By Grace Raymond Hebard and Earl Alonzo Brininstool in 1922

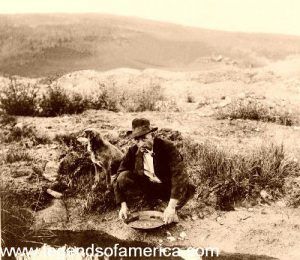

Gold was discovered in California during the days before railroads were established in the West and other localities, yielding enormous fortunes in the precious metal. During the summer of 1859, Colorado had 150,000 gold-seekers within its boundaries. This was largely a restless, floating population, one-third of which, in time, returned to the states, disgusted with the West and the mining districts within sight of Pike’s Peak.

Nevada, Idaho, and Montana proved rich fields for those who had become dissatisfied with other districts, and the trails to new mining camps were now filled with an eager crowd seeking new localities wherever there was a rumor of a great “strike.” There is no doubt that in time, the fields the prospector had left proved to be quite as rich in returns as the new locality, but the desire to acquire a vast fortune in a night was too much of a temptation to be overlooked.

Although Wyoming did not experience the intense and prolonged gold excitement as was felt in the territory outside of her boundaries, South Pass City, a few miles north of the famous South Pass, contributed materially to the total of gold mining in the 1860s. Gold in paying quantities was first discovered in this camp as early as 1842 by a member of the American Fur Company. However, no development was done until 1857, when 40 men prospected the entire length of the Sweetwater River. Gold was found everywhere in the stream and its numerous tributaries. In the fall of 1861, when gold was abundant in Colorado, Idaho, and Montana, three-score of men located claims along Willow Creek on which stream South Pass City was located. By 1863, mining was carried on in Carissa Gulch, and for decades, there were intermittent gold developments in this gulch.

At Fort Bridger, Wyoming, in August 1863, James Stuart found many teams there assembled to go to Bannack camp, having deserted the gold fields of Pike’s Peak. Among the disgruntled were many who tried their luck at South Pass City, as did hundreds of other miners from Montana, Colorado, Utah, Idaho, Nevada, and California. By 1868, this little hustling mining camp boasted more than 4,000 people, which greatly increased in the following year. All the roads in 1869 leading to South Pass City were full of eager, jostling prospectors. But the camp soon experienced a decline after the rich “pickings” had been mined. Today, South Pass City camp is a picturesque ghost town containing less than a score of people and a few relics in the way of log cabins of what was for several years the most prosperous mining camp in Wyoming.

The discovery of gold in southwestern Montana during the last days of 1862 gave rise to the city of Bannack, and by January 1863, it had a population of from 2,000 to 3,000 people. Bannack, for a short time, was the capital of the territory after it was organized in 1864, being moved to Virginia City when the scramble for gold was discovered in the new mining camp in Beaverhead Valley. Virginia City was first named “Varina” in honor of Mrs. Jefferson Davis, but the people of the camps soon changed the name to one that did not so constantly remind them of the South and the civil strife then being carried on in the States.

With the discovery of this new camp, the population of Bannack moved en masse to Virginia City, which, by 1864, had a population of 10,000 typical mining people. Virginia City remained the capital until 1866, when it was moved to Helena, another camp of unusual promise. Telegraph lines in 1866 were running to both camps by way of Salt Lake, and John Creighton operated this line as a branch of his mainline along the Oregon Trail. The number of letters sent from one of these western mining camps was evidence of the number of people in the camps. From Virginia City in 1863, 6,000 letters were dispatched to the east through Salt Lake, an accumulation of ten days when the stage was not in operation.

Helena, first called “Last Chance Gulch,” became a roaring camp in 1864 and soon became a shipping point for mining supplies. It was on a direct road from Fort Benton to Virginia City, and Bannack was 140 miles from the fort and 125 miles from Virginia City. The road between Helena and Fort Benton was on the west side of the Missouri River and easy to travel, though there was a trail through the mountains on the east side of the river.

The class of people who came to Montana were respectable and law-abiding; the usual rough-and-tumble population incident to the finding of gold was not conspicuous. As early as 1868, Helena established a public library to meet the demands of the reading public. Alder Gulch, also rich in precious metal, yielded $10,000,000 worth of gold from 1863 to 1869 and contained 14,000 people in 1864. Summit, Virginia City, and Nevada City mined $30,000,000 in the first three years of their existence.

But these camps, like Junction, Montana City, and Central City, which had come into existence in a day, soon worked themselves out, the population drifting to the larger camps; the population of Bannack in 1870 was 381; Virginia City, 867; Helena, 3,106; Gallatin, 152; Nevada City, 100; and Bozeman, 574.

The Idaho and Montana mines were easily reached from Fort Hall via the Oregon and California Trails, connected with a newly established road running northeastward from the old fort. In 1862, gold was discovered in the Boise Basin of Idaho. The richness of this camp created a stampede from other camps. By the spring of that year, the trails and roads leading to Boise Basin were crowded with eager miners coming from the camps of California and Nevada, the agriculturalists from Oregon and Washington, and all sorts and conditions of emigrants from the country east of the Rocky Mountains.

In the year following the finding of the gold, at least 30,000 people arrived at the diggings in Idaho in their frenzied desire for the yellow metal. The gold excitement in Montana and Idaho concurrently made the living conditions in that northwestern part of our country one of intense activity, great richness, and lawlessness.

Supplies were poured into these camps from Walla Walla, Washington, during November 1863, and $20,000 worth of dry goods were shipped over the trails into the camp. Utah rushed over the Salt Lake and Virginia City road, a pack train loaded with provisions. Gallatin Valley, Montana, was a favored spot for home seekers with an agricultural inclination, from where quantities of grain and vegetables were grown, which were used to feed those who toiled, not in the soil, but in the sands. The Gallatin Valley was an extensive meadow in which, in 1867, wonderful crops of wheat, oats, barley, buckwheat, and vegetables were grown that were more than sufficient to supply the growers who sent provisions to places in Montana where crops were not grown.

Fort Hall, Idaho.

The changing, feverish population in the camps was first composed of earnest and respectable people who had come to work for their gainings; following these came those who did not toil nor spin but who lived illicitly off of the earnings of others; the gamblers, the road agent, the murderer. The time soon came when decency asserted itself. Another class arose that believed that some semblance of law and order should be established, and having the courage of their convictions, organized themselves into Vigilance Committees. The people who had moved from regions where there was an established government did not long tolerate the law of the gun and organizations of desperadoes and road agents. Public opinion gradually began to crystallize for law and order. These vicious bands were perfectly organized, raiding all camps and operating along the roads between the camps. In Montana, the symbol of this red-handed band was a peculiar knot tied in their neckties so that outlaws‘ identities might be easily established. Often, hundreds of thousands of dollars were taken at one haul from the miners and merchants by these “desperate, crack-shot bands of robbers and cut-throats.” To protect life and property, the vigilantes were forced to organize, arrest members of the outlaw band, and act as judge, jury, and executioner. The hanging of a few of these robbers would always check, at least temporarily, the lawlessness of the outlaw bands.

The people of Montana did not resort to a vigilance code until forced to take drastic measures to disorganize and drive from the country the band of rapidly increasing desperadoes, which had created a reign of terror that was spreading over the camps. It was hard enough to wash the sands of the stream, working under the hostile eyes of Indians, but to have the fruits of toil taken by bandits could not long be tolerated. No one individual dared to punish the guilty who openly and publicly boasted of their crimes. High-handedness continued until regularly established courts were created and laws made by the legislature, but a wholesome fear of the vigilantes made living conditions more peaceful and bearable.

Into Montana had come many deserters from the South and many who were not in sympathy with the cause for which the Civil War was being fought. Some measures were taken to test their loyalty to the Union, the first being made when the emigrants and miners arrived at Fort Bridger, where each member of a party that was going over the Salt Lake-Virginia City Road had to take the “iron-clad” oath of allegiance to the United States. Anyone refusing to take the oath was not permitted to advance.

To facilitate transportation through the country situated between the Yellowstone and Columbia Rivers, Congress, early in 1857, made an appropriation for a proposed wagon road which was to run from Fort Benton, the western end of navigation up the Missouri River, to The Dalles, the head of navigation on the Columbia. It was believed that the mining camps would be helped in the district covered by the proposed roads if supplies coming from Missouri and California, as well as from Oregon to Montana, could be more easily and quickly transported over a constructed road than one that was not much more than a trail.

The construction of this military wagon road from Fort Walla Walla to Fort Benton was supervised by Lieutenant John Mullen, hence the name, who did his preliminary work in 1858; the hostilities of the Indians prevented the early completion of the road. The first work on the road was from Fort Benton to the Snake River; in 1860, the road was put into operation, though it was not entirely completed until 1862. This established a connecting line for transporting supplies to forts, camps, and homes from the Missouri River to the Columbia River, which might be called a rival transcontinental road of the Oregon Trail. The road operation relieved the freight congestion on that central trail to a degree. Three reasons existed for the Mullen Road: it shortened the distance to be traveled by wagons, lessened the hardships of the emigrants, and avoided the Indian raids along the Sweetwater and North Platte Route. There was a large migration in 1862. Some stopped on the eastern flank of the rocky range in Montana. Four steamers from St. Louis ascended to Fort Benton, and then 350 emigrants traveled by the Mullen Road to the mines of the Salmon River.

For miles, the Mullen Road followed the old trail made by the Indians on their annual hunts for buffalo from the Pacific to the east of the mountains. Some places on the old trail were twelve inches deep, made so by centuries of travel back and forth to and from these annual hunts.

Bozeman City, just west of Bozeman Pass, was established in 1864. Fort Ellis was built in 1867 to guard the Pass, which was within 16 miles of the ground of thousands of hostile Indians to the east. Before the fort was used in April 1867, the governor of Montana, when Indians infested Fort C.F. Smith, called for 600 mounted volunteers for service for 90 days to go to the pass and hold back the red men. Many members of this militia or Mounted Volunteers, when started on an offensive campaign, had a pan and other implements of the best quality for digging gold while clearing the road of Indians. These men were finally equipped to fight by the government until the regular soldiers took their place. In 1867, a messenger brought word to the soldiers guarding the pass of the desperate condition of the garrison at Fort C.F. Smith. The alarming information started John Bozeman and his companion over the trail to the besieged fort, on the way to which Blackfeet Indians killed Bozeman.

By 1865, Montana had a population of 120,000, which had to be fed and furnished with supplies not produced within that territory. Gold seekers had come over the mountains from the Pacific into the goldfields of Montana, a population producing nothing but gold and dependent on the outside for things to eat, clothing to wear, and supplies for their mining outfits. Products could be brought through the South Pass and Fort Hall, but the continental divide must be crossed twice before reaching Montana. Boating on the Missouri River to the head of navigation at Fort Benton was another way of transportation. However, after leaving the river to the camps, this road was through 300 miles of Indian territory and about 500 miles longer than a proposed road east of the Big Horn Mountains.

The mines of Idaho and Montana were the point of greatest traffic, and to make them more accessible, steps were taken in 1865 to establish a new road running north from the North Platte River west of old Fort Laramie. This road, which has been called the Montana Road, the Jacobs-Bozeman Cut-off, the Bozeman Road, the Powder River Road to Montana, the Big Horn Road, the Virginia City Road, the Bonanza Trail, the Yellowstone Road, the Reno Road, the Carrington Road, ultimately became known as the Bozeman Trail.

In the fall of 1860 and the spring of 1861, the Stuart brothers, James and Granville, found gold while prospecting in the Rocky Mountains of Montana. Writing to their brother Thomas, who was then mining in Colorado, they told glowing tales of the rich finds in that land to the northwest, urging him to come to the new goldfields. Thomas showed this letter to other young men there with him digging for gold.

A party of 12 young men was easily induced to leave Colorado in the spring of 1862, arriving in Montana in June. Among these young men was the sturdy and adventurous John M. Bozeman, for whom the Bozeman Trail, the city of that name, and the Bozeman Pass, between the Gallatin and Yellowstone Rivers, were named.

The desire for adventure and seeing the West brought Bozeman from his home in Coweta County, Georgia, where he had left his wife and two children. After settling in Montana, Bozeman became interested in finding and locating a possible cross-country road to the States. This road would materially shorten the distance that had to be traveled by old trails to reach the mining camps in Montana, particularly Bannack and Virginia City.

Bozeman and John M. Jacobs, in the winter of 1862-1863, left Bannack, then one of the most promising of young mining camps, for the Missouri River with a determination to find this shorter route for the emigrants and freighters on their way to the Montana goldfields. The customary longer routes then used were the water route up the Missouri River, the established trails, the Oregon and Overland, to Fort Hall, and the Fort Hall-Virginia City route.

Skirting along the south side of the Yelone River in search of a possible road to the North Platte River, the Sioux followed the two young men, who finally overtook Bozeman and his companion on the Powder River. The Indians stole their horses, ammunition, and guns and set the men afoot, doubtless believing that no white man could long survive in the dangerous red man’s country without a gun, horse, or food.

Bozeman and his companion experienced all the hardships possible. Wandering for days, starving, shoeless, and footsore, existing on a diet of grasshoppers, the exhausted but undaunted couple finally reached the Missouri River. In the spring of 1863, at the Missouri River, Bozeman took command of a wagon train of freighters and emigrants, determined to retrace his route on the east side of the Big Horn Mountains. When about 100 miles into this unknown country northwest of Fort Laramie, the Indians contested the right of the white men to use this part of their hunting grounds for a wagon road and drove the train back to the Sweetwater, from where the men sought the western slopes of the Big Horn Mountains, ultimately making safe passage into Montana. Bozeman did not accompany the train but made another attempt to go over his road.

From the North Platte River, Bozeman and nine of his men decided to defy fate by pushing north into a country filled with hostile Indians, a roadless distance of 700 miles. Making the journey by night to escape the vigilant eyes of the red men and enduring untold hardships, Bozeman finally reached the top of the Belt Mountains between the Gallatin and the Yellowstone Rivers. At this time, George W. Irvin, a member of Bozeman’s train, gave the pass the name of Bozeman.

From the journal of Captain James Stuart for May 11, 1863, an additional page of the life of Bozeman is to be found.

“Looking across the river, about a mile above us, I saw three white men with six horses, three packed, three riding. They were corning down the river, and I waited until they got opposite us. Then, I hailed them. They would neither answer nor stop but kept the same course at a faster pace. I then sent Underwood and Stone ahead of our pack train to overtake them and hear the news… We started to meet the strangers, not doubting, but our men had overtaken them… We met our men returning without having seen anything of the travelers… We followed them for ten miles and then gave up the chase. It seems that as soon as they got out of our sight, they had started on a run and kept in ravines and brush along the creek for about three miles till they got into the hills… We found that we could not overtake them. We found a frying pan and a pack of cards on their trail. None of us know who they are, where they come from, or where they were going.”

It was afterward learned that this party of three lone travelers consisted of John Bozeman and his partner, with his little eight-year-old daughter, being on their way from the Three Forks of the Missouri River to Red Buttes on the North Platte River. They were looking, it was ascertained, for a new wagon road which they found and which was afterward known as the “Jacobs and Bozeman Cut-off,” the name used at times for the Bozeman Trail. A few days before the adventure with Stuart and his men, Bozeman had had a brush with the Indians, and seeing Stuart’s men made Bozeman believe that there was to be an encounter with another band of Indians, and he did his utmost to make a safe escape.

Big Horn Mountains, Wyoming.

In 1864, Bozeman brought back a large train from the Missouri River, his line of travel between the Black Hills and the Big Horn Mountains, his cherished road. Jim Bridger was also taking a train in a new way he had found possible on the west side of the Big Horn Mountains and down Clark’s Fork. Bridger declared that Bozeman’s proposed road east of the mountains was impracticable. With several weeks ‘ start over the rival road on the west side of the Big Horn Mountains, Bridger finally reached the Yellowstone River ahead of Bozeman.” But his road took him into the Gallatin Valley, up the Shields River and Brackett Creek, and down Bridger Creek, a very roundabout route. Bozeman’s more direct route landed him in the Gallatin Valley ahead of Bridger. From this point, the two trains raced from West Gallatin into Virginia City, arriving but a few hours apart.

Again, in 1864, trail maker Bozeman successfully conducted another emigrant train over his chosen route to the Yellowstone River into the Gallatin Valley. The ease of travel, the shortening of miles, the abundance of water, timber, grass, and game, and the saving of time by using this road at once made this the most desired trail to Montana, mainly to the exclusion of the more frequent lines of travel. This way to the mines was known as “the Virginia City Road” and “the Bighorn Road.” Still, the original title for the man who dared to defy the Indians became the accepted appellation, the Bozeman Trail.

During July 1864, one emigrant train consisting of 150 wagons, 369 men, 36 women, 56 children, 667 oxen, 194 cows, 79 horses, and a dozen mules, with a valuation of $130,000, reached the goldfields over this forbidden path. Invasion of even one caravan of this magnitude enraged the Indians to hostile activity, for the penetration of this, their land, meant the destruction of the wild game and the influx and control by the whites. If fight it must be, the country of the Powder River and its minor streams was an inviting battlefield.

In April 1867, Bozeman and Tom Coover, on their way down the Yellowstone River en route to Fort C.F. Smith, made a camp where they encountered Indians, who stole many of their horses. On April 20, after this attack, while cooking the noon meal, five Indians entered the camp, leading the stolen horses of the day before. Bozeman, believing the Indians to be friendly Crow, invited them to the meal, when without warning, two Indians shot Bozeman through the body. Coover escaped into the bushes. The Indians stole the horses and blankets but did not scalp Bozeman. It was afterward learned that these Indians were the Blackfeet, fugitives from their tribe on account of having killed one of their chiefs and that, at this time, they were living with the Crow.

Two days after the killing of Bozeman, his partner, Coover, wrote for the public the following account of the murder:

General T. F. Meagher, Virginia City

“Sir: On the 16th, accompanied by the late J. M. Bozeman, I started for Forts C.F. Smith and Phil Kearny. After a day or so of arduous travel, we reached the Yellowstone River and journeyed on it in safety until the 20th inst., when in our noon camp on the Yellowstone, about seven miles this side of Bozeman Ferry, we perceived five Indians approaching us on foot and leading a pony. When within 250 yards, I suggested to Mr. Bozeman that we should open fire, to which he made no reply. We stood with our rifles ready until the enemy approached within 100 yards, at which Bozeman remarked: “Those are Crow; I know one of them. We will let them come to us and learn where the Sioux and Blackfeet camps are, provided they know.” The Indians meanwhile walked toward us with their hands up, calling, “Ap-sar-ake” (Crow).

They shook hands with Mr. B. and proffered the same politeness to me, which I declined by presenting my Henry rifle at them, and at the same moment, B. remarked, “I am fooled; they are Blackfeet. We may, however, get off without trouble.” I then went to our horses (leaving my gun with B.) and had saddled mine when I saw the chief quickly draw the cover from his fusee, and as I called to B. to shoot, the Indians fired, the ball taking effect in B’s right breast, passing completely through him. B. charged on the Indians but did not fire when another shot took effect in the left breast and brought poor B. to the ground, a dead man. At that instant, I received a bullet through the upper edge of my left shoulder. I ran to B. I picked up my gun and spoke to him, asking if he was severely hurt. Poor fellow! his last words had been spoken some minutes before I reached the spot: he was ‘stone dead.’ Finding the Indians pressing me and my gun not working, I stepped back slowly, trying to fix it, which I succeeded after retreating, say, 50 yards. I then opened fire, and the first shot brought one of the gentlemen to the sod. I then charged,d and the other two took to their heels, joining the two saddling B’s animal and our packhorse immediately after B’s fall. Having an idea that when collected, they might make a rush, I returned to a piece of willow brush, say 400 yards from the scene of action, giving the Indians a shot or two as I fell back. I remained in the willows for about an hour when I saw the enemy across the river, carrying their dead comrade with them. On returning to the camp to examine B, I found but too surely that the poor fellow was out of all earthly trouble. The red men, however, had been in too much of a hurry to scalp him or even take his watch — the latter I brought in. After cutting a pound or so of meat, I started on foot on the backtrack, swam the Yellowstone, walked 30 miles, and came upon McKenzie and Reshaw’s camp, very well satisfied to be so far on the road home and intolerable safe quarters. The next day I arrived home with a tolerable sore shoulder and pretty well fagged out. A party started out yesterday to bring in B’s remains. From what I can glean in the way of information, I am satisfied that there is a large party of Blackfeet on the Yellowstone River, whose sole object is plunder and scalps.

Yours etc. (Signed) T. W. Coover

Gallatine Mills, Bozeman, April 22, 1867

The Indian side of the killing of Bozeman is given in the following dictation (dictated by George Reed Davis, Crow interpreter, otherwise “Crow” Davis, of Laurel):

“In the year 1867, about the last of May or June 1, I was at Fort Laramie in the service of the government, and here, the tribe of the Crow were gathered to sign a treaty with the government at that time. At this time, a war party of young bucks (Crow) set out from the vicinity of Fort C.F. Smith to steal horses from the settlers in the Gallatin Valley. With this party of Crow were five (four) Piegan Indians, renegades from their tribe at that time, among them being Mountain Chief and three sons, one of whom was named Bull. Being successful in their raid for horses, the band started, on their return, with about 200 head of horses and had reached a point six miles below Mission Creek and about 16 miles east from the present of Livingston when they met two white men traveling up the river. I learned one of these was J. M. Bozeman and his companion, T. W. Coover, one of the discoverers of gold in Alder Gulch.

Not wishing to harm the whites or to be harmed by them, the Crow passed on, but the Piegan shortly disappeared from among them, which fact was not discovered for some time. The latter did not appear for some time, so the Crow started to hunt them up and found that they had killed Bozeman while away. The Piegans returned to camp with the Crow but, in November, returned to the Piegan tribe in northern Montana. Afterward, during the following years, the three sons of Mountain Chief and two other Piegans set out as a war party to steal horses from their former friends, the Crow. [They] were discovered by a band of Crow warriors under the leading warriors of the Crow tribe, Pretty Eagle and Ball Rock, in the Judith Gap in Judith Basin. [They] intercepted them and killed five of them. The Crow recognized them as the sons of Mountain Chief who had just left their camp and who killed Bozeman.”

April 1, 1896 (Signed) George Reed (“Crow”) Davis

Nelson Story, a pioneer of Bozeman, has caused a monument to be erected in the Bozeman cemetery over the grave of John M. Bozeman, a grave that stands at the brow of the bluff which the cemetery crowns and overlooks the beautiful city that has grown up since Bozeman ushered in its first settlers, presents new materials as to Bozeman’s death, which information was given to him by W. S. McKenzie.

The two (referring to Bozeman and Coover) had just finished dinner when the five Indians who had stolen our horses came up… They asked for food, and Bozeman good-naturedly consented to cook something for them. The only weapon the Indians had with them was an old gun, which we call a Mississippi yager. Bozeman had a Spencer gun, which he laid aside while cooking, and Coover, who stood nearby, had a first-class Henry gun. I had advised Bozeman not to let any Indian get close to him. The thing to have done when those Indians appeared with their demand for something to eat was to have killed them, for their presence meant no good, but Bozeman was a reckless man and never could see danger anywhere. While Bozeman cooked, he talked to one of the Indians. Suddenly, an Indian from behind the shelter of the one to whom Bozeman was talking fired at Bozeman. The ball struck him in the abdomen, killing him instantly… They found Bozeman’s body and buried it where it lay but could not get the Indians. Three or four days later, the body was disinterred and brought to Bozeman, and buried in the cemetery… Mountain Chief, one of the renegade Blackfeet, I saw at Fort C.F. Smith the year after. I tried to get the commanding officer to put him under arrest, but the officer feared the Indian would be hanged and trouble would ensue, so he would not accede to my request.”

The monument on the overlooking hill bears the following inscription:

“In memory of John M. Bozeman, aged 32 years, killed by Blackfeet Indians on the Yellowstone River, April 18, 1867. He was a native of Georgia and was one of the first settlers of Bozeman, from whom the town takes its name.”

A newspaper correspondent writing from Union City, Montana Territory, on October 21, 1867, a few months after Bozeman’s murder, makes this comment:

“The three murderers of Colonel Bozeman came in and received their annuities recently at Fort Benton and bore their gifts straightway to the hostile camps. Two of them were sons of a chief who professed to be at peace with the whites. He does the part of diplomacy while his sons and followers rob and butcher. A large portion of the annuities received by this tribe go to those who are on the warpath; he shields the fraud and aids the merciless enemy.”

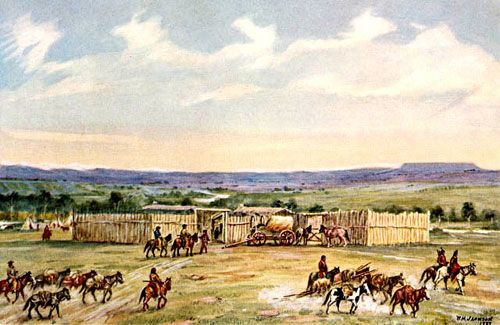

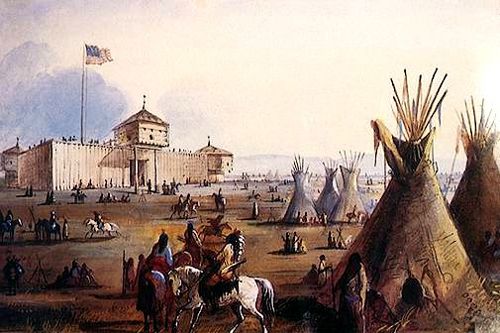

Fort Laramie, Wyoming, painting by Alfred Jacob Miller.

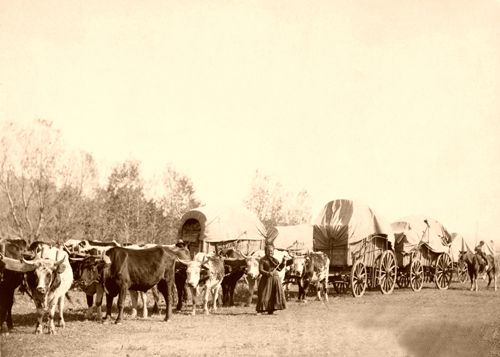

David B. Weaver crossed the plains on the Oregon Trail to Fort Laramie and Montana via the Bozeman Trail in the summer of 1864, leaving the Missouri River at Omaha on May 21 and arriving at Emigrant Gulch, Montana, on August 27. The data preserved from this journey and the incidents occurring on the way are interesting and inform us of daily travel and the dangers avoided and encountered. The trip by wagon train from the starting point to Fort Kearny, Nebraska, took until June.

Traveling along the north side of the North Platte, commonly called the Mormon Trail, Fort Laramie was a resting place on June 25. Then, the Indians’ path north of the fort was full of red men, so the small train of 20 wagons was advised not to proceed until recruit wagons might be added to the train.

Crossing the Platte River on a toll bridge kept by a Frenchman named Richard (pronounced “Reshaw”) to the south side, the few wagons waited until July 12, when reinforcements were added to the train until it numbered 68 wagons. A few days before the departure of this newly organized train, Captain Townsend had gone north on the Bozeman Trail with a wagon train, meeting, as was soon learned, serious disaster from Indian depredations.

Cyrus C. Coffenbury, having many wagons at the crossing, added Weaver’s wagon train to his own. He made up a train for Montana, was elected train commander, and had the title of Major. The train was divided into four divisions, with a captain for each section. Leaving the Platte River on July 12, no difficulties were experienced until the train reached the Powder River on July 22. Here, the men learned of the tragedy that had met Captain Townsend. Ten days before the train’s arrival, Townsend had been attacked by the Sioux, having four of his men killed, the naked and mutilated bodies of the soldiers bearing witness to the ravages of the Indians. Four empty graves near the bodies gave testimony to the savagery of the foe, who had not only dug up the bodies but had robbed them of clothing and the blankets in which they had been wrapped for burial.

Reburying the bodies, the train marched on, reaching Tongue River on July 29, being at that time 172 miles from the North Platte River. By August 4, the train was 62 miles beyond the Tongue River, where a camp was made on the Big Horn River. Here was found the “object of our quest,” color in the sand and gravel. Stretching toward the Yellowstone River, which was finally reached on August 14, the train followed the stream for nine days before they found a fordable place.

The trail ultimately took them west to a canyon 150 miles from where the train first obtained sight of the Yellowstone River. In the valley, many men were prospecting for gold, which attracted some of the men from the train who decided to go no further but try their luck washing for gold.

The party separated at this point on the Bozeman Trail, as the train members had different and varied destinations. Some expressed a wish to continue on the trail to Virginia City; others were allured to prospect along the valley of the Yellowstone River.

On August 8, Emigrant Gulch was reached by Mr. Weaver with a few of his men who wished to try their fortunes in the Yellowstone Valley. In this gulch, excited gold washers were feverishly working over the gravel. Thus, the “quest” is found in theiss surrounding the Bozeman Trail; the train disbanded, leaving each man to seek his fortune and destination as luck and wisdom might dictate.

A recital of the experiences of this train, protected by its members and organization, justified the government in its contention that the real dangers on the Bozeman Trail from the red men were inadequate mobilization of the trains and incompetent commanders or leaders of the trains.

In the summer of 1866, Hugh Kirkendall and others were on the Bozeman Trail on their way with a long train of household goods and merchandise for Montana. When the train reached Brown’s Springs, a branch of the Dry Fork of the Cheyenne, Indians attacked the train, and a running fight was kept up the entire day. As the hours of fighting increased, the Indians grew in numbers until it seemed as if all the Indians in the Powder River country had assembled for a final blow.

Being able finally to push the train forward, after the Indians were repulsed with heavy loss, the merchants came to within forty miles of Fort Phil Kearny, from where a scout was sent to the fort for soldiers to protect the train and conduct it beyond the fort. Word came in the morning that there were not enough soldiers to protect the fort with a small degree of safety. The wonder to the train members was that the three forts on the “Powder River Road” should have been built if enough soldiers had not been in them to protect not only the fortifications but also to assist and protect emigrant trains. “The fact is, the soldiers in the forts are practically bottled up, with the Indians galloping around on the hills nearby and defying them insultingly like Goliath of old.

The difficulties of one wagon train over the Bozeman Trail in the summer of 1866, when the Sioux were so intensively irritated, are but the repetition of many caravans to the Montana gold fields.

The trail followed the Union Pacific construction up the Platte. It was monotonously dull, plodding along beside the train. There were no variations in the monotony when the train left the railway line and swung up to Fort Laramie. But at Fort Laramie, the pilgrims left the beaten path. They were planning to take the Bozeman Trail from there into Montana, and the country’s condition ahead of them made it necessary that they travel with a big outfit.

At Fort Laramie, other freighting outfits were waiting for reinforcements, and the government authorities again warned small groups of emigrants of the immediate and certain danger from the Indians unless strongly guarded and moving in large numbers.

At the fort, this small group of freighters found a stockman with 3,000 heads of cattle from Texas to be taken into the Gallatin Valley for feeding and a wagon train of groceries to be sold in the mining camps of Montana. The forces all united, starting for the Powder River country, the Big Horn, Bozeman, and Virginia City. Had this combination of trains been consistently used, the depredations on the trail would have decreased, and human lives, cattle, supplies, ammunition, and guns would have been saved. Along the trail, the government was erecting a chain of military posts. General Carrington, who afterward negotiated the removal of Chariot on the Bitter Root, was in command of the troops engaged in the construction. One post, Fort Reno, had been completed. The building of Fort Kearny was in process. The posts further north had been located but not built. Some of them never were built.

The train moved on without serious incident. The country was alive with Indians. There were signs of fighting-burned wagons and dead stock in places, and at times, the Story outfit would spy Indians at a distance. But it was not until within about ten miles of Fort Reno that there was any open hostility toward the train. That was probably due to Story’s keen outlook and intimate knowledge of the country.

There were thousands of Indians within striking distance of the train, but the train was not molested until it reached a point so close to the new post as to seem safe. On the edge of the badlands, the train was attacked. There was a brisk engagement, but it didn’t last long; probably, the Indians who had been spying on the train were merely trying it out, or perhaps they could not resist stealing the stock cattle being driven with the train. However, as it was, the reds swooped down on the travelers with a flight of arrows, but nobody was killed. The cattle were finally recaptured, and messengers were to Fort Reno for an ambulance.

An hour before, the train had its brush with the Indians; it met a Frenchman and his boy with a trapper’s outfit, the two making camp for the night. Though the large train invited the Frenchman to unite with the larger band, the old man refused the offer, saying his fear for the white men was greater than that of the Indians. The next day proved the fallacy of the lone emigrant and hunter, for the scalps of both, were taken; their bodies, badly mutilated, their wagons were burned, food scattered over the prairie, and their horses stolen.

Leaving Fort Reno, the train pushed north and west toward Fort Phil Kearny, where General Carrington was surveying and actively assisting in the construction of the main fortification that was to be built on the Bozeman Trail. The soldiers from the fort came down three miles to meet the train, forbidding further advance to the fort, as the meadows around the fort site were reserved for government stock. Further instructions were given not to attempt to go further north, as there were danger signals about Indians north of the fort.

“We were camped about three miles from the post, so far that the soldiers could not have rendered us any assistance if we were attacked; we were forbidden to proceed, as the soldiers couldn’t leave their building operations to escort us; we just had to sit still and twirl our thumbs. While waiting, the freighters built two corrals, one for the work cattle and one for the Texas and stock. One night, after two weeks of impatient waiting for permission to advance, the entire train, oxen, wagons, cattle, and men disappeared, moving on beyond the fort in the silence and darkness of night. The Indians were more afraid of the twenty-seven men of the train than the 300 soldiers at the partially built fort on the Piney. The troops had the old-style Springfield rifles, while the freighters had Remington breech loaders, a style of gun not introduced on the plains for the forts until the following year. Twenty-seven Remingtons were enough to stand off 3,000 red men with bows and arrows after we got them scared.”

The success of traveling by night convinced the train that this was a safer method of travel than going by day; hence, they rested during the day and traveled after sundown. The train was attacked three times during the day, and the Indians were easily stood off, the men being on their guard. As the train moved further north, the Indians became less numerous, an estimation placing the number of red men around Fort Phil Kearny on October 22, when the train was near the fort, as 3,000. The Fetterman fight occurred two months from this date, the initial big fight with Indians in the Powder River country.

These night marches finally brought the train to Fort C.F. Smith’s site, where the Crow had their villages. From this point, the party journeyed to the northwest and forded Yellowstone at the place where another Bozeman Trail fort called Fort Fisher was to be built. Due to a lack of adequate soldiers, General Carrington could not construct the needed and promised fortification. Down Emigrant Gulch, the train slowly made its way to Bozeman, with no Indian troubles being encountered. At last, the end of the trail was reached in Virginia City.”

Oxen did the principal freighting to the Bozeman Trail forts because the red men did not care for cattle, and the country through which the trail passed was full of wild game of many kinds. What the Indians coveted were the white man’s horses and mules for which he was willing to make tremendous sacrifices. There were no regular stage lines on the Bozeman Trail; the military forces carried all of the mail from the Platte to Fort C. F. Smith. The river route received mail for Fort Ellis, Bozeman, and beyond to Virginia City from Fort Benton or the Virginia City Stage Road from Salt Lake City.

During those months when the Missouri River was open to navigation, there was no heavy freighting over the Bozeman Trail west of Fort C.F. Smith. The supplies were shipped to Fort Benton or Benson’s Landing at the head of navigation on the Yellowstone, about 30 miles southeast of Fort Ellis, and from these two points, they were redistributed to the various camps and cities in Montana.

In the fall of 1866 at Bozeman, Nelson Story took his oxen and wagon team filled with flour and vegetables to Fort C.F. Smith, where he sold the supplies to the government for the soldiers at the fort. From that date until the old trail was abandoned in 1868, Story continued to regularly supply this fort with food, though not any traffic was carried on the east of the fort, where the hostilities were constant from the Sioux. The hostile Indians, the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, were seldom troublesome West of Pryor’s Creek. The hostilities in that part of the country, crossed by the Bozeman Trail, were carried on by the Blackfeet Indians.

If the Santa Fe Trail was a road of commerce, the Oregon Trail was the home seeker’s path, the Overland Trail was the route of the mail and express, and the Bozeman Trail was the battleground of the Fighting Sioux.

By Grace Raymond Hebard and Earl Alonzo Brininstool, 1922. Compiled Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

About the Authors: Grace Raymond Hebard and Earl Alonzo Brininstool were Western historians in the early 20th century. This account was excerpted from their book, The Bozeman Trail: Historical Accounts of the Blazing of the Overland Routes Into the Northwest, published by the Arthur H. Clark Company in 1922. The article on these pages is not verbatim, as it has been very briefly edited, primarily for spelling and grammatical corrections.

Also See:

The Bozeman Trail – A Violent Path to the Gold Fields

Santa Fe Trail – Highway to the Southwest

Oregon Trail – Pathway to the West

The Overland Stage and Telegraph Lines