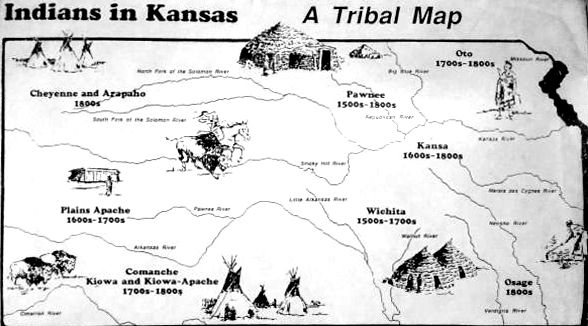

From a period extending far back into the past — far back of any written record — the Kanza claimed, as a nation, the region that they ceded to the United States by the treaty of June 1825.

From the time that Father Marquette inscribed the name of the “Kanza” nation on his map of 1673, a half-century elapses before the name again appears; when special mention of the “Canzas” is made by Etienne Venyard, Sieur de Bourgmont, commander at Fort Orleans, who passed directly through Kansas from east to west, and north of the Kansas River in 1724, on his expedition to the Padoucas, in the West. He was accompanied by delegations from several Eastern tribes, their principal chiefs and warriors. The “Kanza” delegation was conspicuous among these — the general rendezvous for the other tribes were at the Kanza village on the Missouri River. Monsieur de Bourgmont especially notes the hospitality of the tribe and their generous treatment of their visitors in his journal.

There were formerly two Kanza villages on the Missouri River. The lower, about 40 miles above the junction of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers, was situated on the west bank, between two high bluffs; the upper was a little above the mouth of Independence Creek, on the south bank of the river, and is described as having been located on “an extensive and beautiful prairie.” It was called the “Village of the Twenty-four.”

When Captain Meriwether Lewis of the Lewis and Clark expedition visited the sites of these old villages in 1804, every trace of the lower had disappeared. On a hill, a little in the rear, were the remains of an old French fort, of which the general outline of the fortification and the ruins of the chimneys were discernible. A fine spring of water was found in the vicinity. There is no clue to the history of the parties who built or occupied the fort, but the supposition is that the Indians destroyed them.

Enough of the remains of the upper village could be distinguished to show that it was pretty extensive.

The Kanza were driven from their settlements on the Missouri River by the inroads of the Iowa and Sac tribes, who were tolerably well-supplied with firearms because of their intercourse with the traders of the Mississippi Valley. The exact time at which this occurred is unknown, but it was probably 30 years before the visit of Captain Meriwether Lewis, as the Osage were driven from the Missouri River by the Sac Indians and forced farther south, onto the Osage River, about that time.

After the incursion of the hostile Indians, the Kanza, considerably reduced in number, located their principal village on the north bank of the Kansas River, about two miles below the confluence of the Big Blue River.

The site of this village was surveyed and mapped in the spring of 1880 under the supervision of Judge F. G. Adams, Secretary of the Kansas Historical Society, who described it as follows:

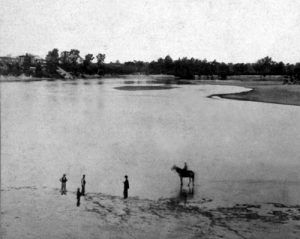

“The site is in Pottawatomie County, about two miles east of Manhattan, on a neck of land between the Kansas and Big Blue Rivers. By their courses, the rivers embrace a peninsular tract of about two miles in length, extending east and west.

At the point where the village was situated, the neck between the two rivers is about one-half mile in breadth, and the village stretched from the banks of the Kansas River northward for the greater part of the distance across toward the Blue. The site of the village is on the present farm of Honorable Welcome Wells and is crossed by the Kansas Branch of the Union Pacific Railroad.”

Although the Kanza and Osage tribes were of the same nation, their language nearly identical, and their government and customs similar, they were almost continually at war from when they were first known to Europeans until 1806. That year, the United States Government negotiated a treaty between the two nations.

A grand council was held on September 28, 1806, at the village of the Pawnee Republic, between Lieutenants Zebulon Pike and James Wilkinson on the part of the United States and various chiefs of the Pawnee, Osage, and Kanza Nations. The treaty formed between the two nations at that time, copies of which were forwarded to the several tribes through their respective chiefs, read as follows:

“In council held by the subscribers, at the village of the Pawnee Republic, appeared Wahonsongay with eight principal soldiers of the Kanza Nation on the one part, and Shinga-Wasa, a chief of the Osage Nation, with four of the warriors of the Grand and Little Osage villages on the other part. After having smoked the pipe of peace and buried past animosities, they individually and jointly bound themselves on behalf of and for their respective nations to observe a friendly intercourse and keep a permanent peace, and mutually pledge themselves to use every influence to further the commands and wishes of their great father. We, therefore, American chiefs, do require of each nation a strict observance of the above treaty, as they value the goodwill of their great father, the President of the United States. Done at our council fire, at the Pawnee Republican village, September 28, 1806, and the thirty-first year of American independence.”

(Signed),

Z. M. Pike

J. B. Wilkinson

The treaty thus formed was never broken by either nation. Their common hostility was henceforward directed mainly to the Pawnee tribe and the many marauding tribes that lived on the Western plains.

Although smaller numerically than either the Osage or Pawnee, the Kanza Nation was more warlike than the former and, from its rapidly acquired skill in the use of firearms, was dreaded by the latter. It was not many years after the visit of Lieutenant Pike before the increasing influx of traders and explorers into the country gave a new direction to the warlike propensities of the tribe, which, from its position, was able to cause much trouble and annoyance, both to those who sought to pass up the Missouri River and those who wished to cross the plains to the Rocky Mountains.

Their depredations were becoming more frequent and severe, culminating in 1819 with their firing on one of the Indian Agents and attacking and plundering soldiers attached to the command of Captain Martin, who was sent up the Missouri River with a detachment of troops the preceding fall and was obliged, during the winter, to form a hunting-camp to keep himself and party from starving.

To prevent the recurrence of similar outrages, Major O’Fallon, the Indian Agent who had been attacked, summoned the chiefs and principal men of the Kanza Nation to a council to be held at Isle au Vache in the Missouri River near the present site of Atchison, on August 18, 1819.

The Indians were absent on a hunting excursion when the messenger arrived at their village on the Kansas River but arrived at the designated place on the 23rd. On the following day, the council was held in the arbor, prepared for their reception. There were present 161 Kanza and thirteen Osage, including Na-he-da-ba, or Long Neck, one of the principal chiefs of the Kanza; Ka-he-ga-wa-ta-ning-ga, Little Chief, second in rank; Shen-ga-ne-ga, an ex-principal chief; Wa-ha-che-ra, Big Knife, a war chief; and Wom-pa-wa- ra, or White Plume, just then becoming famous. Major O’Fallon had with him the officers of the garrison and a few gentlemen connected with Major Stephen Long’s exploring expedition.

After setting forth the various grievances that the whites had suffered at their hands and impressing them with a sense of their general bad conduct, which they were assured richly merited severe chastisement, the Major held out the promise of reconciliation, provided their future behavior should merit such a favor.

The chiefs fully acquiesced in the justice of the charges brought against them and accepted the terms offered by the agent. The ceremonies were enlivened by a slight military display in the form of the firing of cannons and hoisting of flags and an exhibition of rockets and shells, which last made a more profound impression on the minds of the visitors than the eloquence of Major O’Fallon. It was afterward learned that the delegation would have been larger but for a quarrel that arose among the chiefs after they had started regarding precedence in rank. Consequently, ten or twelve returned to the village.

Professor Thomas Say, of Major Stephen Long’s exploring party, visited the nation at the village on the Kansas River during the summer of 1819 when the delegation started for the Isle au Vache council. The following account of the reception of his party, the general appearance of the village, and the government and customs of the nation at the time is taken from the report of Major Long’s expedition.

“As they approached the village, they perceived the tops of the lodges red with the crowds of natives. The chiefs and warriors came rushing out on horseback, painted and decorated and followed by great numbers on foot. Mr. Say and the party were received with the utmost cordiality and conducted into the village by the chiefs, who went before and on each side to protect them from the encroachments of the crowd. On entering the village, the crowd readily gave way before the party but followed them into the lodge assigned to them and completely and most densely filled the spacious apartment, with the exception only of a small space opposite to the entrance, where the party seated themselves on the beds, still protected from the pressure of the crowd by the chiefs, who took their seats on the ground immediately before them. After the ceremony of smoking with the latter, the object which the party had in view in passing through their territories was explained to them and seemed to be perfectly satisfactory. At the lodge of the principal chief, they were regaled with jerked bison meat and boiled corn and were afterward invited to six feasts in immediate succession.”

Mr. Say also wrote:

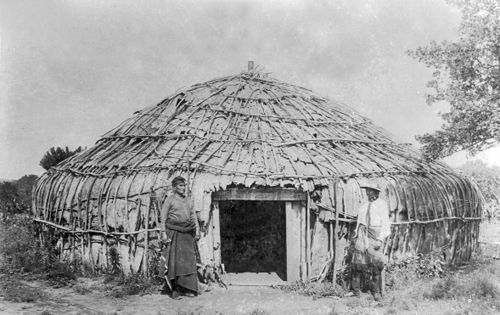

“The approach to the village is over a fine level prairie of considerable extent, passing which you ascend an abrupt bank to the right, of ten feet, to a second level, on which the village is situated in the distance, within about a quarter of a mile of the river. It consists of about one hundred and twenty lodges, placed as closely together as convenient and destitute of any regularity of arrangement. The ground area of each lodge is circular and excavated to a depth of from one to three feet, and the general form of the exterior may be denominated hemispheric.

The lodge in which we reside is larger than any other in the town, and being that of the grand chief, it serves as a council house for the nation. The roof is supported by two series of pillars, or rough vertical posts, forked at the top for the reception of the transverse connecting pieces of each series; twelve of these pillars form the outer series, placed in a circle, and eight longer ones the inner series, also describing a circle; the outer wall, or rude frame-work, placed at a proper distance from the exterior series of pillars, is five or six feet high. Poles, as thick as the leg at the base, rest with their butts upon the wall, extending on the cross-pieces, which are upheld by the pillars of the two series and are of sufficient length to reach nearly to the summit. These poles are very numerous and agreeable to the position which we have indicated, they are placed all around in a radiating manner, and support the roof like rafters. Across these are laid long and slender sticks or twigs attached parallel to each other by means of bark cord; these are covered by mats made of long grass or reeds or with the bark of trees; the whole is then covered completely with earth, which, near the ground, is banked up to the eaves. A hole is permitted to remain in the middle of the roof to give an exit to the smoke. Around the interior walls, a continuous series of mats are suspended; these are of neat workmanship, composed of a soft reed, united by bark cord, in straight or undulated lines between which lines of black paint sometimes occur. The bedsteads are elevated to the height of a common seat from the ground and are about six feet wide; they extend in an uninterrupted line around three-fourths of the circumference of the apartment and are formed in the simplest manner, of numerous sticks or slender pieces of wood, resting at their ends on cross pieces, which are supported by short notched or forked posts driven into the ground. Bison skins supply them with a comfortable bedding. Several medicine or mystic bags are carefully attached to the mats of the wall; these are cylindrical and neatly bound up. Several reeds are usually placed upon them, and a human scalp serves for their fringe and tassels. Of their contents, we know nothing.

The fireplace is a simple, shallow cavity in the center of the apartment, with an upright and projecting arm to support the culinary apparatus. The latter is very simple in kind and limited in quantity, consisting of a brass kettle, an iron pot, and wooden bowls and spoons. Each person, male and female, carries a large knife in the girdle of the breechcloth behind, which is used at their meals and sometimes for self-defense. During our stay with these Indians, they ate four or five times each day, invariably supplying us with the best pieces, or choice parts, before they attempted to taste the food themselves.”

Their food was described as consisting of bison meat and various preparations of Indian corn or maize, one of which was called “lyed corn,” known among the whites as hulled corn. They also used pumpkins, muskmelons, watermelons, and a soup made of boiled sweet corn and beans seasoned with buffalo meat.

In 1819, the hereditary principle chief was Ca-ega-wa-tan-ninga, but could maintain his authority only by the force of personal qualities; all distinction, civil and military, was a reward for bravery or generosity. There were several inferior chiefs, but they possessed little authority.

Like all the Indian tribes, the Kanza believed in a Great Spirit and had vague ideas of a future life. In their family relations, they were more honorable than many Eastern tribes. Marriage was celebrated with such ceremonies as rendered the tie more binding, and purity was one of the requisites to fit a woman for the “wife of a chief, a brave warrior or a good hunter.”

They bore the pain with the typical Indian stoicism, never complaining. They were faithful to the ties of relationship and friendship and cared for the sick and disabled. Drunkenness was rare, and insanity unknown. The women had the entire management of all domestic concerns and appeared to take pride in excelling in that department.

The first treaty between the United States Government and the Kanza Indians was concluded between Ninian Edwards and Auguste Choteau, Commissioners of the United States, and certain chiefs and warriors of the Kanza tribe, on behalf of said tribe, in 1815. It was a treaty of peace, the parties mutually agreeing to forgive any past injury, perpetuating friendly relations, and the tribe, through its chiefs, acknowledging itself under the protection of the United States and of “no other nation, power or sovereign whatsoever.”

In June 1825, treaties for the cession of their lands were made with the Kanza and Osage Nations at St. Louis, Missouri. These treaties were made by General Clarke, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, without previous authority from the Government but by the advice of Honorable Thomas H. Benton and on the strength of his assurance that the Senate would ratify them. They were duly ratified, and the necessary appropriations were made. The treaty with the Kanza was made June 3, 1825, by the terms of which the following named country was ceded: “Beginning at the entrance of the Kansas River into the Missouri River; from thence north to the northwest corner of the State of Missouri; from then westerly to the Nodaway River, thirty miles from its entrance into the Missouri River; from thence to the entrance of the Nemaha into the Missouri River, and with that river (the Nemaha) to its source; from thence to the source of the Kansas River, leaving the old village of the Pania [Pawnee] Republic to the west; from thence on the ridge dividing the waters of the Kansas River from those of the Arkansas River to the western boundary line of the State of Missouri; and with that line 30 miles to the place of beginning.”

From this cession, a reservation “for the use of the Kanza Nation” was made of a “tract of land, to begin twenty leagues up the Kansas River and to include their village on that river; extending west thirty miles in width, through the lands ceded in the first article.”

About 20 half-breed reservations of one-mile square were made “to be located on the north side of the Kansas River, commencing at the line of the Kanza Reservation” (a little west of the present site of North Topeka) “and extending down the Kansas River for quantity.”

The tribe also relinquished all claim they might have to lands in Missouri at this time. In consideration of the cession of land and relinquishment of such claim, the United States agreed “to pay to the Kanza Nation of Indians $3,500 per annum for twenty successive years, at their villages, or the entrance of the Kansas River, either in money, merchandise, provisions or domestic animals, at the option of the aforesaid nation; and when the said annuities, or any part thereof, is paid in merchandise, it shall be delivered to them at the first cost of the goods in St. Louis, free of transportation.

In addition to the above-named consideration, cattle, hogs, and implements of agriculture were to be supplied to them, a blacksmith provided, and persons employed to teach them agriculture.

The United States, by its Commissioner, also agreed that “thirty-six sections of good land, on the Big Blue River, shall be laid out under the direction of the President of the United States, and sold to raise a fund to be applied, under the direction of the President, to the support of schools for the education of the Kanza children within their nation.”

A part of the first payment was made at St. Louis at the time of the treaty; $2,000 in merchandise and horses being delivered to the delegation of chiefs and warriors present; the remainder was paid at the mouth of the Kansas River, near the present site of Wyandotte, in 1825.

The first Kanza Agency was established in East Kansas City in 1827, with Barnett Vasquez being the first agent. The agency was removed to the mouth of Grasshopper Creek the following year, the first payment being made in 1829 by Daniel McNair, Special Agent and Paymaster. In 1830, Marston G. Clark, Agent; Daniel Boone, farmer; Clemenent Lessent, Interpreter; Gabriel Phillibert, blacksmith, with some of the Kaw half-breeds, were living at the “Stone Agency House” on Grasshopper Creek.

The old Kanza village near the mouth of the Big Blue River was partially abandoned about the year 1830; the tribe, during that year, established several villages lower down the Kansas River. The village of American Chief was on the creek of the same name (now Mission Creek) and about two miles south of the Kansas River. This band, of about 100, had about 20 dirt lodges of good size, in which they lived until they removed to Council Grove in 1848. Hard Chief’s village, about a mile from the former, was situated on a high bluff on the south bank of the Kansas River and numbered about five hundred people and eighty-five lodges. It was about a mile and a half west of Mission Creek.

The third and largest village, that of Fool Chief, was on the north bank of Kansas River, two or three miles west of where North Topeka now stands. Mr. McCoy, in his “Annual Register of Indian Affairs” for 1835, says the Government of the United States had at that time fenced twenty acres of land, plowed ten acres, and erected for the principal chief a good hewed-log house, at the lower or Fool Chief’s village; their smithery, agency house and house for the residence of their teacher of agriculture being within the Delaware country, twenty-three miles east of the Kanza lands. Mr. McCoy gives the whole number of the tribe as about 1,606, their agent then being R.W. Cummings, and their interpreter Joseph James. In 1830, Reverend William Johnson of Howard County, Missouri, was appointed by the Missouri Methodist Conference as a missionary to the Kanza tribe. He resided among them for two years, was then transferred to the Delaware Mission, then to the Shawnee, and, in 1835, returned to his labors among the Kanza. In the spring of the same year, the Government farm was removed to the vicinity of the upper villages, 300 acres being selected for the purpose on the north bank of the Kansas River, just east of the present site of Silver Lake Township, and about 300 acres in the valley west of Mission Creek and south of the Kansas River.

In the summer of 1835, mission buildings were erected on the northwest corner of the farm lying south of the river. The buildings consisted of a hewn-log cabin, two stories high, 18 feet wide by 36 feet long, with a smokehouse, kitchen, and outbuildings. Mr. Johnson and his wife were removed into the mission house in September and, for the next seven years, labored faithfully for the good of the Kaws. Mr. Johnson died in April 1842 at the Shawnee Mission of pneumonia, contracted from the exposure incident on the journey to that place. Mr. Cornetzer and afterward, Reverend George W. Love had charge of the mission for a short period. Still, the prosperity of the institution waned from the time of the death of its first efficient missionary, and, after a few years, it was absorbed in the Shawnee Mission. In 1845, Reverend J. T. Peery established a manual labor school on a small scale at the mission, which continued for one year.

On January 14, 1846, the Kanza ceded to the United States “two million of acres of land on the east part of their country, embracing the entire width, and running west for quantity.”

This cession comprised the reservation afterward granted to the Pottawatomie, including all the improvements made by the Government. The Kanza were removed to the vicinity of Council Grove, now in Morris County, where they received a grant of 256,000 acres. A branch of the Shawnee Methodist Mission was established among them. Hard Chief’s village was established on the north bank of the Cottonwood River. The village of Columbia was afterward founded by Thomas F. Huffaker, who, with other Government officials, accompanied the Indians to the new location.

They gradually deteriorated in number and civilization. After they learned to love liquor, all efforts for their advancement proved futile. The tribe among whom “drunkenness was rare” ceased to exist, and before they were removed to the Indian Territory, they were perhaps the most degraded tribe in Kansas.

On October 5, 1859, a treaty was made by which a portion of the tribal reservation was set apart and assigned in severalty to various individuals of the tribe.

On May 8, 1872, an act was passed for the appraisal and sale of their lands and their final removal from the State of Kansas to a reservation in Indian Territory. On May 27, 1872, over the strong protests of Chief Allegawaho and his people, the Kanza were moved to a 100,137-acre site in northern Oklahoma.

Their number in 1882 was reduced to about 200, a feeble, poverty-stricken remnant of the powerful nation from which the fair State of Kansas derived its name.

But, even at their new reservation in Oklahoma, their land would not be safe. The Kaw Allotment Act of 1902 disbanded the Kaw tribe as a legal entity, allocated its land to enrolled members, and transferred 160 acres to the federal government. The Act was primarily the work of Charles Curtis — a distinguished one-eighth blood member of the tribe who eventually served as Vice-President of the United States under President Herbert Hoover and who, in 1902, was a Kansas congressman and member of the powerful House Committee on Indian Affairs. Congressman Curtis, together with his three children, received about 1,625 acres.

A significant minority of full-blooded Kanza, whose political power in the tribe had declined dramatically since the forced removal from Kansas, opposed the Allotment Act until the tribe was reorganized under federal authority in 1959 factionalism and political struggles over tribal affairs were commonplace.

Following allotment in 1902, the Kaw people retained 260 acres near the Beaver Creek confluence with the Arkansas River until the mid-1960s, when their former reservation land was inundated by the Kaw Reservoir constructed by the United States Corps of Engineers on the Arkansas River just northeast of Ponca City, Oklahoma.

Here, dating to the late 19th century, the tribal council house, the old Washungah townsite, and the tribal cemetery were located. After negotiation with various federal and local officials, the cemetery was relocated to Newkirk, Oklahoma, and the council house to a 15-acre tract a few miles northwest of the former Beaver Creek trust lands. By subsequent Congressional action, the new council house tract was enlarged to include approximately 135 acres presently administered by the Kaw Nation as official trust lands.

Today, the Kaw Nation of Kanza people is headquartered in Kaw City, Oklahoma. The tribe has more than 3,000 members located in 48 states. More than 2,500 are enrolled members of the Kaw Nation in northern Oklahoma. The Kaw National Council adopted its present constitution on August 14, 1990.

During the long period their lands were taken away, their language usage began to taper off dramatically. This trend continued into the 20th century until only a handful of the Kanza Indians could speak the language fluently by the 1970s. Today, the tribe is working hard to preserve and revive their language. Today’s economic activities include the Kaw Nation Casino enterprise near Newkirk, travel plazas, and tobacco shops. The tribe also has developed and oversees the Kaw Housing Project near Newkirk, the Kanza Health Clinic and Wellness Center, a daycare center, a gymnasium, and a multi-purpose center, and is a member of the Chilocco Development Authority.

Kaw Nation Seal

More Information:

The Kaw Nation

698 Grandview Drive

Kaw City, Oklahoma

580-269-2552

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

About this article: The primary content is an edited rendition of the Kanza Indians as told in William G. Cutler’s History of the State of Kansas, first published in 1883 by A. T. Andreas, Chicago, Illinois. Note that the article is not verbatim, as minor corrections for spelling and punctuation, editing for clarity, and updates since the article was first written have been made.

Also See:

List of Notable Native Americans

Native American Heroes and Legends