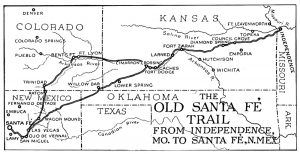

Santa Fe Trail Map

The Beginnings of Legal Trade

Several Americans sought the distinction of being the first to reach Santa Fe, New Mexico, with the intention of trading legally. Although Jacob Fowler and Hugh Glenn were discovered trapping beaver streams north of Santa Fe in 1821, Captain William Becknell is credited with the establishment of the Santa Fe Trail and as the first successful American trader to reach Santa Fe in 1821, thus receiving the title of “father of the Santa Fe Trail.”

Becknell was born in Virginia in about 1787. He first appeared in the Boon’s Lick country of central Missouri in April 1812 when he joined the US Mounted Rangers. By 1815, he had become involved in several business ventures, including the salt trade and a ferry service across the Missouri River. In 1817, he established a residence in Franklin, Missouri. The Panic of 1819 cost Becknell dearly. Unable to repay personal loans he had taken out, Becknell was arrested on May 29, 1821, but was released on a $400 bond. By the summer of 1821, the 34-year-old frontiersman had accumulated a debt of $1,185.42 owed to five creditors and faced the prospect of prison.

On June 25, 1821, before official news of the change in government in Mexico, Captain William Becknell placed an advertisement in the Missouri Intelligencer, looking for men to accompany him on his trading venture westward. The stated purpose of the proposed expedition was the trading of horses and mules, presumably with the Indians, and the catching of wild animals. Members of the expedition were to provide their own equipment and an equal part of the capital for the trade. The men met and elected Becknell to lead their expedition. The August 14, 1821 edition of the Missouri Intelligencer reported that 17 men assembled at Ezekiel Williams’ cabin and set September 1, 1821, for the party to cross the Missouri River at the Arrow Rock ferry. Still contested is whether Becknell anticipated opening the Mexican border to legal trade or whether he was the benefactor of circumstance, having originally intended to trade with American Indians. Becknell would have been aware of the Mexican Declaration of Independence in February 1821 and the Mexican revolt against the Spanish before his departure. Not until September 27, 1821, however, did Mexico legally divorce Spain, yet the Becknell party crossed the Missouri River above Franklin and departed from the natural landmark known as Arrow Rock on September 1, 1821, as planned.

The party crossed the Arkansas River near Walnut Creek, then followed the south side of the river into Colorado, where they followed the Purgatoire River and Chacuaco Creek Southwest, entering New Mexico through Emery Gap. After an uneventful trip, Becknell and company met a troop of soldiers from Santa Fe on November 13. They traveled with the soldiers to San Miguel del Vado and Santa Fe, where Governor Facundo Melgares warmly greeted them. Becknell’s timing was advantageous – he and his trading party arrived in Santa Fe on November 16, 1821. Their trade goods, including calicoes and domestic printed cloth, sold at high prices in the isolated Mexican outpost. Having experienced the profits to be gained by this type of trading venture, Becknell was anxious to return to Franklin and to prepare an even larger volume of goods for his next trip to Santa Fe. To this end, he departed Santa Fe on December 13, 1821. The successful Becknell arrived in Franklin on January 30, 1822, after only 48 days of travel. In only two weeks, William Becknell was the first American trader into Mexican Santa Fe. Soon after Becknell, Thomas James, who viewed Santa Fe as a market for textiles, arrived on December 1. Hugh Glenn and Jacob Fowler, both trappers and American Indian traders from southeast Colorado, departed for Santa Fe on January 2, 1822. Enormous profits were to be gained for the effort expended and the risk taken by traders participating in the Santa Fe trade.

Due to the opening of trade relations between the United States and Mexico and the extreme profits from Becknell’s first successful trade expedition, other expeditions were organized almost immediately, and the Santa Fe trade was initiated. Becknell set off on his second trading mission with 21 men and three wagons, embarking from Franklin, Missouri, on May 22, 1822. Another trading party, led by John Heath, left after Becknell but soon caught up with his entourage, so they traveled together to Santa Fe. Some scholars contend that this expedition signaled the first transportation of goods to Mexico intended for civilian, not American Indian, trade. This was the first American attempt to use wagons in crossing the plains since Becknell’s first trip utilized only pack animals. Using wagons required the party to adopt a trail route that avoided the mountains; this new route partially followed what became the Cimarron Route. Although more strenuous due to water scarcity between the Arkansas and Cimarron Rivers, the Cimarron Route was shorter and much less rugged than the later Mountain Route through Raton Pass. Wagons could easily traverse the new route, where scaling the Mountain Route proved treacherous. On his 1822 journey, Becknell and his party crossed the Arkansas River in Rice County, Kansas, then followed the south side of the river for eight days before heading Southwest into Spanish country. Employing the Cimarron Route also meant the crossing of La Jornada (Spanish term meaning “the journey”), a 60-mile waterless portion of the route where high temperatures usually prevailed. Josiah Gregg, the author of the book Commerce of the Prairies, suggested that Becknell’s second expedition was closest to failure on this portion of the Santa Fe Trail; Gregg’s father, Harmon, was a member of Becknell’s expedition. By late July 1822, Becknell was in San Miguel, New Mexico. After continuing to Santa Fe, he returned to Franklin, Missouri, in October 1822. Becknell’s second trading party brought $3000 worth of trade goods to Santa Fe, and the party enjoyed the rewards of a 2000 percent profit on their investment. The demand for American and European goods was emphasized by Becknell and others selling even their wagons, worth $150, for $700. The profits derived by Becknell from this trip went a long way toward pacifying his creditors back in Franklin.

Several other trading parties were assembled quickly to trade with the Mexicans. Colonel Benjamin Cooper and 15 men left Franklin, Missouri, with a trading party in early May 1822. Like Becknell, Cooper took the Cimarron Route, encountering hard times when they reached La Jornada. The problem arose when the trading party expended its water supply. They were forced to kill their dogs and cut the ears of their mules to have hot blood to drink to survive under extreme weather conditions. On the verge of abandoning the expedition, they chanced upon and killed a buffalo. They utilized the stomach water from this animal to quench their thirst and subsequently found water in the vicinity, as had the buffalo. This trail incident was once believed to have happened to Becknell’s party, but it is now believed to have actually happened to the Benjamin Cooper party in 1823. Cooper’s party was forced to return to Franklin one night after their horses strayed from camp. Even then, the handful of men that were sent out after the horses were robbed of their guns, clothes, and six of their horses by Osage Indians. James Baird and Samuel Chambers, imprisoned ten years earlier for illegal trading, also led an expedition to Santa Fe in the autumn of 1822. The Baird-Chambers trading expedition experienced a severe snowstorm, which forced them to spend the winter in camp near the Arkansas River. When spring came, the traders could not transport their goods since most of their draught animals had perished in the winter cold. The traders cached their commodities on the north bank of the Arkansas River and went to Taos, New Mexico, where they purchased mules and returned for their merchandise. The place where the traders hid their goods became known as “The Caches” and was an important mile marker and campsite for future travelers.

After 1821, the Santa Fe trade supplied much-needed manufactured goods and provided economic success for New Mexican merchants and those who supplied goods traded to US markets. While much of the wealth from the trade augmented established rich traders, others profited by supplying products and freighting along the trail. As the wealthy class in New Mexico, the wealthy controlled the trade of their goods and benefited greatly from the amount of merchandise that American traders shipped into their markets. They also separated themselves from and maintained economic control over the “commoners” and the poor. Augustus Storrs, a native of New Hampshire and Franklin, Missouri postmaster who traveled to Santa Fe in 1824 as part of the first trade caravan, described the conditions prevailing in Santa Fe upon his arrival:

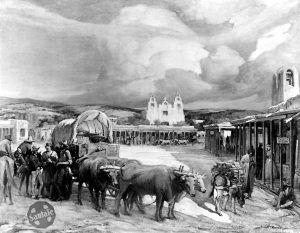

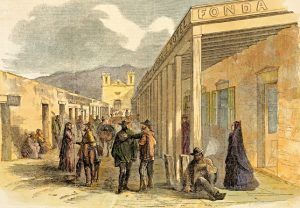

“Although necessity has limited their artificial wants, they have not, within themselves, all the necessaries and conveniences of life. Iron is difficult to obtain and sells at $100 per cwt., although the country abounds in ore. Woolen goods are scarce and dear, yet the Internal Provinces produce twice the wool necessary to clothe their inhabitants. All plates, dishes, bowls, water vessels, and every description of castings are supplied by a substitute manufactured from clay by the civilized Indians. This ware is superior of its kind and is the invention of the aborigines. They are almost entirely destitute of artisan’s tools of every description, and their agriculture implements, such as carts, plows, harrows, yokes, spades, etc., are universally destitute of the least advantage of iron-work. Their spinning uses a wooden spindle operated by a twirl of the thumb and finger. These particulars are, in themselves, too trifling for enumeration. Still, when considered in relation to the government’s late administration, the people’s condition, and the practical consequences to be deduced by statesmen, they become more important. From them, also, may be inferred the variety and extent of supplies demanded by that market. It will be remembered that I speak of New Mexico only, to which my observation was limited. The report speaks more favorably of the condition of the other Internal Provinces. Santa Fe was established in 1610 in a narrow valley unoccupied by American Indians. The city was irregularly laid out except for the public square, while the immediate environs consisted of farms.”

Farming on these arid lands was possible due to irrigation systems from the Santa Fe River. The majority of the residents of Santa Fe were poor, but a very wealthy minority also resided there. The church was the center of cultural life in the town, and the educational system was poorly developed. By 1821, approximately 5,000 people lived in Santa Fe. For the next 25 years, this town grew into the major western terminus for international trade along the Santa Fe Trail.

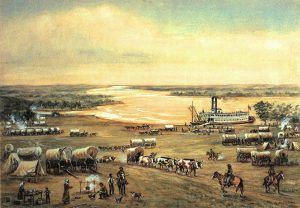

As trade with Mexico became more popular, numerous caravans were organized yearly. The first caravan to Santa Fe left Mount Vernon, Lafayette County, Missouri, on May 25, 1824. This particular caravan consisted of 81 men, 156 horses and mules, 23 four-wheeled carts, one piece of field artillery, and $35,000 worth of goods for trade; it was guided by Augustus LeGrand, a former resident of Santa Fe; Meredith M. Marmaduke, later governor of Missouri; Augustus Storrs, the Franklin postmaster; and William Becknell. Having reached Santa Fe, a few traders continued to the Mexican states of Chihuahua and Sonora; others chose to return to Missouri, arriving there on September 24, 1824. Becknell’s connection with the Santa Fe Trail lasted until 1826 when he completed another trip to Santa Fe (August 1824-June 1825). He also aided the Sibley Survey by running mail to and from the survey party, delivering wagonloads of supplies, and occasionally acting as a guide.

Another individual who played a significant role in the early years of the Santa Fe trade was US Senator Thomas Hart Benton from Missouri. Benton ardently advocated opening trade with Mexico across the plains in his younger days as editor of the St. Louis Inquirer. As a senator, after Missouri became a state and the Mexican frontier was opened to trade in 1821, “he pushed the project with renewed enthusiasm.” Senator Benton was a staunch advocate for the Santa Fe trade, encouraging it through his writings and aiding it through his efforts in Congress. He saw trade as an economic stimulus for his state and a solution to financial instability caused by quantities of worthless paper currency and a shortage of hard currency. Benton’s Missouri constituents had two significant concerns. Firstly, dangers posed by Indians along both primary trail routes were a real and frequent possibility.

The Mountain Route was more difficult to traverse due to its mountainous terrain that led wagon trains through Cheyenne, Arapaho, Ute, Kiowa, Comanche, and Jicarilla Apache territories. The Cimarron Route’s terrain, though much less rugged, still posed the danger of much less water and a higher threat of attacks by nearby tribes such as the Comanche and Apache. Passing through Indian territory often led to attacks on wagon trains by the occupying tribes. Secondly, the customs regulations imposed on the trade by Mexican authorities alarmed traders. After being questioned by Senator Benton, traders returning from Santa Fe to Missouri in 1824 sent their complaints and requests to Washington. In 1825, Senator Benton drew the attention of the US Congress to the growing commerce between the frontier towns of Missouri and the Mexican city of Santa Fe. As evidence, he provided a statement from Augustus Storrs, who had traveled to Santa Fe in 1824 as part of the first trade caravan. In answer to Senator Benton’s questions, Storrs explained that the residents of Santa Fe and the other Pueblos of Mexico’s northern provinces greeted the traders from Missouri with open arms. He listed the types of goods transported to Santa Fe as cotton goods, including bolts of cloth and shirting, handkerchiefs, cotton hose, woolen goods, silk shawls, cutlery items, mirrors, and other items. In exchange, traders returned to Missouri with Spanish-milled dollars, gold, and silver in bullion, beaver furs, and mules. Storrs’s testimony also explained that the American traders paid a duty of “25 percent. ad valorem” to the Internal Provinces of Mexico government on goods brought into the country. Storrs indicated that rumors of impending raises in the duty were prevalent:

“The certain object of this increase is to place their commerce, from the south [e.g., Mexico City and Chihuahua along the Camino Real], on an equal footing with that of the Americans, and the measure, I have no doubt, is strongly urged by a few, who have, heretofore, monopolized the sales and fixed the prices of the country.”

Storrs believed that US agents stationed in Santa Fe and Chihuahua could protect traders from the greed and unpredictability of New Mexican officials. Augustus Storrs himself was appointed US consul in Santa Fe in 1825. The traders thought the duty had been arbitrarily imposed by the governor of New Mexico and not legally by the Mexican government. However, the Mexican government also imposed arbitrary and oppressive taxes and regulations on the Santa Fe trade. Santa Fe, Taos, and San Miguel del Vado each had a customs house, though Santa Fe remained the true port of entry. Although manifests and records were kept of the goods passing through these customs houses and the taxes levied and paid, graft and corruption were major problems. A minimal revenue, which should have been paid to the government, actually found its way into the Mexican treasury.

The Sibley Survey, 1825-1827

Missouri traders like Augustus Storrs requested that the US government survey and mark a permanent road over which Santa Fe trade could be conducted. They additionally requested military protection from future threats, such as Indian interference, to what Missourians believed would be a continuously expanding trade route. The Missouri legislature supported the traders’ cause, as did Missouri senators Thomas Hart Benton and David Barton. Benton forcefully guided a bill through Congress, calling for a survey of the trail from Missouri to the international border along the north bank of the Arkansas River. The result of these efforts was the passage of a bill on March 3, 1825, providing for the survey of a “highway between nations” and for treaties to be made with the Indians through whose lands the road passed.

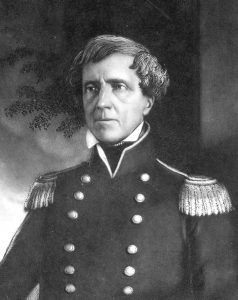

The survey began in July of 1825 and became known as the “Sibley Survey,” after George Champlin Sibley, who led the survey team, which included Benjamin H. Reeves and Thomas Mather. The Santa Fe Trail Survey Expedition embarked from Fort Osage in present-day Sibley, Missouri, on the Missouri River. The expedition surveyed and marked the trail between Missouri and Santa Fe, and the surveyors kept extensive notes and records. Rather than survey the route then used by traders, the Sibley Expedition followed and marked – by erecting earth mounds – a somewhat different route. Some historians suggest that the Sibley Survey never fulfilled its purpose. This was partly because the survey ended in Taos, New Mexico, with a branch road to Santa Fe from Taos surveyed later. Upon completing the survey in 1827, the surveyors’ records were sent to Washington, D.C. Unfortunately for traders and travelers of the Santa Fe Trail, little of the valuable data was published or made public knowledge. Within a few years, the earth mounds had disappeared, leaving only wagon ruts to mark the trail to Santa Fe. Sibley thought the survey was unnecessary because he agreed with the wagon men that they knew the route to Santa Fe, even without man-made markers. Indeed, Sibley later echoed the contention by some individuals that the traders themselves had already performed the task of marking the Santa Fe Trail. He stated in his journal, “The road as traveled is already well enough marked by the wagons; the buffalo and Indians would soon throw down any mounds put up.” The Sibley Survey had little effect on the development of the trade or the trail; however, it did provide national publicity.

As provided in the 1825 bill authorizing the survey and marking of the road to Santa Fe, treaty negotiations were undertaken with the Osage and Kanza tribes. Two treaties – one with the Great and Little Osage on August 10, 1825, and one with the Kanza on August 16, 1825 – were identical except for the preliminary and concluding paragraphs specifying the tribe. The first four articles provided that “in consideration of the friendly relations existing” between the two Indian Nations and the US, the Indians would allow the road to be surveyed and marked, agree that the road would be “forever free for the use of the citizens of the United States and the Mexican Republic… without hindrance or molestation”; “render…friendly aid and assistance” to traders when it was within their power; agree that the “road aforesaid shall be considered as extending to a reasonable distance on either side, so that travelers thereon may, at any time, leave the marked track, to find subsistence and proper camping places.” The fifth article required that each tribe receive $500 in money and merchandise from the United States government in payment for the considerations enumerated.

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs, William Clark, Benjamin H. Reeves, George C. Sibley, and Thomas Mather, conducted the negotiations. The meetings between the Osage Indians and the US commissioners took place at Council Grove, a rendezvous campsite on the Neosho River in what is now Morris County, Kansas; the treaty with the Kanza was signed at Sora Creek (Dry Turkey Creek), Southwest of present-day McPherson, Kansas. The treaties were signed by Reeves, Sibley, Mather, and 16 members of the Osage and Kanza tribes, including seven Osage chiefs and four Kanza chiefs. Tariffs and Taxes Issues with fair trade, Mexican tariffs, and duties continued during the first two decades of the Santa Fe trade. Despite the enormous profits to be made on American goods sold at Santa Fe, the traders had to surrender some of their profits to the Mexican authorities in the form of customs duty. Customs duty on dry goods was officially 25 percent; in actual practice, however, this often varied from 10 to 150 percent. The duty was based on the arbitrary value placed on the goods by the Mexican officials at the customs house. Corruption was rampant, and during the early years, Mexican officials received as much as a third of the duty for their personal use in addition to any bribes that changed hands. During the 1830s, while serving as the customs collector at Santa Fe, Manuel Armijo experienced difficulties keeping up with the ever-changing Mexican tariff schedules. Various duties and taxes existed then, including national import duties, state excise taxes, taxes on animals and wagons, taxes on establishing a retail shop, and taxes on required documentation. Each port of entry also seemed to employ its own tariff schedule. Recognizing these difficulties, Armijo shifted from ad valorem duties to a flat $500 impost on every wagon. Santa Fe traders, in response, started using larger wagons pulled by ten or 12 mules or reloading goods into fewer wagons outside Santa Fe, leaving the empty wagons until their return trip. As a result, Armijo removed the per wagon tax in 1839.

American traders regularly argued that the Mexican trade duties resulted in them being taxed twice on the same merchandise, once when it was imported from Europe and again when it was taken into Mexico. To place American traders on equal footing with Mexican competitors who were imported directly from Europe, one Missouri merchant proposed that the U.S. should create a rebate or debenture of American duties for Santa Fe traders who were being impacted by this double taxation. Between 1831 and 1845, American traders appealed to Congress for help. It was argued that this would improve American traders’ ability to reach markets farther south in Mexico and increase the value of the Santa Fe trade. In 1842, the acting US consul in Santa Fe sided with the traders. Congress, however, refused to act at that time.

American traders were also worried about the increasing influence of Mexican merchants and were concerned that these businessmen threatened their business interests. During the 1830s, a merchant class began to emerge in Santa Fe, consolidating capital, beginning to control markets, trading in the US, and dealing directly with wholesalers. By the late 1830s, Mexican traders had gained dominance over the trade and were transporting the bulk of the goods bound for Santa Fe. They were involved in all aspects of the trade in Santa Fe, as well as in Missouri, the eastern US, Mexico, and California. Many wealthy Hispanic merchants established their own contacts with wholesalers and merchants in the eastern US, bypassing American merchants and businessmen in Missouri. However, on March 3, 1845, the US Congress passed the Drawback Act. The law allowed traders to be reimbursed for all but 2.5 percent of the US duties of foreign merchandise if advance notice of intent to re-export the goods to Mexico was given and provided that they were shipped to Mexico in original packages with certified invoices by way of Independence, Missouri or either Van Buren or Fulton, Arkansas. In addition, the goods were subject to inspection by American customs agents, and traders were required to provide a bond of three times the US duties. Trade increased dramatically in the year after the passage of this legislation, increasing the value of goods transported over the trail to Mexico.

Traded Goods

During his 1825-1827 survey expedition, George C. Sibley sent a letter to his associates in Missouri outlining the items he felt would sell best in Santa Fe. His enumeration provides information on the types of items leaving Missouri for Santa Fe in the early years of the trade. Cloth, food, medicine, and hardware figured prominently in Sibley’s list. In the 1830s, according to Santa Fe trader Alphonso Wetmore and US Secretary of War Lewis Cass, the principal goods being traded from Mexico back to Missouri included Mexican dollars, fine gold, beaver pelts, horses, mules, and asses. Manifests listed the items passing through the Mexican customs house in Santa Fe to assess the amount of tax due. Two documents from 1835 provide evidence that the types of items traded in this period were not significantly different than those of the preceding years. The quantity and diversity of merchandise shipped into Santa Fe changed dramatically between the 1820s and the 1840s; the price of similar items during this period also declined.

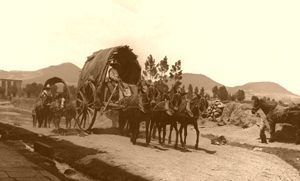

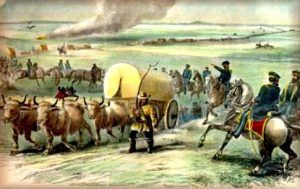

Supplies headed for Santa Fe, courtesy of the Kansas Historical Society

The types of goods transported from the United States and Europe to be sold at Santa Fe reflect the international character of the trade. Cloth, including cotton, silks, and linens, was the most important item of merchandise transported to Mexico. Other items sold in Santa Fe included dry goods, hardware, tableware, cutlery, jewelry, whiskey, champagne, and other manufactured goods. Traders acquired gold and silver Mexican dollars, silver bullion, gold dust, mules, donkeys, and furs in Santa Fe for their return trip to the United States. Mexican merchants also found a market in Missouri for mules, asses, buffalo robes, furs, and small volumes of coarse wool. Trappers played a significant role in the Santa Fe trade by providing trail merchants with manpower for their caravans, customers for their merchandise, and sources of supply for one of their most popular commodities — fur.

The estimated total value of annual goods traded along the Santa Fe Trail between 1821 and 1846 increased dramatically, although it was not steady. Some of the fluctuations in the expanding trade can be attributed to conditions along the trail, while others were related to issues and events in the US or Mexico: for example, confrontations between traders and Indians along the trail, particularly in late 1828 and early 1829; the Panic of 1837; or the Texas uprising in 1841 to 1843.

The Santa Fe trade affected the industrial areas of the eastern United States, especially the Northeast, providing a new market for large quantities of merchandise. American and European goods were traded extensively, encouraging New Mexican material dependency upon Anglo-American trade items and the industrial development of the northeastern US. The primary wholesale sources of goods that the traders hauled to Santa Fe were several prominent firms in New York City, Boston, Philadelphia, and St. Louis. In the early trade period, goods were purchased by independent traders or by an intermediary for a group of traders directly from these cities. Many Missouri merchants purchased large quantities of goods on yearly trips east and advertised them for sale specifically as “Santa Fe Goods.” By the 1840s, forwarding and commission houses acted as middlemen between the eastern wholesalers and the Santa Fe merchants, with Kansas City as the staging point for their caravans.

Travel on the Trail

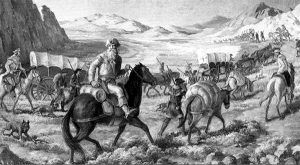

Just as during the early years of trade between Missouri and Mexico, merchants engaged in the Santa Fe trade learned what merchandise would bring the most significant profits and which eastern wholesalers offered the best deals. Santa Fe Trail traders and travelers determined the best travel routes for freighting goods, whether with pack animals or wagon caravans. They found the best places to cross rivers and streams or modified stream banks to make crossings faster and safer. They determined the best locations to camp, the best streams and springs that had constant potable water, and all the things that travelers across the Plains in the early to mid-nineteenth century needed to know to complete their journeys successfully. They also found what dangers were most likely encountered and where to expect problems. They figured out the best means of travel, the items needed for the journey, and how to organize a wagon train for long-distance freighting. However, traders also made changes as necessary to maintain trade, increase their profits, travel safely, or take advantage of changing conditions. The Missouri River was navigable between March and November in central Missouri. Towns with river landings provided potential jumping-off points for the Santa Fe Trail, as merchandise for the trade could be brought in by riverboat at lower rates than those offered by overland routes. The river town of Franklin in central Missouri served as the departure point for William Becknell and other early traders. After a Missouri River flood inundated Franklin in 1828, New Franklin was established two miles northeast of the flooded town of Franklin. Still, he did not play a significant role in the trade, as by 1828, the terminus had moved slightly west. The ferry at Arrow Rock – a bluff along the west bank of the Missouri River – became widely used during the early years of the Santa Fe Trail, especially as Mexican merchants made their way to Franklin. As steamboats came into everyday use, ports were established upstream and were found to offer advantages.

These steamboat landings were established near the big bend in the Missouri River in Jackson County, Missouri. With the establishment of Fort Leavenworth in Kansas Territory in May 1827, a new steamboat landing was available for military freight, which could then be transported along the Santa Fe Trail via military roads, linking the post to the trail. By freighting goods on the river to these upstream landings, traders saved nearly 100 miles of difficult travel over unimproved and often muddy roads. During the 1830s and 1840s, Independence and Westport, and later, Kansas City, were the principal outfitting locations and trailheads at the eastern end of the Santa Fe Trail. By the mid-1840s, trail traffic in Westport had caught up with or exceeded the trail traffic in Independence. At least three different trail routes developed in the greater Kansas City area depending upon which river landing and outfitting town a caravan started and which crossing was used over the Big Blue River.

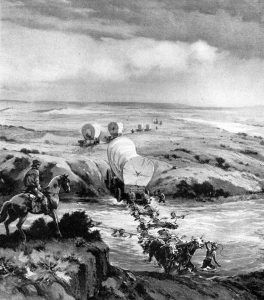

During the first 25 years of the Santa Fe Trail, the Cimarron Route was used almost exclusively over the Mountain Route, which was not considered a viable route for wagon traffic due to its geography. Wagons more easily traversed the relatively level terrain of southwest Kansas than the steep slopes of the Mountain Route into New Mexico. The Mountain Route was rarely used in the years preceding the Mexican-American War except by pack animals.

No improved amenities were found along the trail in the early years. Campsites were carefully selected and needed to provide at least water, grass, and fuel. Draught animals could survive a night without plentiful grass, but neither humans nor animals could survive long without water. Most camping areas were located adjacent to streams or springs. Travelers encountered numerous rivers and streams along the trail. Some were crossed with little trouble, but others with steep banks or muddy bottoms were more difficult to manage and posed significant obstacles for travelers. In 1844, author and traveler Josiah Gregg described crossing the Little Arkansas River:

“Although endowed with an imposing name, it is only a small creek with a current but five or six yards wide. But, though small, its steep banks and miry bed annoyed us exceedingly in crossing. It is the practice upon the prairies on all such occasions for several men to go in advance with axes, spades, and hatchets and, by digging the banks and erecting temporary bridges, to have all ready by the time the wagons arrived. A bridge over a quagmire is made in a few minutes by cross-laying it with the brush (willows are best, but even long grass is often employed as a substitute) and covering it with earth, across which a hundred wagons will often pass safely.”

Crossings became more dangerous after heavy rains when streams were in flood stage. Sometimes, waters remained high for several days, causing significant delays. Even when water levels were lower, crossing streams often caused large caravan bottlenecks as wagons had to wait their turn. Some crossings wore out men and livestock working to move wagons bogged down in mud, and quicksand was a danger that could be encountered on some streams, particularly the Arkansas River. Most of the troublesome crossings were encountered in Kansas.

Many other dangers lurked along the trail. Storms with high winds, heavy rains, and hail caused damage to wagons, drove off livestock, and resulted in injuries. Winter storms with heavy snow and frigid temperatures bogged down wagons and killed livestock and travelers. At least two caravans suffered from winter storms. In the winter of 1822-1823, the Baird-Chambers trade caravan, as noted above, was caught in a blizzard on an island in the Arkansas River west of modern-day Dodge City. They were forced to cache their merchandise and continue to “Touse” [Taos]. They came back in better weather and retrieved their cached goods. In 1841, Don Manuel Alvarez and his small trading party were caught in a blizzard at Cottonwood Creek Crossing. Two men and most of the company’s mules were frozen to death. Livestock stampedes, particularly of oxen, were common because, as Josiah Gregg noted, they tended to be “exceedingly whimsical creatures when surrounded by unfamiliar objects. One will sometimes take a fright at the jingle of his yoke-irons or the cough of his mate and, by a sudden, flounce, set the whole herd in a flurry.”

Injuries were also possible from guns and knives handled by the traders and travelers for hunting and protection, though sometimes used in fights against fellow travelers. Rattlesnakes, bees, poison ivy, nettles and briars, and other native fauna and flora could also pose dangers. Because of incidents like the Baird-Chambers expedition, travelers learned which seasons of the year were best suited for travel. During the winter, Missouri traders purchased goods in the East and brought them to the trailheads in Independence or Kansas City to be ready for departure in early May.

Leaving in May would ensure adequate grazing for the mules and oxen on the prairie. Eastbound caravans usually left Santa Fe on September 1, arriving in Missouri around October 10. Caravans could accomplish between ten and 18 miles a day and, barring significant delays could reach their destinations within a month and a half. Delays due to rain were common, especially near the eastern part of the trail, as the caravans often had to wait for the water to recede from streams to cross.

Various travelers recorded their journeys and provided lists of places along the trail and approximate mileages between them. In later years, guidebooks were published for travelers, providing itineraries and tables of distances between campsites. Differences appear in the various listings of trail campsites, even between those recorded only a year or two apart. Some of these differences were due to names of places changing or to increased knowledge over time, while others were due to actual changes in the route of travel. The mileage given on early itineraries was often inaccurate, but accuracy improved in later years with better measurement methods. Both similarities and differences can be seen in these lists of significant stops and distances along the trail between Independence, Missouri, and Santa Fe, New Mexico. One of the individuals who wrote an itinerary was trader Alphonso Wetmore. In 1828, he maintained a diary while serving as the captain of a Santa Fe-bound caravan that encountered heavy rains and swollen streams. In addition to his Santa Fe Trail writings, he wrote prolifically about life in the Army and Missouri. Wetmore’s Santa Fe Trail itinerary, published in 1837 in his Gazetteer of the State of Missouri, lists 67 significant places along the Cimarron Route, including stream crossings, springs, water holes, and campgrounds. He estimated the total distance between Independence and Santa Fe as 897 miles.

Josiah Gregg’s total mileage differed from Wetmore’s. In his 1844 Commerce of the Prairies, Gregg provided a table listing prominent places and distances along the Cimarron Route based on his six trips along the Santa Fe Trail. He estimated the distance between Independence and Santa Fe along this route as 770 miles and showed 37 major named places. The most notable difference between the Wetmore and Gregg itineraries is the estimate of the total aggregate mileage between the same starting and ending points. Distances between listed places on Wetmore’s and Gregg’s itineraries varied from two to 40 miles. During the early years of the Santa Fe Trail, traders and travelers settled on a basic route (the Cimarron Route) between Missouri and Santa Fe, as well as learned and established some basic rules of the road. These included which transportation methods were best suited along the route, the best ways to efficiently organize trade caravans across the Plains, how to protect the cargo and livestock during times of danger, and choosing the most important items that were needed by the traders along the route. William Becknell used horses as pack animals on his first trade trip; Mexican traders used burros and mules, and arrieros (muleteers) were familiar with their use traveling the rugged Camino Real. No mention of mules in Missouri has been identified before 1824; apparently, the first mules came to the state over the Santa Fe Trail. Goods carried on pack animals had to be loaded each morning and unloaded each evening, a time-consuming process even for experienced arrieros. Pack animals had some advantages over wagon travel in that they were better suited to rough terrain and could negotiate steep stream banks. Wagons offered the added benefit of just one loading, unlike the packing and unpacking required when using pack animals.

Wagons were first used over the Santa Fe Trail in 1822 when William Becknell used three wagons on his second trading expedition. Josiah Gregg, by contrast, identifies 1824 as the initial year for wagon transport across the trail; however, he credits a company of 80 traders with introducing this type of animal-drawn vehicle. His account relates 25 wheeled wagons – two carts, one or two road wagons, and the remainder of Dearborn carriages – carrying $25,000 to $30,000 worth of merchandise. Once it was proven that wagons could journey via the Cimarron Route, wagons became the standard means of transportation, though some travelers continued to use pack mules until 1826. Mules and burros were more frequently used to carry loads back to Missouri than from Missouri to Santa Fe, as it was profitable for traders to sell their wagons in Santa Fe. For instance, William Becknell sold a wagon in New Mexico for $700; he had paid $150 for it in Missouri.

The wagons initially used by the traders consisted of various types and sizes, exemplifying the range of wagons available to traders. Early accounts of wagons used on the trail included road wagons, “light running wagons,” carts, and Dearborn carriages, though the actual descriptions of these vehicles are unclear. As the volume of trade increased, and with the imposition of Mexican taxes of a set amount per wagonload regardless of size, more consistency in wagons became apparent by the 1830s. Larger capacity wagons resulted, with typical cargoes of more than 5000 pounds, requiring 10 or 12 mule hitches.

The wagons most widely used over the trail were manufactured in Pittsburgh and were used by American and Hispanic traders alike. A heavy type of wagon, known as the “Murphy Wagon,” was commonly used to transport goods. These wagons were named after Joseph Murphy, a St. Louis wagon maker, and had larger wheels and other dimensions than the typical Santa Fe freight wagon. The typical Santa Fe wagon was described in the June 30, 1860, Westport Border Star. According to the Star, the “diameter of the larger wheel is five feet two inches, and the tire weighs 105 pounds. The reach is eleven feet, and the bed 46 inches deep, 12 feet long on the bottom and fifteen feet on the top, and will carry 6,500 pounds across the plains and through the mountain passes.” Drawn by a yoke of six oxen or a team of six mules, these wagons could accomplish between 12 to 15 miles per day when heavily laden and up to 20 miles per day when empty. The number of wagons composing a caravan varied from 26 in 1824 to 230 by 1843 to 400 in some instances.

Though horses were used for the first few years of the trade, mules and oxen became the principal draught animals. Early Santa Fe traders were reluctant to use oxen, so mules were initially used to draw trail wagons. However, in 1829, Colonel Bennet Riley hitched oxen to military supply wagons taken on the first military escort for traders traveling the trail. Each wagon utilized six or eight animals, but when pulling heavier loads, especially on the outbound journey, up to 12 animals may have been employed. Oxen could pull heavier loads than mules and were cheaper; however, they did not tolerate hot weather well, and their tender feet and poor performance on the short, dry prairie meant that mules were a better investment despite their higher initial cost. To overcome the tenderness of their feet, oxen were shod with iron shoes or, occasionally, moccasins made of raw buffalo skin. Even though mules were prone to acquiring very smooth hoofs, they did not require shoeing, though some were shooed anyway. Extra animals often followed the wagon train, providing fresh oxen or mules at points along the trail.

Trail Travelers and Traders

Proceeds obtained from the early expeditions enticed growing numbers of traders to pursue the trail to and from Santa Fe, though the motivation prompting travel varied from individual to individual. The Santa Fe Trail attracted travelers with diverse backgrounds, interests, and purposes – explorers, trappers, traders, fortune hunters, gold seekers, soldiers, health seekers searching for the “prairie cure,” tourists, journalists, and settlers. Taking part in the lucrative trade between Missouri and Santa Fe was the primary reason that most travelers followed the trail before the war with Mexico. Even before legal trade between Mexico and the United States commenced, it had been apparent that there was a demand in the Southwest for goods from the eastern seaboard. With the legalization of trade, demand increased, and increasing numbers of traders sought to satisfy that demand in return for considerable profits. Many people who traveled over the trail were traders who used this highway of commerce to conduct their business and maintain their occupation. Others who traveled the trail during this period were employees of traders, military servicemen, trappers, Indian traders, or immigrants in search of opportunities elsewhere.

In the early years, most traders were men with limited capital to put into the trade, and they preferred to conduct their business personally or through a trusted intermediary. Many previously had been involved in the fur trade or trade with Indians and were familiar with Fort Osage and the country between Missouri and Santa Fe. Some were small businessmen, primarily from Missouri, although records indicate that Tennessee, Kentucky, and Alabama were among other states also represented. A few were farmers with extra capital to invest or capital raised from mortgaged farms and a desire for adventure. Ewing Young, a Missouri farmer and trapper, sold his farm in 1822 to finance his trading venture to Santa Fe with Becknell’s caravan. In this, Mr. Young was not alone. Other farmers who had suffered in the Panic of 1819 mortgaged their lands to raise the necessary capital to “get in on” the profits of the Santa Fe trade.

Santa Fe traders were typical of the mercantile capitalists of the Commercial Revolution. In contrast to industrial capitalists who flourished in more developed metropolitan areas, mercantile capitalists flourished in less developed regions where they were able to “acquire scarce monetary exchange acceptable for the purchase of foreign goods,” create and become the lending system instead of “the absence of an efficient system of indirect lending of capital,” and effectively haul “purchases over vast stretches of water or sparsely settled land.” Items, both wholesale and retail, were traded in response to the changing demands of consumers and shifting markets. As a result, the Santa Fe trader had to be flexible in his approach to trade. Gregg, The Santa Fe trader, usually operated alone, and he furnished or made arrangements to lease his own mode of transportation since no national or international transportation network existed. The Santa Fe trader often did not receive money in return for his merchandise, so it was necessary to extend credit or employ some form of exchange to conduct business. Since the trader crossed state and national boundaries, he needed to seek cooperative relationships with state and national governments. John, James, and Robert Aull were well-known early Santa Fe traders who subscribed to the viewpoint of the mercantile capitalist. As such, their backgrounds and activities were exemplary of other early traders.

John Aull arrived in Chariton, Missouri, from Delaware around 1819. He operated a store there with two other partners until 1822, when he moved to Lexington, Missouri, and ran a general store until he died in 1842. His younger brothers, James and Robert, went west in 1825. James Aull started his store in Lexington on his arrival and opened branches at Independence in 1827 and Richmond, Missouri, in 1830. Robert Aull started a store in Liberty, Missouri, in 1829. In 1831, James and Robert Aull combined forces to manage a family firm, which operated all four stores until their partnership was dissolved in 1836. During this partnership, James managed the Lexington store; Robert was responsible for overseeing the one at Liberty, and Samuel Owens was given responsibility for the one at Independence.

The variety of merchandise available at the Aull stores reflected the demand for goods from Santa Fe traders and consumers farther west. Dry goods from the Atlantic seaboard; hardware from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; flour from Cincinnati, Ohio; groceries from New Orleans, Louisiana; leghorn bonnets, books, and medicines were among the diversity of items found in these stores. James Aull often selected many of these items on annual winter trips to Philadelphia, New York City, and points in between. He would leave Lexington in January and travel by horseback or wagon to St. Louis by way of Fayette, Missouri; then by stagecoach to Louisville, Kentucky, by way of Vincennes, Indiana; then on to Pittsburgh and, finally, by overland stage to Philadelphia and other eastern destinations. Every winter, James Aull traveled east to order merchandise for the stores from wholesalers, especially Aull’s eastern representative, Siter Price and Company, in Philadelphia. Most goods were shipped by steamer to New Orleans, then up the Mississippi River to St. Louis, then up the Missouri River. Like other traders, the Aulls bore the expense of transporting the goods to Missouri. Combining orders with other traders could reduce the shipping charges from eastern wholesalers. The transportation cost between Missouri and either Santa Fe or Chihuahua was much less, but the traders also covered it. James Aull purchased $35,000 worth of merchandise on one of these annual trips east in 1831, while one year later, he secured another $45,000 worth of items to serve the expanding western markets for such goods. Since many eastern trading firms extended 12 months’ credit to merchants, the Aulls extended six to 12 months’ credit to local customers who were involved in agriculture. Sometimes, the Aulls needed to get a credit extension from their eastern suppliers due to delays caused by late mail delivery, changing currency, low water levels in rivers, steamboat disasters, and the inability of their customers to repay them for merchandise purchased. Between 1831 and 1836, the Aulls took the lead in building and owning three steamboats, constructing a ropewalk to produce rope from local hemp, and operating a saw and gristmill. James Aull anticipated the Panic of 1837, and despite being able to recover only $500 of the $25,000 owed to his Independence store, the Aulls were able to stay in business on a smaller scale until the economic situation improved.

The Aulls also attempted to cultivate a symbiotic relationship with state and national governments for trade. To this end, during the Mexican-American War, James Aull and Samuel Owens found themselves part of a “TradersBattalion” consisting of two military companies mustered by Colonel A. W. Doniphan, commander of a regiment of Missouri volunteers. Mexicans killed Samuel Owens at the Battle of Sacramento, while James Aull was stabbed to death on June 23, 1847, by four Mexicans intent on robbing the new outlet store he had just established in Chihuahua. The characteristics of the trail’s travelers changed during the trade. The dangers of trail life and the sense of adventure provoked by accounts of cultural confrontations encouraged some Americans to engage in travel or trade on the Santa Fe Trail.

Many Americans were insatiably curious about the vast, unknown western lands and what they viewed as the strange and exotic customs of the Mexican and Indian inhabitants. Some were encouraged to travel west by the opportunity to explore these areas and reap the supposed health benefits. Stories of these adventures were available in newspapers and, after the 1850s, in popular magazines such as Leslie’s Illustrated and Harper’s Weekly, or dime novels. However, many individuals did not consider early Santa Fe Trail traffic pleasurable. As Santa Fe Trail traveler Marion Sloan Russell echoed in her published memoirs, “The romance came later…largely in retrospect.” The possibility of improved health impeded some from traversing the trail. George Frederick Ruxton, an English sportsman, noted the health benefits of a trip across the Santa Fe Trail when he wrote the following in 1861:

“It is an extraordinary fact that the air of the mountains has a wonderfully refreshing effect upon constitutions enfeebled by pulmonary disease, and of my own knowledge, I could mention a hundred instances where persons whose cases had been pronounced by eminent practitioners as perfectly hopeless have been restored to comparatively sound health by a sojourn in the pure and bracing air of the Rocky Mountains and are now alive to testify to the effects of the reinvigorating climate. Although best known for his book Commerce of the Prairies, Josiah Gregg had many connections to the Santa Fe Trail through his family, and he first joined a caravan in 1831 to restore his health. Gregg, himself a tubercular dyspeptic, noted that Prairies have become very celebrated for their sanative effects – more justly so, no doubt, than the most fashionable watering places of the North. Most chronic diseases, particularly liver complaints, dyspepsia, and similar affections, are often radically cured, owing, no doubt, to the peculiarities of diet and the regular exercise incident to prairie life, as well as to the purity of the atmosphere of those elevated unembarrassed regions. An invalid myself, I can answer for the efficacy of the remedy, at least in my case.”

Josiah Gregg was the fifth of eight children. As a young man, he developed an interest in medicine and was sent to medical college in Philadelphia, where he became a doctor. After receiving this qualification, he returned to Jackson County, Missouri, to practice medicine. Gregg was also aware that the trail had helped relieve some people afflicted with tuberculosis, so he joined a caravan bound for Santa Fe in 1831. He participated in the Santa Fe trade from 1831 to 1840. His book Commerce of the Prairies, one of the most significant accounts of Santa Fe trade, was first published in two volumes simultaneously in New York and London in 1844. This famous account of the Santa Fe trade incorporates details about the history of the trail, statistics of the trade, details of the American Indian peoples encountered along the route, and information about the Mexican people, in addition to a geographical description of the country at that time.

Another individual who became associated with the trail is Kit Carson. Carson traveled the Santa Fe Trail for the first time in 1826 at the age of 16 and was closely associated with the forts along the trail in his later life. His first journey ultimately led Carson to California since, en route, he met Ewing Young, a western trader and trapper, whom he accompanied to the Rocky Mountains’ fur country. In 1830, he accompanied a second trading party to the central Rocky Mountains, where he lived as a mountain man for the next 12 years. During that time, he married an American Indian, and they had a daughter. In 1841, he became a hunter for Bent’s Old Fort in Colorado. While visiting relatives in Missouri in 1842, Carson met Lieutenant John Charles Fremont, who enlisted his services as a mountain guide and adviser on two westward expeditions. Carson served in California during the Mexican-American War and was a guide for the Army under the command of General Stephen Watts Kearny on its route to California.

Hispanic merchants were especially significant to the trade during the trail’s early years. By the end of the 1830s, several wealthy traders from Chihuahua, Sonora, and the Santa Fe area had established business relationships with suppliers in the eastern United States and Europe. They regularly traveled between Mexico and the United States with trade caravans, buying goods directly from eastern wholesalers and transporting the bulk of goods between New Mexico and Missouri. Mexican merchants transported merchandise to Missouri, opened stores in Santa Fe, and transshipped goods south into Chihuahua and central Mexico. Many Mexican merchants viewed the Santa Fe Trail as only a portion of a much more extensive trade network connecting to the eastern US and even to Europe. Specifically, Mexican merchants from Chihuahua, Durango, and El Paso del Norte viewed Santa Fe and the trail merely as one phase of a corridor of international commerce. Their perspective of the Santa Fe Trail is emphasized by the continuation of trading ventures during the Mexican-American War despite being labeled “greasers” and traitors by some of their compatriots. When threatened, Mexican merchants protected their investments in the Santa Fe trade by volunteering military service and making financial contributions to resist disruption of this type of commerce by Texans, American Indians, and Americans. Among the Hispanic merchants known to have been involved in this trade were the Chaves family, the Otero family, the Delgado family, the Manzanares family, Manuel Alvarez, Don Antonio José Chávez, Juan B. Escudero, Ramon García, Pedro Olivares, Estvan Ochoa, Juan Otero, Juan Perea, Estanislao Porras, and J. Calistro Porras. Many Mexican families sent their children to schools in the eastern United States, further emphasizing that the Santa Fe Trail was a means of commercial trade and cultural and international exchange.

By the early 1840s, as noted above, New Mexican and interior Mexican merchants played significant roles in the Santa Fe trade. Manuel Alvarez, a native of Spain, was one of the Hispanic merchants who viewed Missouri as “a mere way-station” on a commercial trail that led from New Mexico to Europe and various points in between. Alvarez operated a store in Santa Fe from 1824 until he died in 1856. He succeeded Ceran St. Vrain as a U.S. commercial agent in Santa Fe in 1839. Alvarez made several buying trips to eastern markets, including trips in 1838-1839, 1841-1842, and 1843-1844. Upon his return from a business trip to the eastern United States in August 1843, Alvarez was prevented from reentering Mexico because Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna closed all northern ports of entry into the country. As a result, Alvarez went to England, Spain, and France via Chicago and Philadelphia and departed from New York. Throughout his travels, he purchased goods and kept abreast of events in New Mexico. Alvarez conducted most of his business through the London-based firm of Aguirre, Solante, and Murrieta, which acted as his agent. He deposited $3000 in a London bank, using the interest as payment for goods purchased abroad. Despite reopening the northern ports of entry into Mexico, Alvarez did not hasten his return to Santa Fe. Instead, he returned to New York on May 1, 1844, purchasing an additional $4000 worth of merchandise. Allowing for brief sojourns in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, Alvarez arrived in Missouri around June 1, 1844, where he remained for an additional two-and-a-half months, arranging shipment of his merchandise from Independence, Westport, and St. Louis to Santa Fe. Alvarez personally arranged the transportation of his goods over the Santa Fe Trail with Charles Bent, whose shipping company transported the goods from Independence to Santa Fe for nine cents per pound. The types of merchandise Alvarez had transported included textiles, sewing utensils, lace, buttons, combs, shovels, knives, and belts – some of which he had acquired from the New York-based firms of Hugh Auchincloss and Sons; Lockhart, Gibson and Company; Walcott and Slade; Robert Hyslop and Son; William C. Langley; and Alfred Edwards and Company.

Alvarez arrived in Santa Fe in late October or early November 1844, and the goods he had purchased in London and New York arrived in Santa Fe on November 3. Alvarez went to New York and Philadelphia the following year to purchase more goods, and no doubt, he encouraged others to follow his example. Like many other Mexican traders, Manuel Armijo traveled to St. Louis and the eastern United States to purchase goods he had transported from Independence to Santa Fe over the trail. Armijo also conducted business with the New York-based firm of P. Harmony’s Nephews & Company. In 1842, he lost between $18,000 and $20,000 worth of merchandise when the steamboat “Lebanon” sank “in five feet of water some 50 miles below Independence, Mo.” Another trader, Manuel X. Harmony, traveled from New York over the Santa Fe Trail to Santa Fe and Chihuahua with a caravan of his goods. Mexican merchants experienced threats similar to those encountered by American merchants. The first Mexicans robbed on the Santa Fe Trail are believed to be Ramon García from Chihuahua and an unnamed Spaniard in the employ of William Anderson; both were robbed in 1823. Don Antonio José Chávez, a New Mexican engaged in the Santa Fe trade, operated his family’s store at the southeast corner of Santa Fe Plaza. Chávez made several trips on the Santa Fe Trail before he was robbed and murdered. Chávez departed Santa Fe in February 1843 with five servants, $12,000 in gold and silver, and some bales of fur. The small trading party reached Owl Creek (now Jarvis Creek) in Rice County, Kansas, where the traders were robbed, and Chávez was murdered by John McDaniel and a band of men claiming to be in the service of the Republic of Texas.

American Indians and the Santa Fe Trail

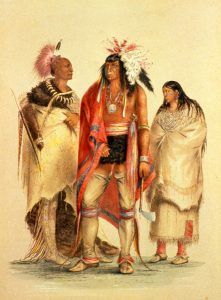

Several American Indian tribes were directly or indirectly tied to the Santa Fe Trail, either by residing in the land crossed by the trail or because their nomadic lifestyles routinely brought them into close proximity to the trail. Through the negotiation of treaties in 1825, the United States Congress officially recognized the presence of the Sioux, Cheyenne, Crow, Osage, Kanza, Otoe & Missouri, Pawnee, and Makah, but according to Augustus Storrs, Arapaho, Snake, Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache were also very present in the land around the trail. The treaties granted rights-of-way to the US to establish a road between Mexico and Missouri. Though written by the US negotiators, these treaties and agreements with the American Indians contained wording that suggests the two parties viewed each other amicably at the beginning of the trade.

As previously mentioned, Euro-American and Spanish goods that increasingly became available to American Indian groups were generally considered beneficial, as these goods often made traditional tasks easier or allowed these tasks to be accomplished more efficiently. Trading posts such as Bent’s (Old) Fort were constructed for the primary purpose of trading with the American Indians in the region. Built by Mexican laborers employed by brothers Charles and William Bent and partner Ceran St. Vrain, Bent’s Fort was completed in 1834. However, it was an active trading post in late 1833 and continued through 1849. The business consisted of trade in buffalo robes, furs, and horses and transport of Euro-American trade goods into New Mexico. The fort became a focal point of interaction between Hispanic, Euro-American, and the various Plains Indian tribes, including the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Arapaho, Comanche, Sioux, and Snake. Most of the tribes were, if not friendly, not openly hostile to the traders. fact, in his Congressional testimony in 1825, Storrs only attributed open acts of hostility to the Comanche and Pawnee – two tribes whom other Indians and the Mexicans knew to assert their power by raiding even before the opening of the Santa Fe trade. The Comanche, especially, was a dominant force in the Southwest starting around 1700. A result of raids and killings by Comanche or Pawnee Indians was that American traders, in particular, began to view all Indians as unfriendly. Storrs notes an event that occurred in 1823 where 40 horses and mules were stolen in Osage Territory by the Comanche. Because of the location, the Osage, who were generally friendly toward the Americans, were blamed for the robbery until the truth was discovered the following summer. Events like this happened often.

The popular belief among Americans at the time, as echoed in Congressional testimony by Storrs, was that American Indians hardly ever risked the lives of their warriors unless it was for revenge or in a state of open warfare. What was not understood was the larger truth that warriors willingly risked their lives to protect their tribes from other Indian raiders or from non-Indian travelers, who often unjustly reacted to attacks against them. Josiah Gregg alluded to this when he wrote that peaceful relations between Indians and traders were short-lived: It is significant to be feared that the traders were not always innocent of having instigated the savage hostilities that ensued….Instead of cultivating friendly feelings with those few who remained peaceful and honest, there was an occasional one always disposed to kill, even in cold blood, every Indian that Though Gregg understated the situation, retaliatory actions to Indian hostilities appear to be the Americans’ – military and traders – strategy throughout the trade. This reaction violated the wording in many agreements between the US and the tribes, which protected the tribal members in the event of hostilities towards them by travelers and traders. Still, the tribes were most often considered at fault.

Partly in response to the growing tensions between the traders and the American Indians, the first military post was soon established. Colonel Henry Leavenworth founded Fort Leavenworth, the first permanent fort in Kansas, on the west bank of the Missouri River on May 8, 1827. Established to guard the Indian frontier, the post also served to protect the rights of American Indian tribes, regulate trade and contact, garrison troops who protected travelers on the Santa Fe Trail, and generally preserve the peace on the frontier. The fort was the headquarters for military commanders in the Department of the Missouri and later was the general depot for supplies to all military forts and camps in the West. In May of 1834, the War Department designated Fort Leavenworth as the regimental headquarters of the 1st US Dragoons, and upon arrival of Dragoon Companies A, C, D, and G in September of that year, Fort Leavenworth became headquarters. In 1835, Colonel Henry Dodge led an expedition of dragoons to the Rocky Mountains. He held council with numerous Indian tribes along the way, even reporting back to the War Department on the state of land improvement for tribes that received allotments. Leaving Fort Leavenworth on May 29, Dodge and three companies of dragoons, numbering some 125 men, headed toward the Platte River, which they followed to the mountains. The group returned through the Arkansas River and Santa Fe Trail through Kansas, arriving at Fort Leavenworth on September 16 after a three-month trip of more than 1600 miles. One member of the party, Samuel Hunt, died and was buried along the trail in Osage County near the Soldier Creek Crossing.

One post along the Missouri River could do only so much to protect traders on the trail. In 1827, a group of Pawnee Indians attacked a returning party of traders and stole 100 heads of mules and other livestock. In 1828, near the present border of Oklahoma and New Mexico, two members of a returning wagon train, Robert McNees and Daniel Munro, having gone ahead of their caravans, were attacked while they slept; McNees died immediately, but Munro died a few days later. Their deaths were avenged later on that return trip when traders killed all but one of a group of American Indians they encountered at the crossing of a small tributary of the North Canadian River. The fact that these slain Indians – the tribe of which is unknown – were within such close proximity to the wagon train seems to indicate they were not the ones who attacked the traders.

The retaliatory killing of American Indians, regardless of guilt, seems to be an occurrence that happened often. The first of six Santa Fe Trail escorts preceding the Mexican-American War was assigned to the Army in 1829. Although the US government’s policing of the trail suggested that every man carry a gun, in 1829, newly elected president Andrew Jackson declared that an escort or outriders should be provided. This first military escort comprised Brevet Major Bennet Riley and 200 troops from Companies A, B, F, and H of the 6th US Infantry. Riley’s party hauled a six-pound cannon pulled on a mule-drawn carriage and 20 wagons and four carts of supplies and rations drawn by oxen. This was the first documented use of oxen on the Santa Fe Trail. After rendezvousing with traders at Round Grove in Johnson County, Kansas, the soldiers marched ahead of the civilian freight wagons to the vicinity of Chouteau’s Island in the Arkansas River in Kearny County, Kansas. At that time, the river in this vicinity marked the boundary between the United States and Mexico, so the soldiers could not continue the escort farther down the trail. The caravan experienced some conflict with Indians, most likely Comanche or Pawnee, soon after departing from the Arkansas River and continued to experience harassment for the next month until a group of approximately 120 Mexican hunters joined the party. On the return trip, the caravan was escorted by a group of Mexican soldiers.

Soldiers periodically provided escorts for trading parties along the trail during the next several years when the need arose and orders were issued. The second military escort along the Santa Fe Trail was not provided until 1833. In 1832, President Andrew Jackson signed an act to raise a battalion of Mounted Rangers, predecessors of the 1st US Dragoons (later the 1st US Cavalry), for one year. The battalion, consisting of six companies of 110 men each, was under the command of Major Henry Dodge. Captain Matthew Duncan and Company F of the Mounted Rangers reported for duty at Fort Leavenworth in February 1833. One month later, on March 2, 1833, President Jackson authorized raising a regiment of dragoons and discharging the Mounted Rangers. Major Dodge remained commander of the newly formed dragoon regiment, the 1st US Dragoons. In 1833, Captain William N. Wickliffe, a few 6th US Infantry soldiers, and Captain Matthew Duncan’s company of US Mounted Rangers escorted a caravan to the international border. A detachment of dragoons under Captain Clifton Wharton provided this service the following year. Among the caravans protected by the dragoons that year was a wagon train composed of 80 wagons, $150,000 of trade goods, and 160 men, including Josiah Gregg. Later, in 1834, a decision was made to eliminate the protection of caravans unless a general American-Indian war occurred.

A series of Indian Trade and Intercourse Acts were enacted between 1790 and 1847 to improve relations with American Indians by granting the United States government sole authority to regulate interactions between Indians and non-Indians. In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. As a result, more than 80,000 individuals within tribes residing east of the Mississippi River were forcibly removed to reservations in present-day eastern Kansas and Oklahoma. Within the next few years, Congress passed additional legislation governing Indian-American relations. This included legislation intended to preserve the peace, restrict contacts between Americans and American Indians, regulate trade with Native peoples, and allow the military to enforce the act. A renewal of the Indian Trade and Intercourse Act in 1834 designated all US lands west of the Mississippi River (except Louisiana, Missouri, and Arkansas Territory) as Indian Territory. Except for the military and missionaries, Americans were precluded from settling on or purchasing Indian lands. Fort Leavenworth soon adopted the added responsibility of protecting the rights of newly relocated tribes in the region. As a result of an 1834 act regulating the Indian Department, Fort Leavenworth also served as a central distribution point for cash annuity disbursements paid to these Indian tribes as established in treaties.

The Republic of Texas

Not until the spring of 1843 was another escort provided along the trail. In the meantime, a new threat to Santa Fe travelers emerged. Texas declared its independence from Mexico in 1836, and the bitter animosities that developed were cause for concern. The Republic of Texas requested annexation by the United States, but President Jackson refused. Texans, under the leadership of President Mirabeau B. Lamar, who was elected in 1838, sought recognition of the Republic by the world’s leading powers in the hope that it would force Mexico to acknowledge the Republic’s independence. This acknowledgment was not received, so this group of Texans attempted to expand Texas’ border to the Pacific coast. This made the conquest of New Mexico their first objective. In 1841, a Texan expedition set out for Santa Fe to secure military, political, and economic control over that city despite its stated objective of trade. The members of the expedition were forced to surrender and serve a one-year jail term. The Republic of Texas authorized Jacob Snively and the “Texas Invincibles” to seize, through “honorable warfare,” the goods of Mexican traders that lay within Texas territory. However, the Invincibles’ expedition was to remain an unofficial Texan enterprise of less than 300 men comprising individuals from the Texas government and those selected by Snively. The Mexican government pressed for American protection of the Santa Fe wagon trains while the Mexican president secured safe passage from the Arkansas River to Santa Fe.

The US government responded by ordering colonels Stephen Watts Kearny and Philip St. George Cooke to furnish escorts once again for the caravans bound to and from Santa Fe. In doing so, US military escorts forced Snively and his followers to surrender. While this alleviated the threat of the ambush of Mexican traders, it meant that Mexico’s earlier fears that the Santa Fe Trail might become an avenue of conquest had now become a reality. Thus, on August 24, 1843, when the fifth military escort accompanying the Santa Fe caravan reached the Arkansas River, Mexican forces, fearing an American takeover, turned out en masse to accompany the caravan for the remainder of the route. Except for the 1829 and 1843 escorts, no Mexican protection was afforded Santa Fe caravans beyond the Upper Canadian River. Upon the return of the 1843 US escort, Colonel Cooke declared that since the Texan threat had been all but eliminated, military escorts were no longer needed.

The first decades of the Santa Fe trade saw a steady use of the 900-mile trail. Mexican and American merchants thrived from the new commercial possibilities of the trade while the Native peoples fought to retain control over their lands and ways of life. The United States’ increasing desire for control led to multiple armed conflicts with American Indians. Eventually, it melted amicable relations between the United States and its newly independent neighbor to the south. The sixth military escort – led by Colonel Kearny – in May 1845 proved to be foreshadowing the war to come the following year.

Compiled & edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Santa Fe Trail – Exploration & Illegal Trade – Pre-1821

Source: Santa Fe Trail National Register of Historic Places Nomination