When the train camped for the night, the wagons were corralled, and the men and mules were brought inside the circle. The grass was cut with sheath knives and fed to the animals instead of being picketed out as usual, and as large a guard as possible was detailed. When the camp had settled down to perfect quiet, Carson crawled outside it, taking with him a Mexican boy and, after explaining the danger which threatened them all, told him that it was in his power to save the lives of the company. Then he sent him on alone to Rayado, New Mexico, a journey of nearly 300 miles, to ask for an escort of United States troops to be sent out to meet the train, impressing upon the brave little Mexican the importance of putting a good many miles between himself and the camp before morning. And so he started him, with a few rations of food, without letting the rest of his party know that such measures were necessary. The boy had been in Carson’s service for some time and was known to him as a faithful and active messenger, and in a wild country like New Mexico, with its people’s outdoor life and habits, such a journey was not unusual.

Carson returned to the camp to watch himself all night; at daybreak, all were on the Santa Fe Trail again. No Indians appeared until nearly noon when five warriors came galloping up toward the train. As soon as they came close enough to hear his voice, Carson ordered them to halt and, going up to them, told how he had sent a messenger to Rayado the night before to inform the troops that their tribe was annoying him and that if he or his men were molested, terrible punishment would be inflicted by those who would surely come to his relief. The Indians replied that they would look for the moccasin tracks, which they undoubtedly found. The whole village passed away toward the hills after a little while, evidently seeking a place of safety from an expected attack by the troops.

The young Mexican overtook the detachment of soldiers whose officer had caused all the trouble with the Indians, to whom he told his story, but failing to secure any sympathy, he continued his journey to Rayado and procured from the garrison of that place immediate assistance. Major Grier, commanding the post, at once dispatched a troop of his regiment, which, by forced marches, met Carson 25 miles below Bent’s Fort. Though it encountered no Indians, the rapid movement had a good effect on the Indians, impressing them with the power and promptness of the government.

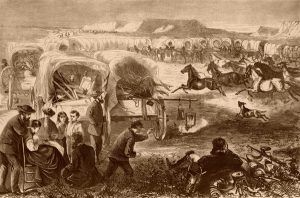

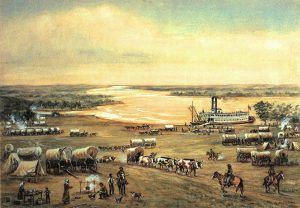

Early in the spring of 1865, Carson was ordered, with three companies, to stop the depredations of marauding bands of Comanche upon the caravans and emigrant outfits traveling the Santa Fe Trail. He left Fort Union for the Arkansas River to establish a fortified camp at Cedar Bluffs, or Cold Spring, to afford a refuge for the freight trains on that dangerous part of the Trail. The Indians had been harassing not only the caravans of the citizen traders but also those of the government, which carried supplies to the several military posts in the Territory of New Mexico. Therefore, an expedition was planned by Carson to punish them, and he soon found an opportunity to strike a blow near the adobe fort on the Canadian River. His force consisted of the First Regiment of New Mexican Volunteer Cavalry and 75 friendly Indians, his entire command numbering 14 commissioned officers and 396 enlisted men. With these, he attacked the Kiowa village, consisting of about 150 lodges. The fight was very severe and lasted from half-past eight in the morning until sundown. The Indians, with more than ordinary intrepidity and boldness, made repeated stands against the fierce onslaughts of Carson’s cavalrymen but were at last forced to give way and were cut down as they stubbornly retreated, suffering a loss of some 60 killed and wounded. In this battle, only two privates and one noncommissioned officer were killed, and one non-commissioned officer and thirteen privates, four of whom were friendly Indians, were wounded. The command destroyed 150 lodges, a large amount of dried meats, berries, buffalo robes, cooking utensils, and a buggy and spring wagon, the property of Sierrito, the Kiowa chief.

In his official account of the fight, Carson stated that he found ammunition in the village, which had been furnished, no doubt, by unscrupulous Mexican traders.

He told me that he never was deceived by Indian tactics but once in his life. He said that he was hunting with six others after buffalo in the summer of 1835; they had been successful and came into their little bivouac one night very tired, intending to start for the rendezvous at Bent’s Fort the next morning. They had several dogs, among them some excellent animals. These barked a good deal and seemed restless, and the men heard wolves.

“I saw,” said Kit, “two big wolves sneaking about, one of them quite close to us. Gordon, one of my men, wanted to fire his rifle at it, but I did not let him for fear he would hit a dog. I admit that I had a sort of an idea that those wolves might be Indians; but when I noticed one of them turn short around and heard the clashing of his teeth as he rushed at one of the dogs, I felt easy then and was certain that they were wolves sure enough. But the red devil fooled me, for he had two dried buffalo bones in his hands under the wolf skin, and he rattled them together every time he turned to make a dash at the dogs! Well, by and by, we all dozed off, and it wasn’t long before a noise, and a big blaze suddenly aroused me. I rushed out the first thing for our mules and held them. If the Indians had been smart, they could have killed us in a trice, but they ran as soon as they fired at us. They killed one of my men, putting five bullets in his body and eight in his buffalo robe. The Indians were a band of Sioux on the war trail after a band of Snakes found us by sheer accident. They endeavored to ambush us the next morning, but we got wind of their little game and killed three of them, including the chief.”

Carson’s nature was made up of some very noble attributes. He was brave but not reckless like George Custer, a veritable exponent of Christian altruism and as true to his friends as the needle to the pole. Under the average stature and rather delicate-looking in his physical proportions, he was nevertheless a quick, wiry man with nerves of steel and possessing an indomitable will. He was full of caution but showed a coolness in the moment of supreme danger that was good to witness.

During a short visit at Fort Lyon, Colorado, where a favorite son of his was living, early in the morning of May 23, 1868, while mounting his horse in front of his quarters (he was still fond of riding), an artery in his neck was suddenly ruptured, from the effects of which, notwithstanding the medical assistance rendered by the fort surgeons, he died in a few moments.

After reposing for some time at Fort Lyon, his remains were taken to Taos, his home in New Mexico, where an appropriate monument was erected over them. In the Plaza at Santa Fe, his name also appears cut on a cenotaph raised to commemorate the services of the soldiers of the Territory. As an Indian fighter, he was matchless. The identical rifle he used for more than 35 years, which never failed him, he bequeathed, just before his death, to Montezuma Lodge, A. F. & A. M., Santa Fe, of which he was a member.

James Bridger, ” Major Bridger,” or ” Old Jim Bridger,” as he was called, another famous coterie of pioneer frontiersmen, was born in Washington, DC, in 1807. When very young, a mere boy, he joined the great trapping expedition under the leadership of James Ashley and, with it, traveled to the far West, remote from the extreme limit of border civilization, where he became the compeer and comrade of Kit Carson, and certainly the foremost mountaineer, strictly speaking, the United States has produced.

Having left behind him all possibilities of education at such an early age, he was illiterate in his speech and as ignorant of the conventionalities of polite society as an Indian; but he possessed a heart overflowing with the milk of human kindness, was generous in the extreme, and honest and true as daylight.

He was especially distinguished for discovering a defile through the intricate mazes of the Rocky Mountains, which bears his name, Bridger’s Pass in Wyoming. He rendered important services as a guide and scout during the early preliminary surveys for a transcontinental railroad. For a series of years, he was in the government’s employ, in the old regular army on the Great Plains and the mountains, long before the breaking out of the Civil War. To Bridger also belongs the honor of having seen, first of all, white men, the Great Salt Lake of Utah in the winter of 1824-25.

After a series of adventures, hairbreadth escapes, and terrible encounters with the Indians, in 1856, he purchased a farm near Westport, Missouri [Kansas City]; but soon left it in his hunger for the mountains, to return to it only when worn-out and blind, to be buried there without even the rudest tablet to mark the spot.

“I would rather sleep in the southern corner of a little country churchyard than in the tomb of the Capulets.” This quotation came to my mind one Sunday morning two or three years ago as I mused over Bridger’s neglected grave among the low hills beyond the quaint old town of Westport [Kansas City], Missouri. I thought I knew, as I stood there, that he whose bones were moldering beneath the blossoming clover at my feet would have wished for his last couch a more perfect solitude and isolation from the wearisome world’s busy sound than even the immortal Burke.

The grassy mound, over which there was no stone to record the name of its occupant, covered the remains of the last of his class, a type that vanished forever, for the border is a thing of the past; and upon the gentle breeze of that delightful morning, like the droning of bees in a full-flowered orchard, was wafted to my ears the hum of Kansas City’s civilization, only three or four miles distant, in all of which I was sure there was nothing that would have been congenial to the old frontiersman.

At one time early in the 1860s, while the engineers of the proposed Union Pacific Railroad were temporarily in Denver, Colorado, then an insignificant mushroom hamlet, they became somewhat confused about the most practicable point in the range over which to run their line. After debating the question, they determined, upon a suggestion from some of the old settlers, to send for Jim Bridger, who was then visiting in St. Louis, Missouri. A pass via the overland stage was enclosed in a letter to him, and he was urged to start for Denver at once, though nothing of the business for which his presence was required was told him in the text.

In about two weeks, the old man arrived, and the next morning, after he had rested, asked why he had been sent for from such a distance.

The engineers then began to explain their dilemma. The old mountaineer waited patiently until they had finished, when, with a look of disgust on his withered countenance, he demanded a large piece of paper, remarking at the same time, — “I coulda told you fellers all that in St. Louis, and saved you the expense of bringing me out here.”

He was handed a sheet of manila paper used for drawing the details of bridge plans. The veteran pathfinder spread it on the ground before him, took dead coal from the ashes of the fire, drew a rough outline map, and, pointing to a certain peak just visible on the serrated horizon, said: “There’s where you fellers can cross with your road, and nowhere else, without more diggin’ an’ cuttin’ than you can think of.”

That crude map is preserved, I have been told, in the great corporation’s archives, and its line crosses the prominent spurs of the Rocky Mountains, just where Bridger said it could with the least work.

The resemblance of old John Simpson Smith, another of the coterie, to President Andrew Johnson was absolutely astonishing. When that chief magistrate, in his “swinging around the circle,” had arrived at St. Louis and was riding through the streets of that city in an open barouche, he was pointed out to Jim Bridger, who happened to be there. But, the venerable guide and scout, with supreme disgust depicted on his countenance at the idea of anyone attempting to deceive him, said to his informant, — “H—l! Bill, you can’t fool me! That’s old John Smith.”

Many years ago, during Bridger’s first visit to St. Louis, Missouri, then a relatively small place, a friend accidentally came across him sitting on a dry-goods box in one of the narrow streets, evidently disgusted with his situation. To the inquiry about what he was doing there all alone, the old man replied, — “I’ve been settin’ in this infernal canon ever since mornin’, waitin’ for someone to come along an’ invite me to take a drink. Hundreds of fellers have passed both ways, but none of ’em has opened his head. I never seen sich an unsociable crowd!”

Bridger had a fund of most remarkable stories, which he had drawn upon so often that he really believed them to be true.

General Gatlin, who graduated from West Point in the early 1830s, and commanded Fort Gibson in the Cherokee Nation over 60 years ago, told me that he remembered Bridger very well; and had once asked the old guide whether he had ever been in the great canyon of the Colorado River.

“Yes, sir,” replied the mountaineer, “I have many times. There’s where the oranges and lemons bear all the time, and the only place I was ever at where the moon’s always full!”

He told me and also many others, at various times, that in the winter of 1830, it began to snow in the valley of the Great Salt Lake and continued for 70 days without cessation. The whole country was covered to a depth of seventy feet, and all the vast herds of buffalo were caught in the storm and died, but their carcasses were perfectly preserved.

“When spring came, all I had to do,” declared he, “was to tumble ’em into Salt Lake, an’ I had pickled buffalo enough for myself and the whole Ute Nation for years!”

He said that there had been no buffalo in that region because of that terrible storm, which annihilated them.

Bridger had been the guide, interpreter, and companion of that distinguished Irish sportsman, Sir George Gore. His strange tastes led him in 1855 to abandon life in Europe and bury himself for over two years among the Indians in the wildest and most unfrequented glens of the Rocky Mountains.

The outfit and adventures of this titled Nimrod, conducted as they were on the largest scale, exceeded anything of the kind ever before seen on this continent, and the results of his wanderings will compare favorably with those of Gordon Cumming in Africa.

Some idea may be formed of his outfit’s magnitude when it is stated that his retinue consisted of about fifty individuals, including secretaries, stewards, cooks, flymakers, dog-tenders, servants, etc. He was carried over the country with a train of 30 wagons, alongside numerous saddle horses and dogs.

During his lengthened hunt, he killed the enormous aggregate of forty grizzly bears and twenty-five hundred buffalo, besides numerous antelope and other small game.

Bridger said of Sir George that he was a bold, dashing, successful hunter and an agreeable gentleman. His habit was to lie in bed until about ten or eleven o’clock in the morning. He took a bath, ate his breakfast, and set out, generally alone, for the day’s hunt, and it was not unusual for him to remain out until ten at night, seldom returning to the tents without augmenting the catalog of his beasts. His dinner was served, and he generally extended an invitation to Bridger. After the meal was over and a few glasses of wine had been drunk, he was in the habit of reading from some book and eliciting from Bridger his comments thereon. His favorite author was Shakespeare, which Bridger “reckin’d was too highfalutin” for him; moreover, he remarked, “thet he rather calcerlated that thar big Dutchman, Mr. Full-stuff, was a leetle too fond of lager beer,” and thought it would have been better for the old man if he had “stuck to Bourbon whiskey straight.”

Bridger seemed very much interested in the adventures of Baron Munchausen but admitted after Sir George had finished reading them that “he be dog’oned ef he swallered everything that thar Baron Munchausen said,” and thought he was “a darned liar,” yet he acknowledged that some of his own adventures among the Blackfeet would be equally marvelous “if writ down in a book.”

A man whose one act had made him awe-inspiring was Belzy Dodd. Uncle Dick Wootton, in relating the story, says: “I don’t know what his first name was, but Belzy was what we called him. His head was as bald as a billiard ball, and he wore a wig. One day while we were all at Bent’s Fort, while there were many Indians about, Belzy concluded to have a bit of fun. He walked around, eying the Indians fiercely for some time, and finally, dashing in among them, he gave a series of war-whoops which discounted a Comanche yell, and pulling off his wig, threw it down at the feet of the astonished and terror-stricken red men.

The Indians thought the fellow had jerked off his own scalp, and not one of them wanted to stay and see what would happen next. They left the fort, running like so many scared jack-rabbits, and after that none of them could be induced to approach anywhere near Dodd.”

They called him “The-white-man-who-scalps-himself,” and Uncle Dick said that he believed he could have traveled across the plains alone with perfect safety.