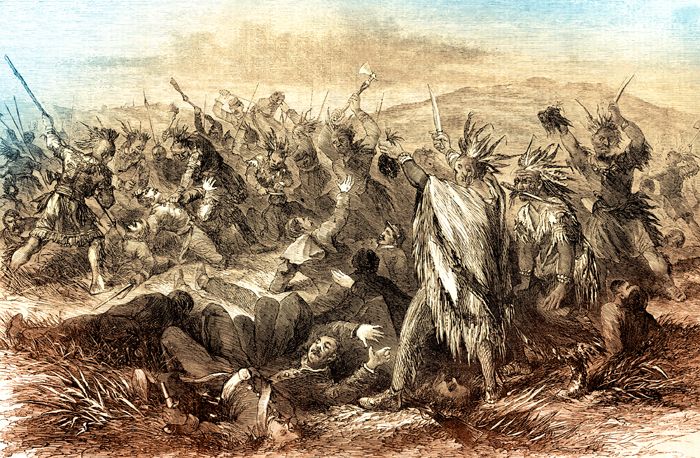

Attacking Sioux

The tragic events associated with Fort Phil Kearny, the Fetterman Massacre, and the Wagon Box Fight form one of the most dramatic chapters in the history of the Indian Wars. For two bloody years from 1866 to 1868, the Sioux Indians, bitter and opposing the invasion of their hunting grounds by prospectors bound over the Bozeman Trail to the Montana goldfields, fought back viciously. It was one of the few instances during the Indian Wars when the Army was forced to abandon a region it had occupied when the Sioux triumphed and the forts were evacuated. But the conflict foreshadowed the final disastrous confrontation between frontiersmen and Indians that ensued on the northern Plains as the westward movement accelerated after the Civil War.

Strikes in 1862 by Idaho prospectors in the mountains of western Montana triggered a rush to the diggings at Bannack and subsequently to Virginia City. The next spring John M. Bozeman and John M. Jacobs blazed the Bozeman Trail.

Running north from the Oregon-California Trail along the eastern flank of the Bighorn Mountains and then westward, it linked Forts Sedgwick, Colorado, and Laramie, Wyoming, and the Oregon-California Trail with Virginia City. Spared the circuitous route through Salt Lake City, gold seekers soon poured over the trail, which crossed the heart of the hunting grounds the hostile Sioux had recently seized from the Crow. The Sioux, taking advantage of the absence of Regular troops in the Civil War, quickly unleashed their fury.

In 1865, at Fort Sully, South Dakota, the government concluded treaties with a few Sioux chiefs. In return for the promise of annuities, they agreed to withdraw from the vicinity of emigrant routes and not to attack them. The commissioners, however, had dealt with only unimportant leaders of the bands along the Missouri River — not the people who really mattered. Red Cloud, Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses, and other chiefs who roamed the Powder and Bighorn country to the West vowed to let no travelers pass unmolested.

In the late spring and summer of 1866, a U.S. commission met with these leaders at Fort Laramie, Wyoming. In the midst of the council, Colonel Henry B. Carrington and 700 men of the 18th Infantry marched into the fort. When Red Cloud and the other chiefs learned that their mission was the construction of forts along the Bozeman Trail, they stalked out of the conference and declared war on all invaders of their country. That summer and fall Carrington strengthened and garrisoned Fort Reno and erected Forts Phil Kearny and Fort C.F. Smith.

Sioux, Arapaho, and Northern Cheyenne warriors had all but closed the trail. Between August 1st and December 31st, they killed 154 people in the vicinity of Fort Phil Kearny, wounded 20 more, regularly attacked emigrants, and destroyed or captured more than 750 head of livestock. Even heavily guarded supply trains had to fight their way over the trail. The forts endured continual harassment, and wagon trains hauling wood for fuel and construction had to ward off assaults.

Sioux efforts focused on Carrington’s headquarters, Fort Phil Kearny, situated between the Big and Little Piney Forks of the Powder River on a plateau rising 50 to 60 feet above the valley floor. The largest of the three posts guarding the Bozeman Trail, it was one of the best fortified western forts of the time. Construction began on July 13, 1866, and it ultimately consisted of 42 log and frame buildings within a 600 by 800-foot stockade of heavy pine timber 11 feet high and had blockhouses at diagonal corners. A company of the 2nd Cavalry reinforced Carrington’s infantry.

Strong defenses were necessary. The warnings of Red Cloud had not prevented the fort’s establishment, but he soon put it under virtual siege. Carrington, saddled with 21 women and children dependents who had accompanied him from Fort Kearny, Nebraska, maintained a defensive stance. A clique of his younger and more impetuous officers, who disliked him and resisted his attempts to impose discipline, were contemptuous. Prominent among them was Captain William J. Fetterman, who boasted that he and 80 men could ride through the whole Sioux Nation.

On December 21, 1866, a small war party, in a feint, made a typical attack on a wood train returning eastward from Piney Island to the fort. To relieve the train, Carrington sent out Fetterman, two other officers, 48 infantrymen, 28 cavalrymen, and two civilians—81 men in all. Although warned not to cross Lodge Trail Ridge, where he would be out of sight of the fort, Fetterman let a small party of warriors decoy him northward well beyond the ridge and into a carefully rehearsed ambush prepared by Red Cloud. Within half an hour, at high noon, hundreds of Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors annihilated the small force to the last man. Relief columns from the fort, which scattered the Indians, were too late to rescue Fetterman and his men. They had suffered the worst defeat inflicted by the Plains Indians on the Army until that time and one that vied with subsequent debacles, such as the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Following the Fetterman Massacre, Carrington hired civilians John “Portugee” Phillips and Daniel Dixon to carry a message for Omaha headquarters concerning the disaster and a plea for reinforcements to the telegraph station at Horseshoe Bend, near Fort Laramie. Phillips continued on through a snowstorm to Fort Laramie on a 236-mile ride, honored in the annals of Wyoming history. Carrington was replaced in January 1867.

By that summer the Indians had closed the Bozeman Trail to all but heavily guarded military convoys, but the troops won two victories. The Sioux and Cheyenne agreed to pool their resources and wipe out Forts Phil Kearny and C.F. Smith in Montana. One faction, in the Hayfield Fight, attacked a haying party near Fort C.F. Smith on August 1st but suffered heavy casualties. The next day the other group, 1,500 to 2,500 Sioux and Cheyenne led by Red Cloud, set upon a detachment of 28 infantrymen guarding civilian woodcutters a few miles west of Fort Phil Kearny. Most of the civilians succeeded in safely reaching the post, but four were trapped with the soldiers in an oval barricade that had been formed earlier as a defensive fortification from the overturned boxes of 14 wood-hauling wagons that had been removed from the running gears. The troops were armed with newly issued breech-loading Springfield rifles—a costly surprise for the Sioux. Six times in four hours they charged the wagon boxes, but each time was thrown back with severe casualties. Reinforcements finally arrived from the fort with a mountain howitzer and quickly dispersed the opposition. The Army reported only about three dead and two wounded, but the Indians claimed the figures were at least 60 and 120, respectively.

Indian tipis on the grounds of Fort Phil Kearny, in what is now Johnson County, Wyoming. Photo by Carol Highsmith.

The Hayfield and Wagon Box Fights exacted a modicum of revenge for the Fetterman Massacre, but they did not deter hostilities. Forays increased steadily until the next year when the government was forced to come to terms with the Indians. In the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868), in return for certain Indian concessions, it bowed to Red Cloud’s demands and agreed to close the Bozeman Trail and abandon the three forts protecting it. As soon as this occurred, in July and August, the Sioux, unknowingly celebrating the zenith of their power on the northern Plains, jubilantly burned them to the ground.

The basically unaltered natural scene of the sites of Fort Phil Kearny, the Fetterman Massacre, and the Wagon Box Fight, despite surrounding ranch operations, are marred by but few modern intrusions. Nothing remains of the fort, which was located is about one mile west of U.S. 87 and 2½ miles southeast of Story. The site is marked by one side of a stockade, all that survives from a Works Progress Administration (WPA) reconstruction in the 1930s, and a log cabin erected by the Boy Scouts. The State owns three acres of the probable 25-acre site. About five miles to its north, along U.S. 87 and about 1½ miles northeast of Story, Wyoming is the spur ridge east of Peno Creek, and the route of the Bozeman Trail, along which Fetterman and his men retreated southward. At the southern end of the estimated 60 privately owned acres embracing the battlefield, at the point where most of the bodies were found, stands a War Department monument on a tiny tract of Federal land on the east side of the highway. The only modern intrusion of consequence is the highway. Another monument, lying in an upland prairie some 1½ miles southwest of Story, marks the location of the Wagon Box Fight, one acre of which is State-owned out of an estimated 40-acre total.

Today the state historic site provides an interpretive center with exhibits, videos, bookstore, and self-guided tours of the fort and outlying sites. The fort tour leads the visitor through the site to building locations, archaeological remains, and interpretive signs pinpointing the surrounding historic landmarks. A Civilian Conservation Corp Cabin has been refurbished to depict the quarters of an Officer’s wife and a Non-Commissioned Officer’s Quarters. At both battlefield sites, visitors will find an interpretive trail that leads through the battle providing both Indian and White perspectives of the conflict.

The fort site and those of the Fetterman Massacre and Wagon Box Fight lie within a few miles of one another just off I-90 in the vicinity of Story, Wyoming. The fort and Wagon Box sites are located on secondary roads, and the Fetterman Massacre site is on U.S. 87. Follow road markers.

Contact Information:

Fort Phil Kearny State Historic Site

528 Wagon Box Road

Banner, Wyoming 82832

307-684-7629

Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated July 2022.

Also See:

Adventures on the Bozeman Trail

Red Cloud – Lakota Warrior and Statesman

Fort Laramie – Crossroads to the West

Primary Source: National Park Service