“The people who were the icons of the civil rights movement were raised by the people who survived Red Summer.”

— Saje Mathieu, history professor at the University of Minnesota

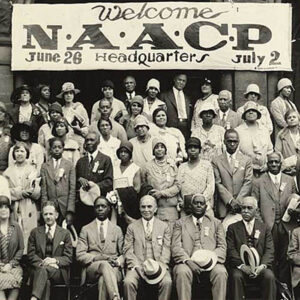

In 1919, Red Summer was a pattern of white-on-black violence that occurred in more than three dozen cities across the United States and in one rural county in Arkansas. The term “Red Summer” was coined by civil rights activist and author James Weldon Johnson, who had been employed as a field secretary by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) since 1916. It was branded “Red Summer” because of the bloodshed that occurred during the worst white-on-black violence in U.S. history.

It flowed in small towns like Elaine, Arkansas, in medium-sized places such as Annapolis, Maryland, Syracuse, New York, and big cities like Washington, D.C., and Chicago, Illinois. Hundreds of African American men, women, and children were burned alive, shot, hanged, or beaten to death by white mobs. Thousands saw their homes and businesses burned to the ground and were driven out, many never to return.

This period of African American history began with the collapse of Reconstruction in 1877. During this period, the political and legal gains won by African Americans during Reconstruction were dismantled, mainly by denying their voting rights and legalizing racial segregation, most notably in the 1896 U.S. Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson, which made racial segregation legal until the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas and the desegregation of the U.S. military after World War II.

The early 20th century witnessed hundreds of thousands of African Americans migrating from the South to the Northeast, Midwest, and West. One of the leading causes for this mass migration was the continuing racial violence, including lynching and racial massacres that targeted Southern black people, as well as the return of the Ku Klux Klan. In addition to those suffering these political and legal injustices, thousands of black people were hanged, burned to death, shot to death, tortured, mutilated, and castrated by white mobs who were rarely prosecuted for their crimes. One of the leaders in the fight against lynching was Ida B. Wells-Barnett, editor of the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight and author of two anti-lynching texts, Southern Horrors and The Red Record.

In 1909, Wells and other civil rights activists, including W.E.B. DuBois and Mary Church Terrell, formed the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which fought lynching, segregation, and other forms of racial injustice.

With the mobilization of troops for World War I and with immigration from Europe cut off, the industrial cities of the American Northeast and Midwest experienced severe labor shortages. As a result, northern manufacturers recruited throughout the South, from which an exodus of workers ensued. World War I intensified the Great Migration, the mass emigration of African Americans from the rural South to the industrial North and Midwest in hopes of escaping the poverty and discrimination of Jim Crow laws.

In the summer of 1917, violent racial riots against blacks due to labor tensions broke out in East St. Louis, Illinois, and Houston, Texas.

Following the war, rapid demobilization of the military without a plan for absorbing veterans into the job market and the removal of price controls led to unemployment and inflation that increased competition for jobs. Jobs were tough for African Americans to get in the South due to racism and segregation.

Many returning servicemen resented that their vacated jobs had been taken, particularly by African Americans. Black laborers already suffered from a negative reputation in the White working community for their use as low-wage-earning strikebreakers, or “scabs,” who would keep factories in operation while the employees went on strike. The situation was worsened in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1917. Many officials and others, with little or no evidence, suspected Black workers of being pawns of Bolsheviks and anarchists.

By 1919, an estimated 500,000 African Americans had emigrated from the Southern United States in the first wave of the Great Migration (which continued until 1940). In many cases, northern Whites — many of them newly arrived immigrants themselves — did not welcome Black newcomers. African American workers filled new positions in expanding industries, such as the railroads and many existing jobs formerly held by whites. These acts increased resentment against blacks among many working-class whites, immigrants, and first-generation Americans.

The anti-black riots developed from a variety of post-World War I social tensions, generally related to the demobilization of both black and white members of the United States Armed Forces following World War I, an economic slump, and increased competition in the job and housing markets between ethnic European Americans and African Americans.

The riots and killings were extensively documented by the press, which, along with the federal government, feared socialist and communist influence on the black civil rights movement of the time. They also feared foreign anarchists, who had bombed the homes and businesses of prominent figures and government leaders.

“The return of the Negro soldier to civil life is one of the most delicate and difficult questions confronting the Nation, north and south.”

— Dr. George Edmund Haynes, an educator employed as director of Negro Economics for the U.S. Department of Labor, 2019

On April 14, 1919, the first race riot occurred in Carswell Grove near Millen, Georgia, where six people, including two white officers and four Black men, were killed at a local Black church. A white mob burned the Carswell Grove Baptist Church down. One newspaper article pointed the finger at a Black man named Joe Ruffin, while other evidence pointed to local white bootleggers and corrupt cops.

In late April of 1919, two Black brothers, Roger and Samuel Courtney, were hunted down by a mob of hundreds of their fellow University of Maine students, led back to campus with nooses around their necks, and forced to tar and feather each other’s naked bodies. No arrests were made, and the incident was kept from local press and university histories. While the exact date of the incident is unknown, it happened on or around April 26.

On May 2, after Benny Richards, a Black farmer, killed his ex-wife and wounded his sister-in-law, a posse of hundreds of citizens and bloodhounds chased him down rather than let the police and legal system decide his fate.

An increase in lynchings and mob violence against Black Americans motivated NAACP leaders like John R. Shillady, James Weldon Johnson, and Walter White to organize the National Conference on Lynching on May 5-6, 1919, in Carnegie Hall, New York City, The goal of the conference was to pressure Congress to pass the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill. It was a project of the new NAACP, which released a report, Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889-1918, in April. The bill faced pushback from Southern politicians who filibustered to prevent the bill from passing in 1922.

“By the God of Heaven, we are cowards and jackasses if, now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land.”

— W.E.B. Du Bois, an official of the NAACP and editor of its monthly magazine

An increase of southern Blacks in northern cities during the first wave of the Great Migration caused competition between the races for jobs and housing. In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a riot occurred over housing on May 10, 2019, as reported here by the Negro Associated Press.

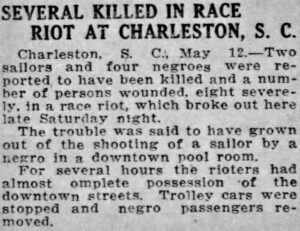

On the same day, riots in Charleston, South Carolina, were spurred by two additional triggers common in violence that summer — booze and military men. Over 1,000 white sailors went on a drunken, violent rampage throughout the city, attacking black citizens and businesses and looting stores. The Charleston riot resulted in the injury of five white and 18 black men, along with the death of three others: Isaac Doctor, William Brown, and James Talbot, all black. Following the riot, the city of Charleston imposed martial law. A Naval investigation found that four U.S. sailors and one civilian — all white men — initiated the riot.

On May 15, 1919, a minor riot between Black and white soldiers occurred in the Presidio in San Francisco after a dispute about a Thai soldier who was moved from the “colored quarters” to the white military housing. Despite defending our country, housing for Black soldiers was not only segregated but often inferior. Black soldiers also faced increased attacks and other forms of discrimination upon returning home.

On the same day, 1,000 white rioters broke Lloyd Clay out of jail, hung him, and burned him in the city center as a crowd watched in Vicksburg, Mississippi. Rumors of an attack on white women spurred the riot.

That month, following the first serious racial incidents, W.E.B. Du Bois, an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and civil rights activist, published his essay Returning Soldiers:

“We Return from the slavery of Uniform, which the world’s Madness Demanded us to don, to the freedom of civil garb. We stand again to look America squarely in the face and call a spade a spade. We sing: This country of ours, despite all its better souls have done and dreamed, is yet a shameful land.… We return. We return from fighting. We return fighting.”

While several riots that summer were related to the perceived need to protect white women against Black men, in Milan, Georgia, the case was reversed. On May 24, 1919, a man named Berry Washington was trying to protect Black teen girls in his neighborhood from white sexual predators and killed one of the men in the process. He was broken out of jail and lynched by a mob of 75-100 men led by the local Baptist minister. Mobs of white citizens continued the violence, destroying Black homes and businesses. A letter to the editor from John Shillady mentioned a lack of newspaper coverage of the gruesome events common throughout the Red Summer.

On May 29, 1919, a race riot involving sailors of both races in New London, Connecticut, was said to have spread into nearby New Haven later that night, although the second riot did not appear to be race-related. The riots were between members of the military.

A white woman named Ruth Meeks accused a black man named John Hartfield of attacking and raping her on June 9, 1919, in Ellisville, Mississippi. Hartfield ran for his life, but white mobs eventually shot and captured him on June 2. They then took him to a doctor to heal his wound. On June 26, the mob took Hartfield to a field, cut off his fingers, hung him from a tree branch, and shot him over 2,000 times; and when the rope was severed, and Hartfield fell from the tree, the mob burned his body. After he was killed, some 10,000 whites came to witness the corpse while vendors sold trinkets and photographs.

On June 28, a riot that began between black and white servicemen spread to communities throughout Annapolis, Maryland. It was started because of some perceived threat against women.

In early July, a white race riot in Longview, Texas, led to the deaths of at least four men and destroyed the African American housing district in the town.

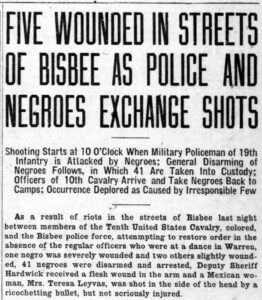

On July 3, 1919, members of the U.S. Army segregated the 10th Cavalry Regiment, whose African American troops were referred to as “Buffalo Soldiers,” who were in Bisbee, Arizona, to participate in the town’s July 4th parade and celebration of Black soldiers’ contributions to the recently ended war in Bisbee, Arizona. When a fight broke out between a white policeman and members of the regiment, it turned into a drunken riot between soldiers, police, and locals of both races. While most records point the finger at a white military policeman as the instigator of the riot and not the Buffalo Soldiers, other articles blamed the local Industrial Workers of the World’s involvement. At that time, Bisbee was already a ticking time bomb of racial and labor tensions long before the events that summer. At least eight people were seriously injured, and 50 soldiers were arrested. This incident was unusual for being between police and military. Most other riots during the Red Summer of 1919 involved wide-scale white rioting against blacks, both sides civilians.

On July 6, a man named Eli Cooper was lynched in the vicinity of Dublin, Georgia, for being a rumored ringleader among Black activists. A mob shot him 50 times, threw his body in a church, and lit it on fire. The mob then made its way throughout town, burning Black owned churches and lodges. Locals raised money for a reward for capturing the culprits and for rebuilding the churches.

On July 11, L. Jones, an African American schoolteacher in Longview, Texas, was beaten to death for publishing an anonymous article in the Chicago Defender about a lynching that occurred in Longview. The man lynched was rumored to be having an affair with a white woman.

On July 14, the Garfield Park riot took place in Garfield Park, Indianapolis, Indiana, where multiple people, including a seven-year-old girl, were wounded when gunfire broke out.

On July 15, 1919, a minor incident happened on an integrated streetcar in Port Arthur, Texas. Like many other industrial cities that summer, tensions were already high due to labor strikes.

Beginning on July 19, Washington, D.C., had four days of mob violence against black individuals and businesses perpetrated by white men — many of them in the military and in uniforms of all three services–in response to the rumored arrest of a black man for rape of a white woman. Off-duty sailors and recently discharged Army veterans led the mobs, who attacked local Black neighborhoods and assaulted random African American individuals on the streets. The men rioted, randomly beat black people on the street, and pulled others off streetcars for attacks. On July 21, in Norfolk, Virginia, a white mob attacked a homecoming celebration for African American veterans of World War I. At least six people were shot, and the local police called in Marines and Navy personnel to restore order. On the same date, riots in Washington, D.C., began as retaliation over Black soldiers being attacked by whites the night before. Clusters formed throughout the city, including on Pennsylvania Avenue near the White House.

When the overwhelmed police refused to intervene, the black population fought back, arming themselves with bats, clubs, pistols, and knives. Soon, Black mobs were attacking white passersby just as indiscriminately as Whites did to Blacks. The city closed saloons and theaters to discourage assemblies. Meanwhile, the four white-owned local papers, including the Washington Post, “ginned up…weeks of hysteria”, fanning the violence with incendiary headlines, calling in at least one instance for a mobilization of a “clean-up” operation. After four days of police inaction, President Woodrow Wilson mobilized the National Guard to restore order. When the violence ended, a total of 15 people had died — ten white people, including two police officers, and five black people. Fifty people were seriously wounded, and another 100 less severely wounded. It is one of the few times in 20th-century white-on-black riots that white fatalities outnumbered those of black people.

“They had caught a Negro and deliberately held him as one would a beef for slaughter, and when they had conveniently adjusted him for lynching, they shot him… I heard him groaning in his struggle as I hurried away as fast as I could without running, expecting every moment to be lynched myself.”

— Carter G. Woodson, the historian who founded Black History Month in 1926. Woodson narrowly escaped harm by hiding in the shadows as a white mob approached.

The NAACP sent a telegram of protest to President Woodrow Wilson:

“The shame put upon the country by the mobs, including United States soldiers, sailors, and marines, which have assaulted innocent and unoffending negroes in the national capital. Men in uniform have attacked negroes on the streets and pulled them from streetcars to beat them. Crowds are reported …to have directed attacks against any passing negro… The effect of such riots in the national capital upon race antagonism will be to increase bitterness and danger of outbreaks elsewhere. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People calls upon you as President and Commander in Chief of the nation’s Armed Forces to make a statement condemning mob violence and to enforce such military law as the situation demands…”

A riot in New York City on July 20 stemmed from an argument between a white man and a Black man over the war. After shots were fired, a crowd formed, eventually growing to over 1,000 people, according to reports. However, no significant injuries were reported.

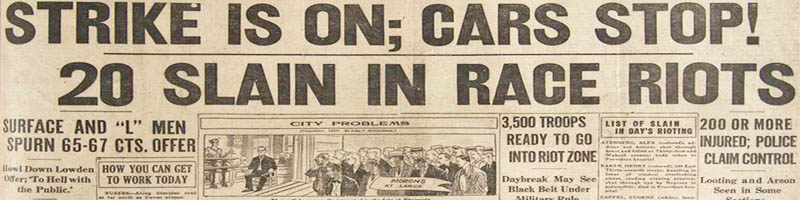

Beginning on July 27, the massive Chicago race riot marked the greatest massacre of Red Summer. Chicago’s beaches along Lake Michigan were segregated by custom. When Eugene Williams, a black youth, swam into an area on the South Side customarily used by whites, he was stoned and drowned. Chicago police refused to take action against the attackers, and young black men responded with violence. With racial tensions already high as competition for jobs and housing heightened, the riot spread to clusters throughout Chicago, lasting for 13 days, with the white mobs led by the ethnic Irish.

White mobs destroyed hundreds of primarily black homes and businesses on the South Side of Chicago. The State of Illinois called in a militia force of seven regiments, several thousand men, to restore order. The riots resulted in casualties that included 38 fatalities, including 23 blacks and 15 whites; 527 were injured, and 1,000 black families were left homeless. Other accounts reported that 50 people were killed, with unofficial numbers and rumors reporting even more. Numerous investigative reports were organized about Chicago’s riots.

“The truth is there ain’t no Negro problem any more than there’s an Irish problem or a Russian or a Polish or a Jewish or any other problem. There is only the human problem. All we demand is an open door. You give us that, and we won’t ask nothin’ more of you.”

– Union member, The Chicago Race Riots

On July 28, 1919, a recently returned Black soldier, the son of a local preacher, was arrested in Newberry, South Carolina, for insulting a young white girl. Other reports said he wrote her a love letter. After it was discovered he was carrying photos of white women in his pockets, a mob attempted to break him out of jail to lynch him, but law enforcement had moved him earlier for safety.

On July 29, with labor strikes and riots occurring at factories, stockyards, and mills throughout the U.S., the Industrial Workers of the World, anarchists, and ‘reds’ were often mentioned in the press as instigators behind the troubles between the races. While many people assume that this is where the term ‘Red Summer’ derived, James Weldon Johnson used the term regarding the bloodshed.

On July 31, 1919, tensions during a labor strike led to a small race riot in Syracuse, New York, between Black strikebreakers and white steelworkers.

In August of 1919, in Jacksonville, Florida, several black taxi drivers were killed by white passengers, resulting in black taxi drivers refusing service to white riders. When one white rider was denied service, he fired into a crowd of black people, killing one man. Police wrongly blamed Bowman Cook and John Morine for the man’s death. Three weeks later, on September 8, a mob broke into the jail where the men were being held and captured them. The mob drove them to a desolate area of town and shot them, then tied Cook’s body to a car and drove it for 50 blocks.

On August 5, an incident in Lexington, Nebraska, resulted in the forced expulsion of all Black residents from the town.

On August 12, at its annual convention, the Northeastern Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs denounced the rioting and burning of Negroes’ homes, asking President Woodrow Wilson “to use every means within your power to stop the rioting in Chicago and the propaganda used to incite such.”

On August 18, 1919, a riot began between the races at Prairie Pebble Phosphate Company in Mulberry, Florida. Troops were called in after a baby and two others were injured.

On August 26, a Black man named Eli Cooper was kidnapped from his home near Cadwell, Georgia, shot over 50 times, and his body set afire in his church. A handful of lynchings that summer occurred in the victim’s churches, and cases of arson of Black churches and businesses were on the rise.

On August 30, after a manhunt, a white mob of over 1,000 men dragged Black soldier Lucius McCarty around Bogalusa, Louisiana, behind a car and then lynched him on the lawn of the woman he was said to have assaulted.

The Knoxville Riot in Tennessee started on August 30-31 after the arrest of a black suspect named Maurice Mays on suspicion of murdering a white woman named Bertie Lindsey. A mob destroyed the jail, searching for Mays to lynch him, freeing 16 white prisoners in the process, including suspected murderers. The mob attacked the African American business district, where they fought against the district’s black business owners, leaving at least seven dead and more than 20 wounded. Mays, who had been taken to safety before the riot, was later sent to death by the electric chair despite mounting evidence he was likely innocent. It was one of the largest riots that summer.

At the end of August, the NAACP protested again at the White House, noting the attack on the organization’s secretary in Austin, Texas, the previous week. Their telegram read: “The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People respectfully enquires how long the Federal Government under your administration intends to tolerate anarchy in the United States?”

In response to the Red Summer, the African Blood Brotherhood formed in northern cities in September 1919 to serve as an “armed resistance” movement. Protests and appeals to the federal government continued for weeks.

On September 8, 1919, a white mob seeking justice over an attack on a white girl broke two prisoners in Jacksonville, Florida, out of jail. The men were not the original criminals sought, but instead, just two Black men in the wrong place at the wrong time. The mob riddled them with bullets, dragged their bodies behind a car, and lynched them in front of a crowd.

In the autumn of 1919, following the violence-filled summer, George Edmund Haynes reported on the events as a prelude to an investigation by the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary. He identified 38 separate racial riots against blacks in widely scattered cities in which whites attacked black people. Unlike earlier racial riots against blacks in U.S. history, the 1919 events were among the first in which black people in number resisted white attacks and fought back. A. Philip Randolph, a civil rights activist and leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, publicly defended the right of black people to self-defense.

September 21, a Black man named Ephram Gethers was shot by an off-duty police officer after Gethers smashed the man’s straw hat in New York City. Straw hat smashing was a common activity after September 15, the unofficial day wearing straw hats was deemed socially unacceptable. It was meant to be a playful act and developed a carnival atmosphere, wherein permission to be a little prankish became its tradition. The event that night involved crowds of primarily white people smashing hats.

From September 28-29, the race riot of Omaha, Nebraska, erupted after a mob of over 10,000 ethnic whites from South Omaha attacked and burned the county courthouse to force the release of a black prisoner accused of raping a white woman. The mob lynched the suspect, Willie Brown, hanging him on a street post and burning his body. as hundreds of men, women, and children watched. After scraps of skin and clothing were taken from the body, other souvenirs of the lynching were sold to spectators, with photo books of the events later sold as memorabilia. Brown was not the only person the mob turned against. Omaha’s mayor, Edward Parsons Smith, had a noose put around his neck and was hung when trying to stop Willie Brown’s lynching. He was quickly cut down by police before his death but remained hospitalized in serious condition for days.

The group then spread out, attacking black neighborhoods and stores on the north side, destroying property valued at more than a million dollars. Once the mayor and governor appealed for help, the federal government sent U.S. Army troops from nearby forts, commanded by Major General Leonard Wood, a friend of Theodore Roosevelt and a leading candidate for the Republican nomination for president in 1920.

On September 30, in the short span of 12 hours, three different Black men were lynched by large, white mobs in Montgomery, Alabama. In one case, after a shootout with police, a white mob broke a Black prisoner out of the infirmary and shot him repeatedly before setting his body on fire inside one of the hospital’s wards.

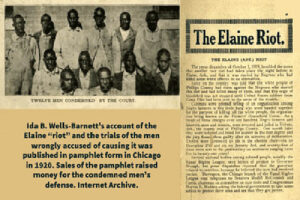

On the same date, Black sharecroppers holding a union meeting near Elaine, Arkansas, were ambushed by gunfire. Planters opposed such efforts to organize and thus tried to disrupt their meetings in the local chapter of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America. The sharecroppers began fighting back, which, combined with the union organization, was seen as an ‘uprising.’ The planters formed a militia to arrest the African American farmers, and hundreds of whites came from the region. They acted as a mob, attacking black people over two days at random. All Black residents in town were rounded up and had their weapons confiscated, leaving them defenseless. People were indiscriminately gunned down in the streets based on their skin color.

Like Omaha, Washington, D.C., and Chicago, troops were called in to restore peace, although many ended up contributing to the bloodshed. Governor Charles Brough ordered 500 Army soldiers from nearby Camp Pike to march on Elaine and put down what was labeled an “insurrection” among the Black sharecroppers.

During the riot, the mob killed an estimated 100 to 237 black people, while five whites also died in the violence, earning the event the nickname of the “Elaine Massacre.” Following the bloodshed, local white landowners, lawmen, and business leaders known as “The Committee of Seven” posted a handbill throughout town urging Black residents to keep quiet and return to work as if nothing happened. Elaine was considered the most deadly event of the Red Summer.

The committee concluded that the Sharecroppers’ Union was a Socialist enterprise and “established for the purpose of banding negroes together for the killing of white people.” The report generated such headlines as the following in the Dallas Morning News: “Negroes Seized in Arkansas Riots Confess to Widespread Plot; Planned Massacre of Whites Today.” Several Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation agents spent a week interviewing participants, though speaking to no sharecroppers. The Bureau also reviewed documents, filing a total of nine reports stating there was no evidence of a conspiracy of the sharecroppers to murder anyone.

The local government tried 79 black people, who were all convicted by all-white juries, and 12 were sentenced to death for murder. As Arkansas and other southern states had disenfranchised most black people at the turn of the 20th century, they could not vote, run for political office, or serve on juries. The remainder of the defendants were sentenced to prison terms of up to 21 years. Appeals of the convictions of six of the defendants went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which reversed the verdicts due to the failure of the court to provide due process. The decision was a precedent for heightened Federal oversight of defendants’ rights in the conduct of state criminal cases.

Estimates vary as to how many African Americans were killed, but upwards of 200 are believed to have lost their lives.

“They knocked her (Lula Black) down, beat her over the head with their pistols, kicked her all over the body, almost killed her, then took her to jail… The same mob went to Frank Hall’s house and killed Frances Hall, a crazy old woman housekeeper, tied her clothes over her head, threw her body in the public road where it lay thus exposed till the soldiers came Thursday evening and took it up.”

— Ida B. Wells, a pioneering black journalist, in The Arkansas Race Riot.

On October 3, a riot in Baltimore, Maryland, was started by white Navy bluejackets against an entire Black neighborhood and was quickly quelled by police.

On October 4, there was a union strike at Gary’s U.S. Steel Mill in Gary, Indiana. This strike was held by the white labor population of the mill as the union could not recruit the black workers’ support. U.S. Steel hired almost 1,000 local and non-local black strikebreakers to break this strike. These strikebreakers were shipped into Gary for their safety, and cots, entertainment, and overtime pay were provided. At the same time, U.S. Steel turned to theatrics and attempted to agitate the white strikers. They did this by first emasculating white strikers and then later by paying unrelated black residents of Gary to march in a parade toward the steel mill. Hundreds of striking workers assaulted a stalled streetcar bearing 40 black strikebreakers. At first, the mob resorted to heckling, then the throwing of rocks, and eventually, the mob dragged the strikebreakers from their streetcar and beat them, dragging them through the streets. The hysteria led to an eight-block mob, leaving many unconscious in its wake, leading to the state militia and federal troops stepping in to intervene. Martial law was enacted, and many historians agree that the Riot of 1919 broke the unions in Gary.

On October 10, a riot began in Hubbard, Ohio, just outside of Youngstown, between Black strikebreakers and Romanian factory workers. A few hundred miles away in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, a similar riot broke out at a steel mill, with the foreign-born workers the ones attacked in that case.

October 16, 1919, a small Georgia newspaper, the Eastman Times-Journal, printed this story about the lynching of Eugene Hamilton next to a story about another lynching in nearby Washington. Especially in the South, lynchings that occurred in rural areas, without the crowds seen in cities, were often barely covered in the press. Actual lynching numbers that summer could be much higher.

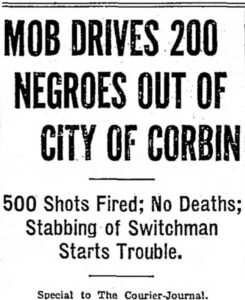

On October 31, the town of Corbin, Kentucky, decided to forcibly remove all of the Black residents in town almost overnight, resulting in violent clashes between the races and one death. Riots throughout the summer were followed by stories of Blacks being forced out of town or fleeing to other nearby cities for safety.

On November 3, Paul Jones, a Black man accused of assaulting a white woman, was taken from police custody and lynched by a mob in Macon, Georgia.

On November 13, in Wilmington, Delaware, after two Black men were accused of killing a white policeman, a white mob of about 300 men went on the hunt to find them. The police intervened and, after overtaking the mob, moved the Black suspects to a jail in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for safe-keeping.

On November 22, tensions had been high all summer in Bogalusa, Louisiana, after a group of white labor union organizers came to town to organize the Black timber workers. Unrelated to the riot earlier in the summer, this riot escalated so quickly that troops were called in for backup. Four union organizers were killed, and the event became known as the Bloody Bogalusa Massacre.

A letter from the National Equal Rights League, dated November 25, appealed to President Woodrow Wilson’s international advocacy for human rights: “We appeal to you to have your country undertake for its racial minority that which you forced Poland and Austria to undertake for their racial minorities.”

November 30, Sam Mosely, an African American man, was found dead, hanging from a tree, in Lake City, Florida, assumed to be dead at the hands of a mob. He was thought to have attacked a white woman.

Researchers believe that in ten months, more than 250 African Americans were killed in at least 25 riots across the U.S. by white mobs that never faced punishment. Historian John Hope Franklin called it “the greatest period of interracial strife the nation has ever witnessed.”

Beyond the lives and family fortunes lost, it had far-reaching repercussions, contributing to generations of black distrust of white authority. But it also galvanized blacks to defend themselves and their neighborhoods with fists and guns; reinvigorated civil rights organizations like the NAACP and led to a new era of activism; gave rise to courageous reporting by black journalists; and influenced the generation of leaders who would take up the fight for racial equality decades later.

Fringe white supremacist terror groups did not initiate the most violent incidents during the Red Summer of 1919. Ordinary white civilians and veterans, unaffiliated with the Ku Klux Klan or any other racist organization, formed most of the mobs. Many of the dozens of incidents that occurred over the years were made far worse because local, state, and federal officials hesitated to take action or turned a blind eye to the violence. Racial violence broke out in some of the nation’s most populous cities.

It’s impossible to say precisely how many people were killed or injured in the race riots and lynchings of the Red Summer of 1919, as official records for some incidents were poor or never documented. However, hundreds of people lost their lives, thousands were injured, and many more were forced to flee their homes.

The NAACP gained about 100,000 members that year. Soon, blacks were going to Congress, pressing congressmen and senators to pass anti-lynching legislation. At the same time, they were fighting back in the courts and filing lawsuits when people were mistreated or railroaded.

The Red Summer enlightened many to the growing racial tension in America. The violence in these major cities prefaced the soon-to-follow Harlem Renaissance, an African American cultural revolution, in the 1920s. Racial violence appeared again in Chicago in the 1940s and in Detroit as well as other cities in the Northeast as racial tensions over housing and employment discrimination grew.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, February 2024.

Also See:

Tulsa, Oklahoma Massacre, 1921

Sources:

History Draft

National Archives

National Park Service

National World War I Museum

Public Broadcasting Service

Wikipedia