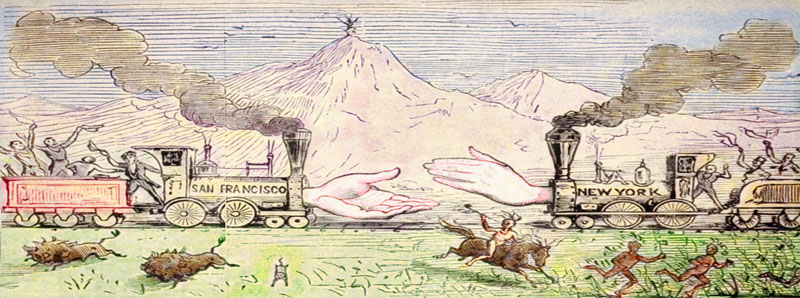

Nationally, the South struggled against the North, preventing the early location of a Pacific railway. Locally, every village on the Mississippi River from the Great Lakes to the Gulf hoped to become the terminus and had advocates throughout its section of the country. The list of claimants of the Mississippi River Valley included New Orleans, Louisiana; Vicksburg, Mississippi; Memphis, Tennessee; St. Louis, Missouri; Cairo and Chicago, Illinois; and Duluth, Minnesota. By 1860, the idea had received general acceptance; no one needed to urge its adoption in the future, but the most significant part of the work remained.

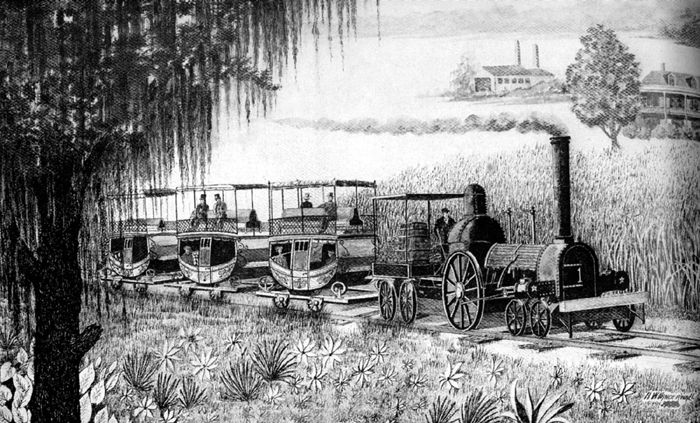

Born during the 1830s, the idea of a Pacific railway was of uncertain origin and parentage. Just as soon as there was a railroad anywhere, it was inevitable that some enterprising visionary would project one in imagination to the extremity of the continent. The railway speculation, with which the East was seething during President Andrew Jackson’s administration, was boiling over in the young West so that the group of men advocating a railway to connect the oceans was but the product of their time.

Most significant among these enthusiasts was Asa Whitney, a New York merchant interested in the Chinese trade and eager to win the commerce of the Orient for the United States. Others had declared such a road possible before he presented his memorial to Congress in 1845, but none had staked so much upon the idea. He abandoned the business, conducted a private survey in Wisconsin and Iowa, and was finally convinced that “the time is not far distant when Oregon will become… a separate nation” unless communication should “unite them to us.” He petitioned Congress in January 1845 for a franchise and land grant to accomplish the national road. For many years, he agitated persistently for his project.

The annexation of Oregon and the Southwest, coming in the years immediately after the commencement of Whitney’s advocacy, gave new points to arguments for the railway and introduced the sectional element. So long as Oregon constituted the American frontage on the Pacific, it was idle to debate railway routes south of South Pass, Wyoming. This was the only known, practicable route, and it was the course all the projectors recommended down to Whitney. However, with California winning, the other trails by El Paso, Texas, and Santa Fe, New Mexico, came into consideration and at once tempted the South to make the railway tributary to its own interests.

Chief among the politicians who fell in with the growing railway movement was Senator Thomas Hart Benton, who tried to place himself at its head. “The man is alive, full grown, and is listening to what I say (without believing it perhaps),” he declared in October 1844, “who will yet see the Asiatic commerce traversing the North Pacific Ocean—entering the Oregon River—climbing the western slopes of the Rocky Mountains—issuing from its gorges—and spreading its fertilizing streams over our wide-extended Union!” After this date, no subject was closer to his interest than the railway, and his advocacy was constant. His last word in the Senate was concerning it. In 1849, he carried off its feet the St. Louis railroad convention with his eloquent appeal for a central route: “Let us make the iron road, and make it from sea to sea—States and individuals making it east of the Mississippi River, the nation making it west. Let us… rise above everything sectional, personal, and local. Let us… build the great road… which shall be adorned with… the colossal statue of the great Columbus—whose design it accomplishes, hewn from a granite mass of a peak of the Rocky Mountains, overlooking the road… pointing with an outstretched arm to the western horizon and saying to the flying passengers, ‘There is the East, there is India.'”

By 1850, it was common knowledge that a railroad could be built along the Platte River route, and it was believed that the mountains could be penetrated in several other places. However, the process of surveying a particular railway had not begun. It is possible and perhaps instructive to make a rough grouping, in two classes divided by the year 1842, of the explorations before 1853. So late as John C. Fremont’s day, it was not generally known whether a great river had entered the Pacific between the Columbia and Colorado Rivers. Before 1842, the explorations were regarded as “incidents” and “adventures” in more or less unknown countries. The narratives were popular rather than scientific, representing the experiences of parties surveying boundary lines or locating wagon roads, of troops marching to remote posts or chastising Indians, of missionaries and casual explorers. In the aggregate, they contributed a large mass of detailed but unorganized information concerning the country where the continental railway must run. However, in 1842, Lieutenant Fremont commenced the United States’ effort to acquire accurate and comprehensive knowledge of the West. In 1842, 1843, and 1845, Fremont conducted the three Rocky Mountain expeditions, which established him for life as a popular hero. The map, drawn by Charles Preuss for his second expedition, confined itself in a strict scientific fashion to the facts actually observed and, in skill of execution, was perhaps the best map made before 1853. The individual expeditions that in the later 1840s filled in the details of portions of the Fremont map are too numerous for mention. At least 25 occurred before 1853, all extending general and particular knowledge of the West. To these was added a196 great mass of popular books prepared by emigrants and travelers. By 1853, there was good, unscientific knowledge of nearly all of the West and accurate information concerning some portions. Railroad enthusiasts could tell the general direction in which the roads must run, but no road could be located well without a more comprehensive survey than had yet been made.

The agitation of the Pacific railway idea was founded almost exclusively upon general and inaccurate knowledge of the West. The line’s location was naturally left for the professional civil engineer; its popular advocate contented himself with general principles. Frequently, these were sufficient, yet, as in the case of Thomas Benton, misinformation led to the unquestionably harmful waste of strength upon routes. However, there was a slight danger of the United States being led into an unwise route since the diversity of routes suggested a deadlock. Until after 1850, in proportion to the idea being received unanimously, the routes were fought with increasing bitterness. Whitney was shelved in 1852 when choosing routes had become more important than the construction method.

In 1852-1853, Congress worked on one of the many bills to construct the much-desired railway to the Pacific. It was discovered that an absolute majority in favor of the work existed. Still, the enemies of the measure, virulent in proportion as they were in the minority, were able to sow well-fertilized dissent. They admitted and gloried in the intrigue that enabled them to command through the time-honored division method. They defeated the road in this Congress. However, when the army appropriation bill came along in February 1853, Senator William Gwin asked for an amendment to a survey. He doubted the wisdom of a survey since “if any route is reported to this body as the best, those that may be rejected will always go against the one selected.” But he admitted himself to be a drowning man who “will catch at straws.” He begged that $150,000 be allowed to the President for a survey of the best routes from the Mississippi River to the Pacific, the survey to be conducted by the Corps of Topographical Engineers of the regular army. With a non-committal measure like this, the opposition could make slight resistance. By a vote of 31 to 16, the Senate added this amendment to the army appropriation bill, while the House concurred in nearly the same proportion. The first positive official act towards road construction was taken here.

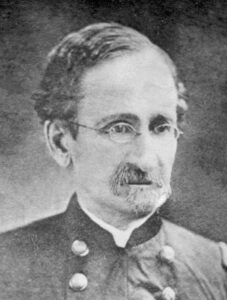

Under the orders of Jefferson Davis, Secretary of War, well-organized exploring parties took to the field in the spring of 1853. Farthest north, Isaac I. Stevens, bound for his post as first governor of Washington Territory, conducted a line of survey to the Pacific between the parallels of 47° and 49°, north latitude. South of the Stevens survey, four other lines were worked out. Near 41° and 42° parallels, the old South Pass route was again examined. John C. Fremont’s favorite line, between 38° and 39°, received consideration. A 35th parallel route was examined in great detail, while on this and another along the 32nd parallel, the most friendly attentions of the War Department were lavished. The second and third routes had few important friends. Because he was a first-rate fighter, Governor Isaac Stevens secured full space for the survey in his charge. But the 32nd and 35th parallel routes were expected to make good.

Governor Stevens left Washington on May 9, 1853, for St. Louis, Missouri, where he made arrangements with the American Fur Company to transport a large part of his supplies by river to Fort Union, North Dakota. From St. Louis, he ascended the Mississippi River by steamer to St. Paul, Minnesota, near which city Camp Pierce, his first organized camp, had been established. Here, he issued his instructions and worked to shape his party—to say nothing of his half-broken mules. “Not a single full team of broken animals could be selected, and well-broken riding animals were essential, for most of the gentlemen of the scientific corps were unaccustomed to riding.” One of the engineers dislocated a shoulder before he conquered his steed.

The party assigned to Governor Stevens’s command was recruited concerning the varied demands of a general exploring and scientific survey. Besides enlisted men and laborers, it included engineers, a topographer, an artist, a surgeon and naturalist,199 an astronomer, a meteorologist, and a geologist. Its two large volumes of the report include elaborate illustrations and appendices on botany, seven varieties of zoology, and the geographical details required for the railway.

In its various branches, the expedition attacked the northernmost route simultaneously in several places. Governor Stevens led the eastern division from St. Paul. A small body of his men, with much of the supplies, were sent up the Missouri in the American Fur Company’s boat to Fort Union to make local observations and await the governor’s arrival. United there, the party continued overland to Fort Benton, Montana, and the mountains. Six years later than this, it would have been possible to ascend by boat to Fort Benton, but as yet, no steamer had gone much above Fort Union. From the Pacific end, the second main division operated. Governor Stevens secured the recall of Captain George B. McClellan from duty in Texas and his detail in command of a corps, which was to proceed to the mouth of the Columbia River and start an eastward survey. In advance of McClellan, Lieutenant Saxton was to erect a supply depot in the Bitter Root Valley, then cross the divide and make a junction with the main party.

According to Governor Stevens’s reports, his survey was a triumphal progress. To his threefold capacities as commander, governor, and Indian superintendent, nature had added a magnifying eye and an unrestrained enthusiasm. No formal expedition had traversed his route since the day of Lewis and Clark. The Indians could still be impressed by the physical appearance of the whites. His vanity led him to congratulate himself on the antecedent wisdom that had warded off the danger at each success or escape from an accident. But withal, his report was thorough, and his party was loyal. The voyageurs whom he had engaged received his special praise. “They are thorough woodsmen and just the men for prairie life also, going into the water as pleasantly as a spaniel and remaining there as long as needed.”

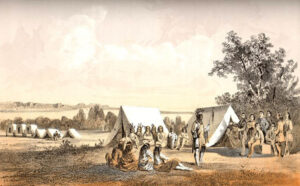

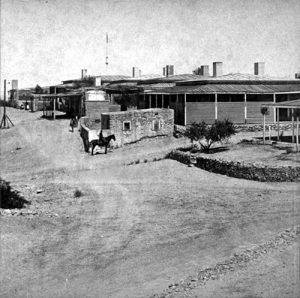

Across the undulating fertile plains, the party advanced from St. Paul with little difficulty. Its draught animals steadily improved in health and strength. The Indians were friendly and honest. “My father,” said Old Crane of the Assiniboin, “our hearts are good; we are poor and have little… Our good father has told us about this road. I do not see how it will benefit us. I fear my people will be driven from these plains before the white men.” In 55 days, Fort Union was reached. Here, the American Fur Company maintained an extensive post in a stockade 250 feet square and carried on an extensive trade with “the Assiniboine, the Gros Ventre, the Crow, and other migratory bands of Indians.” At Fort Union, Alexander Culbertson, the agent, became the guide of the party, which proceeded west on August 10. It was nearly 400 miles from Fort Union to Fort Benton, which stood on the Missouri River’s left bank, some 18 miles below the falls. Though less friendly than that East of the Missouri, the country offered little difficulty to the party, which covered the distance in three weeks. A week later, on September 8, a party sent on from Fort Benton met Lieutenant Rufus Saxton coming east.

The chief problems of the Stevens survey lay West of Fort Benton, in the passes of the continental divide. Lieutenant Saxton had left Vancouver, Washington, early in July, crossed the Cascades with difficulty, and started up the Columbia River from the Dalles on July 18. He reached Fort Walla Walla on the 27th and proceeded thence with a half-breed guide through the country of the Spokan and the Cœur d’Alene. Crossing the Snake River, he broke his only mercurial barometer and was forced to rely on his aneroid after that. Deviating to the North, Northossed Lake Pend d’Oreille on August 10 and reached St. Mary’s village in the Bitter Root Valley on August 28. St. Mary’s village, among the Salish Indians, had been established by the Jesuit fathers and had advanced considerably as Indian civilization went. Here, Saxton erected his supply depot, from which he advanced with a smaller escort to join the main party. Even in the mountains’ heart, the country always exceeded his expectations. “Nature seemed to have intended it for the great highway across the continent, and it appeared to offer but little obstruction to the passage of a railroad.”

Acting on Saxton’s advice, Governor Stevens reduced his party at Fort Benton, stored much of his government property there, and started west with a pack train for greater speed. He moved on September 22, anxious lest snow should catch him in the mountains. At Fort Benton, he left a detachment to make meteorological observations during the winter. Among the Flatheads, he left another under Lieutenant Mullan. On October 7, he returned from the Bitter Root Valley for Walla Walla, Washington. On the 19th, he met McClellan’s party, which had been spending a problematic season in the passes of the Cascade range. Because of the overcautious advice that McClellan gave him, and since his animals were tired out with the summer’s hardships, he practically ended his survey for 1853. He pushed down the Columbia to Olympia and his new territory.

The energy of Governor Stevens enabled him to make one of the first of the Pacific railway reports. His was the only survey from the Mississippi River to the ocean under a single commander. Dated June 30, 1854, it occupies 651 pages of Volume I of the compiled reports. In 1859, he submitted his “narrative and final report,” which the Senate ordered Secretary of War John B. Floyd to communicate in February. This document is printed as a supplement to Volume I but consists of two large volumes commonly bound together as Volume XII of the series. Like the other volumes of the reports, this one is filled with lithographs and engravings of fauna, flora, and topography.

Lieutenant Edward G. Beckwith of the Third Artillery, in the summer of 1854, surveyed the 42nd parallel route. East of Fort Bridger, Wyoming, the War Department felt it unnecessary to make a special survey since Fremont had traversed and described the country several times. Stansbury had surveyed it carefully as recently as 1849–1850. At the beginning of his campaign, Beckwith was at Salt Lake. During April, he visited the Green River Valley and Fort Bridger, proving the entire practicability of railway construction here by his surveys. In May, he skirted the south end of Great Salt Lake and passed along the Humboldt to the Sacramento Valley. He had no important adventures and was impressed most by the squalor of the digger Indians, whose grass-covered, beehive-shaped “wiki-ups” were frequently seen. As his band approached, the Indians would fearfully cache their belongings in the undergrowth. In the morning “it was indeed a novel and ludicrous sight of wretchedness to see them approach their bush and attempt, slyly, to repossess themselves of their treasures, one bringing out a piece of old buckskin, a couple of feet square, smoked, greasy, and torn; another a half dozen rabbit-skins in an equally filthy condition, sewed together, which he would swing over his shoulders by a string—his only blanket or clothing; while a third brought out a blue string, which he girded about him and walked away in full dress — one of the lords of the soil.” It needed no particular emphasis in Beckwith’s report to prove that a railway could follow this middle route since thousands of emigrants had a personal knowledge of its conditions.

Beckwith, who started his 42nd parallel survey from Salt Lake City, had reached that point as one of the officers in Gunnison’s unfortunate party. Captain William Gunnison had followed Governor Stevens into St. Louis in 1853. His field of exploration, the route of 38°-39°, was by no means new to him since he had been to Utah with Stansbury in 1849 and 1850 and had already written one of the best books upon the Mormon settlement. He carried his party up the Missouri to a fitting-out camp just below the mouth of the Kansas River, five miles from Westport, Missouri. Like other commanders, he spent much time at the start “breaking in wild mules,” with which he advanced in rain and mud on June 23. For over two weeks, his party moved in parallel columns along the Santa Fe Trail and the Smoky Hill fork of the Kansas River. They united Near Walnut Creek on the Santa Fe Trail and soon followed the Arkansas River toward the mountains. At Fort Atkinson, Kansas, they found a horde of the Plains Indians waiting for Major Thomas Fitzpatrick to make a treaty with them. Always their observations were taken with regularity. One day, Captain William Gunnison desperately tried to secure specimens of the elusive prairie dog. On August 1, when they were ready to leave the Arkansas River and plunge Southwest into the Sangre de Cristo range, they were gratified “by a clear and beautiful view of the Spanish Peaks.”

Santa Fe Trail near “The Caches” in Ford County, Kansas.

This 39th parallel route, a favorite with Fremont, crossed the divide near the head of the Rio Grande. Its grades, which were rugged and steep at best, followed the Huerfano Valley and Cochetopa Pass. Across the pass, Gunnison began his descent of the arid alkali valley of the Uncompahgre—a valley today about to blossom as the rose because of the irrigation canal and tunnel bringing the waters of the neighboring Gunnison River. With heavy labor, intense heat, and weakening teams, Gunnison struggled through September and October toward Salt Lake in Utah territory. Near Sevier Lake, he lost his life. Before daybreak, on October 26, he and a small detachment of men were surprised by a band of young Paiute. When the rest of his party hurried up to the rescue, they found his body “pierced with 15 arrows” and seven of his men lying dead around him. Beckwith, who succeeded to the command, led the remainder of the party to Salt Lake City, where public opinion was ready to charge the Mormons with the murder. Beckwith believed this to be entirely false and used the friendly assistance of Brigham Young, who persuaded the tribe’s chiefs to return the instruments and records stolen from the party.

The route surveyed by Captain Gunnison passed around the northern end of the ravine of the Colorado River, which almost completely separates the Southwest from the United States. Farther south, within the United States, there were only two available points at which railways could cross the canyon, at Fort Yuma and near the Mojave River. Towards these crossings, the 35th and 32nd parallel surveys were directed.

Second only to Governor Stevens’s in its extent was the exploration conducted by Lieutenant Amiel W. Whipple from Fort Smith, Arkansas, on the Arkansas River to Los Angeles, California, along the 35th parallel. Like Governor Stevens, this route was not the channel of regular traffic, although later, it was meant to have some share in the organized overland commerce. Here was also found a line that contained only two or three serious obstacles to be overcome. Whipple’s instructions planned for him to begin his observations at the Mississippi River. He believed that the navigable Arkansas River and the railways already projected in that state made it needless to commence farther east than Fort Smith, on the edge of the Indian Country. He began his survey on July 14, 1853. His westward march was for two months up the right bank of the Canadian River, as it traversed the Choctaw and Chickasaw reserves, to the 100th meridian, where it emerged from the panhandle of Texas, and across the panhandle into New Mexico. After crossing the upper waters of the Pecos River, he reached the Rio Grande at Albuquerque, New Mexico, where his party tarried for a month or more, working over their observations, making local explorations, and sending back to Washington an account of their proceedings thus far. Towards mid-November, they started toward the Colorado Chiquita and the Bill Williams Fork, through “a region over which no white man is supposed to have passed.” The severest difficulties of the trip were found near the valley of the Colorado River, which was entered at the junction of the Bill Williams Fork and followed north for several days. A crossing here was made near the supposed mouth of the Mojave River at a place where porphyritic and trap dykes, outcropping, gave rise to the name of the Needles, California. The river was crossed on February 27, 1854, three weeks before the party reached Los Angeles.

South of the route of Lieutenant Whipple, the 32nd parallel survey was run to the Fort Yuma crossing of the Colorado River. No attempt was made in this case at a comprehensive survey under a single leader. Instead, the section from the Rio Grande at El Paso to the Red River at Preston, Texas, was run by John Pope, brevet captain in the topographical engineers, in the spring of 1854. Lieutenant J. G. Parke carried the line simultaneously from the Pima villages on the Gila River to the Rio Grande. A survey made by Lieutenant-colonel Emory in 1847 was drawn west of the Pima villages to the Colorado River. The lines in California were surveyed by yet a different party. Here again, an accessible route was discovered. Within the states of California and Oregon, various connecting lines were surveyed by parties under Lieutenant R.S. Williamson in 1855.

The evidence accumulated by the Pacific railway surveys began to pour in upon the War Department in the spring of 1854. Partial reports, at first, elaborate and minute scientific articles, followed later, made up a series that filled the twelve enormous volumes of published papers by the close of the decade. Rarely have efforts so great accomplished so little in the way of actual contribution to knowledge. The chief importance of the surveys was in proving by scientific observation what was already commonplace among laymen—that the continent was traversable in many places and that the incidental problems of railway construction were in finance rather than in engineering. The engineers stood ready to build the road any time and almost anywhere.

The Secretary of War submitted to Congress the first installment of his report under the resolution of March 3, 1853, on February 27, 1855. The labors of compilation and examination of the field manuscripts were not completed, but he could make general statements about the probability of success. At five points, the continental divide had been crossed; over four of these railways were entirely practicable, although the shortest routes to San Francisco, California, ran by the one pass, Cochetopa, where it would be unreasonable to construct a road.

Secretary Davis recommended one of the routes surveyed as “the most practicable and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean.” In all cases, cost, speed of construction, and ease of operation needed to be ascertained and compared. The estimates guessed at by the parties in the field and revised by the War Department pointed to the southernmost as the most desirable route. To reach this conclusion, it was necessary to accuse Governor Stevens of underestimating the cost of labor along his northern line, but the figures were conclusive. On this 32nd parallel route, the Secretary of War declared, “the progress of the work will be regulated chiefly by the speed with which cross-ties and rails can be delivered and laid… The few difficult points… would delay the work but an inconsiderable period… The climate on this route is such as to cause less interruption to the work than on any other route. This is the shortest and least costly route to the Pacific and the shortest and cheapest route to San Francisco, the greatest commercial city on our western coast. At the same time, the aggregate length of railroad lines connecting it at its eastern terminus with the Atlantic and Gulf seaports is less than the aggregate connection with any other route.”

The Pacific railway surveys were ordered as Congress’s only step in its deadlock situation. Senator Gwin had long ago told his fears that the advocates of the disappointed routes would unite to hinder the fortunate one. To the South, as to Jefferson Davis, Secretary of War, the 32nd parallel route was satisfactory, but there was as little chance of building a railway as in 1850. The railways’ discussion might be founded upon facts rather than hopes and fears in the coming days. Still, either unanimity or compromise would be possible in a reasonably remote future. The overland traffic, which was assuming great volume as the surveys progressed, had yet nearly 15 years before the railway should drive it out of existence. And no railway could even be started before the war had removed one of the contesting sections from the floor of Congress.

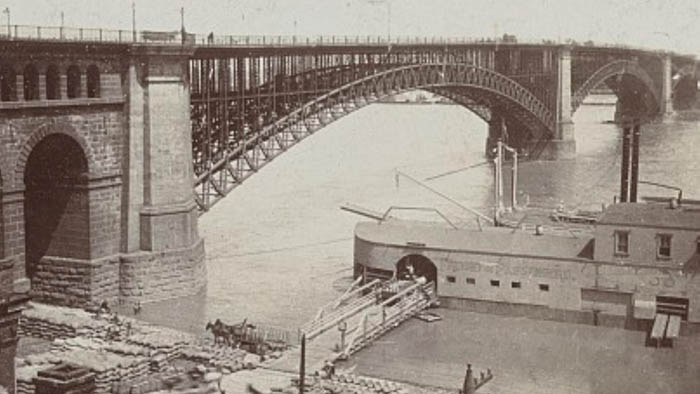

Yet in the years since Asa Whitney began his agitation, the railways of the East had constantly expanded. When Jefferson Davis reported in 1855, the first bridge to cross the Mississippi River was under construction in St. Louis, Missouri, and the Illinois Central Railroad was opened in 1856. When the Civil War began, the railway frontier coincided with the agricultural frontier, and both were ready to span the gap that separated them from the Pacific.

Source: Paxson, Frederic L.; Last American Frontier, The MacMillan Company, New York, 1910. The text as it appears here is not verbatim, as it has been edited for clarity and ease for the modern reader. Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, April 2024.

Also See:

A Century of Railroad Building