The Sand Creek Massacre, occurring on November 29, 1864, was one of the most infamous incidents of the Indian Wars. Initially reported in the press as a victory against a bravely fought defense by the Cheyenne, later eyewitness testimony conflicted with these reports, resulting in a military and two Congressional investigations into the events.

Starting in the 1850s, the gold and silver rush in the Rocky Mountains brought thousands of white settlers into the mountains and the surrounding foothills. Dislocating and angering the Cheyenne and Arapaho who lived on the land, the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush in 1858 brought the tension to a boiling point.

The Indians soon began to attack wagon trains, mining camps, and stagecoach lines, a practice that increased during the Civil War, when the number of soldiers in the area was significantly decreased. This led to what became known as the Colorado War of 1863-1865.

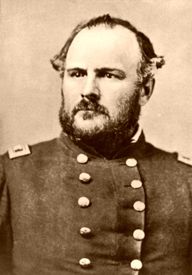

John Milton Chivington (1821 – 1894). A hero in the Battle of Glorieta Pass in New Mexico and the infamous Commander of the U.S. Army at the Sand Creek Massacre.

As the violence between the Native Americans and the miners increased, territorial governor John Evans sent a Voluntary Militia commander Colonel John Chivington to quiet the Indians. Though once a clergy member, Chivington’s compassion did not extend to the Indians, and his desire to extinguish them was well known. Evans also issued two orders, the first required “friendly Indians” to gather at specific camps and threatened violence against those who didn’t comply. The second called for citizens to “kill and destroy” Native Americans who were deemed hostile by the state.

In the spring of 1864, while the Civil War raged in the east, Chivington launched a campaign of violence against the Cheyenne and their allies, his troops attacking all Indians and razing their villages. The Cheyenne, joined by neighboring Arapaho, Sioux, Comanche, and Kiowa in Colorado and Kansas, went on the defensive warpath.

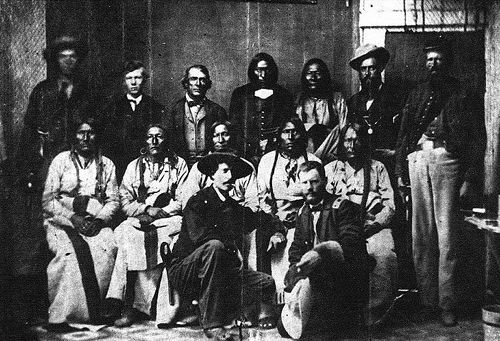

Soon, Evans and Chivington reinforced their militia, raising the Third Colorado Cavalry of short-term volunteers who referred to themselves as the “Hundred Dazers.” After a summer of scattered small raids and clashes, the Cheyenne and Arapaho were ready for peace. As a result, the Indian representatives met with Evans and Chivington at Camp Weld outside of Denver on September 28, 1864. Though no treaties were signed, the Indians believed that by reporting and camping near army posts, they would be declaring peace and accepting sanctuary.

However, on the day of the “peace talks,” Chivington received a telegram from General Samuel Curtis (his superior officer) informing him that “I want no peace till the Indians suffer more… No peace must be made without my directions.”

Unaware of Curtis’s telegram, Black Kettle and some 550 Cheyenne and Arapaho, having made their peace, traveled south to set up camp on Sand Creek under the promised protection of Fort Lyon. Those who remained opposed to the agreement headed North to join the Sioux.

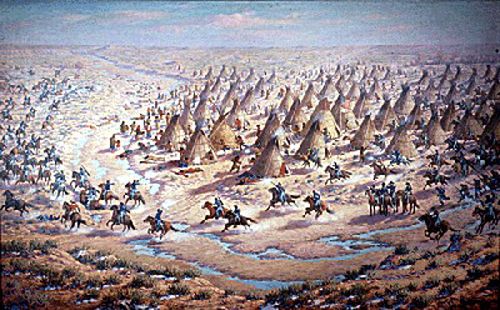

Knowing that the Indians had surrendered, Chivington led his 700 troops, many of them drinking heavily, to Sand Creek and positioned them, along with their four howitzers, around the Indian village. The ever trusting Black Kettle raised both an American and a white flag of peace over his tepee.

However, Chivington ignored the symbol of peace and surrender, raising his arm for the attack. An easy victory at hand, cannons and rifles began to pound upon the camp as the Indians scattered in panic. The frenzied soldiers began to charge, hunting down men, women, and children, shooting them unmercifully. A few warriors managed to fight back, allowing some camp members to escape across the stream.

One man, Silas Soule, a Massachusetts abolitionist, refused to follow Colonel Chivington’s orders. He did not allow his cavalry company to fire into the crowd.

The troops kept up their indiscriminate assault for most of the day, during which numerous atrocities were committed. One lieutenant was said to have killed and scalped three women and five children who had surrendered and screamed for mercy. Finally breaking off their attack, they returned to the camp killing all the wounded they could find before mutilating and scalping the dead, including pregnant women, children, and babies. Before leaving, they plundered the teepees and divided up the Indians’ horse herd.

When the attack was over, as many as 150 natives lay dead, most of which were old men, women, and children. In the meantime, the cavalry lost only nine or ten men, with about three dozen wounded. Black Kettle and his wife followed the others up the stream bed, his wife being shot several times but somehow managed to survive.

The survivors, over half of whom were wounded, sought refuge in the camp of the Cheyenne Dog Warriors (who had remained opposed to the peace treaty) at the Smoky Hill River. Many Indians joined the Dog Soldiers, deciding there could be no successful negotiations with the white men and waging war against them. Indeed, the Sand Creek Massacre is cited as a critical cause of the Little Big Horn battle, as many Cheyenne warriors devoted their lives to war against the U.S.

The Colorado volunteers returned to Denver to receive a hero’s welcome, exhibiting their scalps. Initially, the press reported the battle as a victory against a bravely-fought defense by the Cheyenne. However, within weeks, eyewitnesses offered conflicting testimony, leading to a military investigation and two Congressional investigations into the events. Silas Soule was eager to testify against Chivington. However, after he testified, Soule was murdered by Charles W. Squires, a murder believed to have been ordered by Chivington.

As the details came out, the U.S. public was shocked by the brutality of the massacre. The congressional investigation subsequently determined the crime to be a “sedulously and carefully planned massacre.” When asked at the military inquiry why children had been killed, one of the soldiers quoted Chivington as saying, “nits make lice.” Though Chivington was denounced in the investigation and forced to resign, neither he nor anyone else was ever brought to justice for the massacre.

While the Sand Creek Massacre outraged easterners, it pleased many people in Colorado Territory. Chivington later appeared on a Denver stage where he regaled delighted audiences with his war stories and displayed 100 Indian scalps, including the hairs of women.

As word of the massacre spread among the Indians of the southern and northern plains, their resolve to resist white encroachment stiffened. An avenging wildfire swept the land, and peace returned only after a quarter of a century.

Through the years, the area of the Sand Creek Massacre has continued to be visited and commemorated. An aging John Chivington returned to the area in 1887, and in 1908 Veterans of the Colorado Regiments planned a reunion at the site. In August of 1950, the Colorado Historical Society assisted residents and the Eads and Lamar Chambers of Commerce in placing a marker atop the bluff at the Dawson South Bend. Sand Creek descendants remain active in tribal communities in Montana, Oklahoma, and Wyoming – and Council Representatives continue to work alongside the National Park Service. However, throughout, it has remained a controversial incident. And specifically, in Colorado, it has traditionally been held as a founding victory for Colorado.

The Sand Creek Massacre was made a National Historic site on August 2, 2005, almost a decade after Congress mandated the action in 1998. It has been delayed and troubled over the years due to controversy and disagreement but was finally pulled together for an accurate remembrance of that horrible event in American History.

In November of 2014, the Smithsonian Magazine pre-released an article for its December edition entitled “The Horrific Sand Creek Massacre Will Be Forgotten No More” stating, “The opening of a national historic site in Colorado helps restore to public memory one of the worst atrocities ever perpetrated on Native Americans.”

The two orders issued by territorial governor John Evans in 1864 that helped set the stage for the massacre were never officially rescinded when Colorado became a state. That blight in the record was corrected when Colorado Governor Jared Polis officially rescinded the two proclamations on August 17, 2021.

Contact Information:

Sand Creek National Historic Site

P.O. Box 249

Eads, Colorado 81036

719-438-5916

In September, Black Kettle (seated center) and other Cheyenne chiefs conclude successful peace talks with Major Edward W. Wynkoop (kneeling with hat) at Fort Weld, Colorado. 1864. Based on the promises made at this meeting, Black Kettle led his band back to the Sand Creek reservation, where they were massacred in late November.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2022.

Also See:

Chief Black Kettle – A Peaceful Leader

Washita Battlefield National Historic Site, Oklahoma