By Randall Parrish in 1907

From a purely technical viewpoint, the Plains formed only a comparatively small portion of that extensive area of prairie country of the Midwest. However, in history, the term has become quite generally applied as descriptive of all that vast region of grassland and arid desert that extended like an uncharted sea of green and brown desolation between the Missouri River valley upon the northeast and the foothills of the Rocky Mountains.

This truly immense territory, extending from about the center of the Dakotas southward to the Rio Grande, possessed an average width of 500 miles. It embraced Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, and the larger part of North Dakota and South Dakota, together with a considerable portion of New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming.

While broadly similar in topography, it was nevertheless varied by numerous river courses, the outcropping of low mountains, shifting sand hills, occasional strips of woodland, and the gradual divergence from rolling, luxuriant prairie to level, barren plain. However, there remained a peculiar sameness from which there was no escape. Mile after mile revealed the same vast picture of solitude, haunting in its loneliness, baffling in its similarity of outline.

Description of the Surface

Along the rivers — usually shallow streams, the water was often red and the bottoms treacherous with quicksand. There were commonly miles of rough, broken land, frequently terminating in high bluffs, and these occasionally traversed by ravines of considerable depth and abruptness. Growing sparsely and deformed by wind, trees clung precariously to these steep hillsides, while cottonwoods and willows fringed the banks of smaller streams, usually visible for long distances. There were considerable areas of sand, constantly shifting before the violence of storms, the mounds assuming grotesque shapes, and were usually destitute of water and vegetation. Patches of alkali, white and poisonous, stared forth from the surrounding green, rendering the streams salty and not drinkable for man or beast. To the north and south of the Black Hills, the Wichita Buttes and the Washita Range rose from the very heart of the surrounding desolation, tree-covered and rocky. Here and there, “badlands,” ugly and drear, gave unpleasant variety. In widely remote regions, odd growths of black-jack extended for leagues, sometimes nearly impenetrable, so closely interlaced were the trees, while toward the more western mountain boundary, vast canyons formed almost impassable barriers, and isolated buttes arose like ghosts from out of the enveloping plain, assuming fantastic shapes under the relentless chisel of the elements.

A remarkable region was found in the sandhills of what is now Nebraska. These, rounded and possessing a thin covering of turf, often of considerable height, are so precisely like each other that it is almost impossible to distinguish between them. They afford no guidance but rather produce the confusing and baffling effect of a maze, and once off the trail, the unfortunate traveler sometimes becomes wholly lost. Further north, between the Black Hills and the Missouri River, lies the Mauvaises Terres, or White River Badlands of Nebraska. Here, Nature seems to have exerted herself searching for the repulsive. The whole country is a series of gullies, with hills rising above them carved by the elements into the most fantastic forms, unlike anything to be found elsewhere. The soil appears oily, becoming so slippery when wet that climbing the steep slopes is almost impossible. On these barren, ash-colored hills, scarcely the slightest vegetation thrives. Other than the snake and the lizard, little animal life is to be found, extending a scene of complete desolation.

Yet, considered as a whole, and as the earlier travelers certainly perceived it, this area was composed of irregular, rolling prairie, bearing the appearance of innumerable petrified waves ever-extending toward the western horizon until growing continually less and less pronounced, they finally settled down into vast level stretches, forming the Plains proper bordering the Rockies. Although usually imperceptible to the eye throughout this distance, the earth’s surface steadily increased. The land became more arid, the rainfall perceptibly less, the waters of the rivers diminished in volume, the atmosphere grew lighter, and the luxuriant herbage of the Eastern prairies changed into the short, nutritious buffalo grass of the Western plateaus. All tree growth completely disappeared, nothing remaining to break the drear desolation except the ghostly cactus, or the diminutive Spanish bayonet, with here and there, a naked sage bush, the grim flower of the desert.

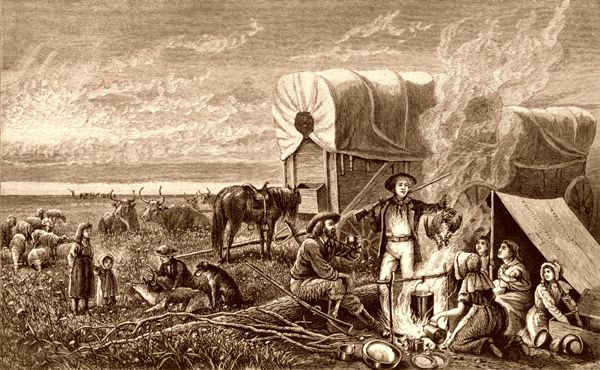

Three Distinct Belts to be Crossed

To the traveler advancing due west from the Missouri River, there were three distinct belts, averaging about 150 miles each, through which a slow-moving caravan passed before attaining the mountains. The first was agriculturally rich, a magnificent prairie land, possessing abundant rain, fertile soil, and sufficient timber along the numerous watercourses, delighting the eye in every direction. The 150 miles, stretching from the 98th meridian to the 101st, brought a notable change.

The green rolling hills began to sink away into monotonous plains; the soil became less rich and was streaked with alkali; the waters of the streams diminished and grew unfit to drink, while vegetation became dwarfed and scanty. The cactus, the sagebrush, and the prairie dog were much in evidence. Suffocating dust rose from the trail under the horses’ feet. The third division of the journey, extending to the 104th meridian, was that hilly region that led to those great mountain ranges already plainly in sight. Here, the traveler was amid rocky, barren desolation, at first a drear, grim expanse of desert but gradually improving in vegetation and water as he approached closer to the mountains.

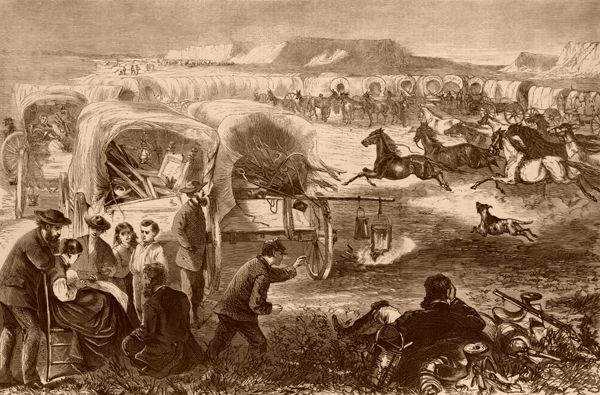

Perils of the Journey

Its surface made this a peculiar country, and its fierce storms, mirages, dangerous prairie fires, and the swiftness of attack by its mounted Indians rendered it distinct from all other frontiers. Except in the spring of the year, the prairie trails were easily followed. In a time of rain, the fords across the streams became dangerous, the prairie roads were transformed into quagmires, and no shelter was obtainable. The storms, at whatever season they occurred, were fierce and terrific. Those of summer were cyclonic, often causing significant damage, while in winter, the awful blizzard was almost certain death to any unfortunate caught unprotected upon the open plain. During the summer season, after the prairie grass had become long and dry, destructive fires raging over immense districts threatened terrible disaster to all in their course.

When driven by strong winds, such a fire became a veritable traveling furnace, bringing death to everything in its passage. The fleetest horse could not outrun its leaping flames, and the only probability of escape lay in prompt back-firing. At night, the glare of miles of flame made a magnificent spectacle if the observer could view the scene from some safety point.

Perhaps the most distressing phenomena of the Great Plains were the mirages. These were more noticeable in the south, being particularly vivid in the neighborhood of the Cimarron Desert. A sparkling river or a gleaming lake would suddenly appear amid the gray desolation. Everything would seem perfect, a breeze rippling the water, the shores distinctly outlined, yet it all faded away upon approach. Occasionally, the mirage would assume other forms — a large caravan or a splendid city, but it was a dissolving picture that enticed many a wearied traveler.

The Flora and Fauna

Flora and fauna of this vast region during the years of its invasion by the white man may be briefly summarized. The most important and practically the only tree was the Cottonwood. The best-known species was the broad-leaved, found along the lower watercourses, where the trunk occasionally attained five feet in diameter, with a height of seventy. Higher up in the foothills, the leaf became narrower. Cottonwood groves were favorite camping places on the Long Trail, furnishing fuel, logs for huts, and even food for horses. The bark was nutritious, and the animals liked it and thrived upon it and oats. The quaking ash was found in some of the valleys, usually growing in small compact copses. It was good wood for fuel. Pine, spruce, balsam, and fir abounded toward the mountains, while cedars were numerous but distorted and misshapen by the never-ceasing winds. Along most prairie streams were willow growths, often forming extensive thickets, almost impenetrable and closely crowding the bank.

Although the plains and most of the foothills and badlands were destitute of trees, occasional extensive forests became celebrated. The country of the Black Hills was heavily wooded. On the headwaters of the Neosho River was the famous forest of Council Grove, an excellent camping spot for caravans bound for Santa Fe. The Big Timbers of the Arkansas River consisted of a large grove of cottonwoods extending for several miles along the northern bank of that stream, a little distance below the site of Bent’s Fort, Colorado.

The Cross Timbers, composed chiefly of dwarfish and stunted trees, was farther south, extending from the Brazos River in Texas northwest to the Canadian River. A branch ran westward across the Canadian North Fork. On the more open plains of the north, the only growth was sagebrush and greasewood, while to the south, the cactus and the Spanish bayonet reigned supreme. In Colorado, the prickly pear was common, and on the dry plains of New Mexico, the giant cactus took weird, fantastic forms.

But, the most important vegetation of the entire region was the grasses. There were extensive barren spots and dry, desolate deserts, but generally, no region in the world ever excelled in the Plains as a grazing country. The growth was luxuriant on the lower prairies and in the stream bottoms, yet even upon the high plains, the tablelands and hills were found grasses of value. One peculiarity of these grasses is that they retain their nutritional power after the season of growth is over, even under winter snow. The three chief ones were the gramma grass, the buffalo grass, and the bunchgrass. Of these, the last was the most widespread and valuable.

In this vast region, the most important animals were the buffalo because of their number and their value to the Indians. The buffalo furnished sustenance for all the tribes of the Plains. Almost everything the buffalo furnished the Indian required — his food, bed, clothes, weapons of war and chase, boats, saddles, and most of the articles required for domestic use. The story of the buffalo can never be written in its entirety. Beyond doubt, the range of these strange shaggy beasts, called by the first Spanish explorers “deformed cattle,” at one time extended from the Rocky Mountains to the Alleghanies. But, steadily, they were forced westward. It is impossible to contend that the advance of the white man caused this retreat, for it largely predated white occupancy.

As early as 1807, the buffalo’s range receded as far as the 97th meridian. When first known to early explorers of the Plains, the great herds roamed from the Missouri River to the Rockies and from near the Gulf to 60 degrees north latitude.

Within the memory of men of the time, the multitude of these animals was almost beyond belief. No enumeration was ever satisfactory, but it is incontrovertible that they numbered millions upon millions. Railroad trains and steamboats have been held for hours to permit vast herds to pass. Innumerable trails worn by their hoofs remained visible for years. The slight statistics relating to their slaughter in later years are evidence of the vastness of their original numbers. The American Fur Company in 1840 sent to St. Louis 67,000 robes, and in 1848, 110,000. Twenty-five thousand buffalo tongues were brought to that city the same year. As early as 1860, it was estimated that at least 250,000 buffalo were being killed yearly. As late as 1871, Colonel Richard Irving Dodge wrote of riding for 25 miles in western Kansas through an immense herd, the whole country about him appearing as a solid mass of moving buffalo. In that year, the animals moved northward on their annual migration in a column from 25-50 miles wide and of unknown depth from front to rear. In the later migrations, as observed by whites, the buffalo columns usually crossed the Arkansas River somewhere between Great Bend, Kansas, and Big Sand Creek, Colorado. Colonel Dodge estimated that in the three years between 1872-74, at least five million buffalo were slaughtered for their hides.

Other animals also made their homes on the Great Plains. Along nearly all the streams was to be found the beaver, while out upon the prairies, far from his mountain lair, wandered the ferocious grizzly bear searching for food. The black bear seldom left the foothills. Elk, various species of deer, and antelope were numerous. The wolf was the vilest of the inhabitants of the Plains. The gray wolf was most prominent and troublesome, although the coyote made the night hideous with its unending yowls. Panthers and wildcats were frequently encountered, while the prairie dog was always in evidence in the more desolate regions.

However, next to the buffalo, the Plains’ most important animal was the wild horse. The horse was a comparatively recent arrival, not native to America but introduced by the Spaniards into Mexico. It multiplied rapidly, overspreading all the southern Plains, where the Indians captured it and gradually took north. As early as 1700, it was in quite general use. The wild horses ran in droves, often of considerable size, under the leadership of a stallion. They were usually taken by the lasso, although “creasing” was occasionally employed. This consisted of shooting a rifle ball through the top of the neck to cut a nerve and render the animal for a short time insensible. Thousands were caught for the market in the early days of white occupancy, and as late as 1894, a few bands were still running free in the Texas Panhandle.

Transformation Wrought by Civilized Man

This is how the Great Plains appeared when first viewed by the eyes of white explorers. To those who came later, viewing the prairie from the windows of express trains, the original desolation of the broad expanse could scarcely be conceived.

By then, farmhouses, growing cities, and prosperous towns dotted the miles, railways annihilating the distance, while foreign trees, transplanted and cultivated with care, beautified the changing landscape. The labor and skill of civilized man, the gradual increase of rainfall, and the development of irrigation combined with working a modern miracle redeeming the arid waste. The desert was transformed into a garden.

Only occasional evidence could be seen of what once was — a sterile, savage-haunted desolation, in the midst of which adventurous souls toiled and died or struggled and achieved.

The American Frontier has always proven a developer of character and a scene of a constantly recurring contest against the perils of the wilderness and Indians. But the Plains produced a peculiar type of pioneer—a brother, indeed, to him of the Eastern woods and mountains, yet changed and marked by the environment amid which he wrought his destiny and lived his life. The story of his struggle and triumph is unsurpassed in the annals of white endeavor.

Written by Randall Parrish. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

About the Author: This article was written by Randall Parrish as a chapter of his book, The Great Plains: The Romance of Western American Exploration, Warfare, and Settlement, 1527-1870; published by A.C. McClurg & Co. in Chicago, 1907. Parrish also wrote several other books, including When Wilderness Was King, My Lady of the North, Historic Illinois, and others. However, the text as it appears here is not verbatim, as it has been heavily edited for clarity and ease for the modern reader.