Not nearly as well known as the Oregon or Santa Fe Trails, the Old Spanish Trail was a contemporary of these two more famous trails but was primarily a trade route rather than an emigrant trail, as the path was too rough for wagons. Put together with pieces of previous routes utilized by the Indians and explorers, this extension of the Santa Fe Trail from Missouri to New Mexico connected Santa Fe with California, playing a major factor in the development of the southern part of the state.

Approximately 1,120 miles long, it ran through areas of high mountains, arid deserts, and deep canyons through six states, including New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and California. One of the most arduous trade routes ever established in the United States, it was first explored as early as 1776 but would not see extensive pack train use until about 1830.

Juan Maria de Rivera explored the eastern areas of southwest Colorado and southeast Utah in 1765. Franciscan missionaries Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante unsuccessfully attempted the trip to California, which was just being settled, in 1776. However, they only reached the Great Basin in Utah before returning to Santa Fe, New Mexico. More missionary trips followed. Trappers led by Jedediah Smith worked out the middle part of the trail through Nevada and California in about 1827.

The trail was officially blazed in 1829-30 when Santa Fe merchant Antonio Armijo combined the information from previous explorers and led a trading party of 60 men and 100 mules to California.

Armijo avoided the worst of the Mojave Desert, traveling south of Death Valley following intermittent streams and locating new springs to support the party. Though he arrived at San Gabriel Mission in California with his group intact, they were forced to rely on mule meat during their final days on the trail. After trading blankets and other goods, they returned to New Mexico, and Armijo was rewarded by being made the “Commander for the Discovery of the Route to California.”

Word quickly spread about the successful trade expedition, and other traders began making regular trips. Some small-scale emigration and criminal activities also occurred along the trail, including raiding California ranchos for horses and the extensive Indian slave trade. It was the first major thoroughfare across the American Southwest and was described as “the longest, crookedest, most arduous pack mule route in the history of America.” Caravans usually left Santa Fe in the fall, when cooler desert temperatures prevailed, and returned in the spring when new grass was present to feed the large herds of animals being driven eastward. A one-way journey might take from 1 ½ to 3 months.

As numerous traders made the long trek, several main routes and alternates were developed over the years, including a route following the Colorado River to Needles, California, which became the preferred route for many. Others wishing to trade with the Ute Indians followed a route as far north as Salt Lake, known as the “North Branch.”

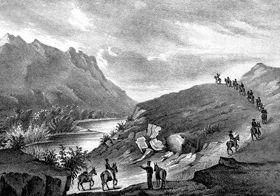

After the route had been used for about 15 years, John C. Fremont, “The Great Pathfinder,” took the route, guided by Kit Carson, in 1844. In his report for the U.S. Topographical Corps, he officially named it the “Old Spanish Trail.” New Mexico-California trade continued until the mid-1850s when a shift to freight wagons and the development of wagon trails made the old pack trail route obsolete.

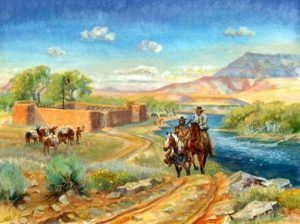

Pack train leaving New Mexico.

The Old Spanish Trail officially lasted until 1848, when the territory it crossed became part of the United States. The Mexican-American War marked the official demise of the trail. Afterward, the western portion of the trail was improved and made passable for wagons. The first passage by a wheeled vehicle was made in 1848 when a party of soldiers from the Mormon Battalion traveled from Los Angeles to the new Mormon capital at Salt Lake City. The road would continue to serve Mormons traveling between California and Utah, at which time, this portion was often referred to as the Mormon or Salt Lake Trail.

Portions of the old route continued to be used by pack traders until the mid-1850s, by which time more improved roads had been blazed, and freight wagons could be used.

Beginning in the 1920s and continuing sporadically through the following decades, various states and associations began to mark portions of the old trail. In 2002, Congress passed the Old Spanish Trail Recognition Act, today known as the Old Spanish National Historic Trail.

The Main Route

Beginning in Santa Fe, this route looped northward through Colorado and Utah to avoid the deep river gorges of the Grand and Glen Canyons on the Colorado River before descending across western Utah to Las Vegas, Nevada. The trail crossed the Mohave Desert before reaching the San Gabriel Mission near Los Angeles. The difficult route crossed two deserts and was often littered with the bones of horses and mules that had died of thirst. Trips were made only in the winter when water was more likely to be found in the desert regions.

Traders traveled up the Rio Grande Valley from Santa Fe before heading northwest through northern New Mexico, crossing the Continental Divide, and traveling to the San Juan River in Colorado. The route continued across Colorado, passing near Mesa Verde and entering Utah east of Monticello.

The trail then proceeded north through difficult terrain to Spanish Valley near today’s Moab, Utah. Those historic traders were amazed as they passed through the terrain near what are now Canyonlands and Arches National Parks before making their way across the Colorado and Green Rivers to the southern part of the Great Basin and Mountain Meadows.

From there, they crossed the northwestern corner of Arizona before continuing to the artesian springs of Las Vegas, a significant watering hole, where they would rest before heading off across the dry Mohave Desert, stopping at Mountain Springs, Nevada, before crossing into California and making stops at Resting Springs, Salt Springs, and Bitter Springs, each about a day’s travel apart, and sometimes dry. They then went to the only intermittently dependable water source, the Mojave River. If parts of the Mojave River were dry, travelers could sometimes find water by digging in the old river bed. They then followed the river to a point near Cajon Pass over the San Bernardino Mountains. Descending Cajon Pass to reach the coastal plains, the trail turned west along the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains to the Mission San Gabriel. This was a supply point for early travelers and the destination for the first trade caravan led by Antonio Armijo in 1829. However, for later traders, they continued to what was then a small plaza in the sleepy little town of Los Angeles, about nine more miles along the trail.

Alternate routes for this journey existed through central Colorado and northwest Arizona.

Armijo Route

The original 1829 Armijo Route took a more direct path across northern Arizona and southern Utah, passing near present-day Monument Valley, Navajo National Monument, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, and Pipe Spring National Monument.

From there, they crossed the northwestern corner of Arizona before continuing to the artesian springs of Las Vegas, a significant watering hole, where they would rest before heading off across the dry Mohave Desert, stopping at Mountain Springs, Nevada, before crossing into California and making stops at Resting Springs, Salt Springs, and Bitter Springs, each about a day’s travel apart, and sometimes dry. They then went to the only intermittently dependable water source, the Mojave River. If parts of the Mojave River were dry, travelers could sometimes find water by digging in the old river bed. They then followed the river to a point near Cajon Pass over the San Bernardino Mountains. Descending Cajon Pass to reach the coastal plains, the trail turned west along the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains to the Mission San Gabriel. This was a supply point for early travelers and the destination for the first trade caravan led by Antonio Armijo in 1829. However, for later traders, they continued to what was then a small plaza in the sleepy little town of Los Angeles, about nine more miles along the trail.

Alternate routes for this journey existed through central Colorado and northwest Arizona.

North Branch

The North Branch of the trail traveled from Santa Fe northeastward to Taos, New Mexico, and into Colorado near Great Sand Dunes National Park. From there, the trail crossed the Continental Divide and the Gunnison National Forest.

Although few traces of the early traders’ trail remain, the Trail is commemorated with numerous historical markers in the states it crossed.

More Information:

Old Spanish Trail Association

P.O. Box 11189

Pueblo, Colorado 81001

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2023.

Also See:

Struggle For Possession of the West – The First Emigrants