By Emerson Hough in 1905

Outlawry of the early border, in days before any pretense at the establishment of a system of law and government and before the holding of the property had assumed any very stable form, may have retained a certain glamour of romance. The loose gold of the mountains, the loose cattle of the plains, before society had fallen into any strict way of living, and while plenty seemed to exist for any and all, made a temptation easily accepted and easily excused. The ruffians of those early days had a largeness in their methods, giving some of them at least a color of interest. Suppose any excuse may be offered for lawlessness, any palliation for acts committed without the countenance of the law. In that case, that excuse and palliation may be pleaded for these men, if for any. But little can be said for the man who is bad and mean as well, who kills for gain, and who adds cruelty and cunning to his acts instead of boldness and courage. Such characters afford us horror, but it is horror unmingled with any manner of admiration.

Yet, if we reconcile ourselves to tarry a moment with the cheap and gruesome, the brutal and ignorant side of mere crime, we shall be obliged to take into consideration some of the bloodiest characters ever known in our history; which operated well within the day of established law; who made a trade of robbery, and whose capital consisted of disregard for the life and property of others.

That men like this should live for years at the very door of large cities, in an old settled country, and known familiarly in their actual character to thousands of good citizens is a strange commentary on the American character, yet such are the facts.

It has been shown that a widely extended war always cheapens human life in and out of the ranks of the fighting armies. The early wars of England, in the days of the longbow and buckler, brought on her palmiest days of cutpurses and cutthroats. The days following our Civil War were fearful for the entire country from Montana to Texas, and nowhere more so than along the dividing line between North and South, where feeling far bitterer than soldierly antagonism marked a large population on both sides of that contest. We may further restrict the field by saying that nowhere on any border was animosity so fierce as in western Missouri and eastern Kansas, where jayhawker and border ruffian waged a guerrilla war for years before the nation was arrayed against itself in ordered ranks. If mere blood is a matter of our record here, assuredly, it is a field of interest. The deeds of James Lane and John Brown, of William Quantrill and Charles Hamilton, are not surpassed in terror in the history of any land. Osceola, Missouri; Marais du Cygne and Lawrence, Kansas — these names warrant a shudder even today.

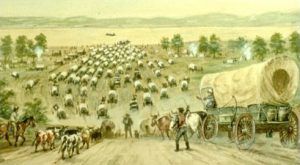

This locality — say that part of Kansas and Missouri near the towns of Independence and Westport, and more especially the counties of Jackson and Clay in the latter state — was always turbulent and had reason to be. Here was the halting place of the westbound civilization, at the edge of the plains and the line dividing the whites from the Indians. Like the gravel along the sluice’s cleats, the daring men who had pushed west from Kentucky, Tennessee, lower Ohio, and eastern Missouri were the Boones, Carsons, Crocketts, and Kentons of their day. Here came the Mormons to found their towns and later to meet the armed resistance that drove them across the plains. Here, at these very towns, was the outfitting place and departing point of the caravans of the early Santa Fe trade; here, the Oregon Trail left for the far Northwest, and here, the Forty-niners paused a moment in their mad rush to the golden coast of the Pacific. Here, too, adding the bitterness of fanaticism to the courage of the frontier, came the bold men of the North who insisted that Kansas should be free to expand the northern population and institutions.

This corner of Missouri-Kansas was a focus of recklessness and daring for more than a whole generation. The children born there had an inheritance of indifference to death, as has been surpassed nowhere in our frontier unless that were in the bloody Southwest. At the outbreak of the Civil War, the men of this country made as high an average in desperate fighting as any that ever lived. Too restless to fight under the ensign of any but their own ilk, they set up a banner of their own. The black flags of Quantrill and Lane, of border ruffian and jayhawker, were guidons under which quarter was unknown and mercy a forgotten thing.

Warfare became murder, and murder became assassination. Ambushing, surprise, pillage, and arson went with murder, and women and children were killed and fighting men. Is it a wonder that in such a school, there grew up those figures which a particular class of writers has been wont to call bandit kings: the bank robbers and train robbers of modern days, the James and Younger type of bad men.

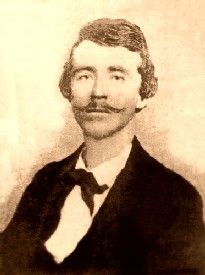

The most notorious of these border fighters was the bloody leader, William Quantrill, the leader at the Sacking of Lawrence. As dangerous a partisan leader as ever threw his leg into the saddle. He was born in Hagerstown, Maryland, on July 31, 1837, and as a boy, lived for a time in the Ohio city of Cleveland. At age 20, he joined his brother for a trip to California via the Great Plains. This was in 1856, and Kansas was full of Free Soilers, whose political principles were not always un-tempered by a large-minded willingness to rob. A party of these men surprised the Quantrill party on the Cottonwood River and killed the older brother. William Quantrill swore undying revenge, and he kept his oath.

It is not necessary to mention in detail the deeds of this border leader. They might have had commendation for their daring had it not been for their brutality and treachery. Quantrill had a band of sworn men held under solemn oath to stand by each other and to keep their secrets. These men were well armed and well mounted, were all fearless and all good shots, the revolver being their especial arm, as it was of Mosby’s men in the Civil War. The tactics of this force comprised surprise, ambush, and a determined rush, in turn; and time and again, they defeated Federal forces many times their number, being thoroughly well acquainted with the country and scrupling at nothing in the way of treachery, just as they considered little the odds against which they fought. Their victims were sometimes paroled, but not often, and a massacre usually followed a defeat.

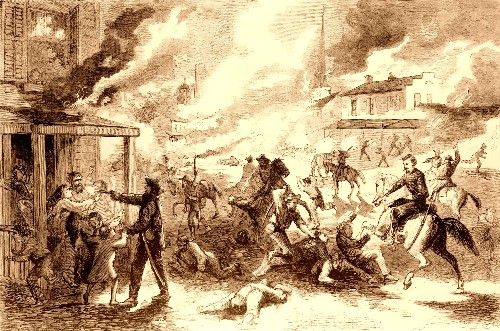

The cold-blooded and unhesitating murder was part of their everyday life. Thus Jesse James, on the march to the Lawrence Massacre, had in charge three men, one of them an old man, whom they took along as guides from the little town of Aubrey, Kansas. They used these men until they found themselves within a few miles of Lawrence, and then, as is alleged, members of the band took them aside and killed them, the old man begging for his life and pleading that he had never done them any wrong. His murderers were no more than boys. This act may have been that of bad men, but not of the sort of bad men that leaves us any sort of respect, such as that which may be given Wild Bill, even Billy the Kid, or any of a dozen other big-minded desperadoes.

This assassination was but one of scores or hundreds. A neighbor suspected of Federal sympathies was visited in the night and shot or hanged, his property destroyed, and his family killed. The climax of the Lawrence Massacre was simply the working out of principles of blood and revenge. In that fight, or, more properly, that massacre, women and children went down as well as men. The James boys were Quantrill riders, Jesse a new recruit, and that day, they maintained that they had killed sixty-five persons between them and wounded 20 more! What was the total record of these two men alone in all this period of guerrilla fighting? It cannot be told. Probably, they themselves could not remember. The four Younger boys had records almost or quite as bad.

There, indeed, was a border soaked in blood, a country torn with intestinal warfare. Quantrill was beaten now and then, meeting fighting men in blue or in jeans, as well as leading fighting men; and at times, he was forced to disband his men, later to recruit again, and to go on with his marauding up and down the border. His career attracted the attention of leaders on both sides of the opposing armies. At one time, it was nearly planned that Confederates should join the Unionists and make common cause against these guerrillas, who had made the name of Missouri one of reproach and contempt. The matter finally adjusted with Quantrill’s death in a fight at Smiley, Kentucky, in January 1865.

With birth and training such as this, what could be expected of the surviving Quantrill men? They scattered over all the frontier, from Texas to Minnesota, and most of them lived in terror of their lives after that, with the name of Quantrill as a term of loathing attached to them where their earlier record was known. Many and many border killings years later and far removed in the locality arose from the implacable hatred that descended from those days.

As for the James boys, the Younger boys, what could they do? The days of war were gone. There were no longer any armed banners arrayed one against the other. The soldiers who had fought bravely and openly on both sides had laid down their arms and fraternized. The Union grew strong and indissoluble. Men settled down to farming, to artisanship, to merchandising, and their wounds were healed. Amnesty was extended to those who wished it and deserved it. These men could have found a living easy to them, for the farming lands still lay rich and ready for them. But they did not want this life of toil. They preferred the ways of robbery and blood in which they had begun. They cherished animosity now, not against the Federals, but against mankind. The social world was their field of harvest, and they reaped it, weapon in hand.

The James family originally came from Kentucky, where Frank was born, in Scott County, in 1846. The father, Robert James, was a Baptist minister of the Gospel. He removed to Clay County, Missouri, in 1849, and Jesse was born there in 1850. Reverend Robert James left for California in 1851 and never returned. The mother, a woman of great strength of character, later married Doctor Samuels. The persecution of her family much embittered her, as she considered it. She herself lost an arm in an attack by detectives upon her home, in which a young son was killed. The family had many friends and confederates throughout the country; otherwise, the James boys must have found an end long before they were brought to justice.

From the same surroundings came the Younger boys, Thomas Coleman, or “Cole,” Younger, and his brothers, John, Bruce, James, and Robert. Their father was Henry W. Younger, who settled in Jackson County, Missouri, in 1825 and was known as a man of ability and worth. For eight years, he was a county judge and was twice elected to the state legislature. He had fourteen children, of whom five certainly were bad.

At one time, he owned large bodies of land and was a prosperous merchant in Harrisonville for some time. Cole Younger was born January 15, 1844, John in 1846, Bruce in 1848, James in 1850, and Bob in 1853. As these boys grew old enough, they joined the Quantrill bands, and their careers were precisely the same as those of the James boys. The cause of their choice of sides was the same. Charles Jennison, the Kansas Jayhawker leader, in one of his raids into Missouri, burned the houses of Youngers and confiscated the horses in his livery stables. After that, the boys of the family swore revenge.

At the close of the Civil War, the Younger and James boys worked together often and were leaders of a band that had a cave in Clay County and numberless farmhouses where they could expect shelter in need. With them, part of the time were George and Ollie Shepherd; other members of their band were Bud Singleton, Bob Moore, Clell Miller, and his brother, Arthur McCoy; others who came and went from time to time were regularly connected with the bigger operations. It would be wearisome to recount the long list of crimes these men committed for ten or fifteen years after the war. They certainly brought notoriety to their country. They had the entire press of America reproaching the State of Missouri; they had the governors of that state and two or three others at their wits’ end; they had the best forces of the large city detective agencies completely baffled. They killed two detectives — one of whom, however, killed John Younger before he died — and executed another in cold blood under circumstances of repellant brutality. They raided over Missouri, Kansas, Kentucky, Tennessee, even as far east as West Virginia, as far north as Minnesota, as far south as Texas, and even old Mexico. They looted dozens of banks and held up as many railway passenger trains and as many stagecoaches and travelers as they liked. The James boys alone are known to have taken in their robberies $275,000, and, including the unlawful gains of their colleagues, the Youngers, no doubt they could have accounted for over half a million dollars. They laughed at the law, defied the state and county governments, and rode as they liked, here, there, and everywhere until the name of law in the West was a mockery. If magnitude in crime claims to distinction, they might ask the title, for surely their exploits were unrivaled and perhaps cannot again be equaled. And they did all these unbelievable things in the heart of the Mississippi Valley, in a country thickly settled, in the face of a long reputation for criminal deeds, and in a country fully warned against them. Surely, it seems sometimes that American law is weak.

It was much the same story in the long list of robberies of small country banks. A gang member would locate the bank and get an idea of the interior arrangements. Two or three of the gang would step in and ask to have a bill changed; then, they would cover the cashier with revolvers and force him to open the safe. If he resisted, he was killed, sometimes killed, no matter what he did, as was cashier Sheets in the Gallatin bank robbery. The guard outside kept the citizens terrified until the booty was secured; then, a flight on good horses followed. After that ensued the frantic and unorganized pursuit by citizens and officers, possibly another killing or two en route, and a return to their lurking place in Clay County, Missouri, where they never had any difficulty in proving all the alibis they needed.

None of these men ever confessed to a full list of these robberies, and even years later, they all denied complicity. Still, the facts are too well known to warrant any attention to their denials, founded upon a very natural reticence.

Of course, their safety lay in the sympathy of a large number of neighbors of something the same kidney; and fear of retaliation supplied the only remaining motive needed to enforce secrecy.

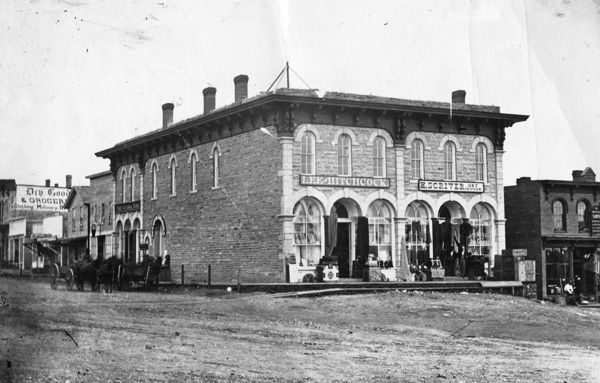

The first bank to be robbed by the James-Younger Gang was in Liberty, Missouri, on February 13, 1866. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

Some of the most noted bank robberies in which the above-mentioned men, or some of them, were known to have been engaged were as follows: The Clay County Savings Association, of Liberty, Missouri, February 14, 1866, in which a little boy by name of Wymore was shot to pieces because he obeyed the orders of the bank cashier and gave the alarm; the bank of Alexander Mitchell & Co., Lexington, Missouri, October 30, 1860; the McLain Bank, of Savannah, Missouri, March 2, 1867, in which Judge McLain was shot and nearly killed; the Hughes & Mason Bank, of Richmond, Missouri, May 23, 1867, and the later attack on the jail, in which Mayor Shaw, Sheriff J. B. Griffin, and his brave fifteen-year-old boy were all killed; the bank of Russellville, Kentucky, March 20, 1868, in which cashier Long was badly beaten; the Daviess County Savings Bank, of Gallatin, Missouri, December 7, 1869, in which cashier John Sheets was brutally killed; the bank of Obocock Brothers, Corydon, Iowa, June 3, 1871, in which forty thousand dollars was taken, although no one was killed; the Deposit Bank, of Columbia, Missouri, April 29, 1872, in which cashier R. A. C. Martin was killed; the Savings Association, of Ste. Genevieve, Missouri; the Bank of Huntington, West Virginia, September i, 1875, in which one of the bandits, McDaniels, was killed; the Bank of Northfield, Minnesota, September 7, 1876, in which cashier J. L. Haywood was killed, A. E. Bunker wounded, and several of the bandits killed and captured as later described.

These same men or some of them also robbed a stagecoach now and then, near Hot Springs, Arkansas, for example, on January 15, 1874, where they picked up $4,000 and included ex-Governor Burbank of Dakota among their victims, taking from him alone $1500; the San Antonio- Austin coach, in Texas, May 12, 1875, in which John Breckenridge, president of the First National Bank of San Antonio, was relieved of $1000; and the Mammoth Cave, Kentucky, stage, September 3, 1880, where they took nearly $2000 in cash and jewelry from passengers of distinction.

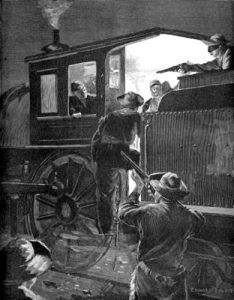

However, the most daring of their work, which brought them into contact with the United States government for tampering with the mail, was their repeated robbery of railway mail trains, which became a matter of simplicity and certainty in their hands. To flag a train or to stop it with an obstruction, or to get aboard and mingle with the train crew, then to halt the train, kill anyone who opposed them, and force the opening of the express agent’s safe, became a matter of routine with them in time. The amount of cash they thus obtained was staggering in the total.

The most noted train robberies in which members of the James-Younger bands were engaged were the Rock Island train robbery near Council Bluffs, Iowa, July 21, 1873, in which engineer Rafferty was killed in the wreck, and but small booty secured; the Gad’s Hill, Missouri, robbery of the Iron Mountain train, January 28, 1874, in which about $500 was secured from the express agent, mail bags, and passengers; the Kansas Pacific train robbery near Muncie, Kansas, December 12, 1874, in which they secured more than $55,000 in cash and gold dust, with much jewelry; the Missouri-Pacific train robbery at Rocky Cut, July 7, 1876, where they held the train for an hour and a quarter and secured about $15,000 in all; the robbery of the Chicago & Alton train near Glendale, Missouri, October 7, 1879, in which the James boys’ gang secured between $35,000 and $50,000 in currency; the robbery of the Rock Island train near Winston, Missouri, July 15, 1881, by the James boys’ gang, in which conductor Westfall was killed, messenger Murray badly beaten, and a passenger named MacMillan killed, little booty being obtained; the Blue Cut robbery of the Alton train, September 7, 1881, in which the James boys and eight others searched every passenger and took away a two-bushel sack full of cash, watches, and jewelry, beating the express messenger badly because they got so little from the safe. This last robbery caused the resolution of Governor Crittenden of Missouri to take the bandits dead or alive, a reward of $30,000 being arranged by different railways and express companies, a price of $10,000 each being put on the heads of Frank and Jesse James.

Outside of this long list of the bandit gang’s deeds of outlawry, they were continually in smaller undertakings of a similar nature. Once, they took away $10,000 in cash at the box office of the Kansas City Fair on September 26, 1872, in a crowded city with all the modern machinery of the law to guard its citizens. Many acts at widely separated parts of the country were accredited to the Younger or the James boys. Although they cannot have been guilty of all of them, and although many of the adventures accredited to them in Texas, Mexico, California, the Indian Nations, etc., bear earmarks of doubtful origin, there is no doubt that for twenty years after the close of the Civil War they made a living in this way, their gang being made up of perhaps a score of different men in all, and usually consisting of about six to ten men, according to the size of the undertaking on hand.

Meantime, all these years, the list of homicides for each of them was growing. Jesse James killed three men out of six who attacked his house one night, and not long after, Frank, and he were alleged to have killed six men in a gambling fight in California. John and Jim Younger killed the Pinkerton detectives Lull and Daniels, John being himself killed at that time by Daniels. A little later, Frank, Jesse James, and Clell Miller killed Detective Wicher of the same agency, torturing him for some time before his death to make him divulge the Pinkerton plans. The James boys killed Daniel Askew in revenge, and Jesse James and Jim Anderson killed Ike Flannery for the motives of robbery. This last set the gang into hostile camps, for Flannery, was a nephew of George Shepherd. Shepherd later killed Anderson in Texas for his share in that act; he also shot Jesse James and, for a long time, supposed he had killed him.

The full record of these outlaws will never be known. Their career ended soon after the heavy rewards were put upon their heads, and it came in the usual way, through treachery. Allured by the prospect of gaining ten thousand dollars, two cousins of Jesse James, Bob and Charlie Ford, pretending to join his gang for another robbery, became members of Jesse James’ household while he was living incognito as Thomas Howard. On the morning of April 3, 1882, Bob Ford, a mere boy not yet 20 years of age, stepped behind Jesse James as he was standing on a chair dusting off a picture frame and, firing at close range, shot him through the head and killed him. Bob Ford never got much respect for his act, and his money was soon gone. He was killed in February 1892 at Creede, Colorado, by a man named Kelly.

Jesse James was about five feet ten inches in height and weighed about one hundred and sixty-five pounds. His hair and eyes were brown. He had, during his life, been shot twice through the lungs, once through the leg, and had lost a finger of the left hand from a bullet wound.

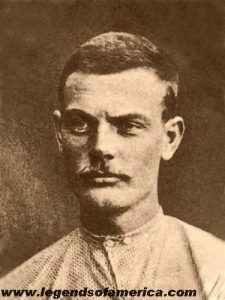

Frank James was slighter than his brother, with light hair, blue eyes, and a ragged, reddish mustache. Frank surrendered to Governor Crittenden at Jefferson City in October 1882, taking off his revolvers and saying that no man had touched them but himself since 1861. He was sentenced to the penitentiary for life but later pardoned, as he was thought to be dying of consumption. At this writing, he is still alive, somewhat old and bent now, but leading a quiet and steady life and showing no disposition to return to his old ways. He is sometimes seen around the race tracks, where he does little talking. Frank James has had many apologists, and his life should be considered in connection with the environments in which he grew up. He killed many men, but he was never as cold and cruel as Jesse, and of the two, he was the braver man, men say, who knew them both. He never was known to back down under any circumstances.

The fate of the Younger boys was much mingled with that of the James boys, but the end of the careers of the former came more dramatically. The wonder is that both parties should have clung together so long, for it is certain that Cole Younger once intended to kill Jesse James and one night, he came near killing George Shepherd through malicious statements Jesse James had made to him about the latter. Shepherd met Cole at the house of a friend named Hudspeth in Jackson County, and their host put them in the same bed that night for want of better accommodations. “After we lay down,” said Shepherd later, in describing this, “I saw Cole reach up under his pillow and draw out a pistol, which he put beside him under the cover. Not to be taken unawares, I at once grasped my own pistol and shoved it down under the covers beside me. Were it to save my life, I couldn’t tell what reason Cole had for becoming my enemy. We talked very little but just lay there watching each other. He was behind me on the front side of the bed, and during the entire night, we looked into each other’s eyes and never moved. It was the most wretched night I ever passed in my life.” So much may, at times, be the price of being “bad.” By good fortune, they did not kill each other, and the next day Cole told Shepherd that he had expected him to shoot on sight, as Jesse James had said he would. Explanations then followed. It nearly came to a collision between Cole Younger and Jesse James later, for Cole challenged him to fight, and it was only with difficulty that their friends accommodated the matter.

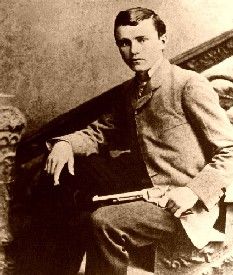

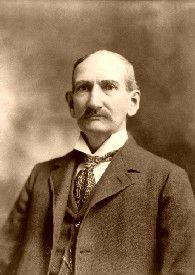

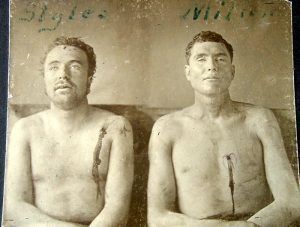

The James-Younger Gang – Left to right: Cole” Younger,

Jesse Woodson James, Bob Younger, and Frank James.

The history of the Younger Boys is tragic all the way through. Their father was assassinated, and their mother was forced to set fire to her own house and destroy it under penalty of death; three sisters were arrested and confined in a barracks at Kansas City, which during a high wind fell in, killed two of the girls and crippled the other. John Younger was a murderer at the age of fourteen, and how many times Cole Younger was a murderer, with or without his wish, will never be known. He was shot three times in one fight in guerrilla days, and probably few bad men ever carried off more lead than he.

The story of the Northfield bank robbery in Minnesota, which ended so disastrously for the bandits who undertook it, is interesting as it shows what brute courage and, indeed, what fidelity and fortitude may sometimes be shown by dangerous specimens of bad men. The purpose of the robbery was criminal, its carrying out was attended with murder, and the revenge for it came sharp and swift. In all the annals of desperadoes, there is not a battle more striking than this, which occurred in a sleepy and contented little village in the quiet northern farming country, where no one for a moment dreamed that the bandits of the rumored bloody lands along the Missouri River would ever trouble themselves to come. The events immediately connected with this tragedy, the result of which was the Younger gang’s ending, were as described here.

Bill Chadwell, alias Styles, a James boys’ gang member, had formerly lived in Minnesota. He drew a pleasing picture of the wealth of that country and the ease with which bandit methods could obtain it. Cole Younger was opposed to going so far from home but was overruled. He finally joined the others — Frank and Jesse James, Clell Miller, Jim and Bob Younger, Charlie Pitts and Bill Chadwell. After looking over the country, they went to Minnesota by rail, purchased good horses, and prepared to raid the little town of Northfield in Rice County. They carried their enterprise into effect on September 7, 1876, using methods with which earlier experience had made them familiar. They rode into the middle of the town and opened fire, ordering everyone off the streets. Jesse James, Charlie Pitts, and Bob Younger entered the bank, where they found cashier J. L. Haywood with two clerks, Frank Wilcox and A. E. Bunker.

Bunker started to run, and Bob Younger shot him in the shoulder. They ordered Haywood to open the safe, but he bluntly refused, even though they slightly cut him in the throat to enforce obedience. Firing now began from the citizens on the street, and the bandits in the bank hurried in their work, contenting themselves with such loose cash as they found in the drawers and on the counter. As they started to leave the bank, Haywood motioned toward a drawer as if to find a weapon. Jesse James turned and shot him through the head, killing him instantly.

These three bandits then sprang out into the street. They were met by the fire of Doctor Wheeler and several other citizens, Hide, Stacey, Manning, and Bates. Doctor Wheeler was across the street in an upstairs room, and as Bill Chadwell undertook to mount his horse, Wheeler fired and shot him dead. Manning fired at Clell Miller, who had mounted, and shot him from his horse.

Cole Younger was by this time ready to retreat, but he rode up to Miller and removed his belt and pistols from his body. Manning fired again and killed the horse behind which Bob Younger was hiding, and an instant later, a shot from Wheeler struck Bob in the right elbow. Although this arm was disabled, Bob shifted his pistol to his left hand and fired at Bates, cutting a furrow through his cheek but not killing him. About this time, a Norwegian by the name of Gustavson appeared on the street and not halting at the order to do so. He was shot through the head by one of the bandits, receiving a wound from which he died a few days later. The gang then began to scatter and retreat. Jim Younger was on foot and was wounded. Cole rode back up the street and took the wounded man on his horse behind him. The entire party then rode out of town to the west, not one of them escaping without severe wounds.

As soon as the bandits had departed, the news was sent by telegraph, notifying the surrounding country of the robbery. Sheriffs, policemen, and detectives rallied in such numbers that the robbers were hard put to it to escape alive. A state reward of $1,000 for each was published, and all of lower Minnesota organized itself into a determined manhunt. The gang undertook to get over the Iowa line, and they managed to keep away from their pursuers until the morning of the 13th, a week after the robbery. The six survivors were surrounded on that day in a strip of timber. Frank and Jesse James broke through, riding the same horse. They were fired upon, a bullet striking Frank James in the right knee and passing through Jesse’s right thigh. Nonetheless, the two got away, stole a horse apiece that night, and passed on to the Southwest. They rode bareback and now and again enforced a horse trade with a farmer or livery-stable man. They got down near Sioux Falls and met Doctor Mosher, whom they compelled to dress their wounds and furnish them with horses and clothing. Later, their horses gave out, and they hired a wagon and kept on. Their escape seems incomprehensible, yet it is the case that they got quite clear, finally reaching Missouri.

Of the other bandits, there were left Cole, Jim and Bob Younger, and Charlie Pitts, and after these, a large number of citizens followed close. Despite the determined pursuit, they kept out of reach for another week. On the morning of September 21, two weeks after the robbery, they were located in the woods along the Watonwan River, not far from Madelia. Sheriff Glispin hurriedly got together a posse and surrounded them in a patch of timber not over five acres in extent. In a short time, more than one hundred and fifty men were about this cover, but although they kept up firing, they could not drive out the concealed bandits.

Sheriff Glispin called for volunteers, and Colonel Vaught, Ben Rice, George Bradford, James Severson, Charles Pomeroy, and Captain Murphy moved into the cover. As they advanced, Charlie Pitts sprang out from the brush and fired point-blank at Glispin. At the same instant, the latter also fired and shot Pitts, who ran a short distance and fell dead. Then Cole, Bob, and Jim Younger stood up and opened fire as best they could, all of the men of the storming party returning their fire. Murphy was struck in the body by a bullet, and his life was saved by his pipe, which he carried in his vest pocket. Another posse member had his watch blown to pieces by a bullet. The Younger boys gave back a little, but this brought them within sight of those surrounding the thicket, so they retreated again close to the line of the volunteers. Cole and Jim Younger were now badly shot. With his broken right arm, Bob stood his ground, the only one able to continue the fight, and kept his revolver going with his left hand. The others handed him their revolvers after his own was empty. The firing from the posse continued, and at last, Bob called out to them to stop as his brothers were all shot to pieces. He threw down his pistol and walked forward to the sheriff, to whom he surrendered. Bob always spoke with respect for Sheriff Glispin as a fighter and peace officer. One of the farmers drew up his gun to kill Bob after he had surrendered, but Glispin told him to drop his gun or he would kill him.

It is doubtful if any set of men ever showed more determination and more ability to stand punishment than these misled outlaws. Bob Younger was hurt less than any of the others. His arm had been broken at Northfield two weeks before, but he was wounded but once, slightly in the body, out of all the shots fired at him while in the thicket. Cole Younger had a rifle bullet in the right cheek, which paralyzed his right eye. He had received a .45 revolver bullet through the body and also had been shot through the thigh at Northfield. He received 11 different wounds in the fight, or 23 bad wounds in all, enough to have killed a half dozen men. Jim’s case seemed even worse, for he had eight buckshot and a rifle bullet in his body. He had been shot through the shoulder at Northfield, and nearly half his lower jaw had been carried away by a heavy bullet, a wound which caused him intense suffering. Bob was the only one able to stand on his feet.

Of the two men killed in town, Clell Miller and Bill Chadwell, the former had a long record in bank robberies; the latter, guide in the ill-fated expedition to Minnesota, was a horse thief of considerable note at one time in lower Minnesota.

The prisoners were placed in jail at Faribault, the county seat of Rice County, and in a short time, the Grand Jury returned true bills against them, charging them with murder and robbery. Court convened on November 7, Judge Lord being on the bench. All of the prisoners pleaded guilty, and the court ordered that each should be confined in the state penitentiary for the period of his natural life.

The later fate of the Younger boys may be read in the succinct records of the Minnesota State Prison at Stillwater:

“Thomas Coleman Younger, sentenced November 20, 1876, from Rice County under a life sentence for the crime of Murder in the first degree. Paroled July 14, 1901. Pardoned February 4, 1903, on condition that he leave the State of Minnesota and never exhibit himself in public in any way.

James Younger was sentenced on November 20, 1876, from Rice County under a life sentence for the crime of Murder in the first degree. Paroled July 13, 1901. He shot himself with a revolver in St. Paul, Minnesota, and died at once from the wound inflicted on October 19, 1902.

Robert Younger was sentenced on November 20, 1876, from Rice County under a life sentence for the crime of Murder in the first degree. He died on September 16, 1889, of phthisis.”

The James boys almost miraculously escaped, traveled clear across the State of Iowa, and got back to their old haunts. They did not stop but kept going until they got to Mexico, where they remained for some time. However, they did not take their warning, and some of their most desperate train robberies were committed long after the Younger boys were in the penitentiary.

Given the bloody careers of all these men, it is to be said that the law has been singularly lenient with them. Yet the Northfield incident was conclusive and was the worst backset ever received by any gang of bad men, unless, perhaps, that was the defeat of the Dalton Gang at Coffeyville, Kansas, some years later, the story of which is given in Badmen of the Indian Nations.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2023.

Go To Next Chapter – Bad Men Of The Indian Nations

About the Author: Excerpted from the book The Story of the Outlaw: A Study of the Western Desperado, by Emerson Hough; Outing Publishing Company, New York, 1907. This story is not verbatim, as it has been edited for clerical errors and updated for the modern reader. Emerson Hough (1857–1923) was an author and journalist who wrote factional accounts and historical novels of life in the American West. His works helped establish the Western as a popular genre in literature and motion pictures. For years, Hough wrote the feature “Out-of-Doors” for the Saturday Evening Post and contributed to other major magazines.

Other Works by Emerson Hough:

The Story of the Outlaw – A Study of the Western Desperado – Entire Text