by Frank W. Blackmar, 1912

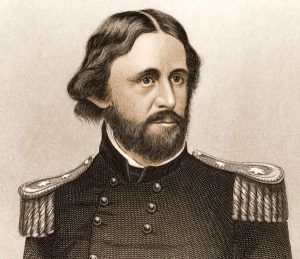

The explorations of John Charles Fremont, made under an act of Congress, were important in placing an accurate description of the region west of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers before the people.

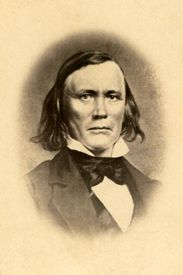

His first expedition was made in 1842 with only 21 men from the St. Louis, Missouri area, principally Creole and Canadian voyageurs who had become familiar with prairie life in the service of the fur companies in the Indian country. Charles Preuss, a native of Germany, was his assistant in the topographical part of the survey; Lucien B. Maxwell of Kaskaskia, Illinois, was engaged as a hunter, and Christopher “Kit” Carson was the guide.

From St. Louis, the party proceeded to Cyprian Chouteau’s trading house on the Kansas River, about 10 miles west of the Missouri state line. They left on June 10, 1842, and after traveling about ten miles, they reached the Santa Fe Trail, upon which they continued for a short time.

After traveling about 11 miles, they encamped early on a small stream before continuing along the Santa Fe Road, before camping on a small creek called by the Indians, Mishmagwi. On June 12, the party seems to have camped near the site of what would later become Lawrence, for, in Colonel Fremont’s narrative, he said:

“We encamped in a remarkably beautiful situation on the Kansas bluffs, which commanded a fine view of the river valley, here from 3 to 4 miles wide. The central portion was occupied by a broad belt of heavy timber, and nearer the hills, the prairies were of the richest verdure [rich green vegetation].“

On the 14th, he crossed to the north side of the river, probably near where Topeka, Kansas, is now located. On the 16th, he said:

“We are now fairly in the Indian country, and it began to be time to prepare for the chances of the wilderness.“

The party continued its journey along the foothills of the Kansas Valley and on the 20th, crossed the Black Vermillion River, “which has a rich bottom of about one mile in breadth, one-third of which is occupied by timber.” After a day’s march of 24 miles, they reached the Big Blue River and encamped on the uplands of the western side, near a small creek, where there was a fine large spring of frigid water. At noon on the 22nd, a halt was made at Wyeth’s Creek, in the bed of which were numerous boulders of dark, ferruginous sandstone, mingled with others of the red sandstone variety. At the close of the same day, they made their bivouac in the midst of some well-timbered ravines near the Little Blue River, 24 miles from their camp of the preceding night. Crossing the next morning several handsome creeks, with water clear and sandy beds, at 10 a.m., they reached a beautifully wooded stream, about 35 feet wide, called Sandy Creek and, as the Otoe Indians frequently wintered there, was also called Otoe Fork. After another hard day’s march of 28 miles, they encamped on the Little Blue River. Then their route lay up the valley, and on the night of the 25th, they halted at a point in what is now Nuckolls County, Nebraska.

At this time, Fremont wrote:

“From the mouth of the Kansas River, according to our reckoning, we had traveled 328 miles, and the geological formation of the country we had passed over consisted of lime and sandstone, covered by the same erratic deposits of sand and gravel which forms the surface rock of the prairies between the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers.”

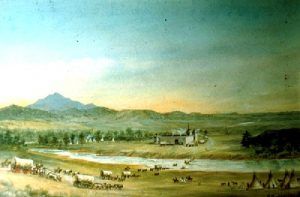

They then marched up the Platte Valley, but upon reaching the forks, the main party was sent up the north fork while a few men under Fremont passed up the south fork to St. Vrain’s Fort, Colorado. From here, they marched northward to the north fork and joined the main body at Fort Laramie, Wyoming. Although the Indians were on the warpath farther up the river, Fremont determined to proceed. They continued to advance without serious interruption, arrived at the Sweetwater River, marched through South Pass, Wyoming, and ascended the highest peak of the Wind River Mountains. The return journey down the Platte River was made without notable incident.

Fremont’s second exploration was made in 1843, his party consisting principally of Creole and Canadian French and Americans, amounting to 39 men.

To make the exploration as useful as possible, Colonel Fremont determined to vary the route to the Rocky Mountains from what he had followed in 1842. Instead, he decided upon a route up the valley of the Kansas River to the head of the Arkansas River and a pass in the mountains, if any could be found, at the sources of that river. By making this deviation, the problem of a new road to Oregon and California might be found with a better climate and more knowledge obtained of an important river and the country it drained.

The departure was made from what is now Kansas City, Kansas, on the morning of May 29, 1843, and at the close of that day, the party encamped about four miles beyond the frontier, on the verge of the great prairies. Resuming their journey on the 31st, they encamped in the evening at Elm Grove and, from then until June 3, followed the same route as the expedition of 1842. Reaching the ford of the Kansas River, near the present site of Lawrence, they left the usual emigrant road to the mountains and continued their route along the south side of the river, where their progress was much delayed by numerous small streams, which required them to build frequent bridges. On the morning of June 4, they crossed Otter Creek and on the 8th, arrived at the mouth of Smoky Hill Fork, forming its junction with the Republican and Kansas Rivers. On the 11th, they resumed their journey along the Republican Fork and for several days continued to travel through a country beautifully watered with numerous streams, handsomely timbered, at which time Fremont would say:

“rarely an incident occurred to vary the monotonous resemblance which one day on the prairies here bears to another, and which scarcely requires a particular description.”

They had been gradually and regularly ascending in their progress westward and on the evening of the 14th, were 265 miles by their traveling road from the mouth of the Kansas River. At this point, the party was divided, and on the 16th, Fremont, with 15 men, proceeded in advance, bearing a little out from the river. That night he encamped on Solomon’s Fork of the Smoky Hill River, along whose tributaries he continued to travel for several days. On the 19th, he crossed the Pawnee Road to the Arkansas River. On the afternoon of June 30, he found himself overlooking a valley where, about 10 miles distant, “the south fork of the Platte River was rolling magnificently along, swollen with the waters of the melting snows.”

Upon reaching St. Vrain’s Fort in Colorado, he concluded to remain for a considerable time to explore the surrounding country. Boiling Spring River was traversed, and the pueblo at or near its mouth was visited. From Fort St. Vrain, the main party marched straight to Fort Laramie, Wyoming, while the party under Fremont passed farther to the west, skirting the mountain and carefully examining the country. The two detachments met on the Sweetwater River and after marching through South Pass, continued to Fort Bridger before moving west down the Bear River Valley.

The expedition then marched to California and passed a considerable distance down the coast when it returned, reaching Colorado at Brown’s Hole. While in Colorado, Fremont explored the wonderful natural parks there. On his return, he passed down the Arkansas River, visiting the “pueblo” and Bent’s Fort, at which place he arrived on July 1, 1844. On the 5th, he resumed his journey down the Arkansas River, traveling along a broad wagon road.

Desiring to complete the examination of the Kansas River, he soon left the Arkansas River. He took a northeasterly direction across the elevated dividing grounds, which separate that river from the waters of the Platte River. On the 8th, he arrived at the head of a stream that proved to be the Smoky Hill Fork of the Kansas River. After having traveled directly along its banks for 290 miles, the expedition left the river, where it bore suddenly off in a northwesterly direction toward its junction with the Republican Fork of the Kansas River, and continued its easterly course for about 20 miles when it entered the wagon road from Santa Fe, New Mexico to Independence, Missouri. On the last day of July, Fremont again encamped at Kansas City, Kansas, after an absence of 14 months.

The third expedition under Fremont in 1845 comprised nearly 100 men, many of which included his old companions, such as Kit Carson, Alexis Godey, Dick Owens, and several experienced Delaware Indians. His favorite, Basil Lajeunesse, and Lieutenants James W. Abert and William G. Peck were with him. With this more significant force, he felt he could deal with any emergency. The plains were crossed without noteworthy incident, except for a scare from the Cheyenne, and on August 2, Bent’s Fort, Colorado, was reached. On the 16th, a group of about 60 men, mostly picked for their known qualities of courage, hardihood, and faithfulness, left Bent’s Fort and started on its journey. On the 20th, it encamped at the month of Boiling Springs River, and on the 26th, at the mouth of the great canyon of the Arkansas River.

On the night of September 2, it reached the remote headwaters of the Arkansas River. Two days later, Fremont passed across the divide into the Grand River Valley and camped on Piney River, where a good supply of fish was caught. The marvelous beauty of the surroundings was especially noted by the scientists accompanying the party. Continuing westward without noteworthy incident, the party reached the Great Salt Lake early in October, and after great hardships, they reached Sutter’s Fort in California in December. The following year Fremont assisted the Californians in gaining their independence from Mexico.

A fourth expedition commenced in 1848, taken at Fremont’s own expense, and found a passage to California from the east along the headwaters of the Rio Grande. This was later followed by the Southern Pacific Railroad. He also fitted out upon his account the fifth expedition in 1853, designed to perfect the results of the fourth, by fixing upon the best route for a national highway from the valley of the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean.

These expeditions involved great hardships, but every suffering was rewarded by marvelous disclosures of the geographical variety and wealth of the country through which they passed. Kansas and the regions to the west were almost unknown up to this time.

His report of the resources found attracted the attention of the people of the East. From the time of these explorations, he dated the rapid influx of immigrants into Kansas and the speedy settlement of the territory. Traversing the state as he did, his complete reports turned the tide of home-seekers in that direction from its eastern to its western boundary.

By Frank W. Blackmar, 1912 – Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2022.

Also See:

John C. Fremont – The Pathfinder

Charles Preuss – Mapping the Oregon Trail

Trappers, Traders & Pathfinders

About the Article: The majority of this historic text was published in Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History, Volume I; edited by Frank W. Blackmar, A.M. Ph. D.; Standard Publishing Company, Chicago, IL 1912. However, the text on this page is not verbatim, as additions, updates, and editing have occurred.