In 1821, the land beyond Missouri was a vast uncharted region called home to great buffalo herds and unhappy Indians, angered over the continual westward expansion of the white man. Before Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, the Spanish banned trade between Santa Fe and the United States. After independence, Mexico encouraged trade. Though numerous dangers awaited him, Captain William Becknell was determined to travel through waterless plains and warlike Indians to trade with the distant Mexicans in New Mexico.

Santa Fe Trail:

Santa Fe Trail Summary Description (See Below)

Santa Fe Trail Detail & Timeline

Trail Routes

Santa Fe Trail Through Missouri

Jornada Del Muerto on the Cimarron Route of the Santa Fe Trail, photo courtesy National Park Service.

Granada-Fort Union Military Road

Stories:

Civil War on the Santa Fe Trail: 1861-1865

Early Traders on the Santa Fe Trail

Famous Men of the Santa Fe Trail

Fighting the Comanche on the Santa Fe Trail

Heroes of the Old Santa Fe Trail

International Trade on the Santa Fe Trail, 1821-1846

The End of the Santa Fe Trail by Gerald Cassidy, about 1910

Indian Terrors on the Santa Fe Trail

The Life & Mysterious Death of Samuel B. Watrous

The Mexican War and the Santa Fe Trail, 1846-1848

Overland Mail on the Santa Fe Trail

Railroad Building on the Santa Fe Trail

The Santa Fe Trail and the Railroad: 1865-1880

Santa Fe Trail – Exploration & Illegal Trade – Pre-1821

Stories of the Old Santa Fe Trail

Santa Fe Trail Summary:

Wagon Train on the Santa Fe Trail

On September 1, 1821, Willliam Becknell left Franklin, Missouri, with four trusted companions. After arriving in Santa Fe on November 16 and making an enormous profit, he made plans to return, thus blazing the path that would become known as the Santa Fe Trail.

On his first trip, Becknell loaded manufactured goods from Missouri onto a mule train to trade for furs, gold, silver, and other goods in New Mexico. However, Becknell had found a passable wagon route by his third trip, thus beginning the many wagon trains heading to the southwest. Credited as the “Father of the Santa Fe Trail,” Becknell continued to make multiple trips along the trail, profiting enormously on his daring travels. Soon, many traders, as well as the military, were traveling the route.

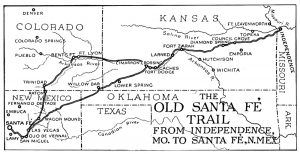

Two routes soon developed along the trail, the Mountain Route and the Cimarron Route, also called the Jornada Route. Both routes followed the same path from Missouri, traveling west to the Arkansas River and following the river into southwest Kansas. For many years, the only trading post between Independence, Missouri, and Santa Fe, New Mexico, was in Council Grove, Kansas, some 130 miles from Independence and over 650 miles from Santa Fe.

At Fort Larned, Kansas, the trail split into two branches. The Mountain Route was longer but not quite as dangerous, with fewer warlike Indians and more water along the route. This branch traveled about 230 miles between Fort Larned and Bent’s Fort near present-day La Junta, Colorado, following the Arkansas River before turning south through the Raton Pass to Santa Fe.

Though the shorter Jornada Route, also called the Cimarron Cutoff, provided less water, it saved the travelers ten days by cutting southwest across the Cimarron Desert to Santa Fe. The Cimarron Desert route was shorter and more accessible for wagon parties than the mountainous Raton Pass, but travelers risked attacks by Native Americans in addition to water shortages. Despite the hazards, the shorter route would carry 75% of the Santa Fe Trail pioneers.

In 1825, the United States obtained a right of way from the Osage Indians, officially establishing the Santa Fe Trail as a national “highway.” In 1827, Independence, Missouri, was founded and, within a few years, became the major outfitting point on the eastern end of the trail.

In 1834, Bent’s Fort, a fur trade post on the upper Arkansas River, was established near La Junta, Colorado. William and Charles Bent, Ceran St. Vrain and Company led a party and wagons eastbound from Santa Fe, New Mexico, in the late summer, traveled by way of Taos and Raton Pass to Bent’s Fort; then came down the Arkansas River to the Santa Fe Trail, opening the Bent’s Fort Santa Fe Trail.

By this time, the trail was frequently used with more than 2000 wagons, in caravans of about 50 departing each spring from Missouri. Travel and trading along the trail were restricted when the Mexican-American War began. However, the military heavily used it to transport supplies from the Missouri River towns to the Southwest. Trading resumed when the war ended in 1848, and considerable military freight was hauled over the trail to supply the southwestern forts.

In 1849, with the discovery of gold in California, westbound emigrants, in increasing numbers, traveled the Santa Fe Trail to Bent’s Fort, then journeyed northward by a trail along the base of the Rocky Mountains to Fort Laramie and beyond. By 1850, a monthly stagecoach line was established between Independence, Missouri, and Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Trade was limited again during the Civil War (1861-1865), but by the late 1860s, activity along the trail had resumed. In 1880 a railroad reached Santa Fe, and the use of the Santa Fe Trail declined.

Other trails connecting to the Santa Fe Trail included the Old Spanish Trail, which linked Santa Fe to Los Angeles, and the El Camino Real, which connected Santa Fe to Mexico City.

Today, part of the route has been designated a National Scenic Byway.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2023.

Also See:

Early Transportation on the Great Plains

Tales & Trails of the American Frontier

Source: See Santa Fe Trail Writing Credits