The Great Sioux War of 1876, also known as the Black Hills War, was a series of battles and negotiations which occurred in 1876 and 1877 between the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and the United States. It began after Gold had been discovered in the Black Hills, settlers began to encroach onto Native American lands. The U.S. Government then wanted to obtain ownership of the area, and the Sioux and Cheyenne refused.

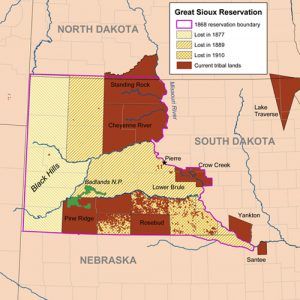

Red Cloud’s War of 1866-68 clearly established the dominance of the Oglala Sioux over U.S. forces in northern Wyoming and southern Montana east of the Bighorn Mountains. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 between the Sioux nation and the United States set aside a portion of the Sioux territory as the Great Sioux Reservation. This included the Black Hills region for their exclusive use. It also provided for unceded territory for Cheyenne and Lakota hunting grounds. This territory was called unceded in recognition that although the United States did not recognize Sioux ownership of the land, neither did it deny that the Sioux had hunting rights there.

Sioux Reservation Map, courtesy Wikipedia

The treaty also established a reservation in Dakota Territory wherein “the United States now solemnly agrees that no persons except those herein designated and authorized so to do… shall ever be permitted to pass over, settle upon, or reside in the territory described in this article … and henceforth the [Indians] will, and do, hereby relinquish all claims or right in and to any portion of the United States or Territories, except such as is embraced within the limits aforesaid, and except as hereinafter provided.” This provision clearly established the solemn rights of the Sioux to perpetual ownership of the reservation.

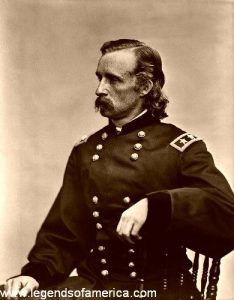

In the spring of 1874, General Philip H. Sheridan, commanding the Military Division of the Missouri, directed his subordinate, Brigadier General Alfred H. Terry, commanding the Department of Dakota, to send a reconnaissance party into the Black Hills to ascertain the suitability of establishing an Army garrison there.

This reconnaissance party, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer, not only determined the adequacy of the ground for a garrison but found evidence of gold. The news flashed through the nation, triggering a gold rush to the Black Hills of what is now South Dakota. The difficulty was that the Black Hills region was squarely inside the territory reserved to the Sioux in the treaty of 1868.

But no American government, no matter how progressive, would have attempted to restrain such a great number of citizens in their pursuit of happiness (as manifested by their dreams of gold). Thus, the predicament faced by President Ulysses S. Grant was that he could not prevent Americans from entering the Black Hills; at the same time, he could not legally allow them to go there.

In May 1875, Sioux delegations headed by Spotted Tail, Red Cloud, and Lone Horn traveled to Washington, D.C. to persuade President Ulysses S. Grant to honor existing treaties and stem the flow of miners into their territory. Grant wanted to pay the tribes $25,000 for the land and have them relocate to Indian Territory (in present-day Oklahoma). But the Indians refused, with Spotted Tail stating:

“You speak of another country, but it is not my country; it does not concern me, and I want nothing to do with it. I was not born there… If it is such a good country, you ought to send the white men now in our country there and let us alone.”

Although the chiefs were unsuccessful in finding a peaceful solution, they did not join Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull in warfare.

Rationalizing an excuse for war with the Sioux seemed to be Grant’s only choice to resolve the matter. If the government fought the Sioux and won, the Black Hills would be ceded as a spoil of war. But Grant chose not to fight the Sioux who remained on the reservations. Rather, he was determined to attack that portion of the Sioux roaming in the unceded land on the pretext that they were committing atrocities on settlers beyond the Indians’ borders. Accordingly, Grant ordered the Bureau of Indian Affairs to issue an ultimatum to the Indians to return voluntarily to their reservation by January 31, 1876, or be forced there by military action. Those roamers outside the reservation, most of whom ignored the ultimatum.

After the deadline passed, the Indians were turned over to the War Department. On February 8, 1876, General Sheridan ordered Generals George Crook and Alfred Terry to commence campaigns against the “hostiles,” thus starting The Great Sioux War of 1876.

In the next two years, several battles would be fought, including:

Battle of Powder River – March 17, 1876, Montana

Battle of Prairie Dog Creek – June 9, 1876, Wyoming

Battle at Warbonnet Creek – July 17, 1876, Nebraska

Battle of Rosebud Creek – June 17, 1876, Montana

Battle of the Little Bighorn – June 25, 1876, Montana

Battle of Slim Butte – September 9, 1876, South Dakota

Battle of Glendive Creek – October 10, 1876, Montana

Battle of Cedar Creek – October 21, 1876, Montana

Dull Knife Fight – November 25, 1876, Wyoming

Battle of Wolf Mountain – January 8, 1877, Montana

Battle of Little Muddy Creek – May 7, 1877, Montana

The continuous military campaigns and the intensive diplomatic efforts finally began to yield results in the early spring of 1877 as large numbers of northern bands began to surrender.

A large number of Northern Cheyenne, led by Dull Knife and Standing Elk, surrendered at the Red Cloud Agency in April 1877 and were sent to Indian Territory the following month. Roman Nose and Touch the Clouds surrendered at the Spotted Tail Agency, and Crazy Horse surrendered with his band at Red Cloud on May 5th.

While many of the Sioux bands surrendered at the various agencies, Chief Sitting Bull led a large contingent across the border into Canada. However, they, too finally returned and surrendered in the summer of 1881.

The Great Sioux War contrasted sharply with Red Cloud’s War fought a decade earlier, when Sioux leaders had wide support from their bands. But, during this war, nearly two-thirds of the Sioux had settled on reservations, were accepting rations and subsistence, and did not support or participate in the fighting.

The deep political divisions within the tribe continued for the next decade, and non-agency bands joined in the rise of the Ghost Dance movement in 1889–90.

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated June 2021.

Also See:

Indian Wars, Battles & Massacres

Winning The West: The Army In The Indian Wars

Sources:

Collins, Charles D., Jr.; Combat Studies Institute, United States Dept. of Defense, 2006

Wikipedia