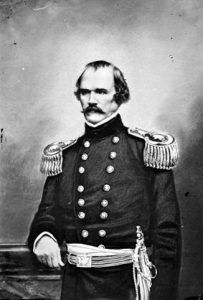

By General Randolph B. Marcy, Published in 1888

The rapid and thorough reclamation of our Western possessions from the control and domination of the Indians and the magical transformation of this vast expanse of wilderness from a theatre of barbarous warfare into thriving cities, villages, and farms, the occupants of which are provided with peaceful and happy homes, are doubtless without a parallel in the annals of civilization.

The purpose of this paper will be to elucidate this subject, mainly deduced from personal observations during half a century’s service in the United States Army, for the most part in the wilds of the West.

As during this period, I was often called upon to conduct extended explorations involving long marches and occasional severe hardships and privations, leading me into the most unfrequented recesses of the mountains and plains, it has occurred to me that a succinct narration of some of the most notable incidents attending this era of my somewhat adventurous career might not prove void of interest to the reader, and serve to convey a general idea of the topographical, agricultural, and other characteristic features of that important section of our extensive domain.

In the execution of this purpose, I remark that my military service commenced in Wisconsin when there was no cultivated farm throughout the entire area of that large and preeminently attractive agricultural territory. Neither was there a road leading from my station at Green Bay in any direction, so the only practicable method of penetrating the adjacent forests was by following crooked and narrow Indian trails. Indeed, the whole country west of Lake Michigan, as far south as Milwaukee, was at that time a vast primeval forest without a wagon trace, clearing, or house, and the only respectable tenement at the incipient hamlet of Milwaukee was that of Solomon Juneau, a most genial and hospitable French Indian trader, who through preemption secured a patent to a quarter section of ground embracing the present site of that magnificent city.

When I first reached Wisconsin, the Western border settlements did not extend beyond the Mississippi River. But from that time to the present, a movable cordon of military posts has been kept up in advance of the outer pioneers, thereby interposing an effective barrier against the incursions of blood-thirsty Indians, who have but recently ceased their barbarous efforts to obstruct the advance of civilization. It is believed that without the protection thus afforded, it would have been impossible to have forced our settlements much beyond the Mississippi River for many years to come.

In 1838, I visited Fort Snelling, Minnesota, only five miles from where the proud and beautiful cities of St. Paul and Minneapolis now stand, with a population of 100,000 each, and where there was not then a white human habitation.

Indeed, I saw but three cabins between Fort Snelling and Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, a distance of some 300 miles along the Mississippi River, whereas numerous large and flourishing towns and highly cultivated plantations now skirt both banks of the river throughout the entire distance.

In 1848, I was ordered to the Indian Territory, where I served for several years among the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Cherokee, numbering in the aggregate about 50,000 souls. They were, at that time, through the benevolent efforts of missionaries, considerably advanced in civilization and enlightenment, having abandoned their hunting proclivities and adopted agricultural avocations. They had churches and schools, which were well sustained, and many of them were fairly educated, lived in comfortable houses, and produced abundant crops. Some of them cultivated large and remunerative cotton plantations.

The Choctaw and Chickasaw Reservations, united, are some 300 by 200 miles in extent, embodying woodlands and beautiful prairies, all well-watered, and the soil eminently productive and admirably adapted to the requirements of the husbandman. While there, in 1849, I was ordered to escort a large party of emigrants from Arkansas to New Mexico en route to California. Our course, near the 35th parallel of latitude, led us for the first 200 miles through a heavily timbered forest, when we emerged into the Great Plains and followed the Canadian River Valley for 400 miles over an unexplored, arid, and sterile region, and thence through a mountainous section until we arrived at Santa Fe, 820 miles from the point of our departure at Fort Smith.

We ascertained here that the emigrants could not take their wagons through to California without turning down the Rio Grande 300 miles to the southern Gila route, the only practicable road then known. It appeared that the authorities at Washington imagined there was a wagon trail from Santa Fe direct to San Francisco, and my orders were issued under that misapprehension.

As it was evident the road we had made would no longer be traveled by California emigrants, being 200 miles out of the direct course, I resolved to accompany the party to the Gila Road and endeavor to find a practicable wagon route from that point back to Arkansas. With a Comanche Indian, who assured me he could pilot us through to Texas, I ventured out from Donna Anna on the Rio Grande and marked out an excellent road to Fort Smith, a distance of 904 miles, 500 of which was through an unexplored section of the country, and emigrants afterward traveled this road for several years, and the Texas Pacific Railway passes near the same route now. This road from Fort Smith crosses the Red, Trinity, Brazos, and Colorado Rivers of Texas, traversing a most fertile region as far as the 101st degree of longitude or about 120 miles beyond the western limits of arable land upon most of the other Pacific roads; but from thence onward, through Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona, the country, for the most part, is sterile and worthless, except for grazing.

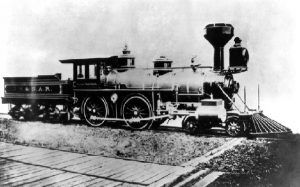

Four different trunk railroads, with numerous auxiliary Eastern branches, have been completed entirely across the continent within the limits of our possessions. Yet it is doubted if the public generally entertains a correct idea of the agricultural capacity of much of the country over which these continental thoroughfares pass. Many seem still to be of the opinion that our border territories possess all the elements for making rich grain-producing States, but this conclusion is erroneous, as my own observations, while crossing the Rocky Mountain chain at several different points between latitudes 32 and 48 north, conclusively show that near the center of the continent a broad belt of elevated arid tablelands is found extending from latitude 31 to 45, and from longitude 100 to 120, where, on account of the infrequency of summer rains, crops can rarely be produced without artificial irrigation.

The scarcity of permanent water renders this tillage method impracticable, except along the few streams from which the water can be turned out over the bottoms or brought in ditches from adjacent mountains. Besides. there is no woodland throughout this entire tract save narrow fringes of cottonwood skirting the banks of watercourses; in the mountains, pine timber is found, some of which makes fair lumber, but there is no hardwood in this belt, except occasionally a few small scrubby oaks are met with. But while hunting in these mountains during every September for the past 14 years, I have never seen an oak or another hardwood tree sufficiently large, long, and straight to make a decent wagon tongue.

In view of these facts, it will be apparent that the idea of expanding our Western frontier settlements beyond Texas, Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska in anticipation of making other agricultural states of like productive capacity is altogether fallacious. The history of New Mexico, which has been occupied by the Spaniards for more than a century and where nearly all the available land has been continually cultivated ever since gives a forcible illustration of this. Besides, ever since that territory was ceded to the United States in 1848 by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, it has been open to occupation by our citizens, yet but very little has been added to its area of cultivation or to its population within that period.

I received orders from the War Department in 1852 to explore the Red River of Louisiana from the upper settlements upon that stream to its sources. There was then no record of any men ever having reached the head of this important tributary of the Mississippi, which is navigable for steamers 1500 miles above its mouth. It was, however, supposed to take its rise in a mountainous region east of New Mexico.

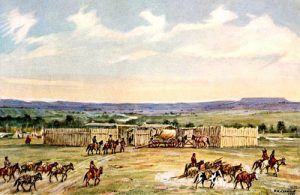

Red River in Texas

The navigable part of Red River meanders through heavily timbered alluvial bottomlands of the most prolific character, yielding enormous crops of cotton and cereals without artificial irrigation. Our explorations commenced above the timbered section, where the soil was not so deep as below, and it became more arid and sterile as we ascended until we reached the point where it debouched from the great Llano Estacado through a gigantic canyon at least 500 feet deep, and here the water was very bitter and unpalatable, resulting from the decomposition of gypsum, through an immense deposit of which the river flowed for seventy miles, and which the eminent geologist Dr. Hitchcock pronounced to be, with one exception, the largest body of that mineral in the known world. As soon as this deposit was passed, the water became pure and free from salts.

While serving in Florida during the Seminole War in 1857, my regiment was ordered to march from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to Utah for the purpose of aiding the authorities in enforcing the laws of the United States against their infractions by the Mormons.

We left the Missouri River, with large trains of ox teams transporting our supplies, on July 22 and proceeded over the route at the rate of only 14 miles a day until we reached the Rocky Mountains, where we encountered cold storms, with so much snow that our wearied cattle, exhausted from overwork and the absence of grass or other forage, soon began to break down and die by the hundreds, which finally compelled us to stop for the winter at Fort Bridger, Wyoming 150 miles short of our original destination at Salt Lake City, Utah.

The Mormons at that time evinced the most implacable hostility toward us, destroying three of our large supply trains, and orders from their highest authorities, which I captured from one of their armed parties, directed them to destroy the roads, burn the bridges and grass in front of us, and impede our movements in every way in their power. They had also fortified the deep mountain gorges through which they expected us to pass and, in their Temple, threatened us with war to the knife should we attempt to approach Salt Lake City.

I saw in their paper, the Deseret News, the quotation from a discourse delivered about that time in their Temple by Heber Kimball, one of the most belligerent of Brigham Young’s 12 disciples, in which he said: “We are told in the good book that we should love our enemies, but I feel to hate my enemies, and I hate the President of the United States. And, my brethren, they tell us that the President is sending out an army of 2500 men to chastise these people. Good God! I have wives enough to whip out that army.” This did not, however, give us much uneasiness, and if our animals had held out, we would doubtless have pushed forward at once, which might have brought on a sanguinary war with those people.

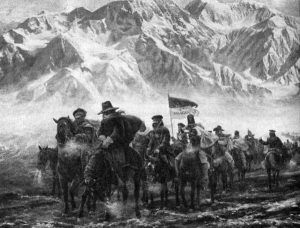

We reached Fort Bridger about the middle of November, having been nearly four months on the road. This, with the destruction of our trains, consumed the greater part of our winter supplies, and as they could not be replenished from the Missouri River before the following June, General Johnston, the commander, determined to send a detachment directly over the mountains to New Mexico, from whence it was believed supplies could be obtained earlier than from further east. I was detailed to conduct this expedition, and with an old mountain guide and forty enlisted men, with sixty-six pack-mules, we left Fort Bridger on November 24 and arrived at the base of the mountains near Grand River without difficulty, finding but little snow, and plenty of grass for our animals for the first 200 miles. But in advance of us, the prospect did not appear so encouraging, as the lofty peaks of the Rocky Mountains rising into the clouds directly across our course were covered with snow. From this point onward, we encountered the most formidable obstructions; perhaps the mention of a few incidents relative thereto may not overtax the reader’s indulgence.

We here met with a band of Digger Ute Indians and endeavored to hire their chief to guide us to the summit of the mountains, offering him the price of four horses. But he refused, saying he would not attempt it for everything we possessed; that he crossed these mountains in the autumn and found snow two feet deep then, but it might be six feet now. He would, therefore, advise us to remain with him through the winter or go back where we came from, as we would inevitably perish if we continued on.

Notwithstanding his gloomy prediction, we resumed our march the following day but soon struck snow that materially impeded our progress, and it continued to increase as we advanced until, after a few days, it became so deep that our mules could no longer wade through it, and obliged me to place the men in advance to break a track for them.

The snow at this time was five feet deep and so dry and light that a man could not walk upright without sinking to his waist at every step; neither could snowshoes be used, and the only alternative was for the leading men to lie down and crawl over the snow, placing their hands and feet in the same holes, so that when four or five had started in single file the track bore up the others walking up-right, and after all had passed, the snow became sufficiently packed to support the mules. Thus, we struggled on at the rate of only three or four miles a day until, at length, our provisions were consumed, and our poor animals, having no forage but bitter pine leaves, began to falter and die from starvation. But they thus secured us from starvation, as we had no other sustenance for fifteen days save the lean flesh cut from their dead carcasses. We had no sugar, tea, coffee, salt. or tobacco but suffered most for want of the last two.

While thus forcing our way onward, and encouraged by the confident assurances of our guide that we would soon reach the summit of the mountains, one of our herders, a half-breed Mexican, who was accidentally picked up just as we were leaving Fort Bridger, came to me, and said if I was aiming for the Cochetopa Pass, we were then going directly away from it; that he had been there before, and was familiar with the country.

This startling announcement, as may be imagined, caused me most serious apprehension and alarm, as up to that time, I had placed implicit reliance upon the knowledge of our guide, whom I at once called up and questioned closely, and he finally admitted that as he had never passed over these mountains except in summer, their appearance now, enveloped in deep snow, was so different from what it was whenever he had seen them before that he was not altogether certain he was upon the right course; still, he believed lie was correct.

This evidence of a lack of confidence on his part was, to me, a matter of the most intense perplexity and anxiety, as I had the best reasons for believing the pass we were aiming for to be the only one for several hundred miles where these mountains could be crossed in midwinter. Indeed, General Fremont, some years before this, in the winter season, attempted the passage of this range of mountains forty miles south of the Cochetopa Pass and lost all of his animals and several of his men, obliging him to abandon the enterprise and return to Taos, the point of his departure. In view of the momentous consequences involved in the dilemma, I asked the herder if he was absolutely certain as to the correctness of his statement. If so, and lie was willing to act as a guide, I would give him $50 dollars in addition to his wages. But, I added, if at any time I discover you are not leading us right, I shall hang you to the first tree we come across as certain as you are living. He replied that lie was willing to risk his neck upon it, and he was received as our guide from that time and doubtless saved all our lives, as without him, we would all inevitably have starved to death.

Shortly after this, from the summit of an elevated peak, he pointed out to me a depression in the mountain chain to our left, about thirty miles distant, which he said was the Cochetopa Pass we had been so anxiously looking for. But it required ten days of the severest labor to reach it. We had not for twenty days seen the least indication of a road or trail, but here we discovered evidence that a white man had been here before us in some distinct blazes smoothly cut by a white man’s ax upon the trees in the pass. In looking east from the summit of the great continental divide at this point, we saw in the distance a vast plain bounded by a chain of lofty mountains, extending south as far as the eye could penetrate, and this our guide informed us was within the valley of the Rio del Norte, now called San Luis Park.

He also pointed out a far distant peak, at the foot of which, he said, Fort Massachusetts (now Fort Garland), Colorado was situated; and as this was the first place from which we could expect to procure supplies, I dispatched two men with the only serviceable mules we had, giving them orders to hurry through to the fort, with a note to the commanding officer urging him to send us relief as soon as possible, as we were starving. They started at once, the snow diminished a little in depth, and we followed on as fast as the crippled condition of our animals would permit and, at length, reached the plain we had seen from the top of the mountains.

Ten days had now elapsed since our messengers left for the fort, and as nothing had been heard from them, and fresh snow had obliterated their tracks, I was fearful they had perished or last their way, but about sunset, two horsemen were discovered in the distance rapidly approaching, and to our great relief they soon came galloping into camp on fine fresh horses and proved to be our long-looked-for messengers, and I have never witnessed such an exhibition of joy as was evinced by the party on that occasion.

The ruling propensity of men who are accustomed to tobacco received a forcible illustration at this time, as one of the messengers from the fort, before dismounting, threw a long plug of chewing tobacco into the crowd, where it was soon torn to pieces and demolished; but it so happened that one man who did not succeed in getting a taste offered ten dollars to another for a single quid, which, being about the amount of a months pay of the soldier, was, I thought, quite an extravagant offer.

At another time, while we were in the deepest snow and had stopped for a few minutes to rest and warm, I filled my pipe from a very small piece of tobacco, the last remaining fragment in the party, and observed the anxious look of one of my very best men who stood near me, I held the precious morsel out to him and asked if he would not take a smoke. He replied, “No, thank you, captain; I never smoke.”

“Well,” I said, “you are fortunate not to indulge in this habit when tobacco is so scarce.” He said nothing for a moment, then added, “I sometimes chew.”

“Help yourself,” said I, which he did, and exclaimed, with a most grateful expression, “I never tasted anything so good in my life, captain.”

We resumed our journey the following morning and, during the day, met the supply wagons, which were at once turned into a camp when the soup was made for the party and a guard placed over the provisions to prevent the men from overeating, which in their famished condition might have serious consequences.

The commanding officer at Fort Massachusetts had kindly sent me a jug of brandy, and as soon as we reached camp, I gave each one of the men a small drink, which in a short time made them very drunk, but the soup soon sobered them.

Notwithstanding my precautions, five of the men got at the provisions during the night and were almost insensible the next morning from excruciating pains in the stomach, the effects of their imprudence. Medicine was given for their relief, but one of them, Sergeant Mortona, the most excellent soldier of the 10th infantry, died during the day, and it was with great difficulty that the lives of the other four were saved.

Four days afterward, we marched into Fort Massachusetts, receiving a hearty welcome from the officers and men of the garrison. But, judging from the quizzical expression of their countenances and their manifest efforts to smother their risible impulses, they evidently looked upon us as the leanest, ragged, and untidy uniformed specimens of regulars they had ever encountered, which was not at all surprising, as but few of the party had any caps, their shoes were worn out, and their feet bound with mule hides or fragments of blankets, their trousers worn off below the knees by the snow crust and brush, and the few greatcoats remaining were materially razeed for repairing rents in other garments.

We had been 51 days in making the journey from Fort Bridger, about 500 miles, the greater part of the way over elevated mountains buried in deep snow, without the slightest trace of a road, pathway, or trail, and not a white man or house was met with during the entire trip. We were all greatly emaciated, and twelve of the soldiers had their feet and legs frozen so badly that they had to be carried upon the poor mules, only eighteen of which remained alive at the terminus of our journey.

From Fort Massachusetts, we proceeded on to Santa Fe, and after securing such supplies as were required for our operations in Utah, set out on our return by a different route, passing through the Raton Mountains and near Pikes Peak to the divide of the Arkansas and Platte Rivers at Squirrel Creek, where, on the first day of May, we encountered the most terrific storm I ever witnessed.

The wind blew a furious gale for thirty hours, accompanied by a dense, sharp, blinding snow, which fell to a depth of three feet, causing two of our herders to perish but a short distance from the camp, and another was found crawling around on his hands and knees, in a state of mental aberration, after the storm ceased.

From there, we followed down Cherry Creek to its confluence with the South Platte River, which we found too deep and rapid for fording and were obliged to halt for several days and build a boat to make the crossing safely. While we were here, one of our teamsters and old trapper washed out some gold from the sands of Cherry Creek, and shortly afterward, at his request, he was discharged and left us.

There was not then a white man living within one hundred miles of this place, but in a few weeks, miners began to arrive from the East (probably guided by our discharged employee) and pitched their tents upon the same ground we had occupied, and that identical spot is at this time embraced within the limits of a most beautiful and flourishing city of 50,000 inhabitants and is called Denver.

From there, we encountered no further obstructions, passing around the foothills, up the Cache la Poudre River, and down Bitter Creek, where no wagon ever passed before, and arrived at Fort Bridger on June 2.

As the different transcontinental railroads that have been completed afford easy access to the greater part of our Western domain, it has occurred to me that a description of the country traversed by these thoroughfares would give the farmer or stock-grower a more accurate knowledge of the comparative advantages of different sections than could be derived from other sources. I, therefore, adopt this method of giving my own views on the subject.

Of the three different railroads extending from the Mississippi River to the New Mexico, Galveston, Harrisburg, and San Antonio road, leaving New Orleans, passes Galveston and San Antonio and runs through southern Texas to El Paso on the Rio del Norte. It traverses a rich farming section as far as San Antonio when it enters a more arid and barren region, which for the most part is only adapted to grazing purposes, and thence on to El Paso, but few arable areas are found. The Texas Pacific Railroad connects with Eastern roads at Dallas, Texas, from whence it passes through central Texas to El Paso, near the route I explored in 1849, some account of which has already been given in this paper. The third road, called the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, leaves the Missouri River at Topeka and Kansas City, traversing a very rich agricultural district of Kansas that is rapidly filling up with industrious farmers; then it strikes the Arkansas River, and follows up the valley of that stream for several hundred miles, passing over the smooth but narrow bottom, where there is but little wood. The soil, however, is fair and can generally be cultivated without irrigation. On leaving the Arkansas River, the track passes an arid and mountainous section, striking the Rio Grande at Albuquerque, New Mexico, and turns down that stream to El Paso, where it unites with the Texas roads.

These three roads, from Deming, New Mexico, pass over the Southern Pacific Railroad to Los Angeles, California, 715 miles, nearly all of which is over an arid undulating prairie region, with but little wood, water, or grass, until arriving at the Gila River, a small stream that sometimes dries up in summer, but whose narrow borders can generally be made productive by taking water from the river in ditches. Following this stream to its mouth, the road crosses the Colorado River at Yuma, Arizona, and then over the desert and mountains to Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Another road connects with the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe road at Albuquerque, called the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, which runs almost due west, crossing the Colorado River at the Needles and uniting with the Southern Pacific at Mohave, 815 miles from its eastern terminus. The eastern portion of this road, over which I have passed, traverses the most parched, barren, and worthless section of the universe it has ever been my fate to encounter. There are, however, a few insignificant patches of land along the narrow borders of some diminutive watercourses that can be tilled by artificial irrigation.

The Union Pacific Railroad, leaving the Missouri River at Omaha, traverses the left bank of the Platte River for 250 miles over remarkably smooth and level bottomlands from ten to twenty miles wide, which sustain a dense coating of native grass, affording the occupants an unlimited supply of hay. The soil, although somewhat sandy, is generally fertile and tilled without irrigation. There is no wood upon this part of the Platte River, save a scanty fringe of cottonwood, which makes it necessary for the settlers to burn coal, a heavy tax upon them. These conditions continue- until the road crosses the North Platte and bears to the right up Lodge Pole Creek, and thence onward to Salt Lake, and over the Central Pacific Railway to Carson River a distance of about 1,500 miles, through elevated plains, with no wood excepting pine and cedar in the adjacent mountains, and with but little water outside Salt Lake Valley that is available for irrigation.

Only a minute fraction of this vast area is arable, yet it affords a short grass of the buffalo variety, with here and there some bunch-grass, both highly nutritious and stock-raising to a considerable extent, has been started upon the most favorable localities throughout that section of the country. Several towns and hamlets have been established near railway stations along this arid section, the most important of which, Cheyenne and Laramie, are beautifully located and well-built.

The Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, extending from Pueblo, Colorado, to Salt Lake City (650 miles), is one of the most signal achievements in engineering skills ever attempted. This road meanders through a country covered by lofty mountains, with narrow valleys and precipitous canons intervening, one of the latter, the Black Canyon of the Arkansas River, being 2,000 feet deep, through which the Arkansas River rushes with tremendous velocity over precipitous falls and rapids, and the railroad in its tortuous zigzag course through this wonderful gorge doubles upon itself in numerous short curves directed to all points of the compass, so that the locomotive that invariably precedes the passenger train to clear the track occasionally appears to be thousands of feet directly overhead or underfoot, rendering it difficult to realize the fact that it is upon the same track with the observer. The gradient here is 213 feet to the mile, and at one point, 10,857 feet above the sea has attained the highest altitude reached by any railway in America.

The scenery is marvelously grand and picturesque upon this road and its branches. Water and grass are abundant throughout this section, and the mountains abound in pine, cedar, and cottonwood. But the altitude of the valleys is so great here, and the summers so short that grain will not mature with any certainty.

This part of the country will not, therefore, be likely to attract farmers, but cattle-raisers have commenced driving their herds to this section, and stock-growing has for some years past proved remunerative along the branches of the Gunnison and Uncompahgre Rivers as well as in the adjacent Wahsatch Mountains.

The Northern Pacific Railroad from its eastern terminus at Duluth to Portland, Oregon, is 1889 miles in length. This road, for the first 120 miles, traverses a flat, wet, and sandy pine and tamarack region totally destitute of agricultural requirements to the crossing of the Mississippi River at Brainerd. From there, the character of the country contiguous to the road becomes more attractive. The wet sandy soil disappears and is replaced by fertile glades and prairies, interspersed with groves of hard timber, and is abundantly watered with beautiful lakes and small streams, which characteristics continue to Fargo, a thriving city upon Red River of the North, where the St. Paul branch unites with the main trunk road.

From Fargo, North Dakota, the Red River is navigable for steamers to Lake Winnipeg. Below Fargo, the river finds its narrow, deep, and tortuous channel through bottomlands more level, expanded, and fertile than I have seen upon any other watercourse. This vast prairie bottom is from twenty to 75 miles wide, with a dark soil three feet deep, naturally sustaining a dense coating of luxuriant grass, and with the favorable climatic conditions of this locality, it yields without irrigation large crops of the highest grades of spring wheat, only requiring about three months from planting to maturity, as the products of several great plantations in that section have already illustrated.

The railroad from Fargo continues on over a fertile wheat-growing district that is rapidly filling up with substantial farms as far as Bismarck, North Dakota, where it crosses the Missouri River and enters a more sterile region, following the valley of the Yellowstone 600 miles into Montana, where grain can seldom be raised without irrigation, except in some of the sheltered valleys like the Gallatin. Yet the seasons are so short here that frost occasionally injures the crops before they are matured, so flour is sometimes brought here from Minnesota at considerable expense. I am persuaded that Montana is better adapted to stock-raising than any of the more southerly territories for the reason that the nutritious bunch grass, which germinates early in the spring, matures rapidly, and cures like hay before the autumn rainfall washes out its nutritive properties, grows more dense and abundant upon the mountains and valleys in this territory than I have seen it elsewhere.

The snow rarely falls very deep here and is seldom rained upon and frozen so as to form a crust that prevents animals from reaching the grass, as sometimes occurs in Colorado, Wyoming, and other more southern localities. Besides, the winds generally blow off the dry snow from the mountain slopes, exposing the grass, and the herds, as if by instinct, seem to anticipate such contingencies and continue to graze in the valleys until the snow becomes too deep, reserving the mountain pasturage for midwinter consumption. Cattle are said to be remarkably healthy and thrifty in this climate, requiring no other forage but the native grass year-round.

From Helena, the railroad crosses the great continental divide through a pass about 6000 feet above tidewater and runs into northern Idaho along the banks of Clarkes Fork of the Columbia River for 300 miles, and thence down the Columbia River, through Oregon to Portland, which is one of the most beautiful and prosperous new cities I have ever visited, and from its numerous railway and water communications, and its preeminent natural position and resources, it seems destined to become the most important commercial metropolis in the Northwest.

By Randolph Barnes Marcy, 1888. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

About the Author: Randolph Barnes Marcy (1812-1887) was a United States Army officer and Western explorer. On December 12, 1878, he was promoted to the regular rank of brigadier general and was named inspector general of the army. Ramblings In the West appeared in Harper’s Magazine, Volume 76, Issue 453, in February 1888.

Also See:

Tales & Trails of the American Frontier

Westward Expansion & Manifest Destiny

Historical Accounts of American History