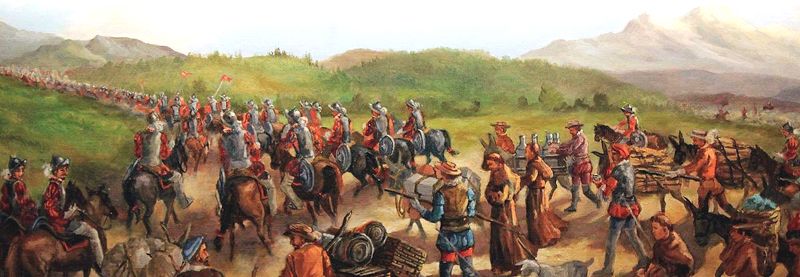

Francisco Vazquez de Coronado, Captain-General of the expedition that bear’s his name, was part of a much larger force. Huge numbers of slaves, Aztec/Mexica allies, servants, herders, tailors, cobblers, cooks, European soldiers, journeymen, and many others came rumbling into northern Mexico’s indigenous villages American Southwest, and the plains of the Midwest.

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado y Luján was born to a noble family in Salamanca, Spain, in 1510. At age 25, he traveled with Antonio de Mendoza’s entourage, the new Viceroy of New Spain in present-day Mexico. He married 12-year-old Beatriz de Estrada there, and the couple would eventually have eight children. Dona Beatiz was the daughter of colonial treasurer and governor Alonso de Estrada, and through her, Coronado inherited a large portion of a Mexican estate. By 1538, he had become the governor of Nueva Galicia, a province of New Spain located northwest of Mexico.

Despite his great fortune and status in Mexico, Coronado wanted to follow in the footsteps of other Spanish conquistadores, such as Hernán Cortés, who conquered the Aztec empire, and Francisco Pizarro González, who conquered the Incas.

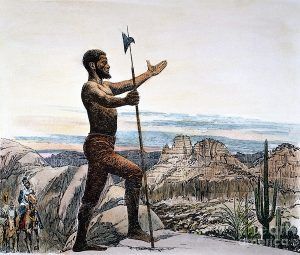

In 1539, he dispatched Friar Marcos de Niza and Estevanico, a survivor of the Narváez expedition, on an expedition north from Compostela toward present-day New Mexico. During this trip, Estevanico was killed by Zuni Indians. When de Niza returned, he told of a city that appeared as wealthy and large as Mexico City, standing high upon a hill. Believing this to be the rumored “Seven Cities of Gold,” later referred to as Cíbola, Viceroy Mendoza began assembling an expedition to conquer and claim the civilization for Spain.

Mendoza soon commissioned Coronado to command the expedition to Cíbola, and both men invested large sums of their own money in the venture. Coronado pawned his wife’s estates for 70,000 pesos. Departing on February 23, 1540, the large expedition left Compostela on Mexico’s west coast en route to the fabled golden cities. The expedition was assembled with two components. One carrying the bulk of the supplies was sent north via the Guadalupe River under Hernando de Alarcón. The other group traveled by land along the trail on which Friar Marcos de Niza had followed.

Leading the land expedition, Coronado headed about 400 Spanish soldiers, 1,300-2,000 Mexican Indian allies, four Franciscan monks, including Friar Marcos de Niza, several slaves, servants, and many family members.

In July, the expedition encountered a group of Zuni Indians in New Mexico, with whom they clashed, and Coronado took over their village. He soon split off parts of his group, sending them in different directions, searching for the elusive Cibola. Pedro de Tovar led one group to the Colorado Plateau, while Garcia López de Cárdenas and his men became the first Europeans to see the Grand Canyon.

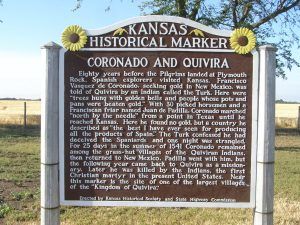

Kansas marker giving a brief history of Coronado’s travels to the area in 1541 located along US Hwy 56 west of Lyons, Kansas.

Coronado spent the winter in Tiguex (tee-wish), a community made of several Pueblo Indian villages along the Rio Grande. His people began to clash with the natives resulting in the Tiguex War. The expedition moved on in the spring of 1841, heading east over the Pecos River. Along the way, they met an Indian man the Spanish called “the Turk,” who told them that he had heard of a wealthy civilization called Quivira far to the east. The Turk led them out of New Mexico to Kansas through Texas and Oklahoma. After reaching the location of Quivira, the Spaniards camped alongside a Wichita Indian village for 25 days. Finding no gold, they killed the Turk in a fury. (See Coronado Expedition)

The expedition then returned south and once again wintered in the Tiguex Province in New Mexico. In about March 1542, Coronado was severely injured in a fall from his horse. After he recovered, he decided the expedition would return to Mexico.

The expedition was ultimately deemed a failure. Vázquez de Coronado, his dreams of fame and fortune shattered and forced into bankruptcy, was publicly scorned and discredited. However, he resumed his position of governor of Nueva Galicia, a position he retained until 1544.

He and his captains were subsequently called in to account for their actions during the quest, including indigenous peoples’ maltreatment. Charges of war crimes were brought against him and his field master, Garcia Lopez de Cárdenas. Coronado was cleared, but Cárdenas was later convicted in Spain because of his role in the brutal Tiguex War.

Ten years after his return, at the age of 42, Coronado died in the relative obscurity of infectious disease on September 22, 1554. He was buried under the altar of the Church of Santo Domingo in Mexico City.

He could not know that the expedition he had led would set the stage for the saga of the American and Mexican West. Native American religions would shift, sometimes forcibly, to incorporate the Franciscan and Jesuit priests’ teachings who would follow the expedition. Furthermore, he and his expeditionaries brought back knowledge of the land and people of the north and opened a way for later Spanish explorers and missionaries to colonize the Southwest.

Coronado National Memorial in Arizona commemorates the Coronado Expedition of 1540-1542 and its lasting impacts on the culture of northwest Mexico and the southwestern United States.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated January 2023.

Also See:

The Mythical Seven Cities of Cíbola

Sources: