Spanish Explorers:

Captain Juan Bautista de Anza II (1736-1788)

Dominguez–Escalante Expedition (1776)

Tristan de Luna y Arellano (1519-1571)

Captain Pedro Menendez de Aviles (1519-1574)

Lucas Vazquez de Ayllon (1475-1526)

Vasco Nunez de Balboa (1475?-1519)

Andres Dorantes de Carranza (1500?-1550s)

Sebastiao Melendez Rodriguez Cermeno (1560?-1602)

Christopher Columbus (1451-1506)

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado.

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado (1510-1554)

Diego de Vargas (1643–1704)

Estevanico (1500?-1539)

Juan de Fuca (15??-1602)

Father Francisco Tomas Garces (1738-1781)

Father Eusebio Francisco Kino (1645-1711)

Juan Ponce de Leon (1460?-1521)

Panfilo de Narvaez (1478?-1528)

Fray Marcos de Niza (1495?-1558)

Juan de Onate (1550?-1626)

Captain Alonso Alvarez de Pineda (1494-1520)

Hernando de Soto (1500-1542)

Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca (1490?-1558?)

“Gold is a treasure, and he who possesses it does all he wishes to in this world and succeeds in helping souls into paradise. “

— Christopher Columbus

Between 1513, when Juan Ponce de Leon first set foot in Florida, and 1821, when Mexico gained her independence, as well as the Spanish possessions in the present United States, Spain left an indelible influence — especially in the trans-Mississippi West, which the United States began to acquire in 1803. Spain was the leading European power in the early imperial rivalry for control of North America and, for centuries, dominated the Southeastern and Southwestern parts of what was later the United States — particularly the States of Florida, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California.

Spain held Louisiana territory between 1762 and 1803 and was mainly content to foster the settlements founded by France rather than initiate new ones. She temporarily lost Florida in 1763 but regained it in 1783. Her possessions reached their maximum extent between 1783 and 1803 when they ranged in a crescent from Florida to California.

Except in California, Spain colonized less fruitful regions than England and France. Yet, she tenaciously clung to them long after she had lost her dominance in Europe, some years after the English defeated her armada in 1588. Frustrated in their search for gold and precious metals, the Spaniards were usually forced to try to wrest a living from the barren soil of an inhospitable land by farming and ranching. Finding native labor much scarcer in the present United States than in her possessions to the south, Spain was forced to spread her colonial empire dangerously thin. A small number of soldiers, settlers, and friars controlled the native masses and, through their labors, obtained what wealth was to be had.

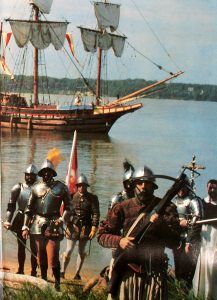

Spain’s motives for colonization were to locate mineral wealth, convert the Indians to Christianity, and counter French and English efforts. The Spanish colonization system was highly successful. First, an armed force subdued the natives and established forts, or presidios, for future protection. Then, zealous missionaries moved in to convert the Indians to the religion of Spain and teach them the arts of civilization. Finally, representatives of the King founded civil settlements in conjunction with the presidios and missions. The Crown controlled the highly centralized process through a bureaucracy that burgeoned as the empire expanded. But, the story begins in the first years of the 16th century when Spain realized that Christopher Columbus had discovered not island outposts of Cathay but a New World!

In the two decades after the first voyage of Columbus, Spanish navigators only began to realize the nature and extent of his remarkable find. The presence of a continental landmass was surmised but not known. Columbus himself had sailed around Puerto Rico, charted most of the West Indies’ shores, touched on the shores of South America, but, without realizing that it was a continent, and mapped the Central American coast from Panama nearly to southern Yucatan.

On his first voyage, late in 1492, he established the colony of Navidad on Hispaniola. However, finding it destroyed on his second voyage, he founded Isabella in January 1494. Isabella failed within two years, and the colonists established Santo Domingo, the first permanent European settlement in the New World.

In 1508-1509, while Juan Ponce de Leon was occupying Puerto Rico and subduing its natives, Vicente Pinzón explored the southern Yucatan coast, and Sebastian de Ocampo circumnavigated the island of Cuba. In 1510, the Spaniards occupied Jamaica and, the following year, Cuba. In 1513, Vasco Nunez de Balboa, who dominated a struggling colony in present-day Colombia, hacked a trail across the Isthmus of Panama and discovered the Pacific Ocean. In 1522, one of the five vessels of the Ferdinand Magellan expedition completed the first circumnavigation of the globe. The lure of adventure and discovery whetted the Spanish desire to explore.

Juan Ponce de Leon was the first Spaniard to touch the shores of the present United States. As Columbus had not remotely realized the extent of his momentous discovery, de Leon never dreamed that his “island” of Florida was a peninsular extension of the vast North American Continent. After coming to the New World with Columbus in 1493, he led the occupation of Puerto Rico in 1508 and governed it from 1509 to 1512. In 1509, he started a colony at Caparra, which was later abandoned in favor of San Juan. He was one of the first of the adelantados — men who “advanced” the Spanish Empire by conquest, the subjugation of the Indians, and the establishment of a quasi-military government.

In 1513, the aging King Ferdinand awarded de Leona a patent to conquer and govern the Bimini Islands in the Bahamas, which the Spaniards had heard but had not yet seen. According to a persistent legend, de Leon would find the marvelous spring whose waters would restore lost youth and vigor. So many wonders had the Spaniards already encountered in the Western Hemisphere that only a cynic would have doubted the existence of such a spring.

Alonso Alvarez de Pineda.

By the time de Leon haplessly attempted to exercise his patent rights to the “island” of Florida in 1521, many geographers and navigators realized that Florida was likely the giant arm of a continent. Two expeditions, one in 1519 by Captain Alonso Alvarez de Pineda and another in 1521 by Francisco Gordillo, indicated this was true.

The Pineda expedition inspired Francisco de Garay, Governor of Jamaica. He placed four vessels under the command of Pineda. He ordered him to find a water passage around or through the landmass whose existence had been indicated by a series of Spanish explorations from 1515 to 18. Captain Alonso Alvarez de Pineda circled west and south around the coast from Florida to Vera Cruz. He named the land off his starboard bow “Amichel”; he called what was probably the Mississippi River “Rio del Espíritu Santo”; and he recommended a settlement at the mouth of the “Rio de las Palmas” — possibly the Rio Grande. Most importantly, he gained substantial knowledge of the unbroken coastline and revealed that a vast continental landmass lay west of Spain’s island headquarters in the Caribbean.

Lucas Vazquez de Ayllon, a prominent magistrate in Hispaniola, in 1521 sent out Captain Francisco Gordillo to sail northward through the Bahamas and strike the continent’s shore, following part of de Leon’s route and trying to round the “island” of Florida from the east. Up the coast, he tacked, extending de Leon’s exploration at least 3° northward and landing on the shores of present South Carolina. Ignoring orders, he loaded his ship with innocent, friendly natives and put about for Hispaniola. He planned to sell his cargo into slavery to replace the significant losses of natives during the first years of the Spanish conquest.

Spanish Conquistadors.

Lucas Vazquez de Ayllon reprimanded him and released the unfortunate captives, but he listened greedily to the report about the fair land to the north. Rushing to Spain, he obtained a patent to colonize the region. A reconnaissance expedition in 1525, led by Pedro de Quexos, extended De Ayllón’s knowledge of the coast as far as present Virginia. The following year, after extensive preparation, Lucas Vazquez de Ayllon set out with three vessels, more than 500 colonists, three padres, and ample supplies and livestock to establish a lasting settlement on the Atlantic shore. He failed. Attempting to settle at an unknown site, possibly in present-day North Carolina, he shifted about 100 miles to the south. He founded a crude settlement named San Miguel de Guadalupe in South Carolina. He died of a fever before the year was out, and internal dissension turned the settlement into anarchy. Less than a third of the colonists survived to return to Hispaniola.

The previous year, a Portuguese navigator named Stephen Gomez, also flying the Spanish flag, completed the exploration of the Atlantic coast by sailing from Newfoundland south to the Florida peninsula in search of the Northwest Passage. The continental block extended from Newfoundland to Tierra del Fuego. Intrepid Spanish explorers were forced off their ships and onto the land if they wished to make additional discoveries, as had Vasco Nunez de Balboa and Cortes before them.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2025.

Also See:

Missions & Presidios of the United States

San Antonio Missions National Historic Park

See Sources.