By Randall Parrish in 1907

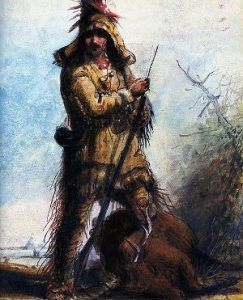

Old Trapper

While the Government was neglecting the western country of the Plains, private enterprise had been slowly prying open its secrets, and individuals were finding their uncertain way along its watercourses or across its sun-browned prairie. The fur trade was the powerful magnet that thus early drew westward hardy adventurers by the score. Very few names of those who first trod the Plains have been preserved even upon the records of the great fur companies. They were generally obscure, illiterate men, possessing little except their rifles and traps, living for long years in the depths of the wilderness, only occasionally appearing amid the haunts of pioneer civilization with their packs of furs. Sometimes they traveled in independent parties for protection against Indians, some were free trappers, and others were enrolled upon the lists of the organized fur companies and worked under orders. Either way, they necessarily led hard, wild lives, continually filled with adventure and personal peril.

These men, roughly clothed, living on wild game, their safety constantly menaced, were the true Western pathfinders, digging continually deeper into the vast wilderness each year. From their ranks came those competent guides who were later to lead organized expeditions to the Western Ocean. During the 40 years following the Louisiana Purchase, the people of the East possessed hardly the slightest conception of its immense value. The one considerable commercial attraction it offered during this period was its wealth of furs, and this was its sole business of importance for nearly half a century.

Hiram Martin Chittenden, in his book, The American Fur Trade of the far West, said:

“The nature of this business determined the character of the early white population. The roving trader and the solitary white trapper first sought out these inhospitable wilds, traced the streams to their sources, scaled the mountain passes, and explored a boundless expanse of territory where the foot of the white man had never trodden before. The far West became a field of romantic adventure and developed a class of men who loved the wandering career of the native inhabitant rather than the toilsome lot of the industrious colonist. The type of life thus developed, though essentially evanescent and not representing any profound national movement, was a distinct and necessary phase in the growth of this new country. Abounding in incidents picturesque and heroic, its annals inspire an interest akin to that which belongs to the age of knight-errantry. For the free hunter of the far West was, in his rough way, a good deal of a knight-errant. Caparisoned in the wild attire of the Indian and armed cap-a-pie for instant combat, he roamed far and wide over deserts and mountains, gathering the scattered wealth of those regions, slaying ferocious beasts and savage men, and leading a life in which every footstep was beset with enemies, and every movement pregnant of peril. The great proportion of those intrepid spirits who laid ‘down their lives in that far country is impressive proof of the jeopardy of their existence. All in all, the period of this adventurous business may justly be considered the romantic era of the history of the West.”

So valuable was this preliminary work in exploration that the able historian of the movement seems fully justified in his statement that these often unknown men were the true pathfinders and not those official explorers who came later yet have been accorded the proud title. Nothing in western geography was ever discovered by Government expeditions after 1840. It was every mile of it known previously to traders and trappers.

Brigham Young was led to the valley of Great Salt Lake by information furnished by these men; in the war with Mexico, the military forces were guided by those who knew every trail and mountain pass; they were veterans of the fur trade who pointed John Charles Fremont to the Pacific; and when the rush of emigration finally set in toward Oregon and California, the very earliest of those travelers found already made for them a highway across the continent.”

Some Noteworthy Trappers

At how early a date adventurous free trappers invaded the Great Plains is impossible to state. French-Canadians undoubtedly drifted down from the north, through the country of the Sioux, well back in the 18th century, possibly even penetrating as far as the Arkansas River, where they came in contact with the Spanish outposts. As early as 1800, American hunters had advanced up the Missouri River as far as the villages of the Mandan Indians and had trapped upon the waters of the Platte River. In 1804 we know that two Illinois men, Forest Hancock and Joseph Dickson, were trapping beaver on the Yellowstone River, and there must have been scattered here and there, others whose names have not been preserved.

In 1807, John Colter, a member of Lewis and Clark’s party, was discharged on the Missouri River and immediately turned back into the wilderness, where he remained for years, making important discoveries, including that region now known as Yellowstone Park.

John Potts, another Lewis and Clark man, accompanied him until Indians killed him. The whole story of these individual wanderers, over plain and mountain, can never be written. Very few of the names or the adventures met with have been preserved, and most of the men perished alone in the wilderness.

Organized Fur-Traders

Manuel Lisa founded the St. Louis Missouri Fur Trading Company

Manuel Lisa of St. Louis, Missouri, is the earliest name of any prominent among organized fur traders. With him were Pierre Menard and William Morrison of Kaskaskia, Illinois. As early as 1807, these men began operations on the Plains, gradually advancing into the mountains, establishing trading posts along the Missouri River and as far away as the mouth of the Big Horn River. These men were compelled to fight the Indians and conduct trade with them, and their yearly reports were as full of adventure as of business. Of all the Plains tribes, the Arikara of South Dakota caused the most trouble, although the Sioux were also frequently found hostile. In the mountains, the Blackfeet were almost continually upon the warpath.

Adventures of Ezekiel Williams

The adventures of a party under Ezekiel Williams occurred as early as 1807. He was a well-known frontiersman the government employed to return to his own people. This Mandan chief had accompanied Lewis and Clark to Washington after a failed military expedition. Twenty men started with him. Having safely performed this assigned duty, Williams and his party started west into the mountains on a trapping trip, dividing into two detachments when they arrived at the mouth of the Yellowstone River.

The Indians becoming troublesome, Williams, with eight or ten of the men, moved south along the base of the mountains until they reached the Arkansas River. Here, another separation took place, four going to Santa Fe, New Mexico, while Williams, with five men, including two Frenchmen, struck out into the mountains. While trapping, three of them were killed, and Williams, with Jean Baptiste Chaplain and a Frenchman named Parteau, sought protection among the Arapaho Indians on the South Platte River. They passed a miserable winter, but in the spring, Williams got away and floated down the Arkansas River in a canoe for over 400 miles. He was captured by Kansas Indians and robbed of his furs but finally reached safety in Missouri in September. The following May, he conducted a party back to the Arapaho village in search of his companions, only to learn they had probably been killed.

Explorations by Employees of the Fur Companies

Gathering of the Trappers, 1904, Frederic Remington

The great fur companies had little to do with the Plains except traverse them in their journeys back and forth between the market at St. Louis, Missouri, and the mountains. In the earlier days, there was some trapping of beaver along the prairie streams, but this was usually done independently. In this work, nearly every watercourse between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains had been explored by daring adventurers, often traversing the wilderness alone. Yet, the main supply of furs was sought in the mountains, and it was to these that the great fur companies dispatched their men, generally by boats up the Missouri River. However, occasionally parties struck directly across the intervening Plain, usually following the valley of the Platte. Of the two methods, it would almost seem as though by water was the more difficult. Against a swift current, heavily laden keelboats were slowly hauled with 20 men along the shore, pulling the clumsy barge using a line fastened high enough to be out of brushwood. The voyageurs poled single file where the water was shallow, facing the stern and pushing with all their power. In deeper water, oars were utilized, but in any case, it was slow, hard work involving months of unremitting labor.

The same year Manuel Lisa first organized the Missouri Fur Company, John Jacob Astor commenced operations on the Pacific Coast. There began an open war between these two companies to control the fur trade. The North West Company also became involved in the hostilities. Regarding the occurrences in the far Northwest, the hostilities were more or less connected with the movement of expeditions across the Plains. One of the most important of these was led by William P. Hunt for the Pacific Fur Company, which left St. Louis in the Spring of 1812. His company had over 60 men, and much toil and suffering were encountered.

Some of the way, it became a race between his party and representatives of the Missouri Fur Company. Hunt’s party ascended the Missouri River as far as the mouth of the Big Cheyenne River. Here, they left their boats and followed the general course of that stream to the base of the Black Hills; then, they traveled westward to the valley of the North Platte River.

They were almost a year in reaching the Pacific, their circuitous route measuring nearly 3,500 miles. A year later, a party consisting of Robert Stuart, McLellan, Crooks, and two Frenchmen, traveled east from Astoria. On the way, probably in southern Wyoming, they met a trapper, Miller, who had just escaped from the Arapaho Indians. These same Indians succeeded in running off their horses, and they were compelled to perform the remainder of their journey to the Missouri River on foot. Their sufferings in the mountains had been intense, but after reaching the Plains, they had little trouble. They followed the Platte River through its entire course, the first party on record to do so.

The Ashley Expedition

In 1822 William H. Ashley came into prominence, being connected with the American Fur Company. That year, he helped Alexander Henry erect a trading fort on the Yellowstone River, and a year later, he started up the Missouri River with 28 men bound for that post. On the way, they were attacked by Arikara Indians and driven back, having 14 killed and ten wounded. Undaunted by this, Ashley enlisted 300 followers and, in 1824, struck out across the Plains, following the Platte River to the South Pass and exploring the Sweetwater River.

He pushed through the mountains to Utah Lake, built a fort there, and sold out his interest to several of his men, Jedediah S. Smith, William L. Sublette, and David E. Jackson, two years later. These were well-known names among early trappers and traders; Smith had reached California by way of Utah and Nevada as early as 1826.

In the service of both Ashley and this newly formed company was James P. Beckwourth, long famous throughout the West. He claimed to have been in the mountains since 1817 and was the first to explore the South Platte River. To Smith, Sublette, and Jackson belongs the distinction of taking the first wagons across the Plains and into the mountains. Ten wagons, each drawn by five mules, were driven the entire distance from St. Louis, Missouri, to the Wind River. Each wagon carried 1,800 pounds, and they traveled from 15-25 miles a day. A year later, the same company brought out fourteen wagons, and others soon discovered this to be the easier method of crossing the Great Plains with supplies. The favorite route was northwest to Grand Island, Nebraska, and then the valley of the Platte River. A few years later, this became the Oregon Trail.

The revived Missouri Fur Company was, at about this date, under the leadership of Manuel Lisa, Joshua Pilcher, Thomas Hempstead, and Joseph Perkins, operating in the country around the South Pass in Wyoming. However, the principal territory covered by its trappers was among the Sioux, Arikara, and other Missouri River tribes. By 1830, the various organized companies must have had a regiment of men on the Plains and mountains. Of these, as individuals, very little is known. As Herbert Bancroft wrote: “It would be gratifying to be able to give a list of all the hunters and trappers previous to the period of emigration; but these men had no individual importance in the eyes of their leaders, who recruited their rapidly thinning ranks yearly, with little attention to the personality of the victims of hardship, accident, vice, or Indian hostility.”

The fur companies regarded those hunters as mere tools by which they could acquire the peltry to be found in unsettled districts, and when they became no longer serviceable by disease or death, they were cast aside. In many cases, their bodies were left unburied on the prairie. The names of a few of the more prominent have been preserved. Among them are Jefferson Blackwell, Jean Baptiste La Jeunesse, Robert Campbell, Kit Carson, Robert Newell, Joseph Meek, George Ebbert, Jean Baptiste Gervais, William Craig, William Vanderberg, Joseph Gale, Seth Ward, Mason Wade, John Parmalee, Robinson, John Larison, A.B. Guthrie, Auguste Claymore, François Legarde, Captain Maurice Maloney, Moses Harris, Francis Matthieu, Boudeau, Joseph Bissonette, John C. “Grizzly” Adams, John Sabille, and Charles Galpin.

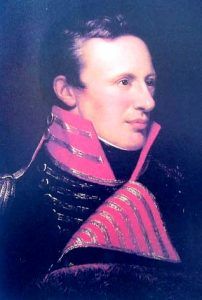

Benjamin Louis Eulalie de Bonneville

Captain Bonneville’s Expedition up the Platte

It was in 1832 that Captain E.L. Bonneville, an army officer on leave, led a party of 110 frontiersmen across the Plains to the Rocky Mountains. His purpose was profit and adventure, and his officers Joseph Walker and Gabriel Serre. They followed the route up the Platte Valley with a caravan of 20 wagons, the journey being particularly notable because oxen were used, these being the first ” bull teams” on the northern Plains. The company remained in the mountain country for over three years. Nathaniel J. Wyeth led a party of adventurers over the same route in 1832.

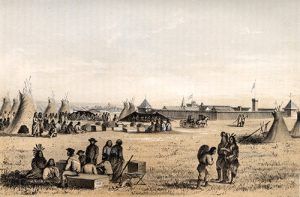

The requirements of the fur trade, carried on as it was amid hostile Indians and at a great distance from civilization, led to the early establishment of convenient points for transportation, of posts or forts.

The great fur companies usually controlled these yet were occasionally erected by individuals. In appearance, they differed little, except in size and the material used in construction. Where possible, forest trees were utilized for buildings and stockades, although on the open prairie, the earth was occasionally made to serve these purposes, and in the far south, adobe prevailed. In the later days of the trade, the majority of these forts were in the mountains; yet near enough to the western edge of the Plains to deal with the Plains Indians, but earlier, one can trace the slow advance of the trapper into the wilderness by the posts thus built along his way. Between 1807 and 1843, over 140 posts were erected throughout the Western country.

French Forts in the Valley of the Missouri River

Fort Randall, South Dakota

Fort Orleans, built by the French under M. Bourgemont, was the first of the Missouri River posts, dating back to 1772, and stood upon an island five miles below” the mouth of the Grand River. There is a tradition that Indians once attacked it, and all the residents were massacred. At least three posts were a little later established in the Osage Valley but acquired no particular importance. Fort Osage, or Fort Clark, stood near the site of Sibley, Missouri, below the mouth of the Kansas River. It later became a Government fort and was garrisoned until 1827. Francis G. Chouteau, a famous trader, built two posts in the country of the Kanza Indians. The first was destroyed by flood in 1826, but the second, about ten miles up the Kansas River, was maintained for many years. An old French fort, whose history is unknown, stood on the Kansas River shore opposite the upper end of Kickapoo Island, well back among the bluffs. It was in ruins as early as 1819. A post, erected by Joseph Robidoux, and known as Blacksnake Hills, stood on the present site of St. Joseph, Missouri. Several posts were built at Council Bluffs, Iowa, but their names have been forgotten. This was a famous trading point, but the Council Bluffs of those earlier years was 25 miles above the modern city of that name and on the opposite side of the river, being about where the little town of Calhoun now stands. In the 50 years following the Lewis and Clark Expedition, less than 20 trading forts were erected between this point and the mouth of the Platte River. Probably the oldest of these was Bellevue, which is believed to have been established in 1805. The most important, however, was Fort Lisa, Nebraska, founded in 1812 and situated six miles below old Council Bluffs.

Similar posts were found opposite the modern town of Onawa, Iowa, near the mouth of the Big Sioux River and just below the mouth of the Vermilion River. Halfway between the Vermilion and the James Rivers stood another, while Ponca Post was beside the mouth of the Niobrara River. Trudeau’s House, sometimes called Pawnee House, was occupied for trade as early as 1796. It was on the left bank, above and nearly opposite old Fort Randall. In the neighborhood of Chamberlain, South Dakota, were several forts operated by different fur companies as early as 1810. Among them were Recovery, Brasseaux, Lookout, Kiowa, and Defiance. Kiowa, established in 1822, was the largest and commercially the most important.

It was built of logs and enclosed with a stockade of cottonwood twenty feet high. Lozzell’s Post, about 35 miles below Fort Pierre, was probably the first American trading fort built in the Sioux country and was occupied as early as 1803. It was of logs and was seventy feet square, with bastions.

Early Trading Posts

The mouth of what is now called Bad River, formerly the Little Missouri River, was prolific with trading posts. This was the nearest point on the Missouri River to the Black Hills and the upper Platte Valley. When the first fort was established is unknown, but the more famous in the early days were Forts Tecumseh and Pierre. The latter was extensive, containing about two and a half acres of land. Scattered throughout the Sioux country, numerous small posts were built. There were three in the valley of the James, besides one at the forks and one at the mouth of the Cheyenne River, one at the Arikara villages, and others on the Cherry, White, and Niobrara Rivers. These, however, were not essential or permanent structures. Near the Mandan tribe were several forts, the earliest of which was built by Lewis and Clark in 1804, while Manuel Lisa occupied the ground a little later. His post later became known as Fort Vanderburgh. Beyond this point, we need not go up the Missouri River except to mention the largest and most important trading forts, Fort Union, at the mouth of the Yellowstone River. Probably, this was first built in October 1828. In size, it was 240 by 220 feet, surrounded by a palisade a foot thick and twenty feet high. The bastions were of stone, surmounted by pyramidal roofs, the walls pierced for defense. A very large number of men were employed here, and Indians journeyed from great distances to trade.

Forts along the Eastern Base of the Rockies

Leaving this northern mountain country and passing southward, several trading posts were established along the eastern base of the Rockies, whose dealings were principally with the Indians of the Plains. The Portuguese Houses, near the junction of the North and South Forks of the Powder River, were occupied at a very early date and were in ruins in 1859. They were erected by a trader named Antonio Mateo. James Bridger averred that, at one time, this post successfully resisted a siege of forty days by the Sioux. Fort William, named for William L. Sublette, stood at the junction of the North Platte and Laramie Rivers. It was built in 1834 and, after an interesting history as a trading post, was sold to the Government and rechristened Fort Laramie.

Fort Platte was an unimportant post, erected about 1840, on the right bank of that stream. La Bonti was a temporary trading house occupied in 1841 at the mouth of La Bonti Creek. In the valley of the South Platte River, about thirty miles below the present site of Denver, Colorado, were several trading establishments whose names and histories have not been preserved. Fort Lupton, also known as Fort Lancaster, stood on the right bank of the South Platte River, two miles above the mouth of the Saint Vrain River. It was built of adobe. Fort St. Vrain was at the mouth of that tributary and was prominent about 1841 when in charge of Marcellus Saint Vrain. Two other posts were in this neighborhood, but their names are not on record.

Trading Posts in the Valley of the Arkansas River

Zebulon Pike, early 1800s.

The valley of the Arkansas River was long occupied by the fur traders, but as these were largely independent operators, their posts were mainly of a temporary character. The earliest dates back to 1763 and was situated close up to the foot of the mountains, but the name of the daring adventurer is unknown. In 1806, Lieutenant Zebulon Pike built a redoubt just above the mouth of Fountain Creek, and it is believed that Chouteau and De Munn occupied a house in the same neighborhood in 1815-1817

In 1821, Jacob Fowler erected a log structure on the present site of Pueblo, Colorado, but his stay there was brief. John Gannt and Jefferson Blackwell, who were successful traders with the Arapaho, had a post six miles above Fountain Creek in 1832, and ten years later, at the mouth of that same stream, either James Beckwourth or George Simpson built a fort that became known as the Pueblo.

In 1843, there were two posts, names unknown, about five miles above Bent’s Fort, inhabited by French and Mexicans. Their principal business seems to have been smuggling across the Mexican-American line. The lower Arkansas River had no post of importance and was not greatly frequented by trappers. That known as Glenn’s is the only one worthy of mention and stood about a mile above the mouth of the Verdigris River, not far from the later site of Fort Gibson, Oklahoma. It was probably abandoned as early as 1821.

Bent’s Fort, or Fort Williams, was the one important trading post of the southern Plains. This stood on the north bank of the Arkansas River, about halfway between the present towns of La Junta and Las Animas, Colorado. It was erected by three Bent brothers, all famous as Western frontiersmen, in 1829. It became noted in the fur and Santa Fe trades, a great rendezvous for trappers and a stopping place for all the wanderers of the Plains. At times, hundreds of men, women, and children were gathered in and about its walls, and many were the stirring incidents of its romantic history. It was 150 by 100 feet in size, the longer sides running north and south. The walls were of adobe, six feet thick at the base and seventeen high. The single entrance was upon the east. In 1839, this fort had in its employ nearly a hundred men. Its trade was with the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Comanche. Rather than sell to the Government at a price less than he believed it worth, Colonel William Bent deliberately destroyed the buildings in 1852. In the early 1900s, the ruins were still visible. Today, the fort has been restored.

By Randall Parrish in 1907, compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2022.

Also See:

Trading Posts and Their Stories

List of Old West Explorers, Trappers, Traders & Mountain Men

Scouts, Frontiersmen, Trappers & Traders Photo Gallery

About the Author: Trappers, Traders & Pathfinders was written by Randall Parrish as a chapter of his book, The Great Plains: The Romance of Western American Exploration, Warfare, and Settlement, 1527-1870; published by A.C. McClurg & Co. in Chicago, 1907. Parrish also wrote several other books including When Wilderness Was King, My Lady of the North, Historic Illinois, and others. The text as it appears here; however, is not verbatim as it has been edited for clarity and ease of the modern reader.