“By virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free.”

— President Abraham Lincoln, January 1, 1863

Jump To:

Emancipation Proclamation Transcription

The Emancipation Proclamation – An Act of Justice (By John Hope Franklin, Prologue Magazine, 1993)

The 13th Amendment to the Constitution (Text)

History of the passing of the 13th Amendment (by John G. Hay and John Nicolay, 1889)

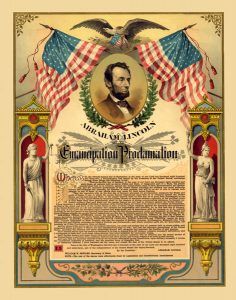

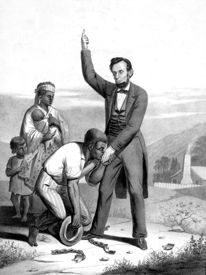

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, as the nation approached its third year of bloody Civil War. The proclamation declared “that all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.”

Despite this expansive wording, the Emancipation Proclamation was limited in many ways. It applied only to states that had seceded from the Union, leaving slavery untouched in the loyal border states. It also expressly exempted parts of the Confederacy that had already come under Northern control. Most importantly, the freedom it promised depended upon the Union’s military victory.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation, it captured the hearts and imagination of millions of Americans and fundamentally transformed the character of the Civil War. After January 1, 1863, every advance of federal troops expanded the domain of freedom. Moreover, the Proclamation announced the acceptance of black men into the Union Army and Navy, enabling the liberated to become liberators. By the end of the war, almost 200,000 black soldiers and sailors had fought for the Union and freedom.

From the first days of the Civil War, slaves had acted to secure their own liberty. The Emancipation Proclamation confirmed their insistence that the war for the Union must become a war for freedom. It added moral force to the cause of the Union and strengthened it militarily and politically. As a milestone along the road to slavery’s final destruction, the Emancipation Proclamation has assumed a place among the great documents of human freedom.

The original of the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, is in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. With the text covering five pages the document was originally tied with narrow red and blue ribbons, which were attached to the signature page by a wafered impression of the seal of the United States. Most of the ribbon remains; parts of the seal are still decipherable, but others have worn off.

The document was bound with other proclamations in a large volume preserved for many years by the Department of State. When it was prepared for binding, it was reinforced with strips along the center folds and then mounted on a still larger sheet of heavy paper. Written in red ink on the upper right-hand corner of this large sheet is the number of the Proclamation, 95, given to it by the Department of State long after it was signed. With other records, the volume containing the Emancipation Proclamation was transferred in 1936 from the Department of State to the National Archives of the United States.

Lincoln signed his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, stating that all slaves would be free in the rebellious states if the rebels did not end hostilities and rejoin the Union by January 1, 1863.

Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation Transcription

By the President of the United States of America:

A Proclamation.

Whereas, on the twenty-second day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-two, a proclamation was issued by the President of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, to wit:

“That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

“That the Executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State, or the people thereof, shall on that day be, in good faith, represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such State shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State, and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States.”

Now, therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do, on this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and in accordance with my purpose so to do publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days, from the day first above mentioned, order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States, the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans) Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomack, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth), and which excepted parts, are for the present, left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defense; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known that such persons of suitable condition will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty three, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-seventh.

By the President: Abraham Lincoln

William H. Seward, Secretary of State

The Emancipation Proclamation – An Act of Justice

By John Hope Franklin, Prologue Magazine, 1993

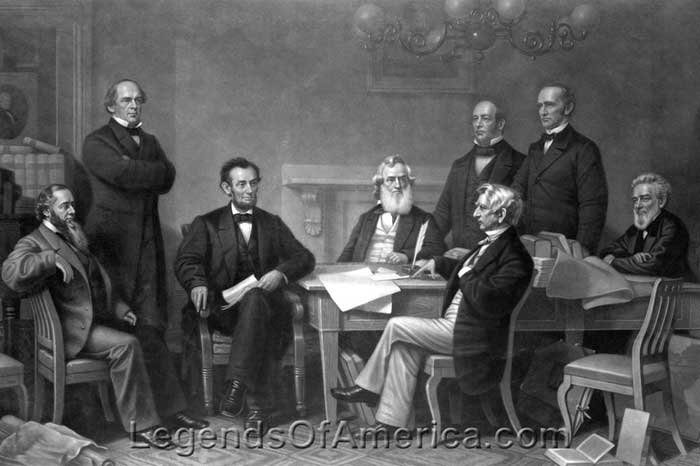

Thursday, January 1, 1863, was a bright, crisp day in the nation’s capital. The previous day had been a strenuous one for President Abraham Lincoln, but New Year’s Day was to be even more strenuous. So he rose early. There was much to do, not the least of which was to put the finishing touches on the Emancipation Proclamation. At 10:45, the document was brought to the White House by Secretary of State William Seward. The President signed it, but he noticed an error in the superscription. It read, “In testimony whereof I have hereunto set my name and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.” The President had never used that form in proclamations, always preferring to say, “In testimony whereof I have hereunto set my hand. . . .” He asked Seward to make the correction, and the formal signing would be made on the corrected copy.

The traditional New Year’s Day reception at the White House began that morning at 11 o’clock. Members of the Cabinet and the diplomatic corps were among the first to arrive. Officers of the Army and Navy arrived in a body at half past 11. The public was admitted at noon, and then Seward and his son Frederick, the Assistant Secretary of State, returned with the corrected draft. The rigid laws of etiquette held the President to his duty for 3 hours, as his secretaries Nicholay and Hay observed. “Had necessity required it, he could, of course, have left such mere social occupation at any moment,” they pointed out, “but the President saw no occasion for precipitancy. On the other hand, he probably deemed it wise that every circumstance of deliberation should attend the completion of this momentous executive act.”

After the guests departed, the President went upstairs to his study for the signing with a few friends. No Cabinet meeting was called, and no attempt was made to have a ceremony. Later, Lincoln told F. B. Carpenter, the artist, that as he took up the pen to sign the paper, his hand shook so violently that he could not write. “I could not for a moment control my arm. I paused, and a superstitious feeling came over me which made me hesitate… In a moment, I remembered that I had been shaking hands for hours with several hundred people, and hence, this is a very simple explanation of the trembling and shaking of my arm.” With a hearty laugh at his own thoughts, the President proceeded to sign the Emancipation Proclamation. Just before he affixed his name to the document, he said, “I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper.”

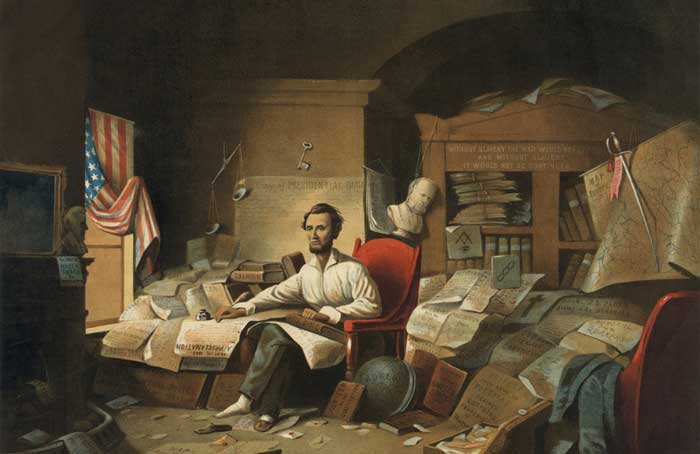

When I made my first serious study of this document, several copies of the December 30 draft were in existence. The copies of Cabinet officers Edward Bates, Francis Blair, William Seward, and Salmon P. Chase were in the Library of Congress. The draft that the President worked with on December 31 and the morning of New Year’s Day is considered the final manuscript draft. The principal parts of the text are written in the President’s hand. The two paragraphs from the Preliminary Proclamation of September 22, 1862, were clipped from a printed copy and pasted onto the President’s draft “merely to save writing.” The superscription and the final closing are in the hands of a clerk in the Department of State. Later in the year, Lincoln presented his copy to the ladies in charge of the Northwestern Fair in Chicago. He told them that he had some desire to retain the paper, “but if it shall contribute to the relief and comfort of the soldiers, that will be better,” he said most graciously. Thomas Bryan purchased it and presented it to the Soldiers’ Home in Chicago, where he was president. The home was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Fortunately, four photographic copies of the original had been made. The official engrossed document is in the National Archives and follows Lincoln’s original copy.

It is worth observing that there was no mention in the final draft of Lincoln’s pet schemes of compensation and colonization, which were in the Preliminary Proclamation of September 22, 1862. Perhaps Lincoln was about to give up on such impracticable propositions. In the Preliminary Proclamation, the President said he would declare slaves in designated territories “thenceforward, and forever free.” In the final draft of January 1, 1863, he was content to say that they “are, and henceforward shall be free.” Nothing had been said in the preliminary draft about the use of blacks as soldiers. In the summer of 1862, the Confiscation Act authorized the President to use blacks in any way he saw fit, and there had been some limited use of them in non-combat activities. In stating in the Proclamation that former slaves were to be received into the armed services, the President believed that he was using congressional authority to strike a mighty blow against the Confederacy.

It was late afternoon before the Proclamation was ready for transmission to the press and others. Earlier drafts had been available, and some papers, including the Washington Evening Star had used those drafts. Still, it was at about 8 p.m. on January 1 that the transmission of the text over the telegraph wires actually began.

Young Edward Rosewater, scarcely 20 years old, had an exciting New Year’s Day. He was a mere telegraph operator in the War Department, but he knew the President and had gone to the White House reception earlier that day and had greeted him. When the President made his regular call at the telegraph office that evening, young Rosewater was on duty and was more excited than ever. He greeted the President and went back to his work. Lincoln walked over to see what Rosewater was sending out. It was the Emancipation Proclamation! If Rosewater was excited, the President seemed the picture of relaxation. After watching the young operator for a while, the President went over to the desk of Tom Eckert, the chief telegraph operator in the War Department, and sat in his favorite chair, where he had written most of the Preliminary Proclamation the previous summer and gave his feet the proper elevation. For him, it was the end of a long, busy, but perfect day.

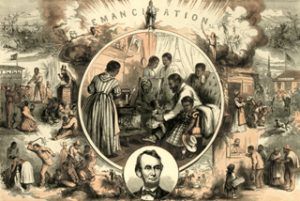

For many others in various parts of the country, the day was just beginning, for the celebrations were not considered official until word was received that the President had actually signed the Proclamation. The slaves of the District of Columbia did not have to wait; however, back in April 1862, Congress passed a law that set them free. Even so, they joined in the widespread celebrations on New Year’s Day. At Israel Bethel Church, Rev. Henry McNeal Turner went out and secured a copy of the Washington Evening Star that carried the text of the Proclamation. Back at the church, Turner waved the newspaper from the pulpit and began to read the document. This signaled unrestrained celebration characterized by men squealing, women fainting, dogs barking, and whites and blacks shaking hands. The Washington celebrations continued far into the night. In the Navy Yard, cannons began to roar and continued for some time.

In New York the news of the Proclamation was received with mixed feelings. Blacks looked and felt happy, one reporter said, while abolitionists “looked glum and grumbled . . . that the proclamation was only given on account of military necessity.” Within a week, however, there were several large celebrations in which abolitionists took part. At Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, the celebrated Henry Ward Beecher preached a commemorative sermon to an overflow audience. “The Proclamation may not free a single slave,” he declared, “but it gives liberty a moral recognition.” There was still another celebration at Cooper Union on January 5. Several speakers, including the veteran abolitionist Lewis Tappan, addressed the overflow audience. Music interspersed the several addresses. Two of the renditions were the “New John Brown Song” and the “Emancipation Hymn.”

A veritable galaxy of leading literary figures gathered in the Music Hall in Boston to take notice of the climax of the fight that New England abolitionists had led for more than a generation. Among those present were John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Francis Parkman, and Josiah Quincy. Toward the close of the meeting, Ralph Waldo Emerson read his “Boston Hymn” to the audience. In the evening, a large crowd gathered at Tremont Temple to await the news that the President had signed the Proclamation. Among the speakers were Judge Thomas Russell, Anna Dickinson, Leonard Grimes, William Wells Brown, and Frederick Douglass. Finally, it was announced that “It is coming over the wire,” and pandemonium broke out! At midnight, the group had to vacate Tremont Temple, and from there, they went to the Twelfth Baptist Church at the invitation of its pastor, Leonard Grimes. Soon, the church was packed, and it was almost dawn when the assemblage dispersed. Frederick Douglass pronounced it a “worthy celebration of the first step on the part of the nation in its departure from the thraldom of the ages.”

The trenchant observation by Douglass that the Emancipation Proclamation was, but the first step could not have been more accurate. Although the Presidential decree would not free slaves in areas where the United States could not enforce the Proclamation, it sent a mighty signal both to the slaves and to the Confederacy that enslavement would no longer be tolerated. An important part of that signal was the invitation to the slaves to take up arms and participate in the fight for their own freedom. That more than 185,000 slaves, as well as free blacks, accepted the invitation indicates that those who had been the victims of thraldom were now among the most enthusiastic freedom fighters.

Meanwhile, no one appreciated better than Lincoln the fact that the Emancipation Proclamation had a quite limited effect in freeing the slaves directly. It should be remembered, however, that in the Proclamation, he called emancipation “an act of justice,” and in later weeks and months, he did everything he could to confirm his view that it was An Act of Justice. And no one was more anxious than Lincoln to take the necessary additional steps to bring about actual freedom. Thus, he proposed that the Republican Party include in its 1864 platform a plank calling for the abolition of slavery by constitutional amendment. When he was “notified” of his re-nomination, as was the custom in those days, he singled out that plank in the platform calling for constitutional emancipation. He pronounced it “a fitting and necessary conclusion to the final success of the Union cause.” Early in 1865, when Congress sent the amendment to Lincoln for his signature, he is reported to have said, “This amendment is a King’s cure for all the evils. It winds the whole thing up.”

Despite the fact that the Proclamation did not emancipate the slaves and surely did not do what the Thirteenth Amendment did in winding things up, it is the Proclamation and not the Thirteenth Amendment that has been remembered and celebrated over the past 130 years. That should not be surprising. Americans seem not to take to celebrating legal documents. The language of such documents is not particularly inspiring, and they are the product of the deliberations of large numbers of people. We celebrate the Declaration of Independence but not the ratification of the Constitution. Jefferson’s words in the Declaration moved the emerging Americans in a way that Madison’s committee of style failed to do in the Constitution.

Thus, almost annually — at least for the first hundred years — each New Year’s Day was marked in many parts of the country by a grand celebration. Replete with brass band, if there was one, an African-American fire company if there were one, and social, religious, and civic organizations, African Americans of the community would march to the courthouse, to some church, or the high school. There, they would assemble to hear the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation, followed by an oration by a prominent person. The speeches varied in character and purpose. Some of them urged African Americans to insist upon equal rights; some of them urged frugality and greater attention to morals, while still others urged their listeners to harbor no ill will toward their white brethren.

As the 50th anniversary of the Proclamation approached, James Weldon Johnson, already a writer of some distinction, was serving a tour of duty as U.S. Consul in Corinto, Nicaragua. His biographer, Eugene Levy, tells us that Johnson, for some time, had considered writing a poem commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. In September 1912, when he read the ceremonies marking the Preliminary Proclamation, he realized that he had only 100 days in which to write the poem. Using all of his spare time, of which there was little, Johnson hammered out “Fifty Years.” There was not enough time to publish it in one of the major literary monthly journals, so he turned to the New York Times, which published it on its editorial page on January 1, 1913.

Addressing his fellow African Americans in the first stanzas, Johnson said:

O Brothers mine, to-day we stand

Where half a century sweeps our ken,

Since God, through Lincoln’s ready hand,

Struck off our bonds and made us men.Just fifty years–a winter’s day–

As runs the history of a race;

Yet, as we look back o’er the day,

How distant seems our starting place!”

Then, in a more assertive tone, making certain that humility did not replace self-confidence, he said:

This land is ours by right of birth,

This land is ours by right of toil

We helped to turn its virgin earth,

Our sweat is in its fruitful soil.To gain these fruits that have been earned,

To hold these fields that have been won,

Our arms have strained, our backs have burned,

Bent bare beneath a ruthless sun.Then should we speak but servile words,

Or shall we hang our heads in shame?

Stand back of new-come foreign hordes,

And fear our heritage to claim?No! stand erect and without fear,

And for our foes let this suffice–

We’ve bought a rightful sonship here,

And we have more than paid the price. . . .That for which millions prayed and sighed

That for which tens of thousands fought,

For which so many freely died,

God cannot let it come to naught.”

In the second half of the Proclamation’s first century, the annual celebrations diminished in extent as well as in fervor. Some celebrants, with an eye on a quick buck, began to promote June 19, the day on which President Abraham Lincoln signed a bill abolishing slavery in the territories. The bill did not apply to Texas, which was a state in the Confederacy, but slick promoters there soon drew attention to that day and persuaded Texans, Oklahomans, and others in the Southwest that this was indeed the day of emancipation. It was never quite clear to me, moreover, why we in Oklahoma celebrated August 4 as well as Juneteenth and January 1, but, clearly the summer months had many advantages over a January observance.

Something else was diluting the celebrations of the anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. It was bad enough that a casual reading of the Proclamation made clear that it did not set the slaves free. It was also clear that neither the Reconstruction amendments nor the legislation and Executive orders of subsequent years had propelled African Americans much closer to real freedom and true equality. The physical violence, the wholesale disfranchisement, and the widespread degradation of blacks in every conceivable form merely demonstrated the resourcefulness and creativity of those white Americans who were determined to deny basic constitutional rights to their black brothers.

Several years before 1963, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People began to use the motto “Free by ’63.” Other groups adopted the motto and focused more attention on the drive for equality. Many leaders were especially sensitive to the significance of the Emancipation Centennial in pointing up racial inequality in American life. On September 22, 1962, when Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York spoke in Washington to mark the opening of the exhibit of the Preliminary Proclamation, “the state’s most treasured possession,” he said, “the very existence of the document stirs our conscience with the knowledge that Lincoln vision of a nation truly fulfilling its spiritual heritage is not yet achieved.”

During the centennial year itself, the United States Commission on Civil Rights presented to the President a report on the history of civil rights, most of which I wrote on contract with the Commission. Knowing that I would be out of the country during most of the centennial year, I published my history of the Emancipation Proclamation as my contribution to the observance.* On Lincoln’s birthday in 1963, President and Mrs. Kennedy received more than a thousand black and white citizens at the White House and presented to each of them a copy of the report of the Civil Rights Commission, called Freedom to the Free. Speaking at Gettysburg later that year, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson said, “Until justice is blind, until education is unaware of race, until opportunity is unconcerned with the color of men’s skins, emancipation will be a proclamation but not a fact.” President Kennedy took note of the absence of equality when he said, “Surely, in 1963, 100 years after emancipation, it should not be necessary for any American citizen to demonstrate in the streets for an opportunity to stop at a hotel or eat at a lunch counter… on the same terms as any other customer.”

Although it is now possible for most African Americans to eat at a lunch counter in most parts of the United States, the extension of these civilities has been accompanied by subtle, yet barbarous forms of discrimination. These forms extend from redlining in the sale of real estate to discrimination in employment to the maladministration of justice. In issuing the Emancipation Proclamation and wording it as he did, Lincoln went as far as he felt the law permitted him to go. In subsequent months he went a bit further, inch by inch, until before his death he was calling for the enfranchisement of some blacks. The difference between Lincoln’s position in 1863 and that of Americans in 1993 is that our leaders in high places seem not to have either the humanity or the courage of Lincoln. The law itself is no longer an obstruction to justice and equality, but it is the people who live under the law who are themselves an obvious obstruction to justice. One can only hope that sooner rather than later we can all find the courage to live under the spirit of the Emancipation Proclamation and under the laws that flowed from its inspiration.

This essay is based on a talk given by John Hope Franklin at the National Archives, January 4, 1993, on the occasion of the 130th anniversary of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation.

*The Emancipation Proclamation (Garden City, NW: Doubleday and Company, 1963; reprint, Arlington Heights, IL: Harlan Davidson, Inc., 1994).

John Hope Franklin has taught at Fisk University, the University of Chicago, and most recently, Duke University, where he is James B. Duke Professor of History Emeritus. Past president of the American Historical Association and the Society of Phi Beta Kappa, his publications include From Slavery to Freedom (1947), The Emancipation Proclamation (1963), and Race and History: Selected Essays, 1938-1988 (1990).

“In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free — honorable alike in what we give, and what we preserve. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best, hope of earth.”

— President Abraham Lincoln, December 1, 1862

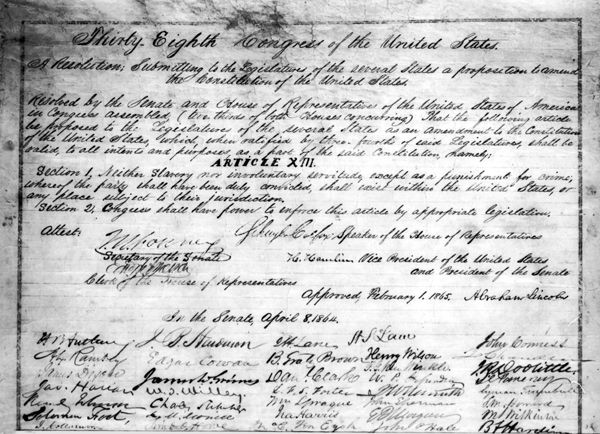

The 13th Amendment to the Constitution

The 13th Amendment to the Constitution declared that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Formally abolishing slavery in the United States, the 13th Amendment was passed by the Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified by the states on December 6, 1865.

The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, along with the 14th Amendment and the 15th Amendment, are the three Reconstruction amendments.

Text of the 13th Amendment

Section 1.

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2.

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

History of the Passing of the 13th Amendment

Written by John G. Hay and John Nicolay, President Lincoln’s private secretaries. This article appeared in The Century, a popular quarterly, Volume 38, Issue 6, Oct 1889.

We have enumerated with some detail the series of radical anti-slavery measures enacted at the second session of the Thirty-seventh Congress, which ended July 17, 1862, the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia; the prohibition of slavery in the national Territories; the practical repeal of the fugitive slave law; and the sweeping measures of confiscation which in different forms decreed, forfeiture of slave property for the crimes of treason and rebellion. When this wholesale legislation was supplemented by the President’s preliminary Emancipation Proclamation of September 22, 1862, and his final edict of freedom of January 1, 1863, the institution had clearly received its coup de grace in all except the loyal border states. Consequently, the third session of the Thirty-seventh Congress, ending March 4, 1863, occupied itself with this phase of the slavery question only to the extent of an effort to implement the President’s plan of compensated abolishment. That effort took practical shape in a bill to give the State of Missouri fifteen million on condition that she would emancipate her slaves. However, the proposition failed, largely through the opposition of a few conservative members from Missouri, and the session adjourned without having, by its legislation, advanced the destruction of slavery.

When Congress met again in December 1863, which was organized by the election of Schuyler Colfax of Indiana as Speaker, the whole situation underwent a further change. The Union arms had been triumphant — Gettysburg had been won, and Vicksburg had capitulated; Lincoln edict of freedom had become an accepted fact; fifty regiments of negro soldiers carried bayonets in the Union armies; Vallandigham had been beaten for governor in Ohio by a hundred thousand majority; the draft had been successfully enforced in every district of every loyal State in the Union. Under these brightening prospects, military and political, the more progressive spirits in Congress took up anew the suspended battle with slavery, which the institution had itself invited by its unprovoked assault on the life of the Government.

The Presidents reference to the subject in his annual message was very brief:

The movements [said he] by State action for emancipation in several of the States not included in the Emancipation Proclamation are matters of profound gratulation. And while I do not repeat in detail what I have heretofore so earnestly urged upon this subject, my general views and feelings remain unchanged; and I trust that Congress will omit no fair opportunity of aiding these important steps to a great consummation.

His language had reference to Maryland, where during the autumn of 1863 the question of emancipation had been actively discussed by political parties, and where at the election of November 4, 1863, a legislature had been chosen to contain a considerable majority pledged to emancipation. More especially did it refer to Missouri, where, notwithstanding the failure of the fifteen million compensation bill at the previous session, a State convention had actually passed an ordinance of emancipation, though with such limitations as rendered it unacceptable to the more advanced public opinion of the State. Prudence was the very essence of President Lincoln’s statesmanship, and he doubtless felt it was not safe for the Executive to venture farther at that time. We are like whalers, he said to Governor Morgan one day, who have been on a long chase: we have at last got the harpoon into the monster, but we must now look how we steer, or with one flop of his tail he will yet send us all into eternity.

Senators and members of the House, especially those representing anti-slavery States or districts, did not need to be so circumspect.

It was doubtless with this consciousness that J. M. Ashley, a Republican representative from Ohio, and James F. Wilson, a Republican representative from Iowa, on the 4th of December, 1863, that being the earliest opportunity after the House was organized, introduced, the former a bill and the latter a joint resolution to propose to the several States an amendment of the Constitution prohibiting slavery throughout the United States. Both the propositions were referred to the Committee on the Judiciary, of which Mr. Wilson was chairman; but before he made any report on the subject it had been brought before the Senate, where its discussion attracted marked public attention.

Senator John B. Henderson, who with rare courage and skill had, as a progressive conservative, made himself one of the leading champions of Missouri emancipation, on the 11th of January, 1864, introduced into the Senate a joint resolution proposing an amendment to the Constitution that slavery shall not exist in the United States.1 It is not probable that either he or the Senate saw any near hope of success in such a measure. The resolution went to the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, where it caused some discussion, but apparently without being treated as a matter of pressing importance. Nearly a month had elapsed when Mr. Sumner also introduced a joint resolution, proposing an amendment that Everywhere within the limits of the United States and of each State or Territory thereof, all persons are equal before the law so that no person can hold another as a slave. He asked its reference to the select committee on slavery, of which he was chairman; but several senators argued that such an amendment properly belonged to the Committee on the Judiciary, and in this reference, Mr. Sumner finally acquiesced. It is possible that this slight and courteously worded rivalry between the two committees induced earlier action than would otherwise have happened, for two days later — February 10 — Mr. Trumbull, chairman of the Judiciary Committee, reported back a substitute in the following language, differing from the phraseology of both Mr. Sumner and Mr. Henderson:

ARTICLE XIII

SECTION 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

SECT. 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Even after the Committee on the Judiciary by this report had adopted the measure, it was evidently thought to be merely in an experimental or trial stage, for more than six weeks elapsed before the Senate again took it up for action. On the 28th of March, however, Mr. Trumbull formally opened debate upon it in an elaborate speech. The discussion was continued from time to time until April 8. As the Republicans had almost unanimous control of the Senate, their speeches, though able and eloquent, seemed perfunctory and devoted to a foregone conclusion. Those which attracted most attention were the arguments of Reverdy Johnson of Maryland and Mr. Henderson of Missouri, senators representing slave States, advocating the amendment. Senator Sumner, whose pride of erudition amounted almost to vanity, pleaded earnestly for his phrase, All persons are equal before the law, copied from the Constitution of revolutionary France. But Mr. Howard of Michigan, one of the soundest lawyers and clearest thinkers of the Senate, pointed out the inapplicability of the words, and declared it safer to follow the Ordinance of 1787, with its historical associations and its well-adjudicated meaning.

There was, of course, from the first no doubt whatever that the Senate would pass the constitutional amendment, the political classification of that body being thirty-six Republicans, five Conditional Unionists, and nine Democrats. Not only was the whole Republican strength, thirty-six votes, cast in its favor, but two Democrats, Reverdy Johnson of Maryland and James W. Nesmith of Oregon, with a political wisdom far in advance of their party, also voted for it, giving more than the two-thirds required by the Constitution.

When, however, the joint resolution went to the House of Representatives there was such a formidable party strength arrayed against it as to foreshadow its failure. The party classification of the House stood one hundred and two Republicans, seventy-five Democrats, and nine from the border States, leaving but little chance of obtaining the required two-thirds in favor of the measure. Nevertheless, there was sufficient Republican strength to secure its discussion, and when it came up on the 31st of May, the first vote showed seventy-six to fifty-five against rejecting the joint resolution.

We may infer that the conviction of the present hopelessness of the measure greatly shortened the debate upon it. The question occupied the House only on three different days on May 3, when it was taken up, and June 4 to 5. The speeches in opposition all came from Democrats; the speeches in its favor all came from Republicans, except one. From its adoption, the former predicted the direst evils to the Constitution and the Republic; the latter the most beneficial results in the restoration of the country to peace and the fulfillment of the high destiny intended for it by its founders. Upon the final question of its passage, the vote stood: yeas, ninety-three; nays, sixty-five; absent or not voting, 23. Of those voting for the resolution, 87 were Republicans, and four were Democrats. Those voting against it were all Democrats. The resolution, not having secured a two-thirds vote, was thus lost, seeing which Mr. Ashley, Republican, who had the measure in charge, changed his vote so that he might, if occasion arose, move its reconsideration.

The ever-vigilant public opinion of the loyal States, intensified by the burdens and anxieties of the war, took up this far-reaching question of abolishing slavery by constitutional amendment with an interest fully as deep as that manifested by Congress. Before the joint resolution failed in the House of Representatives, the issue had already been transferred to discussion and prospective decision in a new forum.

When on the 7th of June, 1864, the National Republican Convention met in Baltimore, Maryland, the two most vital thoughts that animated its members were the re-nomination of President Lincoln and the success of the constitutional amendment. The first was recognized as a popular decision needing only the formality of republican government, justice, and the national safety demand its Litter and complete extirpation from the soil of the Republic and that while we uphold and maintain the acts and proclamations by which the Government in its own defense has aimed a death blow at this gigantic evil, we are in favor, furthermore, of such an amendment to the Constitution, to be made by the people, in conformity with its provisions, as shall terminate and forever prohibit the existence of slavery within the limits or the jurisdiction of the United States.

We have related elsewhere how, upon this and the other declarations of the platform:

Resolved. That as slavery was the cause and now constitutes the strength of this rebellion, and as it must always and everywhere hostile to the principles of republican government, justice, and the national safety demand its utter and complete extirpation from the soil of the Republic; and that while we uphold and maintain the acts and proclamations by which the Government in its own defense has aimed a death blow at this gigantic evil, we are in favor, furthermore, of such an amendment to the Constitution, to be made by the people, in conformity with its provisions, as shall terminate and forever prohibit the existence of slavery within the limits or the jurisdiction of the United States.

Upon this and other declarations of the platform, the Republican party went to battle. It gained an overwhelming victory a popular majority of 411,281, an electoral majority of 191, and a House of Representatives of 138 Unionists to 35 Democrats. In view of this result, the President was able to take up the question with confidence in his official recommendations. In the annual message which he transmitted to Congress on the 6th of December, 1864, he urged upon the members whose terms were about to expire the propriety of at once carrying into effect the clearly expressed popular will. Said He:

At the last session of Congress, a proposed amendment of the Constitution abolishing slavery throughout the United States passed the Senate but failed, for lack of the requisite two-thirds vote, in the House of Representatives. Although the present is the same Congress and nearly the same members, and without questioning the wisdom or patriotism of those who stood in opposition, I venture to recommend the reconsideration and passage of the measure at the present session. Of course, the abstract question is not changed, but an intervening election shows, almost certainly, that the next Congress will pass the measure if this does not. Hence, there is only a question of time as to when the proposed amendment will go to the States for their action. And, as it is to so go at all events, may we not agree that the sooner, the better? It is not claimed that the election has imposed a duty any further than, as an additional element to be considered, their judgment may be affected by it. It is the voice of the people, now for the first time heard upon the question. In a great national crisis like ours, unanimity of action among those seeking a common end is very desirable — almost indispensable. And yet, no approach to unanimity is attainable unless some deference shall be paid to the will of the majority simply because it is the will of the majority. In this case, the common end is the maintenance of the Union, and among the means to secure that end, such will, through the election, is most clearly declared in favor of such constitutional amendment.

On December 15, Mr. Ashley gave notice that he would, on the 6th of January, 1865, call up the constitutional amendment for reconsideration, and accordingly, on the day appointed, he opened the new debate upon it in an earnest speech. A general discussion followed from time to time, occupying perhaps half the days of the month of January. As at the previous session, the Republicans all favored it, while the Democrats mainly opposed it. However, the important exceptions among the latter showed the immense gains the proposition had made in popular opinion and in congressional willingness to recognize and embody it. The logic of events had become more powerful than party creed or strategy. For 15 years, the Democratic party had stood as sentinel and bulwark to slavery. Yet, despite its alliance and championship, the peculiar institution was being consumed like dry leaves in the fire of war. For a whole decade, it had been defeated in every great contest of congressional debate and legislation. It had withered in popular elections, been paralyzed by confiscation laws, crushed by Executive decrees, and trampled upon by marching Union armies. More notable than all, the agony of dissolution had come upon it in its final stronghold, the constitutions of the slave States. Local public opinion had throttled it in West Virginia, Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Maryland; the same spirit of change was upon Tennessee and even showing itself in Kentucky.

Here was a great revolution of ideas, a mighty sweep of sentiment, which could not be explained away by the stale charge of sectional fanaticism, or by alleging technical irregularities of political procedure. Here was a mighty flood of public opinion, overleaping old barriers and rushing into new channels. The Democratic party did not and could not shut its eyes to the accomplished facts. In my judgment, said Mr. Holman of Indiana, the fate of slavery is sealed. it dies by the rebellious hand of its votaries, untouched by the law. Its fate is determined by the war, by the measures of the war, and by the results of the war. These, sir, must determine it, even if the Constitution were amended. He opposed the amendment, he declared, simply because it was unnecessary.

Though few other Democrats were so frank, all their speeches were weighed down by the same consciousness of a losing fight, a hopeless cause. The Democratic leader of the House, and lately defeated Democratic candidate for Vice-President, Mr. Pendleton, opposed the amendment, as he had done at the previous session, by asserting that three-fourths of the States did not possess constitutional power to pass it, this being if the paradox be excused at the same time the weakest and the strongest argument: weakest because the Constitution in terms contradicted the assertion; strongest, because under the circumstances nothing less than unconstitutionality could justify opposition.

However, while the Democrats as a party thus persisted in a false attitude, more progressive members had the courage to take independent and wiser action. Not only did the four Democrats Moses F. Odell and John A. Griswold of New York, Joseph Baily of Pennsylvania, and Ezra Wheeler of Wisconsin who supported the amendment at the first session again record their votes in its favor, but they were now joined by thirteen others of their party associates, namely: Augustus C. Baldwin, of Michigan; Alexander H. Coifroth and Archibald McAllister, of Pennsylvania; James E. English, of Connecticut; John Ganson, Anson Herrick, Homer A. Nelson, William Radford, and John B. Steele, of New York; Wells A. Hutchins, of Ohio; Austin A. King and James S. Rollins, of Missouri; and George H. Yeaman, of Kentucky; and by their help, the favorable two-thirds vote was secured.

But special credit for the result must not be accorded to these alone. Even more than Northern Democrats must be recognized the courage and progressive liberality of members from the border slave States, one from Delaware, four from Maryland, three from West Virginia, four from Kentucky, and seven from Missouri, whose speeches and votes aided the consummation of the great act; and, finally, something is due to those Democrats, eight in number, who were absent without pairs, and thus, perhaps not altogether by accident, reduced somewhat the two-thirds vote necessary to the passage of the joint resolution.

Mingled with these influences of a public and moral nature, it is not unlikely that others of more selfish interest, operating both for and against the amendment, did not entirely want to do so. One, who was a member of the House, writes:

The measure’s success had been considered very doubtful. It depended upon certain negotiations, the result of which was not fully assured and the particulars of which never reached the public.

So also, one of the President’s secretaries wrote on the 8th of January:

I went to the President this afternoon at the request of Mr. Ashley on a matter connecting itself with the pending amendment of the Constitution. The Camden and Amboy railroad interest promised Mr. Ashley that if he would help postpone the Raritan railroad bill over this session, they would, in return, make the New Jersey Democrats help with the amendment, either by their votes or absence. Charles Sumner, being the Senate champion of the Raritan bill, Ashley went to him to ask him to drop it for this session. Sumner, however, showed reluctance to adopt Mr. Ashley’s suggestion, saying that he hoped the amendment would pass anyhow, etc. Ashley thought he discerned in Sumner’s manner two reasons: (1) That if the House did not adopt the present Senate resolution, the Senate would send them another in which they would most likely adopt Sumner’s own phraseology and thereby gratify his ambition; and (2) that Sumner thinks the defeat of the Camden and Amboy monopoly would establish a principle by legislative enactment which would effectually crush out the last lingering relics of the States rights dogma. Ashley, therefore, desired the President to send for Sumner and urge him to be practical and secure the passage of the amendment in the manner suggested by Mr. Ashley. I stated these points to the President, who replied at once: I can do nothing with Mr. Sumner in these matters. While Mr. Sumner is very cordial with me, he is making his history in an issue with me on this very point. He hopes to succeed in beating the President so as to change this Government from its original form and make it a strong centralized power. Then calling Mr. Ashley into the room, the President said to him, I think I understand Mr. Sumner; and I think he would be all the more resolute in his persistence on the points which Mr. Nicolay has mentioned to me if he supposed I were at all watching his course on this matter.

The issue was decided in the afternoon of the 31st of January, 1865. The scene was one of unusual interest. The galleries were filled to overflowing, and the members watched the proceedings with unconcealed solicitude. Up to noon, said a contemporaneous formal report, the pro-slavery party are said to have been confident of defeating the amendment, and after that time had passed, one of the most earnest advocates of the measure said, This the toss of a copper. (2) There were the usual pleas for postponement and for permission to offer amendments or substitutes, but at four o’clock, the House came to a final vote, and the roll call showed, yeas, 119; nays, – 6; not voting 8. Scattering murmurs of applause had followed the announcement of affirmative votes from several of the Democratic members. This was renewed when, by direction of the Speaker, the clerk called his name, and he voted aye. But when the Speaker finally announced, The constitutional majority of two-thirds having voted in the affirmative, the joint resolution is passed, the announcement so continues the official report printed in the Globe was received by the House and by the spectators with an outburst of enthusiasm. The members on the Republican side of the House instantly sprung to their feet, and, regardless of parliamentary rules, applauded with cheers and clapping of hands. The example was followed by the male spectators in the galleries, which were crowded to excess, who waved their hats and cheered loud and long, while the ladies, hundreds of whom were present, rose in their seats and waved their handkerchiefs, participating in and adding to the general excitement and intense interest of the scene. This lasted for several minutes. In honor of this immortal and sublime event, cried Mr. Ingersoll of Illinois, I move that the House do now adjourn, and against the objection of a Maryland Democrat, the motion was carried by a yea and nay vote. A salute of one hundred guns soon made the occasion the subject of comment and congratulation throughout the city. On the following night, a considerable procession marched with music to the Executive Mansion to carry popular greetings to the President. In response to their calls, President Lincoln appeared at a window and made a brief speech, of which only an abstract report was preserved, but which is nevertheless important as showing the searching analysis of cause and effect which this question had undergone in his mind, the deep interest he felt, and the far-reaching consequences he attached to the measure and its success.

He supposed [he said] the passage through Congress of the constitutional amendment for abolishing slavery throughout the United States was the occasion to which he was indebted for the honor of this call. The occasion was one of congratulations to the country and to the whole world. But there is a task yet before us to go forward and have consummated by the votes of the States that which Congress had so nobly begun yesterday. He had the honor to inform those present that Illinois had to-day already done the work. Maryland was about halfway through, but he felt proud that Illinois was a little ahead. He thought this measure was a very fitting, if not an indispensable, adjunct to the winding up of the great difficulty. He wished the reunion of all the States perfected and so effected as to remove all causes of disturbance in the future, and to attain this end, it was necessary that the original, disturbing cause should, if possible, be rooted out. He thought all would bear him witness that he had never shrunk from doing all that he could to eradicate slavery by issuing an Emancipation Proclamation. But that proclamation falls far short of what the amendment will be when fully consummated. A question might be raised as to whether the proclamation was legally valid. It might be urged that it only aided those that came into our lines and that it was inoperative as to those who did not give themselves up or that it would have no effect upon the children of slaves born hereafter; in fact, it would be urged that it did not meet the evil. But this amendment is a king’s cure-all for all the evils. It winds the whole thing up. He would repeat that it was the fitting, if not the indispensable, adjunct to the consummation of the great game we are playing. He could not but congratulate all present himself, the country, and the whole world upon this great moral victory.

Authors:

J. G. Nicolay

John Hay

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexanderer/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

Sources:

The Century; Volume 38, Issue 6, Oct 1889.

Prologue Magazine, Vol. 25, No. 2, 1993

Also See: