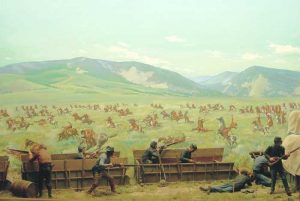

The crisis in the struggle for control of the Great Plains may be said to have been reached about the time of the Fetterman Massacre at Fort Phil Kearny, Wyoming, in 1866.

During the previous 15 years, the causes had been shaped through the development and use of trails, the opening of the mining territories, and the agitation for a continental railway. Now, the railroad was not only authorized and begun, but Congress had put a premium upon its completion by an act of July 1866, which permitted the Union Pacific Railroad to build west and the Central Pacific Railroad to build east until the two lines met. In the ensuing race for the land grants, the roads were pushed with new intensity so that the crisis of the Indian problem was speedily reached. In the fall of 1866, Ben Holladay saw the end of the overland freighting and sold out. In November, the terminus of the overland mail route was moved west to Fort Kearney, Nebraska, where the Union Pacific had arrived in its course of construction.

As the crisis drew near, radical differences of opinion among those who must handle the tribes became apparent. The question of the management by the War Department or the Interior was in the air and was raised repeatedly in Congress. More fundamental was the question of policy, upon which the view of Senator John Sherman was as clear as any.

“I agree with you,” he wrote to his brother William in 1867, “that Indian wars will not cease until all the Indian tribes are absorbed in our population and can be controlled by constables instead of soldiers.”

Upon another phase of management, Francis A. Walker wrote a little later: “There can be no question of national dignity involved in the treatment of savages by a civilized power. The proudest Anglo-Saxon will climb a tree with a bear behind him… With wild men, as with wild beasts, the question of whether to fight, coax, or run is a question merely of what is safest or easiest in the situation given.” That responsibility for some decided action lay heavily upon the whites may be implied from the admission of Colonel Henry Inman, who knew the frontier well—” that, during more than a third of a century passed on the plains and in the mountains, he has never known of a war with the hostile tribes that was not caused by broken faith on the part of the United States or its agents.” A professional Indian fighter, like Kit Carson, declared on oath that “as a general thing, the difficulties arise from aggressions on the part of the whites.”

In Congress, all the interests involved in the Indian problem found spokesmen. The War and Interior departments had ample representation; the Western members commonly voiced the extreme opinion of the frontier; Eastern men often spoke for the humanitarian sentiment that saw much good in the Indian and much evil in his treatment. However, Congress felt it lacked information regarding special action. The departments best informed were partisan and antagonistic. It was a matter of high critical scholarship to determine, with the passions cooled off, truth and responsibility in such affairs as the Dakota Uprising in Minnesota, the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado, or the Fetterman Massacre.

To lighten in part its feeling of helplessness amid interested parties, Congress raised a committee of seven, three of the Senate and four of the House, in March 1865, to investigate and report on the condition of the Indian tribes. The joint committee was resolved upon during a bitter and ill-informed debate on Colonel John Chivington; while it sat, the Cheyenne War ended, and the Sioux War broke out; the committee reported in January 1867. To facilitate its investigation, it divided itself into three groups to visit the Pacific Slope, the Southern Plains, and the Northern Plains. Its report, with the accompanying testimony, filled over 500 pages. In all the storm centers of the Indian West, the committee sat, listened, and questioned.

The Report on the Condition of the Indian Tribes gave a sad view of the future from the Indians‘ standpoint. General John Pope was quoted to the effect that they were rapidly dying off from wars, cruel treatment, unwise policy, and dishonest administration, “and by steady and resistless encroachments of the white emigration towards the west, which is every day confining the Indians to narrower limits, and driving off or killing the game, their only means of subsistence.” To this catalog of causes, General James Carleton, who must have believed his war of Apache and Navajo extermination a potent handmaid of providence, added: “The causes which the Almighty originates, when in their appointed time He wills that one race of man—as in races of lower animals—shall disappear off the face of the earth and give place to another race, and so on, in the great cycle traced out by Himself, which may be seen, but has reasons too deep to be fathomed by us. The races of mammoths, mastodons, and the great sloths came and passed away; the red man of America is passing away!”

The committee believed that the wars, with their incidents of slaughter and extermination by both sides, were generally the result of white encroachments. It did not fall in with the growing opinion that the control of the tribes should be passed over to the War Department. Still, it recommended a system of visiting boards, each including a civilian, a soldier, and an Assistant Indian Commissioner, for the regular inspection of the tribes. The committee’s recommendation came to nothing in Congress. Still, the information it gathered, supplementing the annual reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and the special investigations of single wars, gave much additional weight to the belief that a crisis was at hand.

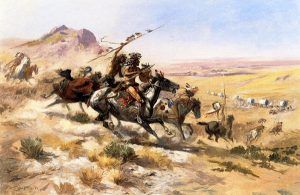

In the meantime, the Cheyenne and Sioux wars dragged on through 1866 and 1867. The Powder River country continued to be a battlefield, with Captain James Powell’s Wagon Box Fight coming in the summer of 1867. In the spring of 1867, General Hancock destroyed a Cheyenne village at Pawnee Fork. Eastern opinion came to demand more forcefully that this fighting should stop. Western opinion was equally insistent that the Indians must go. At the same time, General William Sherman believed that a part of its belligerent demand was due to a desire for “the profit resulting from military occupation.” Sure it was that war had lasted for several years with no definite results, save to rouse the passions of the West, the revenge of the Indians, and the philanthropy of the East. The army had had its chance. Now, the time had come for general, genuine attempts at peace.

The 40th Congress, beginning its life on March 4, 1867, actually began its session at that time. Ordinarily, it would have waited until December, but the prevailing distrust of President Andrew Johnson and his Reconstruction ideas induced it to convene as early as the law allowed. Among the most significant of its measures in this extra session was “Mr. Henderson’s bill for establishing peace with certain Indian tribes now at war with the United States,” which, in the view of the Nation, was a “practical measure for the security of travel through the territories and for the selection of a new area sufficient to contain all the unsettled tribes east of the Rocky Mountains.”

Senator Sherman had informed his brother of the prospect of this law, and the General had replied: “The fact is, this contact of the two races has caused universal hostility, and the Indians operate in small, scattered bands, avoiding the posts and well-guarded trains and hitting little parties who are off their guard. I have a much heavier force on the plains. Still, they are so large that it is impossible to guard at all points, and the clamor for protection everywhere has prevented our being able to collect a large force to go into the country where we believe the Indians have hidden their families, up the Yellowstone River and down on the Red River.”

Sherman believed more in fighting than in treating at this time, yet he went on the commission erected by the act of July 20, 1867. By this law, four civilians, including the Indian Commissioner and three generals of the army, were appointed to collect and deal with the hostile tribes, with three chief objectives in view: to remove the existing causes of complaint, to secure the safety of the various continental railways and the overland routes, and to work out some means for promoting Indian civilization without impeding the advance of the United States. To this end, they were to hunt for permanent homes for the tribes, which were to be off the railroad lines of all the then chartered—the Union Pacific, the Northern Pacific, and the Atlantic and Pacific.

The Peace Commission, thus organized, sat for 15 months. When it finally rose, it had opened the way for the railways, so far as treaties could avail. It had persuaded many tribes to accept new and more remote reserves. Still, in its debates and negotiations, the breach between military and civil control had widened, so the Commission was ultimately divided against itself.

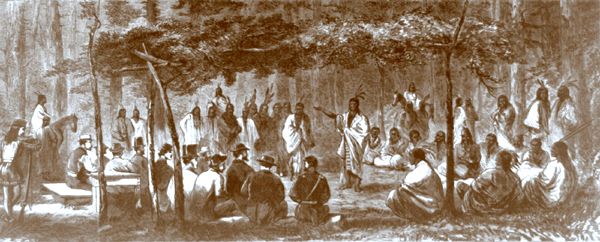

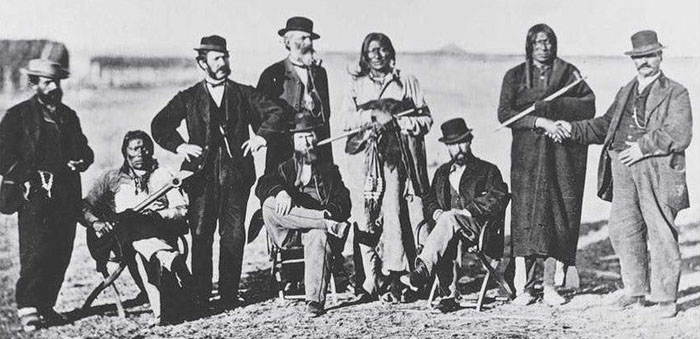

Peace Commission, 1867.

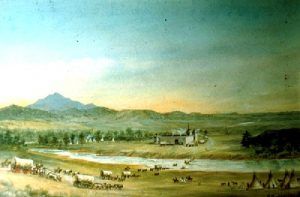

On August 6, 1867, the Commission organized at St. Louis, Missouri, and discussed plans to contact the tribes with whom it had to treat. “The first difficulty presenting itself was to secure an interview with the chiefs and leading warriors of these hostile tribes. They were roaming over an immense country, thousands of miles in extent, much of it unknown even to hunters and trappers of the white race. Small war parties constantly emerging from this vast extent of the unexplored country would suddenly strike the border settlements, killing the men and carrying off into captivity the women and children. Companies of workmen on the railroads, at points hundreds of miles from each other, would be attacked on the same day, perhaps in the same hour. Overland mail coaches could not be run without military escort, and railroad and mail stations unguarded by soldiery were in perpetual danger. All safe transit across the plains had ceased. To go without soldiers was extremely hazardous; to go with them forbade reasonable hope of securing peaceful interviews with the enemy.” Fortunately, the Peace Commission contained within itself the most useful of assistants. General William Sherman and Commissioner Taylor sent out word to the Indians through the military posts and Indian agencies, notifying the tribes that the Commissioners desired to confer with them near Fort Laramie, Wyoming, in September and Fort Larned, Kansas, in October.

The Fort Laramie conference bore no fruit during the summer of 1867. After inspecting conditions on the upper Missouri River, the Commissioners proceeded to Omaha, Nebraska, in September and then to North Platte station on the Union Pacific Railroad. They met Swift Bear of the Brule Sioux and learned that the Sioux would not be ready to meet them until November. The Powder River War was still fought by chiefs who could not be reached quickly and whose delegations must be delayed. When the Commissioners returned to Fort Laramie in November, they found matters a little better. Chief Red Cloud, who was the recognized leader of the Oglala and Brule Sioux and the hostile northern Cheyenne, refused even to see the envoys and sent them word: “that his war against the whites was to save the valley of the Powder River, the only hunting ground left to his nation, from our intrusion. He assured us that whenever the military garrisons at Fort Philip Kearney and Fort C. F. Smith were withdrawn, the war on his part would cease.” Regretfully, the Commissioners left Fort Laramie, having seen no savages except a few non-hostile Crow, and having summoned Red Cloud to meet them during the following summer, after asking “a truce or cessation of hostilities until the council could be held.”

The southern plains tribes were met at Medicine Lodge Creek, some 80 miles south of the Arkansas River. Before the Commissioners arrived here, General Sherman was summoned to Washington, his place taken by General C.C. Augur, whose name makes the eighth signature to the published report. For some time after the Commissioners arrived, the Cheyenne, sullen and suspicious, remained in their camp 40 miles away from Medicine Lodge, Kansas. But the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache agreed, while the others held off. On October 21, these ceded all their rights to occupy their outstanding claims in the Southwest, the whole of the two panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma and agreed to confine themselves to a new reserve in the southwestern part of Indian Territory between the Red River and the Washita River, on lands taken from the Choctaw and Chickasaw in 1866.

The Commissioners could not greatly blame the Arapaho and Cheyenne for their reluctance. These had accepted in 1861 the triangular Sand Creek reserve in Colorado, where they had been massacred by Colonel Chivington in 1864. Whether rightly or not, they believed themselves betrayed, and the Indian Office sided with them. In 1865, after Sand Creek, they exchanged this tract for a new one in Kansas and Indian Territory, which was amended to nothingness when the Senate added to the treaty the words, “no part of the reservation shall be within the state of Kansas.” They had left the former reserve; the new one had not been given to them, yet for two years after 1865, they had generally kept the peace. Sherman traveled through this country in the autumn of 1866 and “met no trouble whatever,” although he heard rumors of Indian wars. In 1867, General Winfield Scott Hancock had destroyed one of their villages on the Pawnee Fork of the Arkansas River without provocation, the Indians believed. After this, there had been admitted war. The Indians had been on the warpath all the time, plundering the frontier and dodging the military parties. They could not realize that the Peace Commissioners offered a policy change for some weeks. Yet finally, these yielded to blandishment and overture and signed, on October 28, a treaty at Medicine Lodge. The new reserve was a bit of barren land nearly destitute of wood and water and containing many streams that were either salty or dry during most of the year. It was in the Cherokee Outlet, between the Arkansas and Cimarron Rivers.

The Medicine Lodge treaties were the chief result of the summer’s negotiations. The Peace Commission returned to Fort Laramie the following spring to meet the reluctant northern tribes. The Sioux, the Crow, and the Arapaho and Cheyenne allied with them and made peace after the Commissioners had assented to the terms laid down by Red Cloud in 1867. They had convinced themselves that the occupation of the Powder River Valley was both illegal and unjust, and accordingly, the garrisons had been drawn out of the new forts. Much to the anger of Montana was this yielding. “With characteristic pusillanimity,” wrote one of the pioneers, years later, denouncing the act, “the government ordered all the forts abandoned and the road closed to travel.” In the new Fort Laramie treaty of April 29, 1868, it was explicitly agreed that the country east of the Big Horn Mountains was to be considered as unceded Indian territory, while the Sioux bound themselves to occupy as their permanent home the lands west of the Missouri River — an area coinciding to-day with the western end of South Dakota. Thus began the actual compression of the Sioux of the plains.

The treaties made by the Peace Commissioners were the most important but were not the only treaties of 1867 and 1868, looking towards the relinquishment by the Indians of lands along the railroad’s right of way. It had been found that transit rights through the Indian Country, such as those secured at Laramie in 1851, were insufficient. The Indian must leave even the vicinity of the travel route for peace and his own good.

Most important of the other tribes shoved away from the route were the Ute, Shoshone, and Bannock, whose country lay across the great trail just west of the Rocky Mountains. The Ute, having given their name to the territory of Utah, were to be found south of the trail, between it and the lower waters of the Colorado River. Their western bands were earliest in negotiation and were settled on reserves, the most important being on the Uintah River in northeast Utah after 1861. The Colorado Ute began to treat in 1863 but did not make definite sessions until 1868 when the southwestern third of Colorado was set apart for them. At the start, active life in Colorado territory was confined to the mountains near Denver, while the Indians were pushed down the slopes of the range on both sides. But as the eastern Sand Creek reserve soon had to be abolished, so Colorado began to growl at the western Ute reserve and to complain that indolent savages were given better treatment than white citizens. The Shoshone and Bannock ranged from Fort Hall, Idaho, to the north and were visited by General Augur at Fort Bridger in the summer of 1868. As a result of his gifts and diplomacy, the former were pushed up to the Wind River reserve in Wyoming territory, while the latter was granted a home around Fort Hall, Idaho.

The friction with the Indians was heaviest near the line of the old Indian frontier and tended to be lighter towards the west. It was natural enough that on the eastern edge of the plains, where the tribes had been colonized and where the Indian population was most dense, the difficulties should be most significant. Indeed, the only wars that were sufficiently important to count as resistance to the westward movement were those of the plains tribes and were fought east of the continental divide. The mountain and western wars were episodes isolated from the main movements. Yet these great plains that now had to be abandoned had been set aside as a permanent home for the race in pursuance of Monroe’s policy. In the report of the Peace Commissioners, all agreed that the time had come to change it.

The influence of the humanitarians dominated the Commissioners’ report, which was signed in January 1868. Wherever possible, the side of the Indian was taken. The Chivington massacre was an “indiscriminate slaughter,” scarcely paralleled in the “records of the Indian barbarity”; General Hancock had ruthlessly destroyed the Cheyenne at Pawnee Fork, though himself in doubt as to the existence of a war: Fetterman had been killed because “the civil and military departments of our government cannot, or will not, understand each other.” Apologies were made for Indian hostility, and the “revolting” history of the removal policy was described. It was the result of this policy that promoted barbarism rather than civilization. “But one thing then remains to be done with honor to the nation, and that is to select a district, or districts of the country, as indicated by Congress, on which all the tribes east of the Rocky Mountains may be gathered. Each district should have a territorial government with powers adapted to the designed ends. The governor should be a man of unquestioned integrity and purity of character; he should be paid a salary to place him above temptation.” He should be given adequate powers to keep the peace and enforce a policy of progressive civilization. This report of the Peace Commissioners confirmed the belief that under American conditions, the Indian problem was insoluble, well-informed, and philanthropic as they were. After they condemned an existing removal policy, the only remedy they could offer was another policy of concentration and removal.

Cheyenne and Lakota warriors ride out to meet Hancock’s forces as they approach the Indian village by Jerry Thomas.

The Commissioners recommended that the Indians be colonized on two reserves, north and south of the railway lines. The southern reserve was the old territory of the civilized tribes, known as Indian Territory, where the Commissioners thought 86,000 could be settled within a few years. A northern district might be located north of Nebraska, within the area they later allotted to the Sioux; 54,000 could be colonized here. Individual Indians might be allowed to own land and be incorporated among the citizens of the Western states. Still, most of the tribes ought to be settled in the two Indian territories, while this removal policy should be the last.

Upon the question of civilian or military control, the Commissioners were divided. They believed that the War and Interior departments were too busy to give proper attention to the wards and recommended an independent department for the Indians. In October 1868, they reversed this report and, under military influence, spoke strongly about incorporating the Indian Office in the War Department. “We have now selected and provided reservations for all, off the great roads,” wrote General Sherman to his brother in September 1868. “All who cling to their old hunting grounds are hostile and will remain so till killed off. We will have a sort of predatory war for years, now and then be shocked by the indiscriminate murder of travelers and settlers, but the country is so large, and the advantage of the Indians so great, that we cannot make a single war and end it. From the nature of things, we must take chances and clean out Indians as we encounter them.” Although military control tended to provoke Indian wars, the army was near the truth in its notion that Indians and whites could not live together.

These treaties of 1867 and 1868 opened the way across the continent, and the Union Pacific hurried to take advantage of it. The other Pacific railways, Northern Pacific, Atlantic, and Pacific, were so slow in using their charters that hope in their construction was nearly abandoned. Still, the chief enterprise neared completion before the inauguration of President Grant. The new territory of Wyoming, rather than the statue of Columbus which Benton had foreseen, was perched upon the summit of the Rockies as its monument.

Intelligent easterners had difficulty keeping pace with western development during the decade of the Civil War. The United States itself had made no codification of Indian treaties since 1837 and allowed the law of tribal relations to remain scattered through a thousand volumes of government documents. Even Indian agents and army officers were often as ignorant of the facts as the general public. “All Americans have some knowledge of the country west of the Mississippi,” lamented the Nation in 1868, but “there is no book of travel relating to those regions which do more than add to a mass of desultory information. Few men have more than the most unconnected and unmethodical knowledge of the vast territory beyond Kansas… By this time, Leavenworth must have ceased to be in the West; probably, as we write, Denver has become an Eastern city, and day by day, the Pacific Railroad is abolishing the marks distinguishing Western from Eastern life… A man talks to us of the country west of the Rocky Mountains, and while he is talking, the Territory of Wyoming is established, which neither he nor his auditors have heard before.”

In that division of the plains, which was sketched out in the 1850s, Kansas and Nebraska’s great unstructured eastern territories met on the summit of the Rocky Mountains, the great western territories of Washington, Utah, and New Mexico. The gold booms had broken up all of these. Arizona, Nevada, Idaho, Montana, Dakota, and Colorado had found their excuses for existence, while Kansas and Nevada entered the Union, with Nebraska following in 1867. Between the 37th and 41st parallels, Colorado fairly straddled the divide. To the north, in the region of the great river valleys—Green, Big Horn, Powder, Platte, and Sweetwater—the precious metals were not found in quantities that justified exploitation earlier than 1867. But that year, moderate discoveries on the Sweetwater and the arrival of the terminal camps of the Union Pacific made a scheme for a new territory plausible.

Without causing any great excitement, the Sweetwater mines brought a few hundred men to the vicinity of South Pass, Wyoming. A handful of towns was established, a county was organized, a newspaper was brought into life at Fort Bridger. If the railway had not appeared simultaneously, the foundation for a territory would probably have been too slight. But the Union Pacific, which had ended at Julesburg, Colorado, early in 1867, extended its terminus to a new town, Cheyenne, in the summer and to Laramie City in the spring of 1868.

Cheyenne was laid out a few weeks before the Union Pacific Railroad advanced to its site. It had a better prospect of life than most of the mushroom cities that accompanied the westward course of the railroad because it was the natural junction point for the Denver trade. Colorado had been much disappointed at its failure to induce the Union Pacific managers to put Denver on the main line of the road. It felt injured when compelled to do its business through Cheyenne. But just because of this, Cheyenne grew in the autumn of 1867 with a rapidity unusual even in the West. It was not an orderly or reputable population that it had during the first months of its existence, but, to its good fortune, the advance of the road to Laramie drew off the worst of the floating inhabitants early in 1868. Cheyenne was left with an overlarge town site but with some real excuse for existence. Most of the terminal towns vanished completely when the railroad moved on.

A new territory for the country north of Colorado had been talked about as early as 1861. Since the creation of Montana Territory in 1864, this area had been attached, obviously only temporarily, to Dakota. With the influence of the mining and railways at work, the population appealed to the Dakota legislature and Congress for independence. Congress created the new territory in July 1868. It was called Wyoming, just escaping the names of Lincoln and Cheyenne.

For several years after the Sioux treaties of 1868 and the erection of Wyoming Territory, the Indians of the northern plains kept the peace. The travel routes had been opened, the white claim to the Powder River Valley had been surrendered, and a great northern reserve had been created in the Black Hills country of southern Dakota. Lessening contact removed the danger of Indian friction. But the southern tribes were still uneasy—treacherous or ill-treated, according as the sources vary—and one more war was needed before they could be compelled to settle down.

Source: Paxson, Frederic L.; Last American Frontier, The MacMillan Company, New York, 1910. Compiled by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, April 2024.

Also See:

Indian Troubles During Construction of the Railroad