~~

Camp Union – Keeping Kansas City Safe From Confederates

General “Jo” Shelby and His Great Raid through Missouri

General Order #11 – Devastating Northwest Missouri

Liberty Arsenal – Raided by the Pro-Slavery Faction

Campaigns:

Marmaduke’s Missouri Expeditions in the Civil War

Operations North of Boston Mountains

Operations at the Ohio and Mississippi River Confluence of the Civil War

During the Civil War, Missouri was a hotly contested border state populated by Union and Confederate sympathizers.

The French introduced slavery west of the Mississippi River in the 18th century, and Southerners found it easy to transplant their system of chattel slavery. Early on, slavery thrived along the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, where the agricultural potential made slavery economically viable.

Even before the Louisiana Purchase, frontier migrants from the Upper South, the most famous being Daniel Boone, crossed the Mississippi River to settle in Spanish-controlled Upper Louisiana, where they found a well-watered forested country reminding them of their ancestral homelands in Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee, and ideally suited for the establishment of Southern agriculture and customs.

The Missouri Compromise prohibited slavery in the unorganized territory of the Great Plains (dark green) and permitted it in Missouri (yellow) and the Arkansas Territory (lower blue area).

Missouri entered the Union in 1821 as a slave state following the Missouri Compromise of 1820, in which it was agreed that no state north of Missouri’s southern border with Arkansas could enter the Union as a slave state. Maine entered the Union as a free state in the compromise to balance Missouri.

In 1854 the Kansas-Nebraska Act nullified the Missouri Compromise and said Kansas and Nebraska could decide on their own whether to enter as a free or slave state. The result was a de facto war between pro-slavery residents of Missouri, called Border Ruffians, and Kansas Free Staters to influence how Kansas entered the Union.

Despite its initially southern nature, Missouri changed rapidly in the decade before the war, mainly due to immigration from the northern and eastern states, Germany and Ireland. By 1860, 30 percent of Missourians hailed from the northeastern states or foreign countries. Economic forces also linked Missouri to northern industrial centers, but none were more critical than railroads. Missouri caught the railroad building mania late. A network of 7,000 miles of rails already connected Chicago, New York, and Boston by 1859 when the Hannibal and St. Joseph, Missouri’s first rail line, was completed. By 1860, Missouri boasted 800 miles of railroad. St. Louis, the state’s largest city, river transportation hub, and industrial center, had a network of railroads radiating into Missouri’s rich agricultural and mineral interior lands.

The controversy surrounding slavery’s westward expansion emerged with the very founding of the state. It ignited the flashpoints that drove the nation to war, including the Missouri Compromise, the Dred Scott case, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and the Kansas-Missouri Border War. As the epicenter of the issue of slavery’s expansion and the site of a violent and prolonged conflict, Missouri is one of the most critical regions for understanding the causes of the Civil War. Yet, Missouri’s distance from the primary theater of war and the irregular, unconventional, and brutal nature of the conflict in the state drove Missouri’s Civil War into the margins of broader Civil War history.

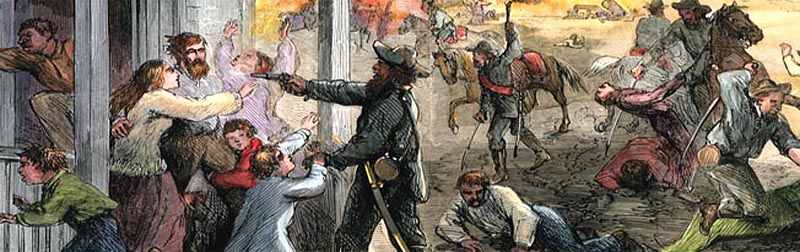

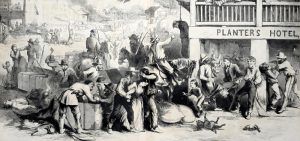

The Border War between Kansas and Missouri, often called Bleeding Kansas, was a series of violent political confrontations involving anti-slavery free-staters and pro-slavery “Border Ruffian” elements. Most of these conflicts involved attacks and murders of individuals on both sides, with the Sacking of Lawrence by pro-slavery forces and the Pottawatomie Massacre by John Brown being the most notable. The Border War occurred in the Kansas Territory and the neighboring towns of Missouri between 1854 and 1861. At the heart of the conflict was whether Kansas would enter the Union as a Free or slave state. As such, Bleeding Kansas was a proxy war between Northerners and Southerners over the issue of slavery in the United States. The term “Bleeding Kansas” was coined by Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune, and organized violence took its turn in Bleeding Kansas and along Missouri’s western border in a small preview of greater horrors yet to come.

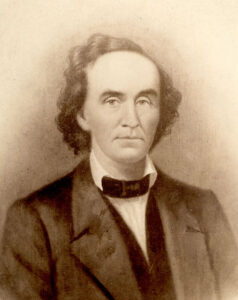

In the election of 1860, Missouri’s newly elected governor was Claiborne Fox Jackson, a career politician and an ardent supporter of the South. Jackson campaigned as favoring a conciliatory program on issues that divided the country.

Less than two months after President Abraham Lincoln’s election, South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union — six more, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas — followed suit by February 1861. But the newborn Confederacy was vulnerable in many ways. It claimed only 10 percent of the nation’s white population and five percent of its industrial establishment. And not all the slave states had come on board. Missouri was among eight Upper South border states that had not declared. The stakes were high for winning the allegiance of these states, which accounted for more than half the population of the South and produced half of the region’s horses and mules, three-fifths of its livestock and cereal crops, and three-quarters of its industrial capability.

When the war began in 1861, it became clear that control of the Mississippi River and the burgeoning economic hub of St. Louis, Missouri, would make Missouri a strategic territory in the Trans-Mississippi Theater.

Despite their initial reluctance to sever ties with the Union, Missourians, fundamentally Southern in culture and heritage, constituted most of the state’s population. Identity with the South was a powerful and pervasive force in Missouri society and politics.

At that time, Missouri’s Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson changed his tactics from those he had campaigned on and immediately began working behind the scenes to promote Missouri’s secession. In addition to planning to seize the federal arsenal at St. Louis, Jackson conspired with senior Missouri bankers to illegally divert money from the banks to arm state troops, a measure that the Missouri General Assembly had so far refused to take.

Afterward, Missouri maintained dual governments, sent armies, generals, and supplies to both sides, and endured a bloody neighbor-against-neighbor intrastate war within the larger national war.

Claimed by both North and South, Missouri held a liminal status between Union and Confederate, with combatants fighting conventional battles and guerrilla war. The guerrilla war predominated throughout the war and shifted the struggle from the battlefield to the home front, blurring the line between combatant and noncombatant and drawing civilians into the conflict.

The war in Missouri was continuous between 1861 and 1865, with battles and skirmishes in all areas of the state.

The first major Civil War battle west of the Mississippi River took place on August 10, 1861, at Wilson’s Creek, Missouri, while the most significant battle west of the Mississippi River was the Battle of Westport in Kansas City in 1864.

Counting minor actions and skirmishes, Missouri saw more than 1,200 distinct engagements within its boundaries; only Virginia and Tennessee exceeded this total.

The struggle in Missouri was one of the most prolonged and violent conflicts in the 19th century, with battles and bloodshed beginning for six years before the Civil War began and continuing to a lesser extent once the Civil War was over.

The war ended in April 1865, but the struggle for Missouri continued as civilians and politicians wrestled over Missouri’s Reconstruction. The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 and the 13th Amendment of 1865 officially abolished slavery, the foundation of southern society, forcing Missourians to restructure their social, economic, and political worlds. Newly freed African Americans, while gaining new rights and freedoms in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, continued to be the targets of discriminatory violence at the hands of white men who opposed their newfound status. Many guerrilla fighters pursued the same activities during Reconstruction as during the war, continuing their exploits as thieves and murderers. Missourians reordered society and rebuilt their devastated communities after an exceedingly destructive war. Yet, many of the scars of war lay hidden beneath the surface of postwar society as survivors privately mourned their relatives, cared for the wounded, and sought consolation in war memorials and commemorative societies and organizations.

The Union Army stated, “Missouri was one of the last and one of the first states to feel the curse of Civil War. During the contest, she furnished to the Federal government a total of 109,111 men, exclusive of the militia she maintained to keep peace within her borders and protect her people from the raids of the guerrillas, Jayhawkers.

By the war’s end in 1865, nearly 110,000 Missourians had served in the Union Army and at least 40,000 in the Confederate Army; many had also fought with bands of pro–Confederate partisans known as “bushwhackers.”

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated June 2023.

Also See:

Civil War Timeline & Leading Events

Sources:

Essential Civil War Curriculum

Missouri State Parks

State Historical Society of Missouri

Thomas Legion

Wikipedia