Trade was an integral part of the lives of many American Indian tribes well before the opening of the Santa Fe Trail. There is a significant body of evidence indicating that since prehistoric times, communication, travel, and trade had connected the American Plains with both the Southwest and prairies to the east. Southwestern aboriginal ceramics have been recovered from sites on the Plains, while prehistoric cultural material from Plains cultures has been recovered from the southwest, such as Pecos. Puebloan architectural influence is visible on at least one Plains site, namely El Cuartelejo in Scott County in western Kansas. Tribal oral traditions and early historical accounts refer to contact and trade between southwestern horticulturalists and Plains hunters, including the exchange of corn for bison meat. Plains tribes also traded with cultures to the east, such as Mississippian peoples in the St. Louis vicinity, and stone tools from Missouri are frequently recovered in archeological sites in Kansas.

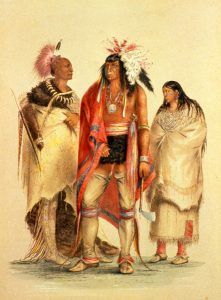

Trade fairs, hosted in Pecos, San Juan, and Taos, New Mexico were common in the late 17th and into much of the 18th centuries. Large numbers of Pueblo and Plains Indians, including the Apache, Comanche, Kiowa, and Ute, gathered at these annual fairs to exchange stone tools, foodstuffs, Native products, horses, slaves, and captured Spanish goods. These trade fairs were hosted in the summer months and witnessed the gathering – under temporary truces – of Indian tribes that often were in conflict with each other. These fairs also brought Spanish residents of New Mexico to trade with the American Indians. The Spanish, and eventually other European traders, introduced new items such as plants, animals, food, and manufactured goods that effected extraordinary changes among plains peoples. These changes were welcomed by the American Indians as the new items made traditional tasks more easily accomplished. A metal scraper allowed a woman to process an animal hide more quickly. Muslin or bed ticking made a durable and lightweight inner lining for a traditional tipi. An iron vessel, unlike the ceramic ones used for centuries, was virtually indestructible, and so it eased the ancient jobs of cooking and pot making. Further, the introduction of horses significantly altered the way the Comanche empire extended its reach by allowing more effective and efficient means of hunting, transporting, and warfaring. By the end of the 18th century, the trade fairs were less important to the American Indian economy due to large amounts of goods given by the Spanish to the Comanche and allied nations.

The approach to trade was fundamentally different to American Indian nations and to the Spanish. For American Indians, trade was more than a way to gather wealth; it firstly created and solidified attachments between the trading parties that were meant to protect their respective tribal members from any and all harm; trade made all parties kin. In contrast, the Spanish (and later Euro-Americans) were influenced by the desire to acquire wealth and thus separated personal relationships with the trading partner from the economic benefits of the trade agreement. This fundamental ideological contrast between the American Indians and the traders later led to real conflict between the two groups during the course of the Santa Fe trade.

By about 1700, most of the Indian tribes that would become familiar to travelers on the Santa Fe Trail were becoming established in the locations where American explorers would find them. During the century leading up to 1800, what would become the Mountain Route of the Santa Fe Trail, was a path that was used by fugitive Puebloan people to escape from oppressive Spanish rule. Near the east end of the trail, Missouri and Osage tribes were in what became the State of Missouri. Kanza and Pawnee tribes were just to their west in modern northern Kansas. The Wichita were located in southern Kansas into northern Oklahoma, and the Kiowa and Comanche lands were in the short grass plains in the general vicinity where the states of Kansas, Oklahoma, Colorado, and New Mexico come together. Cheyenne and Arapaho were located on the west edge of the High Plains in western Kansas and western Oklahoma. The Plains Apache were in what is now northeastern New Mexico. North of Santa Fe in the Rockies, the Ute lived on the northern frontier of the Pueblos near the westernmost extent of the Mountain Route of the Santa Fe Trail.

Before 1821, many people had followed the route to Santa Fe, or portions of it, from the American Indian inhabitants of the region to the many Spanish, French, and American explorers. Early Spanish explorers in the New Mexico Pueblo area recorded tales of the riches of Cibola and Quivira and encountered Natives of these places residing in the pueblos. Spanish explorer Francisco Vasquez de Coronado organized an expedition to the Plains in 1541 with Fray Juan de Padilla. Pedro Castaneda’s journals that he kept during the expedition indicate that they initially traversed a route to the Plains that went far south of the future Santa Fe Trail into the Texas panhandle before turning northward. They reached the Arkansas River near modern Ford, Kansas. Once across the river, the expedition generally followed the river northeast, as did the later Santa Fe Trail, to the vicinity of modern Great Bend, Kansas. The Spaniards reached their goal of Quivira at some villages in the vicinity of modern Lyons, Kansas inhabited by ancestors of the Wichita and affiliated tribes. On the return from Quivira in 1542, their route closely resembled the Cimarron Route of the Santa Fe Trail from central Kansas to Santa Fe. Spanish residents of New Spain did not officially establish La Villa Real de Santa Fe (The Royal Town of the Holy Faith) until 1609 or early 1610.

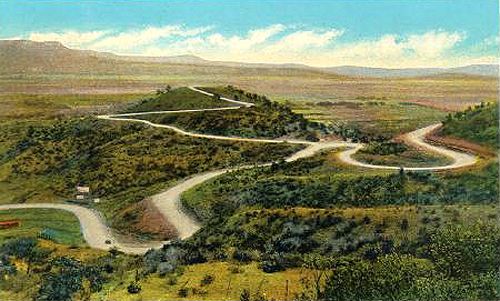

While the rocky, mountainous terrain encountered on the Mountain Route hindered access to Santa Fe from the north, several routes across the mountains existed. Among these routes were Raton Pass, San Francisco Pass, Manco Burro Pass, Trinchera Pass, and Emery Gap, with recorded use of these routes dating back to the early 18th century. During the summer months of 1706, Spanish Sergeant-Major Juan de Ulibarri followed a route similar to the Mountain Route of the Santa Fe Trail through Raton Pass to El Cuartelejo in western Kansas. Ulibarri sought to return a group from Picuris Pueblo who had fled to El Cuartelejo following the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. The Comanche discovered a better route across the mountains from west to east in the 1720s. Between the 1730s and 1763, reports exist of French traders from the Mississippi Valley supplying Comanche with arms and perhaps journeying as far as Taos, New Mexico. During the last half of the 18th century, Spaniards seemed to use the Sangre de Cristo route into the Arkansas Valley to the exclusion of all others.

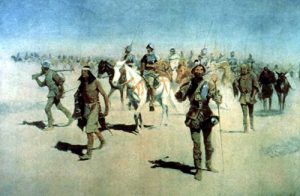

Pedro de Villasur, with an expedition of about 45 officers and soldiers, 60 Indian allies, a French interpreter, and one priest, left Santa Fe on June 16, 1720 under orders to investigate reports that the French, with whom the Spanish had been at war since 1718, were living among the Pawnee on the Platte River in Nebraska and intruding into Spain’s territory. The expedition traveled from Santa Fe to Taos, then north and east as far as Nebraska. En route, the expedition stopped at El Cuartelejo where a group of Apache joined them to act as guides. Villasur’s route through Colorado and New Mexico may have followed one similar to the Mountain Route of the Santa Fe Trail. Pawnee warriors attacked Villasur’s expedition, killing all but a dozen of the Spaniards. The Spanish blamed the attack on French influence over the Pawnee. Although the Spanish continued to be wary of incursions by the French into their territory, some trade with Santa Fe may have occurred during the 1700s by the French on the Mississippi River through Indian intermediaries.

A number of French explorers and traders, including Jean-Baptiste Benard LaHarpe in 1719 and Etienne de Veniard de Bourgmont in 1724, attempted to open trade with Plains tribes and in Santa Fe with varying results. After leaving France, with his eyes set on the Santa Fe trade, LaHarpe was employed as a concessionaire in the Province of Louisiana before putting together his own expedition. Bourgmont traded with the Missouri, Kanza, and other tribes along the Missouri and Kansas Rivers in the area that nearly a century later served as the starting points of the Santa Fe Trail. It appears that Bourgmont may have traveled as far as the vicinity of Council Grove or Lyons, Kansas on the later trail.

Some accounts exist of illegal trade between New Spain and the United States prior to Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1821. While inhabitants of New Mexico welcomed occasional traders, Spanish officials adhered to a “closed-door” policy because they feared the effects of trading with those outside of Spanish authority. However, contraband was allowed and border guards were bribable. Once inside the border, goods were often confiscated and sold by the Spanish, and the illegal traders were arrested. By the end of the 18th century, this practice was commonplace. According to Juan Paez Hurtado, the alcalde of Santa Fe, brothers Paul and Pierre Mallet with seven French Canadians arrived in Taos in July 1739 “with the intention of opening commerce with the Spaniards of the Realm.” They subsequently experienced “a few months of friendly captivity.” Nine months later they were allowed to leave. Their exact routes across the Plains to and from Santa Fe are unclear, but they may have followed portions of the later Santa Fe Trail. In 1803 the United States secured the Louisiana Territory, though not until 1819 were the boundaries of the territory settled. After 1803 trappers and traders visited Santa Fe and its environs, but legal trade between Mexico and the United States did not begin until Mexico achieved its independence in 1821.

The interest and risk demonstrated by many of these traders must have ignited Spanish curiosity because, in 1792, Pedro Vial was instructed by New Mexico Governor Fernando de la Concha to seek a route from Santa Fe to St. Louis, Missouri, which he did. Vial, a French frontiersman who had become a Spanish citizen and had experience living among Indian tribes, made a number of trips across the Plains. With just a few companions and pack animals, he undertook several explorations through the Spanish-American frontier. During the 1780s he pioneered routes between Santa Fe and both San Antonio, Texas, and a post at Natchitoches, Louisiana. In 1792 Governor Concha sent Vial from Santa Fe to open direct communication with Spanish establishments of the Illinois Indians situated on the banks of the Missouri River in the vicinity of St. Louis. On this trip, Vial and his companions were briefly held captive in western Kansas by Indians, probably either Kanza or Apache, but they were released on the Republican River in north-central Kansas. There, Vial’s party met some other travelers and continued their journey to St. Louis with them down the Republican and Missouri Rivers. A portion of Vial’s route to and from Santa Fe approximated what later became the part of the Mountain Route of the Santa Fe Trail from Hamilton County to the vicinity of Great Bend, Kansas.

The practice of illegal trade continued into the early years of the 19th century prior to Mexican independence. William Morrison, a Kaskaskia trader, sent his agent, Jean-Baptiste La Lande, overland to New Spain with a supply of trade goods in 1804. Once there, La Lande severed his connections with Morrison and used the goods to go into business for himself. After he sold the goods, Spanish authorities did not allow him to leave New Mexico. He was not the only trader who was not permitted to leave the country. James Purcell had been on a hunting-and-trapping expedition in 1802 when he was attacked by Indians and forced to retreat to Santa Fe, then not allowed to leave.

Following The United States’ acquisition of Louisiana Territory, the American military conducted and participated in numerous exploratory, mapping, and scientific expeditions in the West. One of these journeys began during the summer of 1806 when Captain Zebulon M. Pike set off on an expedition to investigate the disputed southern boundaries of this territory for the US government and report on the characteristics of the Arkansas and Red Rivers. Accompanied by a party of 22 men, Pike spent two weeks among the Osage Indians in western Missouri and visited a Pawnee village in modern southern Nebraska before heading into what later became central Kansas. In late October the party divided into two forces near the Great Bend of the Arkansas River. Lieutenant James Wilkinson and a detachment began the return trip east, traveling downriver in recently constructed canoes. Pike and 16 men continued up the river toward the mountains, traveling west along what later became part of the Mountain Route of the Santa Fe Trail. Having entered Spanish territory along the Rio Grande, Pike and his party were eventually captured by Spanish troops. Spaniards escorted Pike to Santa Fe where he saw other Americans who had been detained, including Jean Baptiste La Lande and James Purcell. Pike was later taken south to Chihuahua. He was impressed with what he saw and relayed what he had seen to others upon his return. Zebulon Pike published an account of his journey, Journal of the Western Expedition, in 1810. This publication created new interest in trading with Santa Fe, and new expeditions followed.

Several other would-be traders set out for Santa Fe in the early 19th century. Some would contend that the first truly successful Santa Fe trader was Jacques Clamorgan, a trader from St. Louis who, in 1807, departed Missouri traveling overland to Santa Fe and on to Chihuahua, Mexico. Clamorgan was thought to be successful because of his life as a Spanish subject before he became a citizen of the United States. His understanding of the Spanish culture and his strong grasp of Spanish language helped him in his 1807 endeavor. Three years after Clamorgan’s journey to Mexico, James McLanahan, Reuben Smith, and James Patterson unsuccessfully attempted trading in the region. The three men were arrested and imprisoned for several years in the Presidio of San Elizario, 17 miles downriver from present-day El Paso, Texas. In 1812 a group of ten Missouri frontiersmen, including James Baird of St. Louis, Robert McKnight, and Samuel Chambers, believing erroneously that the Mexican Declaration of Independence in 1810 under Hidalgo had removed the stringent Spanish trade restrictions, crossed the Plains in an attempt to trade with Santa Fe. The Spanish government, in compliance with its standing policy against allowing trade between its colonies and other nations, confiscated their goods. These American traders were imprisoned in Chihuahua; the last of these men, McKnight, was not released until 1821.

Between 1812 and 1815 while the United States was involved in war with England, Manuel Lisa, a Spanish-born Missouri River fur trader, wrote to the Spaniards offering to trade with them. He dispatched Charles Sanguinet toward Santa Fe with a load of merchandise with the intent to engage in trade; however, everything was destroyed in a confrontation with American Indians. Auguste P. Chouteau, a member of the famous St. Louis fur-trading family, and Jules de Mun conducted several trips to Taos over the Sangre de Cristo Mountains before being arrested in 1817. Eventually, they were allowed to return home to St. Louis. Jedediah Smith guided a pack train over what was to become the Santa Fe Trail to the Arkansas River in 1818. However, after a Spanish merchant with whom he was supposed to trade did not arrive, the unsuccessful trading party returned home. In 1819, New Mexican Governor Melgares ordered a fort built on the eastern side of Sangre de Cristo Pass, northeast of Taos. The Governor read a report that stated the Sangre de Cristo Pass was vulnerable to attack, and because of its strategic location, a few men could defeat an entire army. The fort was attacked and destroyed six months after its completion by either American Indians or Americans posing as American Indians.

Prior to the establishment of the Santa Fe Trail, New Spain’s far northern frontier had developed a unique character. The physical environment played a key role in the establishment of settlement in that arid climate, and natural materials allowed residents to construct buildings of adobe. The Spanish government offered incentives to individuals willing to settle on these frontier lands. Hispanics assimilated indigenous American Indians into these frontier societies, thus creating a “frontier of inclusion.” Historians and anthropologists have viewed New Spain’s far northern frontier as more informal, democratic, self-reliant, and egalitarian than that of central portions of the viceroyalty. However, far northern portions of New Spain developed a strong Hispanic urban tradition with restrictions on trade and travel. Most of the populace of northern New Mexico was fully occupied merely trying to grow enough crops to survive and to raise sheep. Both sheep and wool were commodities that could be traded in markets to the south, but woven textiles were increasingly popular as trade items to the south. Up until 1821, New Mexico received nearly all its other goods and supplies from the interior provinces. However, distance, difficult terrain, and government restrictions isolated Santa Fe from markets farther south. In addition, merchants in Chihuahua controlled trade to the New Mexico frontier, and their practices and manipulation of markets and currency further oppressed settlers in the northern settlements. By 1803 goods imported from Chihuahua to New Mexico were valued at more than $100,000, but the province’s exports were averaging much less than this figure. As a result, the merchants in Santa Fe were constantly in debt, and the general populace suffered a perpetual shortage of manufactured goods.

Rather than establishing new roads between New Mexico and the United States, large segments of the Santa Fe Trail followed pre-existing paths created by earlier explorers and would-be traders.

Compiled & edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated December 2020.

Also See:

Early Traders on the Santa Fe Trail

Santa Fe Trail – Highway to the Southwest

International Trade on the Santa Fe Trail, 1821-1846

Source: Santa Fe Trail National Register of Historic Places Nomination