har yet, ef he don’t quit these diggins’!’

“It seems that they had an altercation in the morning, which ended in a challenge when they ran to their cabins, seized their revolvers, and fired from the doors, which were only about a hundred yards from each other. They then retired to their cabins, drank whiskey, reloaded their revolvers, and renewed the combat again. This strange duel had been going on for several hours when I arrived, but, fortunately for them, the whiskey had such an effect on their nerves that their aim was very unsteady, and none of the shots had as yet taken effect.

“I took away Baker’s revolvers, telling him how ashamed I was to find a man of his usual good sense making such a fool of himself. He gave in quietly, saying he knew I was his friend but did not think I would wish to have him take insults from a cowardly Frenchman.

“The following morning at daylight, Jim called at my tent to bid me goodbye and seemed very sorry for what had occurred the day before. He stated that this was the first time since his return from New Mexico that he had allowed himself to drink whiskey, and when the whiskey was in him, he had ‘nary sense.”

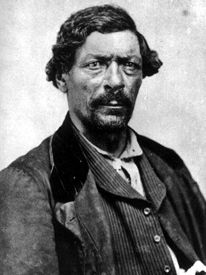

James Pierson Beckwourth

Among the many men who have distinguished themselves as mountaineers, traders, and Indian fighters along the Santa Fe Trail line was one who eventually became the head chief of one of the most numerous and valorous tribes of North American Indians, James P. Beckwourth. Estimates of him vary considerably. Francis Parkman, the historian, who I think never saw him and writes merely from hearsay, says: “He is a ruffian of the worst class; bloody and treacherous, without honor or honesty; such, at least, is the character he bears on the Great Plains. Yet in his case, the standard rules of character fail; for though he will stab a man in his slumber, he will also do the most desperate and daring acts.”

I never saw Beckwourth, but I have heard of him from my mountaineer friends who knew him intimately; I think he died long before Parkman made his tour to the Rocky Mountains. Colonel Daniel Boone, the Bents, Kit Carson, Lucien Maxwell, and others ascribed to him no such traits as those given by Parkman. As to his honesty, it is unquestioned that Beckwourth was the most honest trader among the Indians who were then engaged in the business. Kit Carson and Colonel Boone were the only Indian agents I ever knew or heard of that dealt honestly with the various tribes, as they were always ready to acknowledge. The withdrawal of the former by the government was the cause of a great war, so Beckwourth was an honest Indian trader.

He was a born leader of men and was known from the Yellowstone to the Rio Grande, from Santa Fe to Independence, and in St. Louis, Missouri. He ran away from the latter town when a boy with a party of trappers and himself became one of the most successful of that hardy class. The woman who bore him had played in her childhood beneath the palm trees of Africa; his father was a native of France and went to the banks of the wild Mississippi River of his own free will, but probably also from reasons of political interest to his government.

In person, Beckwourth was of medium height and great muscular power, quick of apprehension, and with the courage of the highest order. Probably no man ever met with more personal adventures involving danger to life, even among the mountaineers and trappers who, early in the century, faced the perils of the remote frontier. He always wore suspended a perforated bullet from his neck, with a large oblong bead on each side of it, tied in place by a single thread of sinew. This amulet he obtained while chief of the Crows, and it was his “medicine,” with which he excited his warriors’ superstition.

His success as a trader among the various tribes of Indians has never been surpassed, for his close intimacy with them made him know what would best please their taste. They bought of him when other traders stood idly at their stockades, waiting almost hopelessly for customers.

But Beckwourth himself said: “The traffic in whiskey for Indian property was one of the most infernal practices ever entered into by man. Let the most casual thinker sit down and figure up the profits on a forty-gallon cask of alcohol, and he will be thunderstruck, or rather whiskey-struck. When it was to be disposed of, four gallons of water were added to each gallon of alcohol. In two hundred gallons, there are 1600 pints, for each one of which the trader got a buffalo robe worth five dollars. The Indian women toiled many long weeks to dress those sixteen hundred robes. The white traders got them for worse than nothing, for the poor Indian mother hid herself and her children until the effect of the poison passed away from the husband and father, who loved them when he had no whiskey and abused and killed them when he had. Six thousand dollars for sixty gallons of alcohol! Is it a wonder with such profits that men got rich who were engaged in the fur trade? Or was it a miracle that the buffalo were gradually exterminated? — killed with so little remorse that the hides, among the Indians themselves, were known by the appellation of ‘A pint of whiskey.'”

Beckwourth claims to have established the Pueblo, where the beautiful city of Pueblo, Colorado, is now situated. He says: “On the 1st of October, 1842, on the Upper Arkansas River, I erected a trading post and opened a successful business. I was joined by 15 to 20 free trappers with their families in a very short time. We all united our labor and constructed an adobe fort 60 yards square. By the following spring, it had grown into quite a little settlement, and we called it Pueblo.”

Immediately after Kit Carson, the second wreath of pioneer laurels for bravery and prowess as an Indian fighter, and trapper, must be conceded to Richens Lacy Wootton, known first as “Dick” in his younger days on the plains, then, when age had overtaken him, as “Uncle Dick.” His father was born in Virginia when he was seven years of age and removed with his family to Kentucky, where he cultivated a tobacco plantation. Like his predecessor and lifelong friend Carson, young Wootton tired of the monotony of farming and, in the summer of 1836, made a trip to the busy frontier town of Independence, Missouri, where he found a caravan belonging to Colonel St. Vrain and the Bents, already loaded, and ready to pull out for the fort built by the latter, and named for them.

Wootton had a fair business education and was superior in this respect to his companions in the caravan to which he had attached himself. It was by those rough but kindhearted men that he was called “Dick,” as they could not readily master the more complicated name of ” Richens.”

When he started from Independence on his initial trip across the plains, he was only 19 years old, but, like all Kentuckians, perfectly familiar with a rifle and could shoot out a squirrel’s eye with the certainty which long practice and hardened nerves assure.

The caravan, in which he was employed as a teamster, was composed of only seven wagons; but a larger one, of which were more than 50, had preceded it, and as that was heavily laden, and the smaller one only lightly, it was intended to overtake the former before the dangerous portions of the Santa Fe Trail were reached, which it did in a few days and was assigned a place in the long line.

Every man had to take his turn in standing guard, and the first night that it fell to young Wootton was at Little Cow Creek in the Upper Arkansas River Valley. Thus far, nothing had occurred during the trip to imperil the caravan’s safety, nor was any attack by the Indians looked for.

Wootton’s post comprehended the whole length of one side of the corral, and his instructions were to shoot anything he saw moving outside the line of mules farthest from the wagons. The young sentry was very vigilant. He did not feel sleepy but eagerly watched for something that might come within the prescribed distance, though not expecting such a contingency.

About two o’clock, he heard a slight noise and saw something moving about, some 60-70 yards from where he was lying on the ground, to which he had dropped the moment the strange sound reached his ears. Of course, his first thoughts were of Indians, and the more he peered through the darkness at the slowly moving object, the more convinced he was that it must be a blood-thirsty warrior.

He rose to his feet and blazed away, the shot rousing everybody, and all came rushing with their guns to learn what the matter was.

Wootton told the wagon master that he had seen what he supposed was an Indian trying to slip up to the mules and that he had killed him. Some men crept very circumspectly to the spot where the supposed dead Indian was lying while young Wootton remained at his post, eagerly waiting for their report. Presently he heard a voice cry out: “I’ll be d—d ef he hain’t killed ‘Old Jack!”‘ “Old Jack” was one of the lead mules of one of the wagons. He had torn up his picket pin and strayed outside of the lines, resulting in the faithful brute meeting his death at the hands of the sentry. Wootton declared that he was not to be blamed, for the animal had disobeyed orders while he had strictly observed them!

At Pawnee Fork, a few days later, the caravan had a genuine tussle with the Comanche. It was a bright moonlight night, and about 200 mounted Indians attacked them. It was rare for Indians to begin a raid after dark, but they swept down on the unsuspecting teamsters, yelling like a host of demons. They were generally armed with bows and arrows, though a few had fusees (a fire-lock musket with an immense bore).

Although they were not expected, they received a warm greeting, the guard noticing the Indians in time to prevent a stampede of the animals, which evidently was the sole purpose for which they came, as they did not attempt to break through the corral to get at the wagons. It was the mules they were after. They charged among the men, vainly endeavoring to frighten the animals and make them break loose, discharging showers of arrows as they rode by. However, the camp was too hot for them, defended by old teamsters who had made the dangerous passage of the plains many times before and were up to all the Indian tactics. They failed to get a single mule but paid for their temerity by leaving three of their party dead, just where they had been tumbled off their horses, not even having time to carry the bodies off, as they usually do. Kit Carson, ten years before, when on his first journey and met with the same adventure while on post at Pawnee Rock, Kansas.

Wootton passed sometime during the early days of his career at Bent’s Fort, Colorado, in 1836-37. He was a great favorite with both of the proprietors and with them, went to several Indian villages, where he learned the art of trading with the Indians.

The winters of the years mentioned were noted for the Pawnee’s incursions into the region of the fort. They always pretended friendship for the whites when any of them were inside of its sacred precincts, but their whole manner changed when they, by some stroke of fortune, caught a trapper or hunter alone on the prairie or in the foothills; he was a dead man sure, and his scalp was soon dangling at the belt of his cowardly assassins. Hardly a day passed without witnessing some poor fellow running for the fort with a band of the red devils after him; frequently, he escaped the keen edge of their scalping knife, but every once in a while, a man was killed. At one time, two herders with their animals within 50 yards of the fort, going out to the grazing ground, were killed, and every hoof of stock runoff.

A party from the fort, comprising only eight men, among whom was young Wootton, made up for lost time with the Indians at the crossing of Pawnee Fork, the same place where he had had his first fight. The men had set out from the fort to meet a small caravan of wagons from the East, loaded with supplies for Bent’s Fort. It happened that a band of 16 Pawnee warriors were watching for the arrival of the train, too. Wootton’s party was well mounted while the Pawnee were on foot, and although the Indians were two to one, the advantage was decidedly in favor of the whites.

The Indians were armed with bows and arrows only, and while it was an easy matter for the whites to keep out of the way of the shower of missiles that the Indians commenced hurling at them, the latter became easy prey to the unerring rifles of their assailants, who killed 13 out of the 16 in a very short time. The remaining three took leave of their comrades at the beginning of the conflict and, abandoning their arms, rushed up to the caravan, which was appearing over a small divide, and gave themselves up. The Indian custom was observed in their case, although rarely were any prisoners taken in these conflicts on the Santa Fe Trail. Another curious custom was also followed. When the party encamped, they were well fed and the next morning supplied with rations enough to last them until they could reach one of their villages and sent off to tell their head chief what had become of the rest of his warriors.

As he expected, the Ute followed on his trail and came up with his little party on a prairie where there was no chance to ambush or hide. They had to fight because they could not help it, but resolved to sell their lives as dearly as possible, as the Ute outnumbered them twenty to one; Wootton having only eight men with him, including the Shawnee.

The pack animals, of which they had a great many, loaded with the goods intended for the Indians, were corralled in a circle, inside of which the men hurried and awaited the first assault of the foe. In a few moments, the Ute began to circle the trappers and open fire. The trappers promptly responded and made every shot count, for all of the men, not even excepting the Shawnee, were experts with the rifle. They did not mind the arrows which the Ute showered upon them, as few, if any, reached where they stood. The Indians had a few guns, but they were of the poorest quality, and they did not know how to handle them then as they learned to do later, so their bullets were almost as harmless as their arrows.

The trappers made terrible havoc among the Ute’ horses, killing so many of them that the Indians, in despair, abandoned the fight and allowed Wootton and his men to get away, which they did as rapidly as possible.